Global families

Managing risks around cycles and supercycles Global Investor, 01/2007

Managing risks around cycles and supercycles

Global Investor, 01/2007

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

GLOBAL INVESTOR 1.07 Basics — 23<br />

time ever, regulatory approval for that kind of diagnostic again was<br />

no small feat. It was a real accomplishment for the company.<br />

So, with your chip technology, let’s say you find a particular<br />

gene that looks interesting for a particular disease, but then there<br />

has been a professor or a group of people working in the field<br />

for years. Would you then collaborate? Do you do academic collaboration<br />

when you find new biomarkers?<br />

Prof. Lindpaintner: The pharmaceutical industry lives and dies by<br />

academic collaborations. There’s no two ways about it. We are completely<br />

dependent on excellent relationships with academia for each<br />

and every one of our clinical development studies and not only in<br />

the clinical field, but also of course in the basic science field. So<br />

this is very much a networking and partnering with both academicians<br />

and small biotechnology companies.<br />

Can you give any examples of a successful academic collaboration<br />

and successful biomarker from which you have been able<br />

to develop specific drugs for specific groups of people? Are there<br />

any successful tailor-made drugs on the market today?<br />

Prof. Lindpaintner: Yes, indeed. Herceptin is a monoclonal antibody<br />

that is revolutionizing the treatment of breast cancer. This is a<br />

drug where the story started in academia with the recognition that<br />

some tumors behave differently than others. In other words, they’re<br />

much more aggressive, they’re much more likely to kill their carriers<br />

in a short period of time. Based on that, basic research demonstrated<br />

that the majority of those very aggressive tumors have one characteristic<br />

in common, and that is an overexpression, in other words<br />

an exaggerated level, of a particular gene called Her 2, an oncogene,<br />

or cancer-related gene. The gene product of Her 2 is a receptor on the<br />

cell surface which binds a specific growth factor and signals the cell<br />

to grow and divide. Now, the next leap of faith was then to say, well<br />

what if we develop a drug that very specifically inhibits that particular<br />

mechanism; it should help the patients in whom this mechanism<br />

contributes to rapid tumor growth. And this was a time when it had<br />

just recently become possible to actually produce specifically targeting<br />

antibodies.<br />

These are mouse monoclonals?<br />

Prof. Lindpaintner: Yes. The next step was to actually make the<br />

mouse monoclonal antibody into a “humanized” antibody, and then<br />

clinical research over years was done demonstrating every step<br />

along the way, that yes, this seems to work, yes this seems to be<br />

promising, yes this is actually something that is a completely new<br />

approach to treating cancers. This is not only a particularly effective<br />

therapy because it specifically addresses the mechanism by which<br />

these cancer cells grow, but also – and this is just as important for<br />

these patients who in the past have had to endure the ravages of<br />

conventional chemotherapy – it is a much better-tolerated form of<br />

therapy. It is a kind of silver bullet, a heat-seeking missile that hones<br />

in on just those cells that overexpress the oncogene. And it doesn’t<br />

do collateral damage. This is a good example for a personalized,<br />

targeted therapy. So this is a therapy that is specifically targeted to<br />

those women – about 25% of all breast cancer patients – who have<br />

the overexpression of Her 2 and the aggressive type of tumor. It’s<br />

not tailored for each individual, but for a group of patients who now<br />

benefit from a better treatment.<br />

So you don’t believe in an individual drug? You don’t see this<br />

as a trend that could evolve in the future, where each person has<br />

their own personalized drug?<br />

Prof. Lindpaintner: If you consider that it costs USD 1 billion to<br />

develop one new medicine, and if we work to develop that specific<br />

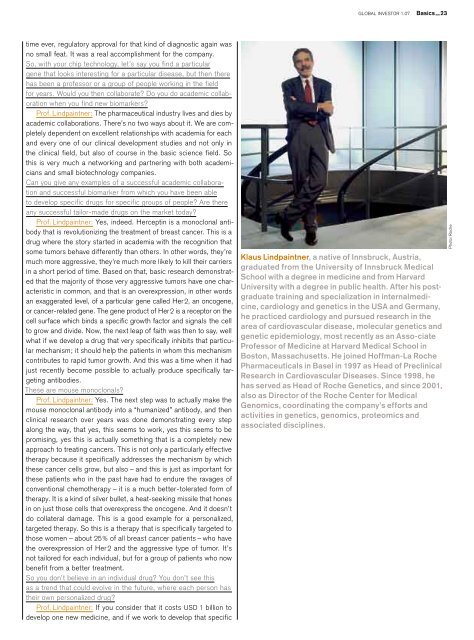

Klaus Lindpaintner, a native of Innsbruck, Austria,<br />

graduated from the University of Innsbruck Medical<br />

School with a degree in medicine and from Harvard<br />

University with a degree in public health. After his postgraduate<br />

training and specialization in internalmedicine,<br />

cardiology and genetics in the USA and Germany,<br />

he practiced cardiology and pursued research in the<br />

area of cardiovascular disease, molecular genetics and<br />

genetic epidemiology, most recently as an Asso-ciate<br />

Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School in<br />

Boston, Massachusetts. He joined Hoffman-La Roche<br />

Pharmaceuticals in Basel in 1997 as Head of Preclinical<br />

Research in Cardiovascular Diseases. Since 1998, he<br />

has served as Head of Roche Genetics, and since 2001,<br />

also as Director of the Roche Center for Medical<br />

Genomics, coordinating the company’s efforts and<br />

activities in genetics, genomics, proteomics and<br />

associated disciplines.<br />

Photo: Roche