Microfinance

Global Investor Focus, 02/20065 Credit Suisse

Global Investor Focus, 02/20065

Credit Suisse

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

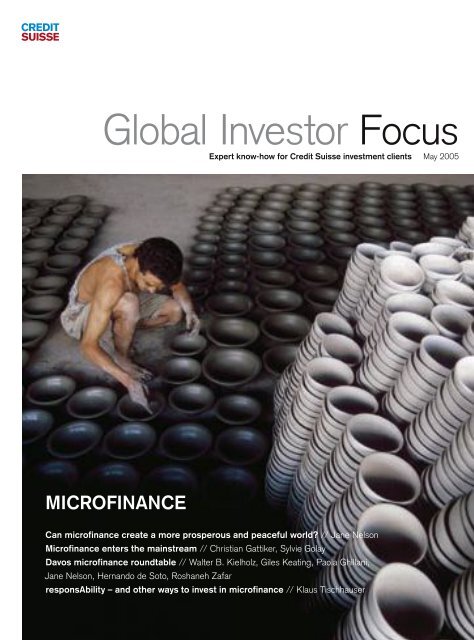

Global Investor Focus<br />

Expert know-how for Credit Suisse investment clients May 2005<br />

MICROFINANCE<br />

Can microfinance create a more prosperous and peaceful world? // Jane Nelson<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> enters the mainstream // Christian Gattiker, Sylvie Golay<br />

Davos microfinance roundtable // Walter B. Kielholz, Giles Keating, Paola Ghillani,<br />

Jane Nelson, Hernando de Soto, Roshaneh Zafar<br />

responsAbility – and other ways to invest in microfinance // Klaus Tischhauser

A daily<br />

interest rate of<br />

20%:<br />

For every five pesos borrowed in the morning,<br />

six must be repaid by the evening –<br />

these are standard conditions set by<br />

loan sharks<br />

in the Philippines.<br />

Source: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) website

500 m<br />

450 m<br />

400 m<br />

350 m<br />

300 m<br />

250 m<br />

200 m<br />

150 m<br />

100 m<br />

50 m<br />

There are an estimated 500 million microentrepreneurs worldwide, but less than 10% of them<br />

have access to financial services.<br />

CMore information on page 8

How can USD 100 change an economy? // One<br />

small loan can change a family, but several<br />

can strengthen a community, and thousands could<br />

transform an entire economy. //<br />

CMore information on page 9

Write-off rates of less than 2% for properly managed microfinance lending portfolios compare favorably to many<br />

traditional commercial bank portfolios.<br />

Microcredit<br />

98% of microloans are promptly repaid – with interest.<br />

CMore information on page 16

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—06<br />

Editorial<br />

The United Nations Organization has declared this year as the International<br />

Year of Microcredit 2005. The objective of the initiative is to<br />

make a noticeable contribution to reducing poverty over the next ten<br />

years. Numerous loans of small sums of money should help the poor<br />

to help themselves.<br />

This idea was already successfully applied in the nineteenth century,<br />

when Europe stood on the threshold between an agricultural and<br />

industrial society. The notion of microcredit emerged out of consideration<br />

for opening the door for small and microbusinesses to gain<br />

access to capital in order to free themselves from poverty. The success<br />

of this concept in Europe inspires confidence that herein lies one<br />

of the keys to broadly underpinned economic growth in the emergingmarket<br />

countries. The wealth of entrepreneurial imagination and the<br />

ideas that people create in these countries – as well as the energy<br />

that they expend to realize these ideas under adverse conditions – are<br />

quite impressive, in our view. The resoluteness with which these individuals<br />

work to enhance their standard of living can also be perceived<br />

in their high level of morality, guiding them to promptly repay these<br />

microloans – with interest.<br />

The conservatively estimated demand for microcredit exceeds the<br />

total amount of development aid provided by the Western world. Hence,<br />

sustained development can only be achieved through private investment<br />

in a sound economic system. Public-sector development aid is a prerequisite<br />

for building up such a system, of which functioning microfinance<br />

institutions and clearly regulated ownership rights are a part.<br />

Among our wealthy clients, there is an increasing number of<br />

investors who would like to invest some of their money in self-help<br />

projects. These clients have an affinity for enterprising people in thirdworld<br />

countries and feel the need to return something to society,<br />

making a valuable contribution to bridge the great divide between rich<br />

and poor.<br />

Credit Suisse, together with partner banks, has founded the company<br />

“responsAbility” and set up the corresponding responsAbility<br />

Global <strong>Microfinance</strong> Fund to try and fulfill the needs of its clients in<br />

this regard, thereby providing the requisite funding for microcredit.<br />

Additional important details surrounding the microfinance theme<br />

are available for investors in this debut issue of Global Investor<br />

Focus – the first of a series that will in the future provide investors<br />

with in-depth analysis of important longer-term investment themes.<br />

Dr. Arthur Vayloyan<br />

Member of the Executive Board of Credit Suisse Group<br />

Head of Private Banking Switzerland

p Glossary<br />

Bankable are those individuals or businesses deemed eligible to<br />

obtain financial services that can lead to income generation,<br />

repayment of loans, savings and build-up of assets.<br />

Group lending, also known as solidarity lending, is a mechanism<br />

that allows a number of individuals to provide collateral or<br />

guarantee a loan through a group repayment pledge. The<br />

incentive to repay is based on peer pressure: if one person in<br />

the group defaults, the other group members make up the<br />

payment amount.<br />

Individual lending, focuses on one client. The lending institution<br />

may ask for collateral or a guarantor.<br />

Microcredit is a small amount of money loaned to a client by a<br />

bank or other institution. Microcredit can be offered to an<br />

individual, or through group lending or community lending.<br />

Microentrepreneurs are people who own small-scale businesses,<br />

which are known as microentreprises. These businesses are<br />

usually family owned and operated. Typical microentrepreneurial<br />

activities include retail kiosks, sewing workshops, carpentry<br />

shops and market stalls.<br />

Microsavings are deposit services that allow people to store<br />

small amounts of money for future use, often without minimum<br />

balance requirements. Savings accounts allow households to<br />

save small amounts of money to meet unexpected expenses<br />

and plan for future investments such as education and old age.<br />

Some microfinance institutions require forced savings as an<br />

indicator for credit worthiness.

p Reference sources<br />

International Year of Microcredit 2005<br />

www.yearofmicrocredit.org<br />

Consultative Group to assist the poor<br />

www.cgap.org<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> Gateway<br />

www.microfinancegateway.org<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> Information eXchange (MIX) Market<br />

www.mixmarket.org<br />

The Virtual Library on Microcredit<br />

www.gdrc.org/icm<br />

Journal of <strong>Microfinance</strong><br />

http://marriottschool.byu.edu/microfinance/<br />

p Investment Community<br />

ACCION<br />

www.accion.org<br />

Oikocredit<br />

www.oikocredit.org<br />

Triodos Bank<br />

www.triodos.com<br />

BlueOrchard Finance<br />

www.blueorchard.ch<br />

responsAbility<br />

www.responsability.ch<br />

p Rating agencies<br />

Microrate<br />

www.microrate.com<br />

Planet Rating<br />

www.planetrating.org<br />

p Leading <strong>Microfinance</strong> Institutions and Networks<br />

ACCION<br />

www.accion.org<br />

Compartamos<br />

www.compartamos.com<br />

FINCA International<br />

www.villagebanking.org<br />

ProCredit Holding<br />

www.procredit-holding.com<br />

Women’s World Banking<br />

www.swwb.org

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—07<br />

08<br />

Jane Nelson // Harvard University<br />

Harnessing the potential of microfinance<br />

Especially in developing countries, microenterprises lack access to<br />

reliable financial services, but the solutions are in our reach.<br />

Table of contents<br />

12<br />

Klaus Tischhauser // responsAbility<br />

Ecuador: The market, credit systems and clients<br />

One of the key success factors is the way the banking business<br />

has adapted to clients’ needs. A closer look at Ecuador.<br />

15<br />

Sylvie Golay, Ursula Oser // Credit Suisse<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> as an attractive business model<br />

