Scythian Culture - Preservation of The Frozen Tombs of The Altai Mountains (UNESCO)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CHAPTER I • SCYTHIANS IN THE EURASIAN STEPPE AND THE PLACE OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS IN IT<br />

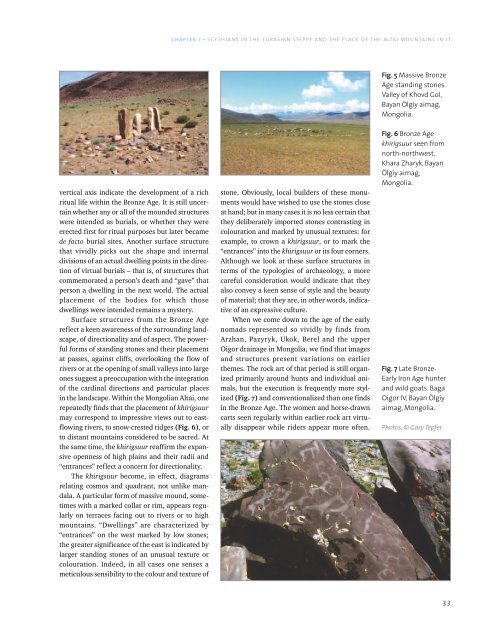

Fig. 5 Massive Bronze<br />

Age standing stones.<br />

Valley <strong>of</strong> Khovd Gol,<br />

Bayan Ölgiy aimag,<br />

Mongolia.<br />

vertical axis indicate the development <strong>of</strong> a rich<br />

ritual life within the Bronze Age. It is still uncertain<br />

whether any or all <strong>of</strong> the mounded structures<br />

were intended as burials, or whether they were<br />

erected first for ritual purposes but later became<br />

de facto burial sites. Another surface structure<br />

that vividly picks out the shape and internal<br />

divisions <strong>of</strong> an actual dwelling points in the direction<br />

<strong>of</strong> virtual burials – that is, <strong>of</strong> structures that<br />

commemorated a person’s death and “gave” that<br />

person a dwelling in the next world. <strong>The</strong> actual<br />

placement <strong>of</strong> the bodies for which those<br />

dwellings were intended remains a mystery.<br />

Surface structures from the Bronze Age<br />

reflect a keen awareness <strong>of</strong> the surrounding landscape,<br />

<strong>of</strong> directionality and <strong>of</strong> aspect. <strong>The</strong> powerful<br />

forms <strong>of</strong> standing stones and their placement<br />

at passes, against cliffs, overlooking the flow <strong>of</strong><br />

rivers or at the opening <strong>of</strong> small valleys into large<br />

ones suggest a preoccupation with the integration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the cardinal directions and particular places<br />

in the landscape. Within the Mongolian <strong>Altai</strong>, one<br />

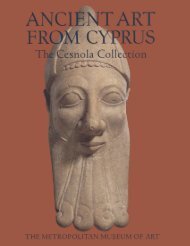

repeatedly finds that the placement <strong>of</strong> khirigsuur<br />

may correspond to impressive views out to eastflowing<br />

rivers, to snow-crested ridges (Fig. 6), or<br />

to distant mountains considered to be sacred. At<br />

the same time, the khirigsuur reaffirm the expansive<br />

openness <strong>of</strong> high plains and their radii and<br />

“entrances” reflect a concern for directionality.<br />

<strong>The</strong> khirigsuur become, in effect, diagrams<br />

relating cosmos and quadrant, not unlike mandala.<br />

A particular form <strong>of</strong> massive mound, sometimes<br />

with a marked collar or rim, appears regularly<br />

on terraces facing out to rivers or to high<br />

mountains. “Dwellings” are characterized by<br />

“entrances” on the west marked by low stones;<br />

the greater significance <strong>of</strong> the east is indicated by<br />

larger standing stones <strong>of</strong> an unusual texture or<br />

colouration. Indeed, in all cases one senses a<br />

meticulous sensibility to the colour and texture <strong>of</strong><br />

stone. Obviously, local builders <strong>of</strong> these monuments<br />

would have wished to use the stones close<br />

at hand; but in many cases it is no less certain that<br />

they deliberately imported stones contrasting in<br />

colouration and marked by unusual textures: for<br />

example, to crown a khirigsuur, or to mark the<br />

“entrances” into the khirigsuur or its four corners.<br />

Although we look at these surface structures in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> the typologies <strong>of</strong> archaeology, a more<br />

careful consideration would indicate that they<br />

also convey a keen sense <strong>of</strong> style and the beauty<br />

<strong>of</strong> material; that they are, in other words, indicative<br />

<strong>of</strong> an expressive culture.<br />

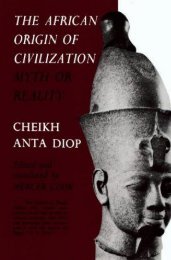

When we come down to the age <strong>of</strong> the early<br />

nomads represented so vividly by finds from<br />

Arzhan, Pazyryk, Ukok, Berel and the upper<br />

Oigor drainage in Mongolia, we find that images<br />

and structures present variations on earlier<br />

themes. <strong>The</strong> rock art <strong>of</strong> that period is still organized<br />

primarily around hunts and individual animals,<br />

but the execution is frequently more stylized<br />

(Fig. 7) and conventionalized than one finds<br />

in the Bronze Age. <strong>The</strong> women and horse-drawn<br />

carts seen regularly within earlier rock art virtually<br />

disappear while riders appear more <strong>of</strong>ten.<br />

Fig. 6 Bronze Age<br />

khirigsuur seen from<br />

north-northwest.<br />

Khara Zharyk, Bayan<br />

Ölgiy aimag,<br />

Mongolia.<br />

Fig. 7 Late Bronze-<br />

Early Iron Age hunter<br />

and wild goats. Baga<br />

Oigor IV, Bayan Ölgiy<br />

aimag, Mongolia.<br />

Photos: © Gary Tepfer.<br />

33