Current Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

By 2050, 200 Million People Will Be<br />

Displaced Because Of Climate Change.<br />

their only choice will be to stay on the island and ride out<br />

the storm. Once the storm arrives, the road out of the<br />

island will be flooded.<br />

“It takes a lot of prayer to live down here,” Theresa<br />

Handon, Chris Brunet’s sister, said. “I think, ‘Please God,<br />

no more storms,’ but I know it’s going to come.”<br />

With every storm that hits the island comes a chance<br />

that another home will be destroyed. Louisiana contains 40<br />

percent of the nation’s wetlands, but each year an amount<br />

of land larger than the size of Manhattan is sapped from<br />

the state’s coastline. The water has now overtaken many<br />

structures that were once a part of the community. Sea<br />

level rise, shifting soils, and several hurricanes have led to<br />

the abandonment and eventual demise of what once were<br />

people’s homes.<br />

“Climate change didn’t happen overnight, so we can’t fix<br />

it overnight,” Comardelle said. “What we can do is make<br />

the best of what we’ve been given and adapt.”<br />

Many of the tribal members who remain on the island<br />

despite the rising waters are those who can’t afford any other<br />

option. Most of those who have left the island remain in the<br />

tribe but are spread throughout Louisiana.<br />

“The tribe has physically and culturally been torn apart<br />

with the scattering of members,” the resettlement proposal<br />

submitted to the Department of Housing and Urban<br />

Development’s National Disaster Resilience Competition<br />

states. “A new settlement offers an opportunity for the tribe to<br />

rebuild their homes and secure their culture on safe ground.”<br />

“We know we aren’t the only ones,” Comardelle says. “If we<br />

can do this, not only for our people, but to be a beacon of hope<br />

for other communities is important. This is not just about us.”<br />

The resettlement proposal argues that Isle de Jean Charles<br />

“is ideally positioned to develop and test resettlement adaptive<br />

methodologies,” something that is badly needed around the<br />

world. As such, the plan aims to move families to a historically<br />

contextual and culturally appropriate community.<br />

As hurricane season looms, the tribe hopes to be spared<br />

long enough to have time for relocation; however, with<br />

questions from the state about how to allocate the money,<br />

the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw culture hangs in the balance.<br />

“To stay here would have been my first choice, but common<br />

sense tells me that if I don’t take advantage now and a<br />

hurricane comes and destroys everything, then where will I<br />

go?” said the Reverend Roch Naquin, a resident who grew up<br />

on the island and was a trapper until going to seminary school.<br />

“This is not just about resettling the community on the island,”<br />

Comardelle said. “It’s reuniting the community that is left.”<br />

Having already lost so much of their land and their tribal<br />

heritage to the water, relocation is not just crucial for their<br />

personal safety but also for the longevity of their culture<br />

and traditions.<br />

“At one time, water was our life and now it’s almost our<br />

enemy because it is driving us out, but it still gives us life,”<br />

Comardelle said. “It’s a double-edged sword. It’s our life and<br />

our death.” Story and Photos by Carolyn Van Houten<br />

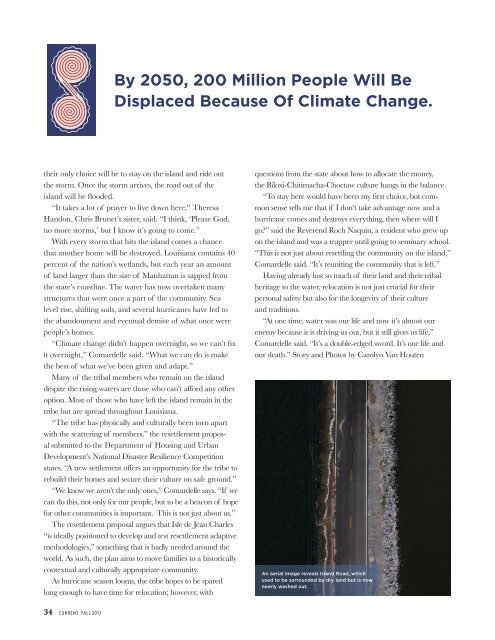

An aerial image reveals Island Road, which<br />

used to be surrounded by dry land but is now<br />

nearly washed out.<br />

34 CURRENT FALL 2017