Enhancing the productivity of millions of microentrepreneurs in the<br />

emerging markets can be financially rewarding.<br />

18<br />

Davos roundtable<br />

Is access to capital a key factor for development?<br />

Is access to capital a key factor for development and poverty alleviation?<br />

The role of microfinance.<br />

28<br />

Christian Gattiker-Ericsson, Sylvie Golay // Credit Suisse<br />

The microfinance market<br />

An increasing number of mainstream financial players are becoming<br />

active in the promising market for microfinance.<br />

30<br />

Philipp Jung // University of St. Gallen, Mike Imam // Credit Suisse<br />

Securitization of microloans<br />

Refinancing microfinance banks has the potential to generate significant<br />

benefits for both investors and microfinance banks.<br />

32<br />

Klaus Tischhauser // responsAbility<br />

Bridging the gap: The responsAbility Global <strong>Microfinance</strong> Fund<br />

Institutional and private investors’ access to financial returns and<br />

social benefits.<br />

34<br />

36<br />

Author index<br />

Imprint

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—08<br />

How to give 500 million microentrepreneurs access to financial services // In<br />

the world’s most successful economies, small and microenterprises serve as a major<br />

engine of job creation and economic growth. However, those operating in developing<br />

countries often lack access to reliable financial services. This does not have to be<br />

the case. We have the solutions within our reach – and they include the creation of more<br />

inclusive financial markets that profitably serve these needs.<br />

Jane Nelson / Harvard University<br />

Harnessing the potential<br />

of microfinance<br />

One of the greatest economic and moral imperatives of our time is to<br />

develop innovative new funding mechanisms, technologies and business<br />

models that can empower small and microenterprises by providing<br />

them with reliable and commercially viable financial services and<br />

other business support. Expanding access to such services creates<br />

an unprecedented opportunity to unleash the spirit of innovation and<br />

entrepreneurship, as well as the untapped human capital and financial<br />

assets that already exist in millions of low-income households and<br />

communities all over the world.<br />

The renowned economist Hernando de Soto, for example, estimates<br />

that “the total value of the real estate held but not legally owned by<br />

the poor of the Third World and former communist nations is at least<br />

USD 9.3 trillion.” 1 Management strategist C.K. Prahalad speaks of the<br />

huge market potential of the four to five billion underserved people<br />

who live at the bottom of the world’s economic pyramid on less than<br />

USD 2 a day; people who are willing and able to pay for products and<br />

services that are affordable, accessible and available. 2 There are an<br />

estimated 500 million microentrepreneurs worldwide and less than<br />

10% of them have access to financial services, other than through the<br />

usurious rates of informal-sector moneylenders. In addition to ensuring<br />

better governance and institutions, which is primarily the role of government,<br />

the crucial challenge for corporate leaders, bankers and investors<br />

is to develop new financing mechanisms, technologies and business<br />

models that can serve these untapped markets in a manner that is<br />

profitable and sustainable.<br />

Successful track records<br />

In the case of microfinance – loans, savings, insurance, transfer services<br />

and other financial products targeted at low-income clients 3 – we<br />

already have successful examples that work. There are a growing number<br />

of microfinance institutions (MFIs) that serve as effective and increasingly<br />

profitable intermediaries between individual microenterprises and<br />

a range of commercial banks, development banks, donor agencies, nonprofit<br />

organizations, and socially responsible and commercial investors.<br />

Some of these MFIs have track records spanning more than ten years,<br />

with quantifiable results that show not only consistently high repayment<br />

of loans on time, but also clear economic and social benefits to<br />

the microentrepreneurs, their families, their communities and their

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—09<br />

countries (please refer to page 12 for some case studies in Ecuador).<br />

There is growing political will to support the expansion of these MFIs,<br />

building on models that already work and experimenting with new<br />

approaches. Individual and institutional investors can also play a crucial<br />

leadership role, both on a for-profit basis – looking for a competitive<br />

financial return – and on a social investment or philanthropic<br />

basis. In doing so, they can be part of an emerging global agenda that<br />

has the potential to expand economic opportunity, alleviate poverty<br />

and transform the prospects of poor communities around the world.<br />

Access to microfinance can make all the difference<br />

As UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan has observed, “A small loan, a<br />

savings account, an affordable way to send a paycheck home, can<br />

make all the difference to a poor or low-income family. With access<br />

to microfinance, they can earn more, build up assets and better protect<br />

themselves against unexpected setbacks and losses. They can<br />

move beyond day-to-day survival toward planning for the future. They<br />

can invest in better nutrition, housing, health and education for their<br />

children. <strong>Microfinance</strong> is a way to extend the same rights and services<br />

to low-income households that are available to everyone else.<br />

It is recognition that poor people are the solution, not the problem. It is<br />

a way to build on their ideas, energy and vision. It is a way to grow<br />

productive enterprises and thus allow communities to prosper. Where<br />

businesses cannot develop, countries cannot flourish.” 4<br />

How can individual investors play a role?<br />

There are at least five ways that individual investors can support the<br />

global expansion of microfinance:<br />

p First, they can invest in microfinance funds, such as the respons-<br />

Ability Global <strong>Microfinance</strong> Fund, which provide loans to microfinance<br />

institutions (MFIs), make equity investments in these institutions,<br />

and/or securitize their assets. There is growing evidence that such<br />

funds can provide investors with a reasonable financial return while<br />

also generating significant social benefits.<br />

p Second, depending on their risk profile, investors can choose to<br />

invest directly in microfinance institutions, especially some of the<br />

larger and more established institutions that operate on a global or<br />

national basis, by buying securitizations of microloans, bonds or equity<br />

stakes.<br />

p Third, they can make grants or philanthropic donations to microfinance<br />

institutions, nonprofit development organizations or academic<br />

institutes to support education, training, research and other activities<br />

that will help to expand microfinance.<br />

p Fourth, they can financially support and/or get personally involved<br />

in the wide range of workshops, conferences, project visits, research<br />

projects and media activities that are occurring under the umbrella of<br />

the UN International Year of Microcredit 2005.<br />

p Fifth, they can choose to target their investments or philanthropic<br />

support on institutions and initiatives that focus on a particular region<br />

or client group, such as female entrepreneurs or young entrepreneurs.<br />

Entrepreneurs as part of the solution<br />

Many individual investors have an impressive personal record or family<br />

tradition of wealth creation and innovation. What better way to continue<br />

to build private assets, while also leaving a broader public legacy, than<br />

to invest in the next generation of wealth creators and innovators, both<br />

at home and abroad? Many of these will be large companies, but there<br />

is also enormous potential to dedicate a percentage of investment<br />

portfolios and philanthropic donations to building the success of<br />

microfinance and microenterprises. In doing so, investors can effectively<br />

combine economic value creation with societal value creation,<br />

and private gain with public good.<br />

We have the means to alleviate extreme forms of poverty. We have<br />

the financial and technical resources to make a difference. What we<br />

need is the political will and the personal investment choices that will<br />

channel these resources in the right direction. This requires investments<br />

in innovative funding mechanisms, technologies and business models.<br />

It requires willingness to recognize entrepreneurs in low-income communities<br />

as key partners to reach a solution. Above all, it requires<br />

recognition that the spirit of social and economic entrepreneurship –<br />

combined with personal and corporate responsibility, and with good<br />

government – offers one of our greatest hopes for creating a more<br />

prosperous and peaceful world.<br />

æ<br />

1<br />

De Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West<br />

and fails everywhere else. Basic Books, 2000.<br />

2<br />

Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through<br />

Profits. Wharton School Publishing, 2004.<br />

3<br />

United Nations. <strong>Microfinance</strong> and Microcredit: How can USD100 change an Economy?<br />

