ENERGY Caribbean Yearbook (2013-14)

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The annual review of the <strong>Caribbean</strong> energy industry<br />

YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong>

YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

Contents<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> energy map 2-3<br />

Section 1: the big issues<br />

World energy outlook 4<br />

Caricom energy policy 1 6<br />

Caricom energy policy 2 7<br />

Energy security 8<br />

The future of gas 9<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> gas market 10<br />

The green agenda 11<br />

Going international 12<br />

Alternative fuels 13<br />

Trinidad & Tobago’s oil revival 1 <strong>14</strong><br />

Trinidad & Tobago’s oil revival 2 15<br />

Cross-border gas 16<br />

Deep water exploration 17<br />

Independents 18<br />

Climate change 19<br />

Local content 20<br />

Gas-based development 21<br />

Section 2: the energy producers<br />

Trinidad and Tobago 22<br />

Suriname 28<br />

Barbados 30<br />

Belize 32<br />

Jamaica 33<br />

Guyana 34<br />

Cuba 35<br />

Section 3: company profiles<br />

Atlantic 36<br />

CIBC First<strong>Caribbean</strong> International Bank 38<br />

Gasfin Development SA 40<br />

Methanex Trinidad 42<br />

The National Gas Company 44<br />

Repsol Trinidad & Tobago 46<br />

Solaris Energy 48<br />

Written by<br />

David Renwick<br />

Editor<br />

Jeremy Taylor<br />

Sales<br />

Denise Chin<br />

Design<br />

Bridget van Dongen<br />

Administration<br />

Joanne Mendes, Jacqueline Smith<br />

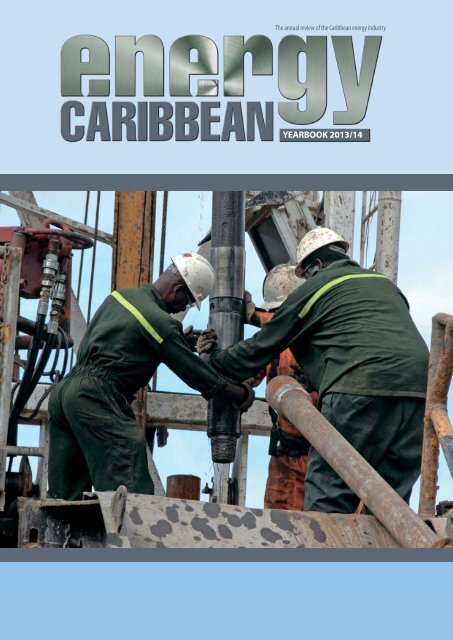

Cover photo<br />

Drilling (courtesy Petrotrin)<br />

The <strong>ENERGY</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> <strong>Yearbook</strong> is<br />

published annually<br />

by Media & Editorial Projects Ltd.,<br />

6 Prospect Avenue, Maraval,<br />

Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago<br />

Tel: (868) 622-3821<br />

Fax: (868) 628-0639<br />

energy@meppublishers.com<br />

Sales: dchin@meppublishers.com<br />

Distributed free to subscribers of the bimonthly<br />

<strong>ENERGY</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> newsletter<br />

Retail price US$25 + p/p<br />

For subscription and retail information<br />

please visit<br />

www.meppublishers.com<br />

or call<br />

(868) 622-3821<br />

© Media & Editorial Projects Ltd. <strong>2013</strong><br />

All rights strictly reserved.<br />

ISSN 1811-1726<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

1

Mississippi R.<br />

Houma<br />

New Orleans<br />

Tallahassee<br />

Orlando<br />

Daytona Beach<br />

USA<br />

Gulf<br />

Miami<br />

of<br />

Nassau<br />

Mexico<br />

Havana<br />

Bahamas<br />

Cuba<br />

Villahermosa<br />

Cayman Islands<br />

Jamaica<br />

Kingston<br />

Ha<br />

Port-au-Prin<br />

Flores<br />

Belize<br />

Tuxtla Gutierrez<br />

C a r i b<br />

Honduras<br />

b e a n<br />

S<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong><br />

energy map<br />

Nicaragua<br />

San José<br />

Maraca<br />

Oil or gas field<br />

Costa Rica<br />

Panama<br />

Panama<br />

Refinery<br />

LNG train<br />

Eastern <strong>Caribbean</strong> gas pipeline<br />

English-speaking territory<br />

French-speaking territory<br />

Dutch-speaking territory<br />

Spanish-speaking territory<br />

P a c i f i c<br />

O c e a n<br />

C<br />

2

A t l a n t i c<br />

O c e a n<br />

Haiti<br />

ort-au-Prince<br />

Maracaibo<br />

Dominican<br />

Republic<br />

S e a<br />

Santo Domingo<br />

Aruba<br />

Oranjestad Curaçao<br />

Bonaire<br />

Willemstad<br />

Valencia<br />

San Juan<br />

Puerto Rico<br />

Caracas<br />

Virgin Islands<br />

Philipsburg St Maarten<br />

St Kitts & Nevis Antigua<br />

Basseterre St John<br />

Montserrat<br />

Pointe-á-Pitre<br />

Guadeloupe<br />

Roseau Dominica<br />

Fort-de-France Martinique<br />

Castries<br />

St Lucia<br />

St Vincent &<br />

the Grenadines<br />

Barbados<br />

Kingstown Bridgetown<br />

St George’s<br />

Grenada<br />

Scarborough Tobago<br />

Port of Spain<br />

Trinidad<br />

N<br />

Venezuela<br />

Georgetown<br />

Colombia<br />

Guyana<br />

Paramaribo<br />

Cayenne<br />

Suriname<br />

French<br />

Guiana<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong> 3

Energy<br />

issues<br />

world energy outlook<br />

Oil price will stay high<br />

Companie<br />

In the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, the international energy outlook is a good deal brighter for<br />

Countries<br />

supply challenge. LNG projects these days are notoriously difficult to deliver.” With<br />

4<br />

oil and gas producers than for consumers.<br />

With reviving economic growth in North America and continued economic<br />

expansion in the Far East, the price of oil is likely to stay within the $95-100<br />

range, well above the cost of production of any reasonably efficient company.<br />

The gas price will probably remain lower in the United States than has been the<br />

case until recently, moving between $4 and $4.50 per mmbtu. But it will continue<br />

strong in major Eastern markets such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and even<br />

in the European Union, where demand for LNG is rising.<br />

Until the US starts to export LNG late in the current decade, pressures on pricing<br />

will intensify. Several LNG projects in other countries are having difficulty getting<br />

off the ground, because of spiralling costs for LNG construction, most notably in<br />

Australia, Canada and Qatar, and because of infrastructural deficiencies in areas<br />

like East Africa, the new hotspot for LNG development.<br />

Spokesmen for the BG Group in the UK, a major LNG trader which operates in<br />

Trinidad and Tobago, insist that “it is not going to be easy to meet an enormous<br />

LNG expected to comprise <strong>14</strong>% of all globally traded gas by 2025, there is clearly<br />

a challenge in bringing enough supply projects on stream to be able to meet this<br />

demand.<br />

The price of oil is likely to stay within the $95-100<br />

range, well above the cost of production of any<br />

reasonably efficient company<br />

Another piece of bad news is that coal could be making a comeback, thanks<br />

to the high cost of oil. The Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA)<br />

suggests, startlingly, that “demand for coal could catch up with oil by 2022.” As<br />

early as 2017, global coal consumption could stand at 4.32 billion tonnes of oil<br />

equivalent, compared with 4.4 billion tonnes for oil itself, the IEA predicts.<br />

