Scythian Culture - Preservation of The Frozen Tombs of The Altai Mountains (UNESCO)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CHAPTER I • SCYTHIANS IN THE EURASIAN STEPPE AND THE PLACE OF THE ALTAI MOUNTAINS IN IT<br />

<strong>The</strong> Silk Roads and the Road <strong>of</strong> the Steppes:<br />

Eurasia and the <strong>Scythian</strong> World<br />

Pierre Cambon<br />

Conservateur en chef<br />

Musée Guimet, France<br />

Following the major foreign archaeological<br />

expeditions – Russian, British, German,<br />

French and Japanese – that took place in Chinese<br />

Tukestan (today’s Xinjiang) between 1900 and<br />

1914 against a background <strong>of</strong> imperial rivalries,<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> the Silk Roads as one <strong>of</strong> the major<br />

routes <strong>of</strong> exchange between the western world,<br />

whether Indian or Iranian, Roman or Mediterranean,<br />

and the Far East or North East Asia, to<br />

which China appeared to be the gateway,<br />

appeared. This idea culminated in the Silk Roads<br />

programme launched by <strong>UNESCO</strong> in the 1990s<br />

and in the “Sérinde” exhibition held at the Grand<br />

Palais in Paris in 1995.<br />

Avoiding the Taklamakan depression, two<br />

main routes joined Kashgar in the West with<br />

Dunhuang in the borderlands <strong>of</strong> China in the<br />

East. <strong>The</strong> older <strong>of</strong> these routes and the furthest<br />

south passed through Khotan and ran south<br />

through the foothills <strong>of</strong> the Himalayas, while the<br />

younger went through Aksou, the Quca oasis and<br />

the Turfan oasis before reaching China. This was<br />

above all a caravan route <strong>of</strong> the type evoked by<br />

Ibn Battuta in his travels, and is was also the<br />

route followed by Chinese pilgrims traveling to<br />

India in search <strong>of</strong> religious texts. It was this latter<br />

route that led to the expansion <strong>of</strong> Buddhism,<br />

which spread alongside the merchants and the<br />

first translators coming from Central Asia, Swat,<br />

or Afghanistan and that pivotal region that Aurel<br />

Stein called “Serindia” to produce a unique<br />

Buddhist form <strong>of</strong> art in the oases, whose style,<br />

codes and iconography influenced traditional<br />

Chinese Asia.<br />

This region was conquered during the Han<br />

period by Chinese armies, lost during the period<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Six Dynasties and re-conquered under the<br />

Tang. It gave rise in the years that followed to the<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> ephemeral empires such as that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Western Turks before the period <strong>of</strong> the Mongol<br />

invasions that overwhelmed China and the<br />

Iranian world during the 12 th century ce under<br />

Genghis Khan and his successors, which realized<br />

beyond his wildest dreams Alexander the Great’s<br />

ambition <strong>of</strong> uniting East and West within a single<br />

empire.<br />

Yet, if the “Silk Roads” in the sense in which<br />

this term is <strong>of</strong>ten understood today means<br />

Chinese Tukestan or contemporary Xinjiang, in<br />

other words, a frontier zone on the edge <strong>of</strong><br />

empires, it nevertheless also denotes a sedentary<br />

world that has its own history. <strong>The</strong> world <strong>of</strong> the<br />

oases and the caravans is not that <strong>of</strong> the steppes<br />

and the nomads, the latter being left out <strong>of</strong> written<br />

history. For many centuries, only indirect echoes<br />

<strong>of</strong> this latter world reached us in the accounts left<br />

by ancient Greek authors or in Chinese annals, as<br />

well as in the later works <strong>of</strong> Arab travelers.<br />

This world <strong>of</strong> movement recedes before us<br />

and is <strong>of</strong>ten compared to the sea or to an ocean<br />

whose boundaries are fluid and changing.<br />

Alexander the Great stopped at the boundaries <strong>of</strong><br />

the sedentary world in Afghanistan and did not<br />

seek to push beyond the Oxus, following the<br />

Achaemenid example in this respect. However,<br />

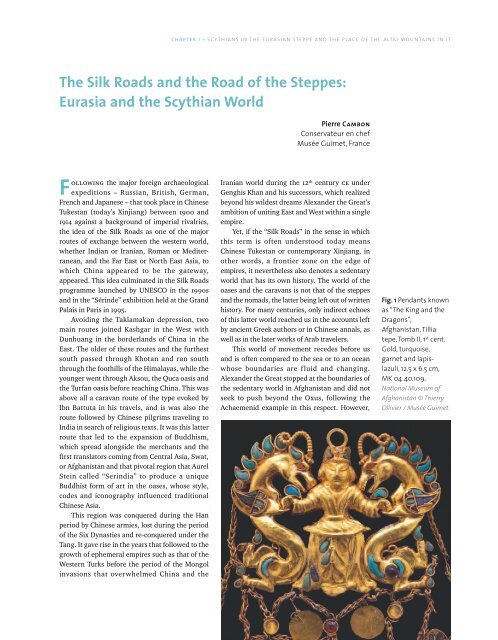

Fig. 1 Pendants known<br />

as “<strong>The</strong> King and the<br />

Dragons”,<br />

Afghanistan, Tillia<br />

tepe, Tomb II, 1 st cent.<br />

Gold, turquoise,<br />

garnet and lapislazuli,<br />

12.5 x 6.5 cm,<br />

MK 04.40.109.<br />

National Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Afghanistan © Thierry<br />

Ollivier / Musée Guimet.