International Year of Microcredit, 2005. www.yearofmicrocredit.org<br />

4<br />

Speech made by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan at the launch of the International<br />

Year of Microcredit, 18 November 2004.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—10<br />

The global microfinance landscape<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> activities have been emerging in almost every country around the globe. Still, the market<br />

structure may vary a lot. To illustrate the big differences in economic basis, microfinance markets and potential,<br />

this overview shows some examples from every region of the world.<br />

Source: The CIA World Factbook, MIX Market, company data<br />

Region Country Population 2003 GDP Per capita GDP<br />

(millions) (USD billions) (USD)<br />

Central America Mexico 105 941 9,000<br />

South America Peru 28 146 5,100<br />

Middle East /North Africa Egypt 76 295 4,000<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa South Africa 43 457 10,700<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa Kenya 32 33 1,000<br />

Eastern Europe Serbia and Montenegro 11 24 2,200<br />

Central Asia Russia 144 1,282 8,900<br />

Indian subcontinent India 1,065 3,033 2,900<br />

Asia Cambodia 13 25 1,900<br />

1 Definition of poverty line varies from country to country.<br />

2 All data are from MIX Market or company websites and the most up-to-date available.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—11<br />

% of population below poverty line 1 Name of MFI 2 Founded/licensed No. of customers Average microloan<br />

(USD)<br />

40% Compartamos 1990 309,637 294<br />

54% Bantra 1994 245,000 883<br />

17% Banque du Caire (MF Business Unit) 2001 45,000 311<br />

50% Teba Bank 1976/2000 160,000 1,117<br />

50% K-Rep Bank 1984/2000 45,400 456<br />

30% ProCredit Bank Serbia 2001 37,465 6,550<br />

25% KMB Bank 1992 32,178 780<br />

25% BASIX 1996 190,000 165<br />

36% Amret 1996/2000 105,283 77

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—12<br />

A closer look at Ecuador reveals some of the different approaches used in the<br />

field of microfinance.<br />

Klaus Tischhauser ⁄ responsAbility<br />

Ecuador: The market, credit<br />

systems and clients<br />

Ecuador is one of the Andean countries in Latin America that hosts a<br />

diverse microfinance industry made up of banks, non-banking financial<br />

institutions, cooperatives and NGOs. The Superintendencia de Bancos<br />

supervises the entire banking sector, including the regulated microfinance<br />

institutions. In 2004 alone, these institutions posted a volume<br />

growth rate of 174%. With a total of USD 360 million in assets at the<br />

end of 2004, the microfinance industry accounts for just 6% of the<br />

entire financial sector’s USD 6 billion in assets. But the impressive<br />

growth rates indicate that the microfinance sector serves a segment<br />

of the market that is still largely underserved.<br />

The largest Ecuadorian bank, Banco del Pichincha, has now<br />

become a serious player in the country’s microfinance sector. Within<br />

a short period, through a specific microfinance program, the bank has<br />

attained a microfinance market share of close to 15%, which is already<br />

half the microlending volume of the former uncontested dominator<br />

Banco Solidario. In this so-called downscaling process, established<br />

traditional banks reach out to client groups that they had previously<br />

regarded as unbankable. In October 2001, German ProCredit Holding<br />

Group entered the market and opened a specialized microfinance<br />

institution called Sociedad Financiera Ecuatorial (SFE). Since then, the<br />

three players have shared nearly 60% of the Ecuadorian microfinance<br />

market. The good results achieved by the microfinance pioneers have<br />

finally induced mainstream banks to turn their attention to the majority<br />

of the country’s population.<br />

Village banking: The credit system to reach the masses<br />

On Friday, 3 March 2005, 14 women gather in a small grocery store.<br />

Situated on a side street in Ecuador’s capital city of Quito, every other<br />

week the tiny shop serves for an hour or so as a bank. All members<br />

of the group, including the shop owner, Fernando Garcia, are clients<br />

of FINCA Ecuador, an affiliate of the international microfinance network<br />

FINCA International, the pioneer of so-called village banking credit<br />

systems. The group is just one of nearly 2,000 throughout Ecuador,<br />

with a combined total of more than 40,000 clients.<br />

Today is a special day; a credit cycle comes to its end. On this<br />

occasion, the members not only repay the last installment of their<br />

loans (comprising principal, interest and a savings component), but<br />

also dissolve and reinstate their own “village bank.” Supervised,

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—13<br />

trained and supported by their FINCA credit officer, Viviana Cruz, they<br />

elect a president, a vice president, a cashier and an auditor. After a<br />

short round of applause after each election, the necessary documents<br />

are signed and the group starts the banking business. Using computer<br />

output brought along by the credit officer, the cashier starts with<br />

a report about the group’s savings. Then a serious issue is immediately<br />

dealt with: a group member did not show up and has not paid<br />

her last installment. Soon, one of the group’s members leaves the<br />

shop to go and look for her. The group is understandably concerned,<br />

for if the money is lost, the group’s savings will be tapped first to<br />

cover the loss. Then each group member would be held jointly liable.<br />

This solidarity mechanism, coupled with the close contact between<br />

the credit officer and the group, is one of the main secrets behind the<br />

success of village banking credit systems. The group members know<br />

each other well; they normally live and work in the same street, neighborhood<br />

or village. So the ability to run a business successfully and<br />

the honesty and creditworthiness of each new member are assessed<br />

by those who are in the best position to do so.<br />

Discipline as a success factor<br />

After the meeting, the members walk away from the store – not far,<br />

sometimes just across the road – and go back to their businesses.<br />

Like Teresa Rosero, the owner of a small tailor’s shop right across the<br />

street. When asked why she had become a FINCA client, she replied:<br />

“It’s closer and more convenient than where I was before (she was a<br />

client of one of FINCA’s competitors), and I can do business with my<br />

neighbors who I know and trust.” Has she ever had difficulty repaying<br />

her loans? Never in the three years that she has been with FINCA,<br />

she says. Well, recently it has become a bit harder; the economy took<br />

a deeper turn for the worse, so her sales likewise declined. She<br />

therefore wants to be prudent and is postponing her plan to apply for<br />

an increase in her current loan of USD 1,000.<br />

The next group member, Maria Espinoza, runs her tiny business<br />

a few meters down the street. It’s not much more than just a box on<br />

wheels with an umbrella to protect against sun and rain. On top of the<br />

box there is an entire pig on display fresh out of the oven, “hornado”<br />

style (“horno” is the Spanish word for oven). She sells the delicious<br />

meat along with potatoes and herbs. Maria did not participate in<br />

today’s meeting because she had to look after her business, which<br />

was started on a USD 300 loan. Unless they have a good excuse,<br />

members must pay an absence fee for not personally participating in<br />

meetings. Discipline is a success factor not only for the management<br />

of microbusinesses, but also for the management of the village banking<br />

groups. That’s what FINCA’s credit officer told her group when<br />

the members asked to meet just once a month instead of biweekly so<br />

they could spend more time on their businesses. And it is her job to<br />

maintain FINCA’s excellent current credit repayment rate of close to<br />

98%.<br />

Individual lending: The credit system for growing needs<br />

The ProCredit branch Quito Norte attracts quite a crowd. Its bright<br />

and inviting new design chimes with the worldwide rebranding of the<br />

entire ProCredit network consisting of 19 microbanks in Latin America,<br />

eastern Europe and Africa. On the ground floor, a few seats accommodate<br />

new clients who patiently wait until they can move on to the<br />

desks where their personal information is entered or checked. ><br />

Ecuador at a glance<br />

Source: The CIA World Factbook, Institute of International Finance<br />

Capital Quito Currency (adopted in 2000) US dollar<br />

Government type Republic GDP per capita (purchasing power parity, 2003 estimate) USD 3,300<br />