This, of course, will be terribly unhealthy for the environment, since coal is<br />

the most polluting fossil fuel, and already over 66% of climate change-causing<br />

emissions emanate from the energy sector.<br />

The expectation was, of course, that energy-importing countries would turn to<br />

the more climate-friendly natural gas. But, with export projects facing long delays,<br />

coal could bridge the gap in the market.<br />

The price competitiveness of coal also poses a threat to the development of<br />

renewable energy (RE) sources in <strong>2013</strong> and beyond. If coal is cheaper and the gas<br />

price remains high outside North America, electric utilities will ask themselves:<br />

why convert to RE?<br />

Governments could artificially depress the price of RE to make it attractive to<br />

Atlantic LNG tank (courtesy bptt)

Energy<br />

the consumer, but at a time of constrained budgets everywhere, this is hardly an<br />

appealing strategy.<br />

issues<br />

One energy concern has now been taken off the table and will no longer be<br />

exercising the energy planners’ minds in <strong>2013</strong> and beyond – peak oil. The day<br />

when oil production reach its zenith and starts to decline has now been pushed<br />

well into the future – and may not occur at all, because new sources of fossil fuel<br />

energy are coming into the picture to add to existing oil output.<br />

These are the “unconventional” fuels – shale oil, shale gas, tar sands, coal<br />

bed methane, biofuels – that are being retrieved in greater quantities and will<br />

replace (and probably add to) conventional production from existing geological<br />

structures.<br />

If coal is cheaper and the gas price remains high<br />

outside<br />

Compani<br />

North America, electric utilities will ask themselves:<br />

why convert to renewables?<br />

Countries<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

5

caricom energy policy 1<br />

Energy<br />

issues<br />

The <strong>Caribbean</strong>’s<br />

nightmare import bill<br />

Except for Trinidad and Tobago,<br />

the countries of Caricom have<br />

long faced the acute problem<br />

of having to import the energy<br />

they need for their economies<br />

to function.<br />

This dependence has been worsening.<br />

“The total cost of the annual fuel import<br />

bill for the region today is around (US)<br />

$8-9 billion,” says Desiree Field-Ridley,<br />

officer in charge of trade and economic<br />

integration at the Caricom secretariat in<br />

Guyana, “with the tendency to be rising.”<br />

Compare that with $2.5 billion in<br />

2006, when the Caricom task force,<br />

appointed three years earlier with a<br />

mandate to “develop mechanisms for<br />

a regional energy policy,” was finalising<br />

its draft report. The magnitude of the<br />

dependence is staggering.<br />

With so much foreign exchange<br />

going to pay for one product, however<br />

essential, there is a “deleterious effect”,<br />

as Field-Ridley puts it, “on the economic<br />

and social development of the net<br />

Traffic in St. John’s, Antigua (courtesy Hugh Fiske/Flickr)<br />

energy-importing countries of Caricom.”<br />

The effort made by Venezuela in 2005<br />

to ease that “deleterious effect” through<br />

the PetroCaribe oil supply programme<br />

only plunged the 13 Caricom states<br />

who signed up for it further into debt<br />

and did little to ease their foreign<br />

exchange liability, according to Field-<br />

Ridley’s figures. After a down-payment<br />

of part of the commercial price would<br />

be made, buyers would pay the balance<br />

over several years.<br />

Companie<br />

Countries<br />

Caricom’s energy-importing countries<br />

Despite PetroCaribe, when the price<br />

of oil soared to $<strong>14</strong>7 a barrel in 2008,<br />

“were almost at a panic stage”, to<br />

quote Joseph Williams, manager of the<br />

secretariat’s energy unit. The secretariat<br />

responded with a programme named<br />

C-SERMS (Caricom Sustainable Energy<br />

Road Map and Strategy), to help<br />

accelerate the move towards renewable<br />

energy and more efficient usage in<br />

member states.<br />

C-SERMS has now been subsumed<br />

into the Caricom Energy Policy, which<br />

updates and completes the 2007 task<br />

force report. It was adopted by regional<br />

energy ministers at a special Council<br />

for Trade and Economic Development<br />

meeting in Port of Spain on March 1,<br />

<strong>2013</strong>, and was due to go forward to the<br />

Caricom heads of government in July<br />

for formal ratification.<br />

The major petroleum products on<br />

which Caricom depends are residual<br />

fuel oil for power generation (57% of the<br />

total in 2008) and motor gasolene for<br />

transportation (16%). “Other petroleum<br />

products” accounted for 13%.<br />

The larger Caricom states like<br />

Jamaica and Guyana have to divert 40-<br />

60% of their total export earnings to<br />

pay for this lifeline, leaving relatively<br />

little for other imports, including food<br />

and medicines.<br />

As the Caricom Energy Policy points<br />

out, “for the tourism/services-oriented<br />

countries, such as Belize, Grenada,<br />

St Vincent and the Grenadines and<br />

Barbados, petroleum imports range<br />

from 13% to 30% of export earnings.”<br />

When export income falls, as it did in<br />

Grenada in the year under review (2008),<br />

“a higher oil import/foreign exchange<br />

earnings ratio” has to be faced.<br />

In Caricom, Jamaica is most heavily<br />

dependent on imported energy. It<br />

requires crude oil to feed its 36,000 b/d<br />

Petrojam refinery and refined products<br />

to run the various parts of its economy.<br />

In 2008, it imported 16.3 million<br />

barrels of fuel oil for power generation,<br />

and 4.3 million barrels of gasolene<br />

and 3.6 million barrels of diesel for<br />

transportation.<br />

6

Energy<br />

caricom energy policy 2<br />

issues<br />

Is the <strong>Caribbean</strong> serious<br />

about renewable energy?<br />

The principal purpose of<br />

the Caricom Energy Policy<br />

is to reduce substantially<br />

the Community’s historic<br />

dependence on imported<br />

petroleum products.<br />

Once approved by the regional<br />

heads of government, it will provide a<br />

measure of energy security that has not<br />

been possible when the cost of oil can<br />

fluctuate widely overnight and import<br />

needs are decided by the state of the<br />

economy from year to year.<br />

A major source of Caricom’s petroleum<br />

Compani<br />

imports is actually one of its own –<br />

Trinidad and Tobago. But that is small<br />

comfort, since Trinidad and Tobago sells<br />

its refined products at prices related<br />

to international crude benchmarks.<br />

Caricom states do get some relief<br />

from the part-payment they make on<br />

Venezuelan oil, but that too is little<br />

comfort when deliveries fall short, as<br />

they have often tended to do.<br />

Hence the problem: how to adjust<br />

the energy mix so that oil plays a less<br />

burdensome part?<br />

The Caricom Energy Policy settles<br />

unsurprisingly for a multi-pronged<br />

approach, focusing on enhanced<br />

renewable energy alongside efficiency<br />

measures to reduce the amount of<br />

energy needed to create each dollar of<br />

GDP. It lists renewable inputs as solar,<br />

wind, biomass, landfill gas, bio-ethanol,<br />

hydro, geothermal, waste-to-energy,<br />

marine energy (including tidal and<br />

wave), and even hydrogen.<br />

Countries<br />

Even geothermal-fired electricity<br />

Most of those resources are available<br />

domestically and do not involve the<br />

use of precious foreign exchange once<br />

plant and equipment are installed. Their<br />

very presence enhances energy security.<br />

exchanged between two members<br />

could be regarded as a national source.<br />

The Caricom policy document points<br />

out that, though some progress has<br />

been made with renewable energy in<br />

the region, “the overall proportion of<br />

[its] contribution in primary energy<br />

still remains quite low”. The creation<br />

of a “sustainable energy path” will<br />

require “commitments to increasing the<br />

contribution of both RE and EE.”<br />

EE (energy efficiency) may prove<br />

more difficult to adopt than RE<br />

(renewable energy) because it requires<br />

a conscious change in human behaviour.<br />

Governments are urged to make EE a<br />

more attractive exercise through “fiscal<br />

and other incentives”, especially “solarthermal<br />

systems for hot water production<br />

in all sectors” and setting “minimum<br />

efficiency standards that require electric<br />

utilities to decommission inefficient<br />

generation plant and conduct demand<br />

side management programmes.”<br />

The electricity sector is seen as the<br />

main channel for increasing RE,<br />

since renewable sources can “provide<br />

direct replacement for fossil fuels as the<br />

principal source (base-load type) for<br />

generating electricity at the national<br />

level.”<br />

The 2009 C-SERMS initiative (the<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> Sustainable Energy Road Map<br />

and Strategy) will take responsibility for<br />

promoting both RE and EE. It is expected<br />

to set “quantitative targets for sustainable<br />

energy and “provide an implementation<br />

framework, engaging all member states<br />

and actors in the energy sector.”<br />

The Caricom Energy Policy focuses on increasing<br />

renewable energy while simultaneously pursuing<br />

efficiency<br />

Wigton wind farm, Jamaica (courtesy pcj.com)<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

