Scythian Culture - Preservation of The Frozen Tombs of The Altai Mountains (UNESCO)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CHAPTER I • SCYTHIANS IN THE EURASIAN STEPPE AND THE PLACE OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS IN IT<br />

the latter feature ultimately originates in<br />

Achaemenid art. Other, more specific motifs<br />

include the one termed the “cloud” in China,<br />

which has been found at Jiaohe and Goubei in<br />

Xinjiang, along with the motif <strong>of</strong> a bird’s scaly<br />

feathers. Both motifs first appeared at Tuekta-1<br />

(400-440 bce) in the <strong>Altai</strong> during an early phase<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Pazyryk <strong>Culture</strong>.<br />

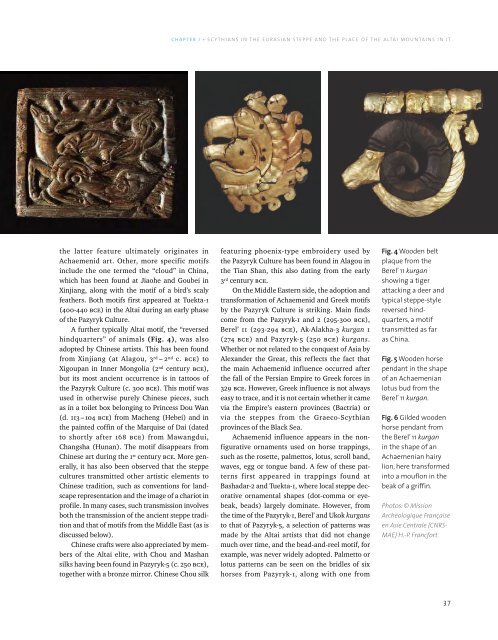

A further typically <strong>Altai</strong> motif, the “reversed<br />

hindquarters” <strong>of</strong> animals (Fig. 4), was also<br />

adopted by Chinese artists. This has been found<br />

from Xinjiang (at Alagou, 3 rd –2 nd c. bce) to<br />

Xigoupan in Inner Mongolia (2 nd century bce),<br />

but its most ancient occurrence is in tattoos <strong>of</strong><br />

the Pazyryk <strong>Culture</strong> (c. 300 bce). This motif was<br />

used in otherwise purely Chinese pieces, such<br />

as in a toilet box belonging to Princess Dou Wan<br />

(d. 113 – 104 bce) from Macheng (Hebei) and in<br />

the painted c<strong>of</strong>fin <strong>of</strong> the Marquise <strong>of</strong> Dai (dated<br />

to shortly after 168 bce) from Mawangdui,<br />

Changsha (Hunan). <strong>The</strong> motif disappears from<br />

Chinese art during the 1 st century bce. More generally,<br />

it has also been observed that the steppe<br />

cultures transmitted other artistic elements to<br />

Chinese tradition, such as conventions for landscape<br />

representation and the image <strong>of</strong> a chariot in<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile. In many cases, such transmission involves<br />

both the transmission <strong>of</strong> the ancient steppe tradition<br />

and that <strong>of</strong> motifs from the Middle East (as is<br />

discussed below).<br />

Chinese crafts were also appreciated by members<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Altai</strong> elite, with Chou and Mashan<br />

silks having been found in Pazyryk-5 (c. 250 bce),<br />

together with a bronze mirror. Chinese Chou silk<br />

featuring phoenix-type embroidery used by<br />

the Pazyryk <strong>Culture</strong> has been found in Alagou in<br />

the Tian Shan, this also dating from the early<br />

3 rd century bce.<br />

On the Middle Eastern side, the adoption and<br />

transformation <strong>of</strong> Achaemenid and Greek motifs<br />

by the Pazyryk <strong>Culture</strong> is striking. Main finds<br />

come from the Pazyryk-1 and 2 (295-300 bce),<br />

Berel’ 11 (293-294 bce), Ak-Alakha-3 kurgan 1<br />

(274 bce) and Pazyryk-5 (250 bce) kurgans.<br />

Whether or not related to the conquest <strong>of</strong> Asia by<br />

Alexander the Great, this reflects the fact that<br />

the main Achaemenid influence occurred after<br />

the fall <strong>of</strong> the Persian Empire to Greek forces in<br />

329 bce. However, Greek influence is not always<br />

easy to trace, and it is not certain whether it came<br />

via the Empire’s eastern provinces (Bactria) or<br />

via the steppes from the Graeco-<strong>Scythian</strong><br />

provinces <strong>of</strong> the Black Sea.<br />

Achaemenid influence appears in the nonfigurative<br />

ornaments used on horse trappings,<br />

such as the rosette, palmettos, lotus, scroll band,<br />

waves, egg or tongue band. A few <strong>of</strong> these patterns<br />

first appeared in trappings found at<br />

Bashadar-2 and Tuekta-1, where local steppe decorative<br />

ornamental shapes (dot-comma or eyebeak,<br />

beads) largely dominate. However, from<br />

the time <strong>of</strong> the Pazyryk-1, Berel’ and Ukok kurgans<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> Pazyryk-5, a selection <strong>of</strong> patterns was<br />

made by the <strong>Altai</strong> artists that did not change<br />

much over time, and the bead-and-reel motif, for<br />

example, was never widely adopted. Palmetto or<br />

lotus patterns can be seen on the bridles <strong>of</strong> six<br />

horses from Pazyryk-1, along with one from<br />

Fig. 4 Wooden belt<br />

plaque from the<br />

Berel’ 11 kurgan<br />

showing a tiger<br />

attacking a deer and<br />

typical steppe-style<br />

reversed hindquarters,<br />

a motif<br />

transmitted as far<br />

as China.<br />

Fig. 5 Wooden horse<br />

pendant in the shape<br />

<strong>of</strong> an Achaemenian<br />

lotus bud from the<br />

Berel’ 11 kurgan.<br />

Fig. 6 Gilded wooden<br />

horse pendant from<br />

the Berel’ 11 kurgan<br />

in the shape <strong>of</strong> an<br />

Achaemenian hairy<br />

lion, here transformed<br />

into a mouflon in the<br />

beak <strong>of</strong> a griffin.<br />

Photos: © Mission<br />

Archéologique Française<br />

en Asie Centrale (CNRS-<br />

MAE) H.-P. Francfort.<br />

37