Population (2004 estimate) 13.2 million GDP real growth rate (2003 estimate) 2.5%<br />

Population growth rate (2004 estimate) 1.03% Public debt (in % of GDP, 2003 estimate) 53.7%<br />

Median age (2004 estimate) 23 years Exports (goods, 2004 estimate) USD 6.6 billion<br />

Life expectancy at birth (2004 estimate) 76 years Current-account balance (2004 estimate) USD 125 million<br />

Population below poverty line (2003 estimate) 65% Inflation rate (consumer prices, 2003 estimate) 7.9%<br />

Literacy rate (population over the age of 15, 2003 estimate) 92.5% Unemployment rate 1 (2003 estimate) 9.8%<br />

Natural resources<br />

1<br />

Underemployment of 47% (2003 estimate)<br />

Petroleum, fish, timber,<br />

hydropower<br />

Labor force by occupation<br />

(2001 estimate)<br />

Agriculture (30%), industry<br />

(25%), services (45%)

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—14<br />

Klaus Tischhauser: “It’s amazing to see how much entrepreneurial<br />

energy can be unleashed.”<br />

There are several tellers at the back of the room for cash transactions.<br />

Armed guards at the building entrance and next to the teller windows<br />

provide security for the bank and its clients. The two upper floors are<br />

filled with desks where credit officers interview loan applicants and<br />

analyze clients’ businesses. ProCredit banks use individual lending<br />

as its credit system of choice for micro and small business lending.<br />

The loan decision is not based on collateral, but rather on projected<br />

future cash flows and the ability of the client and the business to<br />

produce them. Although the handsome building and modern equipment<br />

are certainly important in attracting new clients, a key part of<br />

the credit officers’ work takes place outside the premises. To really<br />

get to know and understand a client’s business, a credit officer needs<br />

to spend a lot of time with clients in their own working environment.<br />

That explains the row of motorbikes in front of the bank and the helmet<br />

on each credit officer’s desk.<br />

Viviana Andrango is one of ProCredit’s loan officers for microbusinesses.<br />

Her district is the Atucucho neighborhood on the outskirts of<br />

Table 1<br />

FINCA and ProCredit client base structure<br />

Source: Finca Ecuador, ProCredit Ecuador<br />

Finca<br />

ProCredit<br />

Total clients 42,676 20,760<br />

Village banking groups 1,878 —<br />

Average loan size USD 309 USD 2,098<br />

Total loans outstanding USD 13,179,000 USD 43,555,000<br />

Total client savings USD 2,671,000 USD 6,696,000<br />

On-time repayment rate 97.97% 99.39%<br />

Quito, where unemployed farmers from the countryside illegally settled<br />

some years ago in search of work. At that time, there were only dirt<br />

roads, no electricity and no water system. “I should have taken pictures<br />

back then. Incredible development has taken place here,” says Viviana,<br />

pointing at different shops that have all been her clients for some<br />

years now. She is particularly proud of her first and now biggest client,<br />

a store with a working capital loan of USD 10,000. The shop owner,<br />

César Crespo, started his business in a single-story building. Over<br />

time, his family has invested in additional floors – a visible form of<br />

wealth creation. The added space is being used as storage room, which<br />

allows the shop to purchase in larger quantities at lower prices.<br />

Personal relationships are key<br />

The business run by Gabriela and Sebastián Nieto with an outstanding<br />

loan of USD 800 is more modest. It sells menswear, and the owners<br />

would like to expand. Gabriela and Sebastián would be happy to take<br />

out a loan of USD 1,500, but Viviana argues that this is too big a step<br />

for a business with such seasonal fluctuations.<br />

The longstanding relationship that Viviana has with her clients and<br />

the level of mutual trust are essential for her work and for the individual<br />

lending system in microfinance in general. In many cases,<br />

Viviana is considered part of the extended family and gets invited to<br />

weddings and other such events. The depth of her relationship with<br />

her clients also becomes evident when she’s on holiday. Her clients<br />

would rather wait for her to return than speak to some other credit<br />

officer, a behavior more associated with private banking clients, who<br />

often demand permanent availability of their relationship manager. In<br />

the context of microfinance, this underscores the equally important<br />

roles that personal relationships and mutual trust play in forming the<br />

basis of the business.<br />

æ<br />

Note: The names of the clients mentioned in this article have been changed to protect<br />

their privacy.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—15<br />

How to achieve repayment rates of 98% // The current microfinance industry<br />

could grow into a USD 15–20 billion financial market in the coming years – if the microfinance<br />

industry is able to grasp the market potential. The industry’s profitability,<br />

with double-digit returns on equity as well as default rates below 2%, are encouraging<br />

aspects.<br />

Sylvie Golay, Ursula Oser / Credit Suisse<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> as an attractive<br />

business model<br />

The microfinance industry provides a wide range of financial services<br />

to microenterprises. Microenterprises are small businesses in urban<br />

or rural areas that are generally family owned and operated. They are<br />

active in the trade, service and production sectors, mainly in the socalled<br />

informal economy. It is estimated that there are about 500<br />

million microentrepreneurs in the world, with average microcredit of<br />

around USD 500. These estimates further indicate that today only<br />

10% of these microenterprises have access to reliable financial services.<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> is actually a high-growth industry, fueled not only<br />

by the size of its target market, but also by its profitability. The market<br />

is witnessing growth rates of 20% to 40%, with extensive diversity in<br />

structures and frameworks across the world. Concurrently, microfinance<br />

is maturing into a more transparent and regulated industry. In<br />

recent years, 250–500 commercially viable institutions, serving an<br />

estimated 50 million microentrepreneurs, have emerged from this very<br />

fragmented market place. They increasingly receive attention from<br />

regulators, auditors and ratings agencies. In many countries – e.g.,<br />

Bolivia, Brazil, Peru and El Salvador – new types of financial licenses<br />

that are tailor-made for deposit-taking microfinance institutions have<br />

been introduced.<br />

Different types of risks<br />

Loan portfolio quality is one factor determining a microfinance institution’s<br />

specific risk since it is the basis for future cash flow in the<br />

absence of formal guarantees. Fostering a close relationship and<br />

mutual trust between loan officers and their clients is thus key for any<br />

microfinance institution. Leading institutions provide timely information<br />

on their loan portfolios. They report repayment rates of 98% for<br />

properly managed loans, which compares quite favorably to many<br />

traditional commercial bank portfolios. The payment behavior of microentrepreneurs<br />

is clearly superior to that of US credit card holders, for<br />

example (see Figure 1). <strong>Microfinance</strong> institutions are very solvent<br />

because credit risk is spread over thousands of microcredit borrowers<br />

who mostly have only their business as resource for financial survival.<br />

Importantly, rapid growth has not come at the expense of portfolio<br />

quality given the huge still-unserved client pool. Systematic risk is<br />

mitigated by the low correlation with political and economic conditions<br />

because the informal sector, by its very nature, is less directly linked<br />

to the formal economy.<br />

Institutional investors have standard practices for credit appraisal,<br />

which includes rating of investments. <strong>Microfinance</strong> ratings >

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—16<br />

from specialized ratings agencies – e.g., Micro Rate – help to enhance<br />

investor confidence. The leading microfinance institutions should and<br />

do increasingly search for a risk appraisal by international rating agencies<br />

