Exberliner Issue 167, January 2018

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

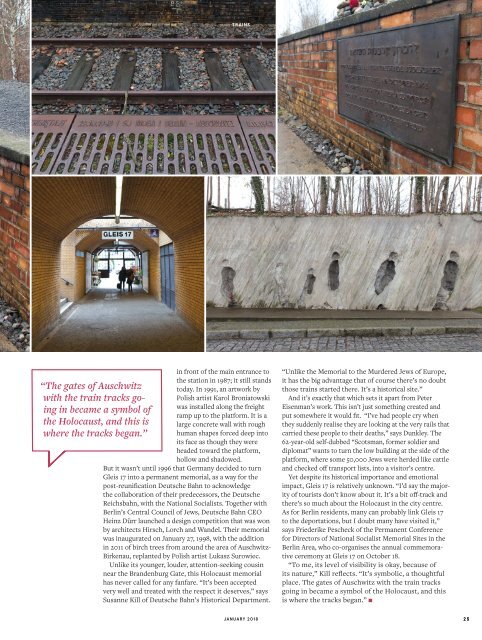

TRAINS<br />

“The gates of Auschwitz<br />

with the train tracks going<br />

in became a symbol of<br />

the Holocaust, and this is<br />

where the tracks began.”<br />

in front of the main entrance to<br />

the station in 1987; it still stands<br />

today. In 1991, an artwork by<br />

Polish artist Karol Broniatowski<br />

was installed along the freight<br />

ramp up to the platform. It is a<br />

large concrete wall with rough<br />

human shapes forced deep into<br />

its face as though they were<br />

headed toward the platform,<br />

hollow and shadowed.<br />

But it wasn’t until 1996 that Germany decided to turn<br />

Gleis 17 into a permanent memorial, as a way for the<br />

post-reunification Deutsche Bahn to acknowledge<br />

the collaboration of their predecessors, the Deutsche<br />

Reichsbahn, with the National Socialists. Together with<br />

Berlin’s Central Council of Jews, Deutsche Bahn CEO<br />

Heinz Dürr launched a design competition that was won<br />

by architects Hirsch, Lorch and Wandel. Their memorial<br />

was inaugurated on <strong>January</strong> 27, 1998, with the addition<br />

in 2011 of birch trees from around the area of Auschwitz-<br />

Birkenau, replanted by Polish artist Lukasz Surowiec.<br />

Unlike its younger, louder, attention-seeking cousin<br />

near the Brandenburg Gate, this Holocaust memorial<br />

has never called for any fanfare. “It’s been accepted<br />

very well and treated with the respect it deserves,” says<br />

Susanne Kill of Deutsche Bahn’s Historical Department.<br />

“Unlike the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,<br />

it has the big advantage that of course there’s no doubt<br />

those trains started there. It’s a historical site.”<br />

And it’s exactly that which sets it apart from Peter<br />

Eisenman’s work. This isn’t just something created and<br />

put somewhere it would fit. “I’ve had people cry when<br />

they suddenly realise they are looking at the very rails that<br />

carried these people to their deaths,” says Dunkley. The<br />

62-year-old self-dubbed “Scotsman, former soldier and<br />

diplomat” wants to turn the low building at the side of the<br />

platform, where some 50,000 Jews were herded like cattle<br />

and checked off transport lists, into a visitor’s centre.<br />

Yet despite its historical importance and emotional<br />

impact, Gleis 17 is relatively unknown. “I’d say the majority<br />

of tourists don’t know about it. It’s a bit off-track and<br />

there’s so much about the Holocaust in the city centre.<br />

As for Berlin residents, many can probably link Gleis 17<br />

to the deportations, but I doubt many have visited it,”<br />

says Friederike Pescheck of the Permanent Conference<br />

for Directors of National Socialist Memorial Sites in the<br />

Berlin Area, who co-organises the annual commemorative<br />

ceremony at Gleis 17 on October 18.<br />

“To me, its level of visibility is okay, because of<br />

its nature,” Kill reflects. “It’s symbolic, a thoughtful<br />

place. The gates of Auschwitz with the train tracks<br />

going in became a symbol of the Holocaust, and this<br />

is where the tracks began.” n<br />

JANUARY <strong>2018</strong><br />

25