7

Energy<br />

issues<br />

energy security<br />

A price you can’t afford<br />

Energy security is said to be the ultimate goal of the<br />

Caricom Energy Policy (CEP). But what exactly does<br />

that mean?<br />

According to the policy document, it means: “The<br />

availability of, and timely access to, energy resources<br />

of an acceptable quality at competitive prices that are both<br />

affordable for consumers and reasonable for producers and<br />

reflect true final costs for producing and supplying energy.”<br />

There’s a mouthful for you.<br />

In fact, Caricom has always enjoyed energy security, thanks<br />

to Trinidad and Tobago, the only energy exporter in the region.<br />

A spokesman for Petrotrin, whose refinery has traditionally<br />

supplied gasolene, diesel and fuel oil to the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, once<br />

observed to this YEARBOOK: “Refined products from Trinidad<br />

and Tobago have always been essential to the lifeblood of<br />

the region. Refining started in Trinidad in 1911 and we have<br />

always had a tradition of supplying oil to the <strong>Caribbean</strong>. We<br />

have always met our commitments, through good and bad<br />

times. The other islands could always have relied on Trinidad<br />

for oil – even when they did not pay their bills.”<br />

Supplying a scattered archipelago made up of relatively<br />

small markets is no easy task. As the Petrotrin spokesman<br />

pointed out: “Petrotrin is a merchant refiner, meaning that we<br />

buy crude oil, we have some of our own and we make product<br />

and people order it, with required specifications – sulphur is a<br />

certain range, diesel of a cetane number, we will make that for<br />

you. This demands extraordinary flexibility from the refinery.<br />

We respond to specific customer needs.”<br />

That historic security role was ostensibly taken over by<br />

Venezuela when it launched its PetroCaribe programme in<br />

2005. Trinidad and Tobago energy minister Kevin Ramnarine<br />

acknowledged recently that “some security is now being<br />

provided by the Venezuelans”, adding: “But Trinidad and<br />

Tobago still provides significant volumes of fuel to the Caricom<br />

member states.” The reason for that is refinery flexibility, which<br />

Venezuela’s PdVSA has been unable to match on a consistent<br />

basis.<br />

So “availability of and timely access to energy resources”<br />

is not a problem for Caricom. “Competitive prices”, however,<br />

have been a serious challenge in recent years. Soaring oil costs<br />

have hit Caricom companies and households hardest through<br />

the cost of gasolene at the pump (governments have had to<br />

bargain with fuels retailers to keep rises to a minimum) and in<br />

the cost of electricity.<br />

Companie<br />

“The other islands could always have<br />

relied on Trinidad for oil – even when<br />

they did not pay their bills”<br />

Fuel costs represent 40-50% of generation costs, says the<br />

regional utilities body, Carilec. The average regional fuel<br />

cost was $150 per megawatt hour in 2010. This has translated<br />

into crippling electricity bills throughout Caricom, except in<br />

Trinidad and Tobago (see box).<br />

Affordable pricing is thus the big challenge. Carilec itself<br />

has called for “the creation of an enabling environment, both<br />

regulatory and institutional, for the introduction of indigenous<br />

renewable energy into the national energy mix.”<br />

Countries<br />

The CEP comes down heavily on the side of RE. But will that,<br />

at least in its early days, really help to make power costs “more<br />

affordable” for consumers?<br />

Carilec itself has cast doubt on the likelihood of that<br />

happening. The Jamaican public utility restructuring and<br />

regulation consultant, Winston C. Hay, has categorically told<br />

this YEARBOOK: “RE is not the immediate answer to costs.<br />

I believe it ought to be encouraged and governments are<br />

developing incentives for individuals and small companies to<br />

get involved in RE, but, if anything, it will increase the price of<br />

electricity in the short term.”<br />

Caricom electricity prices<br />

Selected countries<br />

(US$ per Kwh, 2012)<br />

Antigua 0.38<br />

St Vincent 0.36<br />

Barbados 0.36<br />

Grenada 0.35<br />

St Kitts/Nevis 0.34<br />

Guyana 0.34<br />

Jamaica 0.32<br />

Trinidad and Tobago 0.06<br />

Source: Energy Dynamics<br />

8

Energy<br />

the future of gas<br />

issues<br />

Regional policy<br />

undervalues gas<br />

Many, perhaps most, of the electric utilities in<br />

Caricom want to switch to natural gas for<br />

power generation instead of the high-priced<br />

diesel and the light and heavy fuel oil they<br />

Energy Policy (CEP) does not appear to grasp the significance<br />

of that.<br />

In a document meant to outline the energy path that<br />

regional states are expected to travel in the coming decades,<br />

only perfunctory mention is made of gas.<br />

True, the policy does encourage member states to<br />

“implement programmes and projects which aim to<br />

incorporate and optimise the use of natural gas in the energy<br />

mix” and to “establish natural gas as a key energy transitional<br />

have traditionally used. But the Caricom<br />

Compani<br />

source for the region”. But it fails to note the fact that specific<br />

gas-supply investments are already going ahead.<br />

These are, of course, the Eastern <strong>Caribbean</strong> gas pipeline,<br />

which will take gas from Trinidad and Tobago to Barbados,<br />

and the small LNG plant proposed for La Brea in southwest<br />

Trinidad.<br />

Compressed natural gas is touted as another gas source for<br />

Caricom, but the CEP appears much more enthusiastic about<br />

renewable energy, and urges the adoption of “geothermal,<br />

hydro, bio-fuels, solar power, wind power and waste-toenergy,<br />

which can provide direct replacement for fossil fuels as<br />

the principal source (base load type) for generating electricity<br />

at the national level and can support regional, or cross-border,<br />

supply of electricity.”<br />

That last reference is to Nevis and Dominica, which have<br />

plans for developing geothermal power and exporting<br />

it by undersea cable to neighbouring territories. It is also a<br />

reminder of Guyana’s long-held desire to use its large rivers<br />

for hydro-electricity and to export surplus power to the island<br />

archipelago.<br />

As the CEP points out: “Cross-border transmission of<br />

electricity can facilitate a paradigm shift where more member<br />

states can become exporters of energy” – rather than<br />

just Trinidad and Tobago with its existing trade in refined<br />

petroleum products, and regional gas delivery to come.<br />

Trinidad and Tobago might justly feel aggrieved that the<br />

gas it is prepared to offer its fellow Caricom members as an<br />

alternative to oil has been so casually treated in the CEP.<br />

Countries<br />

According to the St Lucia-based <strong>Caribbean</strong> Electric Utility<br />

Services Corporation (Carilec), the regional “trade union” for<br />

the power sector, only 5% of primary energy consumption is<br />

derived from natural gas, with 2% from RE, with oil accounting<br />

for the remaining 93%.<br />

Gas evangelists urge governments to increase that 5%<br />

rather than to undertake the complex and expensive<br />

exercise of creating geothermal and hydro-electric facilities, at<br />

least in the short term.<br />

Indeed, the 2010 Nexant study for the World Bank on<br />

“Regional Energy Solutions for Power Generation in the<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong>” recommended gas more often than RE as part of<br />

the strategy to reduce energy costs up to 2028.<br />

Gas was identified as the main substitute energy source for<br />

oil for Barbados, Jamaica, St Lucia, the Dominican Republic and<br />

Haiti. With specific reference to the <strong>Caribbean</strong> gas pipeline,<br />