(S&P, Fitch or Moody’s).<br />

Financial profitability as a prerequisite for global success<br />

In terms of profitability, data compiled by Micro Rate suggest that the<br />

leading microfinance institutions are profitable companies, surpassing<br />

many domestic and international banks. Return on equity (ROE) for<br />

32 Latin American institutions averages 19%. Return on assets (ROA),<br />

another indicator of financial strength, averages 4.8%. At the same<br />

time, the operating expense ratio (operating expense divided by gross<br />

loan portfolio) has dropped to 21%, with the most efficient microfinance<br />

institutions in the region approaching 10%. Operation expense includes<br />

staff as well as administrative expense, making the ratio a measure<br />

of the overall efficiency of the respective microfinance institution.<br />

Since staff is the main cost factor, loan officers’ productivity in dealing<br />

with their clients is key for improving and maintaining efficiency.<br />

Some worry that excessive concern over profitability may compromise<br />

the social and development goals. However, given the everincreasing<br />

funding needs in this rapidly growing business, serving poor<br />

clients can only be secured by financially profitable institutions, which<br />

are able to grow their capital base. Charging unrealistically low interest<br />

rates would prohibit sustainable microlending. Indeed, microfinance<br />

institutions need to charge interest rates that are higher than “normal”<br />

bank rates because the administrative costs of making small loans<br />

are high in relation to the amount lent.<br />

Figure 1<br />

Typical default rate of microfinance loans versus<br />

US credit card business (2002)<br />

Source: Credit Suisse, CSFB European Securitization Research, MIX Market<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

%<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> loans<br />

US credit card business<br />

Lending methodology<br />

Besides the cooperative model, several lending methodologies have<br />

been developed in order to adapt to client’s needs and constraints<br />

(see Table 1, page 17). Solidarity groups are one of them. In this type,<br />

three to ten clients form a group to get access to financial services.<br />

The group members are collectively responsible for the repayment of<br />

the loan. In contrast to the cooperative model, where the profits<br />

remain in the cooperative in the form of equity, or are distributed to<br />

the members, the earnings generated by solidarity groups are used<br />

to build up reserves or group funds. The ownership of these funds is<br />

often unclear.<br />

Village banking, which can be seen as a mix of the two previous<br />

models, has an autonomous structure that allows its members access<br />

to financial services also in remote areas. The village bank is created<br />

via savings or/and membership fees and is managed by a committee<br />

elected by the members. As for solidarity groups, repayment relies on<br />

collective pressure. Analogical to cooperatives, profits are used to<br />

increase equity or distributed to members. In addition to these partly<br />

microfinance-specific lending methodologies, a lot of microfinance<br />

institutions or microbanks, such as BancoSol in Bolivia, rely on traditional<br />

individual lending.<br />

Double-bottom line<br />

Experience has shown that while microfinance is a business per se,<br />

it is also a powerful development tool. Access to finance, even in the<br />

form of very modest loans, generates huge business productivity gains<br />

and contributes to alleviating poverty in the emerging markets. By<br />

enhancing the living standards of entrepreneurs and their families –<br />

and by empowering women – microfinance provides a significant

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—17<br />

contribution to achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals.<br />

Many investors, especially private investors, who target the microfinance<br />

market, do so with social objectives. While anecdotal evidence<br />

and surveys conducted among the recipients of microloans provide<br />

evidence of the genuine social impact, no universally acceptable<br />

standards exist yet for reporting on the social performance. Initiatives<br />

are targeted in this direction, but more efforts need to be put into<br />

developing and reporting standardized measurements of social impact<br />

at a reasonable cost.<br />

æ<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong> harks back to the Raiffeisen idea<br />

The concept of microfinance is frequently publicized in the media<br />

through accounts of the success story of the Bangladesh-based<br />

Grameen Bank and its more than four million borrowers. Grameen<br />

Bank was founded in 1974 by Prof. Muhammed Yunus for the<br />

express purpose of extending microloans to needy women to<br />

assist them in helping themselves and improving their families’<br />

living conditions. In actuality, though, microfinance is not a novel<br />

invention. It is also no coincidence that the concept proliferated in<br />

western Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. The<br />

Raiffeisen philosophy arose 150 years ago in Germany under difficult<br />

economic circumstances analogous to what one encounters<br />

today in many developing regions. On the cusp of industrialization,<br />

craftsmen and farmers suffered from a scarcity of financial resources<br />

because capital was being drawn to the higher returns promised<br />

by alternative investment opportunities such as railways and<br />

textile factories.<br />

The Raiffeisen model developed by mayor and social reformer<br />

Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen was based on the self-help and solidarity<br />

principle. The farmers and craftsmen of individual villages<br />

banded together into cooperative associations. The members of<br />

each association declared their willingness to pledge their property<br />

as collateral for the cooperative’s liabilities. Since the members<br />

of the cooperative resided in an easily surveyable area, the<br />

character of the borrowers could be taken into account alongside<br />

their material property in the lending decision. The joint liability<br />

enhanced the creditworthiness of the cooperative members and<br />

gave them access to affordable business credit for the purchase<br />

of livestock, fodder, fertilizer and seed, and for their workshops.<br />

They also acquired a safe means of investing their savings. The<br />

Raiffeisen movement spread throughout the German-speaking<br />

world and beyond. The Union of Swiss Raiffeisen Banks was founded<br />

in 1902. In France, the same credit cooperatives go by the name<br />

Crédit Mutuel. And somewhat similar models emerged in other<br />

European nations such as Great Britain in the nineteenth century.<br />

Table 1<br />

Major lending methodologies in microfinance<br />

Source: Zeller, Manfred. Promoting Institutional Innovation in <strong>Microfinance</strong> – Replicating Best Practices is Not Enough.<br />

D+C Development and Cooperation, January 2000; Credit Suisse<br />

Cooperative model Solidarity groups Village banks<br />

Participation p The cooperative members are the owners p Ownership often unclear<br />

p 3 to 10 clients build a group<br />

Structure<br />

p Each cooperative is geographically limited<br />

p Joined support center exists (disbursement<br />

p Regional/central union<br />

of loans, collection of savings, etc.)<br />

Responsibility<br />

p Members vote/elected democratically<br />

p Support center makes decisions<br />

p Financial liability limited to own shares<br />

p Members collectively guarantee loan repayment<br />

p Equity capital build-up by members/the community<br />

p Highly decentralized<br />

p Ideally independent of any upper-level organization<br />

p Committee elected by, and among, members<br />

Profit sharing p Improve balance sheet or payout to members p Improve balance sheet; no distribution p Improve balance sheet or payout to members

