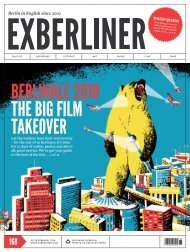

Exberliner Issue 167, January 2018

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

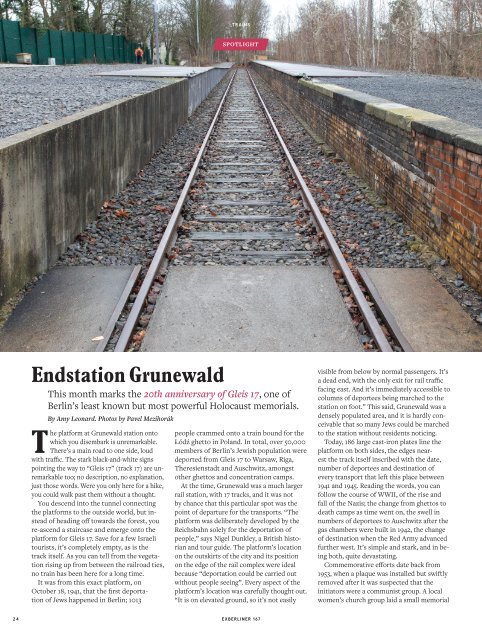

TRAINS<br />

SPOTLIGHT<br />

Endstation Grunewald<br />

This month marks the 20th anniversary of Gleis 17, one of<br />

Berlin’s least known but most powerful Holocaust memorials.<br />

By Amy Leonard. Photos by Pavel Mezihorák<br />

The platform at Grunewald station onto<br />

which you disembark is unremarkable.<br />

There’s a main road to one side, loud<br />

with traffic. The stark black-and-white signs<br />

pointing the way to “Gleis 17” (track 17) are unremarkable<br />

too; no description, no explanation,<br />

just those words. Were you only here for a hike,<br />

you could walk past them without a thought.<br />

You descend into the tunnel connecting<br />

the platforms to the outside world, but instead<br />

of heading off towards the forest, you<br />

re-ascend a staircase and emerge onto the<br />

platform for Gleis 17. Save for a few Israeli<br />

tourists, it’s completely empty, as is the<br />

track itself. As you can tell from the vegetation<br />

rising up from between the railroad ties,<br />

no train has been here for a long time.<br />

It was from this exact platform, on<br />

October 18, 1941, that the first deportation<br />

of Jews happened in Berlin; 1013<br />

people crammed onto a train bound for the<br />

Łódź ghetto in Poland. In total, over 50,000<br />

members of Berlin’s Jewish population were<br />

deported from Gleis 17 to Warsaw, Riga,<br />

Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, amongst<br />

other ghettos and concentration camps.<br />

At the time, Grunewald was a much larger<br />

rail station, with 17 tracks, and it was not<br />

by chance that this particular spot was the<br />

point of departure for the transports. “The<br />

platform was deliberately developed by the<br />

Reichsbahn solely for the deportation of<br />

people,” says Nigel Dunkley, a British historian<br />

and tour guide. The platform’s location<br />

on the outskirts of the city and its position<br />

on the edge of the rail complex were ideal<br />

because “deportation could be carried out<br />

without people seeing”. Every aspect of the<br />

platform’s location was carefully thought out.<br />

“It is on elevated ground, so it’s not easily<br />

visible from below by normal passengers. It’s<br />

a dead end, with the only exit for rail traffic<br />

facing east. And it’s immediately accessible to<br />

columns of deportees being marched to the<br />

station on foot.” This said, Grunewald was a<br />

densely populated area, and it is hardly conceivable<br />

that so many Jews could be marched<br />

to the station without residents noticing.<br />

Today, 186 large cast-iron plates line the<br />

platform on both sides, the edges nearest<br />

the track itself inscribed with the date,<br />

number of deportees and destination of<br />

every transport that left this place between<br />

1941 and 1945. Reading the words, you can<br />

follow the course of WWII, of the rise and<br />

fall of the Nazis; the change from ghettos to<br />

death camps as time went on, the swell in<br />

numbers of deportees to Auschwitz after the<br />

gas chambers were built in 1942, the change<br />

of destination when the Red Army advanced<br />

further west. It’s simple and stark, and in being<br />

both, quite devastating.<br />

Commemorative efforts date back from<br />

1953, when a plaque was installed but swiftly<br />

removed after it was suspected that the<br />

initiators were a communist group. A local<br />

women’s church group laid a small memorial<br />

24<br />

EXBERLINER <strong>167</strong>