Nexant said it would be a “highly economic” investment for<br />

Barbados “if it displaces heavy fuel oil and diesel”, as it will.<br />

Barbados’s own National Energy Policy (2007) envisaged<br />

that 70% of its power would be generated by natural gas by<br />

2030, with only 10% from oil and 20% from RE. The country<br />

will need about 46 mmcfd of gas to achieve this goal, which<br />

suggests it may be in line for LNG as well as pipeline gas.<br />

While natural gas is guilty of higher greenhouse gas<br />

emissions than RE, they are still far lower than oil’s. CO 2 releases<br />

from natural gas are 117,000 pounds per billion British thermal<br />

units of energy input, while those of oil are 164,000. The figure<br />

for coal, by comparison, is 208,000 pounds.<br />

Natural gas releases 92 pounds of nitrogen oxide per billion<br />

btu of energy input, compared with 448 for oil, and one pound<br />

of sulphur dioxide compared with 1,122 pounds from oil.<br />

Potential gas demand<br />

Power generation capacity (peak demand) in line<br />

for conversion to gas<br />

Antigua<br />

Bahamas<br />

Grenada<br />

Guyana<br />

Jamaica<br />

St Lucia<br />

St Vincent<br />

Suriname<br />

Source: <strong>Caribbean</strong> Energy Policy, <strong>2013</strong><br />

51MW<br />

308MW<br />

30.5 MW<br />

94MW<br />

644 MW<br />

55.9 MW<br />

24.5 MW<br />

<strong>14</strong>5 MW<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

9

caribbean gas market<br />

Energy<br />

issues<br />

TT must get moving<br />

Is Trinidad and Tobago moving fast<br />

enough to secure the emerging<br />

market for natural gas in the<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong>? Many energy analysts<br />

think not.<br />

At the time of writing, Gasfin<br />

Development SA, the Luxembourgbased<br />

company leading the way in<br />

trying to push the country into making<br />

sales contracts with <strong>Caribbean</strong> electricity<br />

utilities, had still not been able to line<br />

up an assured gas supply with which to<br />

approach potential customers.<br />

Only about 70 million cubic feet a day<br />

(mmcfd) is required for the first train of<br />

about 500,000 tonnes a year that Gasfin<br />

would like to see sited at the Labidco<br />

industrial estate at La Brea to liquefy gas<br />

for regional export. Perhaps frustrated<br />

by Trinidad and Tobago’s apparent<br />

slothfulness, Gasfin’s CEO Roland Fisher<br />

has hedged his bets by also seeking<br />

permission from the US Department<br />

of Energy to export low-priced shale<br />

gas from a plant he wants to build in<br />

Louisiana.<br />

He was quickly given the green light,<br />

though he now has to clear his 1.5<br />

million tonne per year complex, which<br />

he wants to build in phases, with the<br />

Albert G. Nahas (courtesy Cheniere)<br />

Companie<br />

2020, so Trinidad and Tobago still has the<br />

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.<br />

Gasfin does not expect to be ready to<br />

export LNG from the US much before<br />

opportunity to get in first and capture<br />

the market before Gasfin Development<br />

USA decides to target that customer<br />

base.<br />

One piece of luck for the La Brea<br />

project, which Fisher is calling Project<br />

Constantine, is that his US company, at<br />

least for now, will be permitted to export<br />

only to countries with which the US has<br />

a free trade agreement. Puerto Rico and<br />

the US Virgin Islands (which are part<br />

of the US anyway) and the Dominican<br />

Republic are the only parts of the insular<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> that qualify, so Fisher will be<br />

limited to seeking markets there.<br />

Countries<br />

This leaves 21 other potential markets<br />

in the <strong>Caribbean</strong> archipelago to which<br />

La Brea LNG could theoretically sell gas.<br />

Even Guyana, Suriname and French<br />

Guiana, the first two of which are<br />

members of Caricom, could be potential<br />

targets.<br />

Gasfin Development USA is not the<br />

only company gunning for the <strong>Caribbean</strong><br />

market: Pacific Rubiales in Colombia<br />

is also planning a small LNG export<br />

project. As a competitor, Colombia is an<br />

unknown quantity.<br />

But even if Fisher chose not to try and<br />

sell in the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, and others such<br />

as Cheniere did, Trinidad and Tobago<br />

might very well hold its own. Albert<br />

G. Nahas, Cheniere’s vice president<br />

for international government affairs,<br />

believes that “Trinidad and Tobago is<br />

perfectly capable of competing in the<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> gas market. After all, gas will<br />