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—18<br />

Davos roundtable // Globalization is a powerful process, but it has not yet resolved the<br />

problem of widespread poverty in many parts of the world. Is microfinance a possible,<br />

sustainable solution for the promotion of business initiatives at the bottom of the social<br />

pyramid? Is there an untapped market for the creation of jobs and income?<br />

Ernst A. Brugger / The Substainability Forum Zurich<br />

The following is an edited transcript of the roundtable discussion that took place in Davos, Switzerland on 28 January 2005.<br />

Is access to capital a key<br />

factor for development?<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Globalization is a powerful process, but it still<br />

excludes a majority of the world’s population. Is it correct that out of 6.5<br />

billion people in the world, globalization has not yet reached about four<br />

billion people? Is there a hidden, huge market, neglected by statistics,<br />

business and politics?<br />

Jane Nelson // I think that’s the right picture in terms of up to<br />

4 billion people residing at the bottom of the so-called economic<br />

pyramid. In terms of funds, access to credit and other basic resources,<br />

they need development, not only in economic terms, but also in terms<br />

of basic human development. The potential for micro- and small-scale<br />

businesses is huge. To me, the big challenge is how to deliver products<br />

and financial services to that potential market in an efficient and<br />

equitable way.<br />

Hernando de Soto // We’ve got some detailed figures for some<br />

countries. In Mexico, for example, after working there for about a year<br />

at the request of President Vicente Fox, we’re talking about six million<br />

enterprises that are outside the legal system, most of which are familyowned<br />

microbusinesses. This corresponds to roughly 40–50 million<br />

human beings out of a population of 100 million.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // And what kind of hidden value do they<br />

produce?<br />

Hernando de Soto // These people – i.e., the extralegal sector<br />

– actually own around 11 million plots of land or buildings that cover<br />

a total of about 134 million hectares. Now, we also have additional<br />

statistics that tell us that 49% of the population of Mexico is employed<br />

full-time outside the legal sector. What the extralegal sector has in<br />

assets is the machinery and equipment in the six million enterprises,<br />

the 134 million hectares of land and the buildings valued at about USD<br />

315 billion that are situated on this land. This is equal to seven times<br />

the value of Mexico’s oil reserves. We use this comparison because<br />

we say the greatest resource that a country has is actually its people,<br />

and these USD 315 billion correspond to 31 times the amount of<br />

foreign direct investment that Mexico has received – mainly from the<br />

United States – since the Mexican Revolution. There is a lot of potential<br />

tied up there.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Why does this extensive extralegal market<br />

really exist?<br />

Hernando de Soto // What we do is not only size up what we<br />

call the extralegal sector, but also find out why it’s outside the system.<br />

Basically, it is about bad rules of law. And the next thing that we want<br />

to find out is how to bring the extralegal sector inside. And one >

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—19<br />

Ernst A. Brugger<br />

The Sustainability<br />

Forum Zurich<br />

Roshaneh Zafar<br />

Kashf Foundation<br />

Roshaneh Zafar: A lot of women are actually providing income for their families in the microbusiness sector, but they are not recognized.<br />

There is no training and no support. That’s why we offer access to microcredit.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—20<br />

Walter B. Kielholz<br />

Credit Suisse<br />

Paola Ghillani<br />

previously CEO of<br />

Max Havelaar<br />

Paola Ghillani: We may have scope for cooperation with microfinance institutions to serve our suppliers.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—21<br />

“The most important element that we can<br />

contribute is to put projects out in the marketplace<br />

where people can see that this is a real<br />

investment and that investors have a genuine<br />

interest in microfinance.” // Walter B. Kielholz<br />

of the ways, of course, to bring the extralegal sector inside is for the<br />

government to make a proposal clarifying quite clearly that this sector<br />

has to conform to the rules of law. One of the things you add to the<br />

package is, how does the sector access the sizeable benefits? How<br />

can people operating in the extralegal sector obtain credit? How can<br />

they get electricity? So this is starting to give the informal sector all<br />

the benefits that everyone who lives in the formal sector enjoys.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Let’s take the example of Pakistan. Does<br />

that country also have a huge informal sector?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // Actually, 65% of the country’s current<br />

employment is in the informal sector. I actually don’t like using the<br />

term “informal sector.” I prefer to call it the micro- and small-enterprise<br />

sector, because once you talk about an informal sector, you are basically<br />

saying it’s a tertiary economy, which it isn’t. It’s a primary economy<br />

really; if we are saying “informal sector,” we’re not recognizing the<br />

input – the fact that these businesses provide employment in the<br />

country. If you look at job creation, every year there are 3.1 million<br />

people entering the market in Pakistan looking for jobs. Over 75% of<br />

them find jobs in the micro- and small-enterprise sector. That’s why<br />

it’s a major source of employment for people in the country. My perspective<br />

on this is a woman’s perspective. If you look at the labor force<br />

participation rate in Pakistan, it’s 24% right now – that’s the official<br />

rate. But when we turn to the informal sector, the percentage rate is<br />

up in the high fifties. The reason why I’m providing this backdrop is to<br />

talk about the impact that a microcredit program especially for women<br />

would have. The government does not recognize women as active<br />

economic elements in the country. Why? There are two reasons. One,<br />

because the government does not record these businesses; they’re<br />

really not within the spectrum of taxable income brackets, so they’re not<br />

licensed, they’re not registered, there is no counting, they’re very<br />

informal in the way they do business and they’re really not recognized.<br />

And two, a lot of women are actually providing income for their families<br />

in this sector, but they do not receive support, there is no training, there<br />

is no opportunity and no access to credit. They’re huge numbers. The<br />

overall population of Pakistan is 140 million at present, and if we turn<br />

this around and look at the demand for microfinance in the country,<br />

the estimate is that there are 5.6 million households that require access.<br />

If we look at the market penetration of the largest microfinance providers<br />

in the country, they do not even cover five percent of the market<br />

demand. Which means that 95% of the market is underserved.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Walter Kielholz, when you listen to these<br />

numbers, are they a big surprise to you, or do you think this is a reality<br />

that is well known in the international banking system?<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // Well, the banking industry knows that something<br />

is going on below the top ten percent of the economic pyramid.<br />

The informal sector seems to be so important and has its laws and<br />

rules as to how it works, and it must have a way to allocate resources.<br />

People must be very smart, because otherwise the sector wouldn’t<br />

survive. There is indeed a market in the informal sector – and it<br />

works.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // But it has major constraints; it’s not a value<br />

proposition for the household. I agree it’s a market that functions, but<br />

it’s not an efficient market, and it must become more efficient for the<br />

people. The majority of our clients (we have 70,000 clients now) still<br />

need the moneylenders as much as the popular lottery because my<br />

organization cannot actually offer them full service, including savings<br />

accounts, because it’s not a fully organized bank.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // So the informal market is a huge, but inefficient<br />

market with high transaction costs.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // It’s very heavy on transaction costs.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Hernando, do you agree?<br />

Hernando de Soto // Well, the constraints that you were mentioning<br />

are important. Looking at the United States, we know that<br />

85% of all employment there comes from small enterprises. And most<br />

of these small enterprises in the United States obtain their start-up<br />

capital from mortgages used as collateral. The question is: Can you<br />

mobilize your collateral? So to give you an idea, in the case of Egypt,<br />

if you want to formally open a bakery, it takes about 549 days working<br />

eight hours a day. The result is that you do not have any legal bakeries.<br />

Which means you do not have the documents to identify your assets,<br />

you do not have the documents to identify your collateral, and you do<br />

not have efficient access to credit.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Why does it take so much time to formalize<br />

a bakery?<br />

Hernando de Soto // Because you have to comply with government<br />

rules; you have to report to 33 different government offices.<br />

The average time it takes to formally establish a business in Egypt is<br />

between 300 and 400 days. It’s red tape and it’s also corrupt bureaucracy.<br />

I repeat: To go into the bakinvg business there are 33 government<br />

offices; there are 29 different offices that you have to apply to<br />

if you want to get into real estate. In the case of Mexico, to give you<br />

an idea, forming a limited liability company takes a minimum of 17<br />

months working eight hours a day; and if you want to close a mortgage<br />

it takes 16 months; if you want to open a mortgage it takes about<br />

20 months. >

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—22<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Your life is over by then…<br />