still be cheaper in TT than in most of the<br />

rest of the world, except the US.” Fisher<br />

himself has told this YEARBOOK that<br />

he would prefer to supply <strong>Caribbean</strong><br />

markets that materialise from Trinidad<br />

and Tobago rather than the US.<br />

La Brea LNG will open markets near<br />

to home for Trinidad and Tobago<br />

LNG. But it could also present the<br />

country with a unique value-chain<br />

opportunity through the National<br />

Gas Company or its subsidiary, the<br />

National Energy Corporation, not<br />

only in the LNG train itself but in the<br />

ships needed to transport the gas<br />

and the re-gasification facilities at the<br />

receiving end.<br />

At the moment, NGC holds a 10%<br />

share in Atlantic’s train one and 11.1%<br />

in train four, which gives it a quota<br />

of 88 mmcfd. Until recently, this was<br />

sold internationally on its behalf. It has<br />

recently taken back 30 mmcfd to market<br />

on its own account, thus giving it some<br />

experience in these matters prior to any<br />

involvement in La Brea LNG.<br />

Gasfin has been working closely<br />

with EdF, the electricity company in<br />

Martinique and Guadeloupe, with a<br />

view to supplying 200,000 tonnes of<br />

LNG to each French department to run<br />

the gas turbines both are installing.<br />

This would provide a market for 80%<br />

of the capacity of La Brea train one, but<br />

no deal can be struck until a gas supply<br />

from NGC is pinned down.<br />

Roland Fisher (courtesy Gasfin)<br />

10

Energy<br />

issues<br />

the green agenda<br />

It will take a long time to<br />

replace fossil fuels<br />

The “green energy movement”<br />

is slowly gaining momentum<br />

in the <strong>Caribbean</strong>, reflected<br />

for renewable energy and<br />

efficient use of fossil fuel energy. These<br />

initiatives are dealt with elsewhere in<br />

this YEARBOOK, in the context of the<br />

Caricom Energy Policy.<br />

But it’s going to be a hard slog. Oil<br />

will not willingly surrender its position<br />

in the growing enthusiasm<br />

Compani<br />

as the region’s leading energy source.<br />

The International Energy Agency<br />

(IEA), which looks after the interests<br />

of western industrialised countries,<br />

predicts that fossil fuels “will still<br />

account for 80-85% of overall world<br />

energy consumption by 2030.” And<br />

coal, the least green<br />

fossil fuel, is making<br />

something of a<br />

comeback, and could<br />

even reach energy use<br />

parity with oil before<br />

the end of the present<br />

decade.<br />

Gas, the least emissions-intensive<br />

of the three, makes the strongest<br />

claim. Even the Caricom Energy<br />

Policy acknowledges that “compared<br />

with crude oil, natural gas is a less<br />

expensive and cleaner fossil fuel which<br />

can be used not only to generate<br />

electricity efficiently, by deploying<br />

advanced technologies, but also<br />

as a feedstock for the manufacture<br />

of petrochemical products, fuel for<br />

the manufacturing sector and for<br />

vehicular transportation.”<br />

Countries<br />

The policy document urges Caricom<br />

members to “satisfy their demand<br />

for natural gas from the resources<br />

Roger Salloum (courtesy Green Building Council)<br />

“Fossil fuels will still account for 80-85% of<br />

overall world energy consumption<br />

in 2030”<br />

of those member states with such<br />

resources.” The only Caricom state<br />

with exportable gas resources,<br />

Trinidad and Tobago, can take that<br />

as an endorsement of its role in the<br />

emerging Caricom market for LNG<br />

and possibly CNG, and rejection of<br />

the deals US exporters will want to do<br />

with Caricom customers.<br />

With significant take-up of RE some<br />

decades away, most energy analysts<br />

see natural gas as a “bridging fuel”<br />

between oil era and RE.<br />

Other initiatives to move the “green<br />

agenda” forward are slowly<br />

taking shape. Trinidad and Tobago, a<br />

late convert to energy sustainability,<br />

even has a Green Building Council,<br />

established in September 2010, to<br />

preach the virtues of green buildings.<br />

The Council’s president, Roger Salloum,<br />

says its mission is to “transform the way<br />

Trinidad and Tobago’s buildings are<br />

built and communities are designed,<br />

built and operated.”<br />

Salloum claims that “green buildings<br />

can increase worker productivity” by<br />

being “more comfortable and healthier<br />

for the occupants, as compared with<br />

conventionally constructed and<br />

maintained buildings.” Greening,<br />

he suggests, includes a range of<br />

very simple practical steps such as<br />

installing energy-saving<br />

bulbs, recycling plastics<br />

and other materials, and<br />

collecting rain water<br />

for wetting plants and<br />

flushing toilets.<br />

The energy ministry<br />

in Port of Spain wants<br />

citizens to set airconditioning<br />

units a few degrees<br />

warmer, turn off electronic devices<br />

when not in use, and unplug<br />

bedside lamps, TV sets, video games,<br />

computers etc. until they are needed.<br />

Thirteen years ago, Trinidad<br />

and Tobago established a Green<br />

Fund, financed through an annual<br />

tax of 0.1% on gross company<br />

sales. It now has well over TT$2.5<br />

billion available. NGOs and other<br />

groups (but not corporations) that<br />

promote “reforestation, remediation,<br />

environmental education and public<br />

awareness of environmental issues”<br />

can apply to it for assistance.<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

11

Energy<br />

issues<br />

going international<br />

Can state energy companies<br />

make the grade?<br />

Almost every famous name in the energy business<br />

has been involved in Trinidad and Tobago’s<br />

energy sector at one time or another. Yet, despite<br />

105 years of commercial production, no local<br />

company has ever gone abroad to invest in oil or<br />

gas exploration and production.<br />

There was a very short-lived alliance between Petrotrin<br />

and Venezuela’s Inelectra in the early 2000s for exploration<br />

in the Gulf of Paria East block. Petrotrin even set up a special<br />

subsidiary, Petrotrin de Venezolana, for the purpose. But after<br />

one well had been drilled, the arrangement was aborted.<br />

Petrotrin toyed with the idea of investing in the Cuban oil<br />

sector at one point, but that never went very far either.<br />

It’s not hard to guess why the many companies formed<br />

locally to dabble in domestic upstream activity never<br />

considered going overseas. Most of them didn’t last very long,<br />

and none had the financial muscle, even in the <strong>Caribbean</strong>.<br />

But times and attitudes have changed. The local company<br />

Trinity Exploration and Production, armed with US$90 million<br />

of shareholders’ funds from a listing in London early in <strong>2013</strong>,<br />

is mulling the possibility of investing in oil and gas activity<br />

outside Trinidad and Tobago.<br />

But the real thrust in this direction is coming from the<br />

energy ministry itself, which is anxious for state-owned firms<br />

in the energy sector, having demonstrated that they can<br />

perform competently at home, to spread their wings abroad.<br />

The companies involved are:<br />

• NGC (National Gas Company: gas trader, pipeline operator,<br />

LNG exporter)<br />

• Petrotrin (the Petroleum Company of Trinidad and<br />

Tobago: oil and gas producer, refiner)<br />

• NP (the National Petroleum Marketing Company: bunkerer,<br />

refined fuels wholesaler/retailer)<br />

• PPGPL (Phoenix Park Gas Processors: gas liquids extractor/<br />

marketer).<br />

The first three are fully owned by the government: the last<br />

is 51% owned by NGC.<br />

The major role in this international outreach has been<br />

assigned to the NGC, probably the most profitable<br />

domestically-owned firm in Caricom, public or private. Its<br />

turnover was TT$19 billion in fiscal year 2011, TT$5 billion<br />

more than the year before. Its after-tax profit was TT$4.6<br />

Companie<br />

billion, compared with TT$2 billion in 2010.<br />

Energy minister Kevin Ramnarine has pinned his faith on<br />

NGC to an extraordinary degree. He sees it “becoming to<br />

Trinidad and Tobago what Petrobras is to Brazil or Petronas<br />

to Malaysia. Petrobras is almost as powerful in Brazil as the<br />

Brazilian government. There is also the wonderful story of<br />

state company Ecopetrol in Colombia. It was worth a couple<br />

of billion dollars a few years ago and now is being quoted at<br />

over US$100 billion, creating tremendous value for the people<br />

of Colombia, who are its shareholders.”<br />

NGC’s successful foray abroad is therefore essential to<br />

the minister’s grand vision. It has been mandated to “look<br />

at investment opportunities around the world” in order to<br />

expand.<br />

Countries<br />

West and East Africa, where there have been several major<br />

oil and gas discoveries in recent years, is particularly<br />

in the frame. “We are keen on establishing an investment<br />

portfolio in Africa through the vehicle of the NGC,” says<br />

the minister, noting that “natural gas has the potential for<br />

eradicating poverty in East Africa through the provision of<br />

cheap electricity to the populations in Tanzania, Kenya and<br />

Mozambique. These are just some of the possibilities as we<br />

seek to internationalise the Trinidad and Tobago energy<br />

model.”<br />

In its African initiatives, NGC has worked closely with PPGPL,<br />

the specialist in gas liquids extraction and marketing, a likely<br />

activity for state investment in Africa.<br />

PPGPL has already initialled a memorandum of<br />

understanding with the Tanzania Petroleum Development<br />

Corporation for “technical and expert services” in conjunction<br />

with a 500 km pipeline being built by the Chinese Petroleum<br />

Development Services to take gas from discoveries offshore<br />

southern Tanzania to the capital, Dar es Salaam.<br />

PPGPL’s president Eugene Tiah confirms that “there are lots<br />

of opportunities in Africa, but you have aggressive countries<br />

like China that are not waiting around. If we don’t take<br />

advantage of the opportunities, they will be gone soon.”<br />

Nearer to home, Central America is seen as a fruitful area<br />

for state energy company outreach, particularly Panama,<br />

with whom an MOU was signed in March 2012. Potential<br />

avenues for Trinidad and Tobago state company investment<br />

there include bunkering facilities (Petrotrin), a blending plant<br />

and refined products retailing (NP), and gas-based industries<br />

(NGC/PPGPL).<br />

12

Energy<br />

alternative fuels<br />

issues<br />

Fuel switching is not<br />

catching on<br />

Only Trinidad and Tobago,<br />

and to some extent<br />

Jamaica, which has<br />

experimented with an<br />

the pump, are showing any interest in<br />

alternatives to gasolene and diesel as<br />

transportation fuels. But the <strong>Caribbean</strong><br />

Energy Policy (CEP) devotes a whole<br />

chapter to the subject.<br />

This means that the adoption of<br />

non-traditional fuels for transport is<br />

now an imperative to which Caricom’s<br />

15 member nations will have to adhere<br />

E10 (ethanol) mixture at<br />

Compani<br />

(though the CEP is not a mandatory<br />

guideline, only voluntary).<br />

“Fuel switching”, as the CEP<br />

describes it, is designed to encourage<br />

the use of “cleaner energy sources and<br />

a more efficient transportation sector.”<br />

Transport is seen as “contributing a<br />

high level of emissions, including<br />

greenhouse gases,” thus making it “a<br />

serious environmental matter” in the<br />

eyes of the CEP.<br />

Transport in Caricom is also “highly<br />

vulnerable to dependence on imported<br />

fuel supplies and unpredictable spikes<br />

in oil prices.” So, not surprisingly,<br />

the CEP recommends greater use of<br />

compressed natural gas and biofuels<br />

like ethanol and bio-diesel, as well as<br />

“electric and hybrid vehicles.”<br />

Trinidad and Tobago has about<br />

4,500 vehicles equipped with CNG<br />

(out of some 650,000 registered). A few<br />

hybrids have been imported by motor<br />

vehicle dealers, including one for the<br />

ministry of energy, to boost “energy<br />

efficiency awareness among the<br />

driving population”. It is not clear how<br />

many motorists in Jamaica have opted<br />

for E10, but it can’t be very many.<br />

Countries<br />

In other words, the adoption of nonconventional<br />

transport fuels has a very<br />

long way to go in Caricom.<br />

While Trinidad and Tobago is not<br />

dependent on imported fuel<br />

supplies, the driver for fuel switching is<br />

the need to reduce the use of gasolene<br />

and diesel and cut the government<br />

subsidy on the price of these fuels at the<br />

pump, which is costing several billion<br />

TT dollars a year. The energy ministry is<br />

still seeking a way of enticing motorists<br />

to add CNG capability to their vehicles.<br />

One approach under consideration is to<br />

fund the cost in whole or in part.<br />

CNG has some advantages, but it<br />

also has some disincentives, as even the<br />

ministry concedes. The vehicle becomes<br />

heavier, it loses trunk space to the CNG<br />

cylinders, the system has to be inspected<br />

annually (instead of every three years<br />

for gasolene and diesel vehicles over a<br />

certain age), stricter safety measures are<br />

applied, engine power is reduced 5-10%<br />

by conversion, and range falls to 200-<br />

250 km compared with 400-550 km for<br />

gasolene/diesel vehicles.<br />

With such an array of negatives, it is<br />

perhaps unsurprising that CNG had<br />

not enjoyed the take-up the ministry<br />

would like to see. If and when natural<br />

gas deliveries finally arrive in the rest<br />

of Caricom, the same hesitation will<br />

presumably be seen.<br />

Hybrid car donated to the Ministry of Energy<br />

It is hard to predict whether electricity<br />

would fare any better. Purely electric<br />

vehicles are not on the immediate<br />

horizon for Caricom, since charging<br />

points are unlikely to be available for<br />

a long time.<br />

The halfway house is the hybrid<br />

vehicle, powered by gasolene or<br />

diesel but equipped with a battery<br />

which does not need a recharging<br />

station. “The motion of the wheels<br />

as the car moves charges a battery,”<br />

minister Ramnarine explains, “and at<br />

the opportune time, when the battery<br />

is charged, the vehicle switches to the<br />

battery.”<br />

Another unconventional fuel source<br />

is methanol, made from natural gas<br />

blended with gasolene or diesel, or<br />

even used on its own.<br />

An experiment in 2011, involving<br />

Petrotrin and Trinidad and Tobago’s<br />

two methanol giants, Methanol<br />

Holdings and Methanex, was said<br />

to have produced “encouraging”<br />

results. But the initiative was not<br />

taken any further by Petrotrin, whose<br />

participation in any long-term addition<br />

of methanol to gasolene is essential for<br />

any real progress to be made.<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