Hernando de Soto // That’s right. So the result is the creation –<br />

and we also don’t like the word “informal” – of the extralegal market.<br />

But anyhow, a big part of the problem is constraints, and they’re<br />

absolutely useless. In other words, it’s simply government disorder.<br />

It’s collateral damage to a great extent – a result of the fact that the<br />

government churns out about 28,000 ordinances a year. That’s about<br />

106 a day, and nobody knows whose hand is in whose pockets and<br />

which law is really effective. Viewed from the perspective of the poor,<br />

which is what we’re trying to do, there is a grass-roots base from<br />

which we can create a constituency for change. It’s no longer an<br />

imported American issue (or neoliberal program), the poor themselves<br />

want to do it. It’s something that stifles the poor, and so you create a<br />

constituency for change that every politician should like. Anyhow, the<br />

idea is that, yes, you’ve got this other system that we were talking<br />

about, you’ve got all these other rules. The problem with these other<br />

rules is that it’s not one system of rules, it’s a thousand systems of rules:<br />

each community has one, you can go three blocks, you can go fifteen<br />

blocks, each community has it’s anarchy. But anarchy is not chaos,<br />

anarchy means a variety of little systems as you had in Switzerland<br />

before Eugen Huber put all these things together.<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // It sounds very familiar; all industrialized<br />

countries were developing nations at some stage and have gone<br />

through this process at some time.<br />

Giles Keating // You’re talking about collateral, but mind that<br />

at times a lot of microfinance is being done on the basis of trust and<br />

a kind of peer pressure.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // That’s a good point. It’s actually the way the<br />

market is created. You have poverty lending programs in Asia that usually<br />

have loan sizes of up to 300 to 500 dollars. Lending in Latin America<br />

goes up to 1,000 or 1,500 dollars. When you’re talking about poverty<br />

lending programs, mostly these are based on credibility. How is credibility<br />

gauged? There are several models that work. There are so-called<br />

solidarity lending programs, where you build groups and these become<br />

the unit of transaction. There are many reasons behind this: one is to<br />

lower the cost of transaction, which means, for example, that we use<br />

25 women as one unit of transaction, which means all their loans are<br />

recorded as one, and that cuts down on supervision and monitoring.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Do you also do individual lending?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // Our organization does solidarity lending and<br />

individual lending. It depends on the loan size: when loan sizes increase<br />

to USD 800, we begin to look at collateral. How do you do collateral<br />

with poor people?<br />

Since there is no efficient market mechanism for collateral, we<br />

take co-guarantors. These are people who actually have income tax<br />

statements or are salaried workers. We use them as proxy collateral.<br />

And the next thing we do is also look at property titles. And as<br />

Hernando pointed out, people didn’t want property rights. When we<br />

told them that we were willing to transfer title to them, that we would<br />

walk them through the process and negotiate a transaction for them,<br />

they were still not interested. They didn’t want to get caught up in the<br />

tax net and didn’t want to be documented. And, of course, there are<br />

good reasons for that, because there is corruption, there is nepotism,<br />

there is collusion, there are other transaction issues, and the poor are<br />

scared. These are crucial problems in my part of the world. Litigation<br />

is very common. It’s a very litigious society, and litigation usually centers<br />

on two things, property or personal feuds, family feuds. Those<br />

are the two reasons. People are very scared of the law.<br />

Hernando de Soto // We must remember, they reject the legal<br />

system, not the property rights, because the system is what takes 17<br />

months to enter, it’s what requires 549 days to register a business.<br />

So, of course they don’t want it. It’s the fact that none of these various<br />

property titles helped you to get into the formal economy to begin with,<br />

so they make no sense. If the title is just for taxing, but titleholders<br />

are not connected to the banks, then why should they want titles.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // And so, in our case, credibility is built over<br />

time. It’s like credit-card operations. As I see it, microfinance is very<br />

similar to a credit card; you have a limit, you repay a loan, your limit<br />

is raised. In some ways we are documenting these people. And<br />

recently in Pakistan we decided to set up a credit bureau for microfinance<br />

institutions. The government is not doing it. So we decided to<br />

engage with the private sector, and we emulated, for example, the<br />

case of the Bolivian market, where a credit bureau does exist. So in<br />

some ways people are documented, but again, it’s not formal.<br />

Hernando de Soto // But it’s a logical first stage. It gradually<br />

evolves to encompass those who are more adventurous, other types<br />

of legislation, and then later you start doing the formal lending. So<br />

there is always this 20- to 30-year period before you actually get to<br />

the formal sector in the developing countries.<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // I wanted to come back to this element of<br />

trust or credibility mentioned before. It is actually nothing other than<br />

the sole criterion for a successful allocation of capital. Why? Otherwise<br />

what are the criteria? There are no files, no numbers, no collateral,<br />

and so on. The only thing is trust. That’s why I think the question in<br />

microfinancing is about the front side and the cost involved.<br />

What’s important is that the individual decision at the front end is<br />

right, because if that decision is wrong, the system is corrupted and<br />

the money flows into the wrong channels.<br />

Hernando de Soto // May I just add something there? One of

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—23<br />

“The existence of the extensive extralegal<br />

market is the result of constraints<br />

because of an improper system. It’s<br />

simply government disorder. It works<br />

against the poor. So you have to create a<br />

constituency for change.” // Hernando de Soto<br />

the ways to look at the issue is that to a great degree it is based on<br />

trust, reflected in the fact that the English word credit comes from the<br />

Latin word “credere,” meaning “I believe in you because you have something<br />

to lose.” We found out that a lot of the poor do have assets, have<br />

something to lose, but it doesn’t mean that they can use them as collateral.<br />

It means that they possess an asset that can be developed, but<br />

until you dismantle all these extralegal, dispersed structures that allow<br />

people to deal with each other at a local level, trust cannot be fostered.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Let’s continue with this important train of<br />

thought. Two questions: First, how do you ensure that you make the<br />

right decisions at the front end? Second, isn’t it the case that poor<br />

people cannot afford not to pay back a loan, because if they don’t repay<br />

they risk falling into this really illegal sector with its very high costs?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // I will answer the first question. If I were a<br />

bank and wanted to lend to the poor, my biggest problem would be<br />

asymmetry of information. How do I know who’s credible and who isn’t?<br />

The way we do it, and it’s something that has been tested, you let the<br />

community decide. It’s a principle of involvement and participation and<br />

the principle of self-selection. If you’re running a solidarity lending<br />

program, what you do is let the group decide who comes into the<br />

group. Then you have a second way to verify. We use what engineers<br />

call a triangle of information: you collect the same data from three<br />

different points. I think any researcher would do that too. So you first<br />

let the community decide, then you go to their houses and you see<br />

that they are genuinely credible and actually live there, and the third<br />

person you go to is someone from the community who is not linked to<br />

them. Usually you would go and check that information with the local<br />

grocery store. Because that’s where they have lines of credit. And<br />

you know instantly who’s been paying their credit and who hasn’t.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // So it’s like social engineering…<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // Absolutely. We are basing our entire credit<br />