13

TT oil revival 1<br />

Energy<br />

issues<br />

After three decades of<br />

decline ...<br />

Trinidad and Tobago’s<br />

petroleum liquids production<br />

peaked at 229,589 barrels<br />

a day (b/d) in 1978, almost<br />

all of it crude oil. By 2012 it<br />

had fallen to 81,735 b/d, of which crude<br />

represented 69,062 b/d (the rest was<br />

condensate). The loss of 160,527 b/d<br />

over 34 years translates into billions<br />

of dollars of lost foreign exchange<br />

earnings and government revenue.<br />

A former minister of energy, Senator<br />

Conrad Enill, once suggested that<br />

80,000 b/d of crude output should set<br />

alarm bells ringing. He could hardly<br />

have envisaged how quickly that<br />

scenario would come to pass and how<br />

much worse it might get.<br />

What has saved the day, to some<br />

extent, is the fact that oil prices have<br />

held up remarkably well in the last few<br />

years, at $90-100 a barrel: even with a<br />

staggering drop in production, oil sales<br />

still provide the Trinidad and Tobago<br />

treasury with 55% of its revenue from<br />

hydrocarbons. Gas yields 45%, despite<br />

the fact that it out-produces oil by a<br />

factor of seven in terms of barrels of oil<br />

equivalent.<br />

Finance minister Larry Howai pegged<br />

his oil tax inflows for the 2012-3 fiscal<br />

year at $75 a barrel and gas at $2.75<br />

per mmbtu netted back to Trinidad and<br />

Tobago.<br />

One reason for the headlong decline<br />

in crude retrieval is the fact that<br />

older reservoirs (which means most of<br />

them) are delivering 8-10% less every<br />

year (Petrotrin’s land fields and the<br />

Repsol-Petrotrin-NGC Teak/Samaan/<br />

Poui block off the east coast are prime<br />

examples).<br />

Other reasons are the fall of 12,726<br />

b/d in production from Trinmar,<br />

Companie<br />

Petrotrin’s Gulf of Paria unit, between<br />

2004 and 2010, and the failure of<br />

the Kairi and Canteen oil discoveries,<br />

operated by BHP Billiton T&T in block<br />

2c off Trinidad’s north east coast, to<br />

live up to expectations. The latter was<br />

producing 50,542 b/d on average a few<br />

months after start-up in 2005, but had<br />

dwindled to 12,479 b/d by 2012.<br />

A further factor in this unsettling<br />

decline situation has been the inability<br />

of companies signing production<br />

sharing contracts with the energy<br />

ministry in the last 20 years to find<br />

new oil resources. Out of 36 such<br />

agreements, only two – yes, two –<br />

resulted in discoveries of crude, both<br />

Countries<br />

of them by BHP Billiton T&T and its<br />

partners, in block 2c (see above) and in<br />

block 3a, where no development has<br />

yet begun.<br />

The development of block 2c and<br />

the fact that Trinmar has held relatively<br />

steady in the last three years means<br />

that crude production still comes<br />

primarily from offshore – about 47,519<br />

Galeota platform (courtesy Petrotrin)<br />

b/d in 2012, compared with 21,543 b/d<br />

from onshore.<br />

In his first public address after<br />

becoming energy minister in 2011,<br />

Senator Kevin Ramnarine declared<br />

that the “number one priority” of his<br />

stewardship (which ends in May 2015)<br />

was to “increase national oil production.”<br />

At the time of writing, he had not<br />

achieved much success in that regard.<br />

But he remains optimistic, predicting<br />

“a major increase in oil production<br />

around the period May/June <strong>2013</strong>.”<br />

By February <strong>2013</strong>, according to the<br />

latest data available, there had been<br />

only a very marginal improvement:<br />

the average 69,163 b/d of crude being<br />

lifted that month was 101 b/d above<br />

the 2012 average.<br />

It remains to be seen what will<br />

happen during the rest of <strong>2013</strong>. The<br />

following story in this YEARBOOK<br />

recounts what is being done, and what<br />

can still be done, to achieve a muchdesired<br />

turnaround.<br />

<strong>14</strong>

Energy<br />

tt oil revival 2<br />

issues<br />

How to increase oil<br />

production<br />

What is the key to reviving crude oil production<br />

in Trinidad and Tobago, which, as already<br />

noted, has crashed from 229,589 b/d 34<br />

years ago to 69,062 b/d today?<br />

But there have been precious few of those by companies<br />

working under the current system of production-sharing<br />

contracts (PSCs).<br />

Companies operating under the older exploration and<br />

production (E&P) licences have been a little more successful.<br />

Bayfield Energy (now absorbed by Trinity Exploration and<br />

Production) has identified what it said were about 32 million<br />

barrels of recoverable oil with its FG8 exploratory well in the<br />

Galeota block off southeast Trinidad, while Petrotrin found<br />

The obvious answer is new discoveries.<br />

Compani<br />

about 48 million barrels of “new hydrocarbon potential” in<br />

the course of a five-well exploration programme in the East<br />

Soldado area, subsequently named Jubilee in honour of the<br />

50th anniversary of the country’s independence. Both finds<br />

were made in 2012. Some new oil was also discovered in the<br />

Cory Moruga block on land in 2010.<br />

Further discoveries may be made in the course of the<br />

extensive exploratory drilling due to take place in the course<br />

of <strong>2013</strong>: among others, by Trinity in the Point Ligoure, Guapo<br />

Bay, Brighton Marine (PGB) block in the Gulf of Paria, and in<br />

the Galeota block; by Niko in the Mayaro/Guayaguayare block,<br />

which runs from the onshore to the offshore in south Trinidad;<br />

and by Parex Resources in the Central Range Shallow and<br />

Deep blocks on land.<br />

Under renewed E&P licences, Petrotrin has to drill four<br />

exploratory wells for Trinmar and two in the North Marine<br />

block. Following the interpretation of its 2012 3D seismic<br />

survey, it will also be doing exploratory drilling on land in late<br />

<strong>2013</strong> and beyond.<br />

Exploratory drilling is risky and results can not be guaranteed,<br />

but development drilling in an already producing location<br />

is of course much less so and can at least replace reserves.<br />

Trinity plans to sink 12 development wells onshore in <strong>2013</strong>,<br />

and 12 in the Galeota block. Lease operators, farmout<br />

operators and incremental production service contractors will<br />

all be doing similar work.<br />

Energy minister Kevin Ramnarine has put great faith<br />

in Petrotrin as being “at the centre of the strategy for oil<br />

Countries<br />

production”, and Trinmar as “at the centre of that centre.”<br />

Concurrent with its exploratory activities in Trinmar, Petrotrin<br />

is reactivating its South West Soldado field, now producing<br />

The energy ministry says it will<br />

offer three land blocks for<br />

exploration this year<br />

about 6,000 b/d, in the belief that it can be boosted to 8,000<br />

b/d by the end of <strong>2013</strong>. Sixty wells which were capped ten<br />

years ago are being gradually returned to production: a few<br />

are already producing again, and the rest will come on line as<br />

they are worked over by a rig hired for that purpose.<br />

New block allocations are an important part of minister<br />

Ramnarine’s oil revival plan. In conjunction with Petrotrin, the<br />

ministry says it will offer three land blocks for exploration this<br />

year. More deep water and some shallow water blocks are also<br />

carded for allocation before the end of <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

New blocks, and exploratory and development drilling<br />

in existing blocks, are all essential, but many analysts<br />

point out that for decades companies have ignored oil that<br />

is known to exist and which could have contributed long ago<br />

to arresting the production decline – both heavy oil and “leftbehind”<br />

medium-gravity crude in reservoirs that have ceased<br />

to produce, or are producing very little.<br />

Geologist Dr Krishna Persad has estimated that there is<br />

probably well over two billion barrels of crude left behind in<br />

reservoirs where natural pressure or even pumping no longer<br />

works. As for heavy oil, minister Ramnarine suggests there are<br />

“seven billion barrels in places like Trinmar and the southern<br />

basin on land.”<br />

Even if the correct figure is only half that or less, it represents<br />

a vast unexploited resource that could help achieve the<br />

country’s oil restoration goals.<br />

The government has offered incentives over the years to<br />

encourage companies to invest in mature marine and land<br />

fields, via a 20% tax credit, and to use enhanced oil recovery<br />

measures for lifting heavy oil. In the current national budget,<br />

it introduced a special supplemental petroleum tax rate of<br />

25% for the development of small discovered oil pools lying<br />

inactive. Deep horizon drilling both on and offshore was<br />

encouraged with the offer of a 40% uplift on exploration costs.<br />

The deep horizon, like the deep water, could be an entirely<br />

new source of crude which the ministry has been urging<br />

companies to target.<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

15

cross-border gas<br />

Energy<br />

issues<br />

Venezuela lethargy keeps<br />

gas stranded<br />

The cross-border gas straddling the maritime<br />

boundary between Trinidad and Tobago and<br />

Venezuela southeast of Trinidad and northeast of<br />

the Orinoco Delta looks likely to remain out of reach<br />

indefinitely, because the two countries seem unable<br />

to move the commercialisation process forward.<br />

That means that 1.8 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of confirmed gas<br />

reserves in the Manatee discovery in Trinidad and Tobago’s block<br />

6d (which partners the Loran find in Venezuela’s Plataforma<br />

Deltana block 2), and around 1 tcf of gas in the Manakin discovery<br />

in block 5b (linked with Coquina in Plataforma Deltana block 4),<br />

will not be available for use in Trinidad and Tobago’s reviving<br />

downstream gas-based industrial development programme.<br />

Such a waste of badly-needed gas at a time when current<br />

exploitable reserves are almost all committed is clearly<br />

unacceptable.<br />

The problem, as energy analysts see it, is that Venezuela<br />

feels no urgency in developing cross-border gas because it has<br />

dumped plans – for how long, no one knows – to get into the<br />

LNG business.<br />

Its Plataforma Deltana reserves were always destined for<br />

the export trade. Chevron, the operator of block 2, has made<br />

no secret of the fact that under its licence it must provide 90%<br />

of the 6.2 tcf in Loran for use as LNG and the remaining 10%<br />

for domestic use in Venezuela. It has a 39% holding in block 2,<br />

Venezuela’s PdVSA holding the other 61%.<br />

With LNG off the table, the government in Caracas sees<br />

little sense in rushing to commercialise the gas. The 10% that<br />

was destined for domestic use can be sourced from other gas<br />

discoveries closer to the mainland, such as the very large one<br />

that Repsol made in the Gulf of Venezuela recently, or even the<br />

proven reserves in the Paria Norte region.<br />

Trinidad and Tobago’s energy minister Kevin Ramnarine<br />

could scarcely conceal his impatience when he last spoke<br />

publicly about the cross-border gas matter. In an address at<br />

the Austin Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of<br />

Commercialisation has long been<br />

under way with the development of<br />

Kapok<br />

Companie<br />

“It is very hard to get the Venezuelans<br />

to meet with us on this issue”<br />

Texas in Austin in March <strong>2013</strong>, he said: “It is very hard to get the<br />