decision on the person’s reputation. We’re not basing it on the business<br />

proposition.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // And the result?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // In our case, and in most microfinance<br />

instances, if it’s done right, the recovery rate is above 99%. So obviously<br />

we are doing something right with the principle of self-selection.<br />

That’s if you’re talking about credibility or solidarity in generating social<br />

capital; you can’t do it without ownership. Now, coming back to the<br />

issue of costs. You know the transaction cost or the cost of delivery<br />

becomes very important, and that’s a big challenge. If you look at the<br />

alternatives on the market, there is another option: it’s the moneylender.<br />

We’ve done a lot of research to discover what moneylenders<br />

do right. They’re the tougher ones. They provide the client immediate<br />

access. The moment you need money, they will put it in your hands.<br />

But they are charging something like 200% or 360% interest per year<br />

on their loans. It is completely outrageous.<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // The important part is the decision-making,<br />

and that’s why it has to be done properly. The moneylender is actually<br />

spending a lot of money trying to recollect the loan, by all kinds<br />

of means.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // That’s right. But if you compare their pricing<br />

with our service charge or interest rate of 20%, the household finds<br />

this to be very economical. At the same time, we have to charge that<br />

rate because it costs us on average 15%. For every dollar that we lend<br />

in the market, it costs us 15 cents to recover the money. So it’s a very<br />

labor-intensive, cost-intensive service because it’s small tickets and<br />

high volume. And because you are offering service delivery; you are<br />

going to the client.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // So it’s about efficiency and professionalism in<br />

microcredit. We have about 5,000 microfinance institutions in the market,<br />

and I would place only about 10% of those in the top tier of professionally<br />

managed financial institutions, which probably serve around 50<br />

million people. The rest are largely working in a development-aid mode,<br />

subsidized by aid money. Jane, would you agree with these estimates?<br />

Jane Nelson // That’s roughly correct. My sense is that there are<br />

obstacles to overcome in learning the best practices of the more commercially<br />

oriented and sophisticated microfinance institutions. I think<br />

part of the reason probably is that there have been more aid-driven<br />

initiatives and fewer major commercial banks coming through.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Can you imagine, Walter Kielholz, that this<br />

could become a mainstream banking business?<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // Maybe one day, but it will take a very long<br />

time. I think there was a monetization in society in the nineteenth<br />

century which took place because there was a rural exchange community<br />

here in Switzerland. It took a very long time. It’s principally not<br />

a funding problem, but rather a question of how to bring it to the<br />

forefront. It reminds me really of the Raiffeisen movement.<br />

However, the increasing demand for financial services in developing<br />

countries will further advance this development. That’s also the<br />

reason we have joined with other financial institutions to provide a<br />

platform for microfinance investments for our clients. Of course, this<br />

is only a small step, but it shows that there are possibilities to act as<br />

a financial intermediary and to contribute to bridge the gap between<br />

the financial markets and developing countries. >

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—24<br />

Jane Nelson<br />

Harvard University<br />

Hernando de Soto<br />

Instituto Libertad y<br />

Democracia<br />

Giles Keating<br />

Credit Suisse<br />

Giles Keating: We should bring microfinance into the mainstream, to have it as something that is regarded as natural and into which<br />

investors want to put their money.

GLOBAL INVESTOR FOCUS<br />

<strong>Microfinance</strong>—25<br />

“Around four billion people live at the<br />

bottom of the economic pyramid.<br />

So, the potential for micro- and smallscale<br />

businesses is huge.” // Jane Nelson<br />

Giles Keating // As a bank, we would like to take some of the<br />

existing microfinance portfolios and securitize them and then market<br />

the securitization. We want private clients to assume the risk, and we<br />

think they will be happy to do that, particularly in view of the high<br />

quality of the portfolio. I spoke to a couple of clients in Asia a couple<br />

of weeks ago, and the people there said there is immense interest<br />

among our big private clients who’ve contributed charitably to the<br />

tsunami relief, and now they’re interested in helping in the medium<br />

term. One of the ways that they’re interested is that microfinance<br />

can help.<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // That’s indeed an interesting role for us,<br />

because it’s commercial and not pure charity.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // It can be a commercial value. The return on<br />

assets alone, right now, is 10%. The good organizations are financially<br />

viable. They would be able to pay out a return to investors. Interestingly,<br />

there are only two microfinance securitization vehicles in the world,<br />

the one by ICICI Bank in India and the other by BlueOrchard together<br />

with OPIC. So there are only two in existence so far, which is surprising.<br />

But I know why. Because the banks don’t trust us. It took us ages;<br />

it took us ten years as an NGO to get a loan from a local bank. If we<br />

talk about credibility, it’s not just the credibility of the poor, it’s also<br />

the credibility of the NGOs and microfinance institutions.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Is it because of a lack of professionalism<br />

on the part of microfinance institutions?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // We are a high-volume, small-ticket business.<br />

Professionalism is crucial. How will we use technology to cut<br />

down costs, how do we make it more efficient? It has happened in<br />

Latin America with ATMs, for example. If you look at Bolivia, Indian<br />

women in the remotest village have an ATM machine and fingerprint<br />

technology to get credit. It can be done.<br />

Giles Keating // How about equity capital. What’s the vision<br />

here?<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // If you’re first an NGO, it’s donated equity.<br />

When you transform into a commercial enterprise, you license yourself<br />

into a bank, which we are hoping to do in the near future. So that is when<br />

you need equity investors who are like-minded. Because once you’re<br />

licensed, your transaction costs will change, the returns will change, the<br />

whole business will change, and the market will change. So you need<br />

the initial capital and you need people who invest in microfinance.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Jane, how do you see the role of big banks<br />

in the market?<br />

Jane Nelson // Take the perspective of Credit Suisse or any bank<br />

that wants to get into this. It seems to me that there are four ways in<br />

which you can become engaged: through commercial products and<br />

services, through portfolio securitization or equity capital or whatever,<br />

and through philanthropic venture capital projects. And then, fourthly,<br />

through activities to influence the policy dialogue for better framework<br />

conditions.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // Paola, you are a commercial buyer. Max<br />

Havelaar is one of the leading commercial agents for socially and<br />

ecologically responsible products in Switzerland, and you are the CEO<br />

and have brought the company up to an impressive level that was<br />

unimaginable some years ago. How do you treat your suppliers, the<br />

small agribusinesses? Do you extend them credit?<br />

Paola Ghillani // No, I’m not a specialist in microcredit. We do<br />

fair trade labeling, and our mission and task is to open the market to<br />

disadvantaged producers and workers from developing countries<br />

under fair trade conditions. And we control and certify the products<br />

they sell to importers and retailers in our country.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // And no links to microfinance institutions?<br />

Paola Ghillani // No, not yet. But our discussion shows that we<br />

may have scope for cooperation with microfinance institutions interested<br />

in serving our suppliers. I would be interested in exploring this<br />

idea and in experimenting with some concrete projects.<br />

Ernst A. Brugger // That leads directly to my last question to everybody<br />

in the round: What would you say is the most important priority<br />

for developing this microfinance market? One priority or one wish.<br />

Roshaneh Zafar // Scale. Scale up, we have to do that.<br />

Paola Ghillani // I think it’s about systemization and efficiency<br />

in the evaluation process.<br />

Jane Nelson // Scaling up the existing microfinance institutions<br />

and creating many more.<br />

Walter B. Kielholz // I think the most important thing that we<br />