Venezuelans to meet with us on this issue.”<br />

He noted that he had “been in contact with minister Rafael<br />

Ramírez” (who has been retained as minister of energy and<br />

petroleum in the new Maduro government) and had also<br />

“spoken with Chevron” (the operator of both Manatee and<br />

Loran), but did not seem to hold out much hope for crossborder<br />

monetisation any time soon.<br />

The project appears to be stuck at the stage of selecting a<br />

unit operator. A unit directing committee representing all the<br />

stakeholders in the matter – the two energy ministries, Chevron,<br />

Countries<br />

the BG Group and PdVSA – was supposed to select the operator<br />

early last year, but the Venezuelans failed to turn up in Port of<br />

Spain for the scheduled technical meeting.<br />

Then President Chávez’s lengthy illness and death, and the<br />

election of Nicolás Maduro Moros as his successor, put a stop to<br />

decision-making in Caracas on matters like cross-border gas for<br />

most of 2012; and the post-electoral situation does not seem to<br />

have changed anything.<br />

As far as the Manakin (BP/Repsol) and Coquina (Statoil/<br />

PdVSA) discoveries are concerned, no unitisation<br />

agreement has been signed. The reservoir joint working group,<br />

comprising officials from both sides, has identified the total<br />

volume of gas reserves they believe to be there. But the specific<br />

amount on each side has not yet been determined. A “best<br />

guess” estimate is about 1 tcf in each discovery.<br />

The situation in the third pair of cross-border gas blocks<br />

– bpTT’s Kapok discovery on the Trinidad side and the<br />

Dorado find by PdVSA in block 1 in Venezuela – is different,<br />

in that commercialisation has long been under way with the<br />

development of Kapok. The estimated combined reserves in<br />

the two blocks is about 1 tcf, and PdVSA has allowed bpTT to<br />

produce what it can from the two reservoirs.<br />

When the exact amount on each side is determined, if<br />

production from the Kapok field has exceeded the allocated<br />

reserves allocated, bpTT would agree on some form of<br />

compensation for PdVSA.<br />

16

Energy<br />

issues<br />

Deep water exploration<br />

The last real frontier?<br />

Deep geological horizons on land and offshore<br />

are a possible new oil and gas play in Trinidad<br />

and Tobago (and received incentives in the<br />

2012-<strong>2013</strong> national budget), but the real last<br />

The ministry has bent over backwards<br />

to make deep water activity<br />

economically attractive, which it has<br />

not been in the past<br />

frontier for substantial hydrocarbon discovery<br />

Compani<br />

is exploration in deep water, at whatever geological depth.<br />

Deep water is defined by the energy ministry in Port of<br />

Spain as a water depth of 1,000 metres and more.<br />

No exploration beyond about 1,500 metres has actually<br />

taken place before. Eight wells were sunk in the continental<br />

slope in the late 1990s and early 2000s in water depths of<br />

750-1,500 metres, but only one find of non-commercial<br />

gas was made.<br />

In 2012, the BP Group signed two production-sharing<br />

contracts for exploring in the Atlantic deep water off the<br />

east coast. Water depth in the two blocks, 23a and TTDAA<br />

<strong>14</strong>, is around 2,000 metres.<br />

BP is leading the first assault on real deep water acreage<br />

in Trinidad and Tobago. It will be followed by BHP Billiton,<br />

which was awarded four other blocks – TTDAA 5-6 and<br />

TTDAA 28-9 – in the subsequent bid round (see map on<br />

p26-27).<br />

Deep horizon exploration, on land or offshore, could<br />

itself result in the identification of a new play, if the<br />

incentive offered – a <strong>14</strong>0% write-off on exploration costs<br />

– is enough to entice explorationists. “Deep horizon” has<br />

been defined by the ministry as 8,000 feet or more on land<br />

and 12,000 feet or more offshore.<br />

While he would clearly be pleased with a deep horizon<br />

discovery, Trinidad and Tobago’s energy minister<br />

Kevin Ramnarine is betting on the deep water. He believes<br />

that “both BP and BHP Billiton, two long-established<br />

players in the country, stand poised to take us into a period<br />

of exciting deep water exploration” and that “the deep<br />

water in Trinidad is one of the holy grails of geologists, who<br />

have long suspected its vast hydrocarbon potential.”<br />

This potential has been estimated by the energy<br />

ministry at 4.7-8.2 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas in the two<br />

BP blocks (no estimate has been given publicly for possible<br />

oil resources), and 2.4-23.6 tcf of gas and 428-4,200 million<br />

barrels of oil in BHP Billiton’s four blocks.<br />

The latter would have had its own reasons for bidding<br />

so aggressively on four of the five blocks that attracted<br />

companies’ attention in the 2012 deep water auction, but<br />

the ministry has bent over backwards to make deep water<br />

activity economically attractive, which it has not been in<br />

the past. These attractions are intended to “reduce risk and<br />

offer companies a more competitive environment,” and<br />

include:<br />

• Cost recovery (“cost oil or gas”) increased from 60 to<br />

80%<br />

• A 35% petroleum profits tax and an 18% supplemental<br />

petroleum tax payable on oil only. This allows the<br />

company to claim a higher share of “profit oil or gas”<br />

since the government’s take under the productionsharing<br />

system is based on these two taxes<br />

• A <strong>14</strong>0% write-off for deep water exploratory wells,<br />

further enhancing the companies’ share of “profit oil or<br />

gas”.<br />

Countries<br />

The ministry is following up on its 2010 and 2012 deep<br />

water bid rounds with another in <strong>2013</strong>, which it hopes<br />

will attract new companies into the hydrocarbon sector.<br />

Minister Ramnarine told this YEARBOOK: “companies which<br />

did not bid in 2012 have told us they will bid in <strong>2013</strong> ... In<br />

one case, they told us that they had a restructuring exercise<br />

“BP and BHP Billiton, two long-established<br />

players in the country, stand<br />

poised to take us into a period of<br />

exciting deep water exploration”<br />

going on in 2012, and another said it had quite a lot on<br />

its plate at the time. So, I think that we have stimulated<br />

widespread interest in our deep water bid rounds.”<br />

energycaribbean YEARBOOK <strong>2013</strong>/<strong>14</strong><br />

17

independents<br />

Small and medium-sized<br />

petroleum enterprises in<br />

Trinidad and Tobago, the<br />

“independents”, are expected<br />

to play a key role in the revival<br />

of oil production.<br />

There is no formal definition of an<br />

“independent” in terms of assets or<br />

reserves, though when companies<br />

producing up to 3,500 b/d were<br />

exempted from petroleum production<br />

levy payment nine years ago, this<br />

was generally taken as an indication<br />

of independent status. It’s only a<br />

rough guide, however, because some<br />

“independent” upstreamers are already<br />

close to that level or beyond it.<br />

A more reliable definition of an<br />

independent in the Trinidad and Tobago<br />

context might be an operator which is<br />

not state-owned, and does not belong<br />

to a major international group like BHP<br />

Billiton or Repsol (oil), bpTT, BG T&T or<br />

EOG Resources (condensate).<br />

On that basis, independents were<br />

responsible for about 10,241 b/d of<br />

crude output on average in 2012, out of<br />

69,062 b/d from all companies (another<br />

12,673 b/d was condensate, taking the<br />

liquids total up to 81,735 b/d). Petrotrin’s<br />

contribution was 34,818 b/d (oil) from<br />

its onshore and offshore fields.<br />

Nobody is likely to challenge Petrotrin<br />

in the future, unless some major<br />

discovery of crude is made in deeper<br />

geological horizons or in the deep water.<br />

Petrotrin’s dominance is secure, given<br />

the extent of its acreage compared with<br />

that of the independents.<br />

But 10,241 b/d out of 69,062 b/d<br />

(almost 15%) is a good performance,<br />

when you consider that most of those<br />

companies are lifting crude from wells<br />

Petrotrin itself abandoned or from very<br />

small tracts of farmed-out land.<br />

18<br />

Energy<br />

issues<br />

A key contribution to<br />

oil revival<br />

Independents could be<br />

pioneers in the application<br />

of carbon dioxide<br />

(co2) injection for enhanced<br />

oil recovery<br />

There are about 17 independents<br />

active in the local petroleum sector<br />

today, occupying different niches. Some<br />

are lease operatorships (in 1989 Trintopec<br />

Companie<br />

independent of all, straddles the whole<br />

Countries<br />

handed over idle and low-producing<br />

wells to smaller independent operators<br />

who might do a better job with them).<br />

Others are farm-out operators, who have<br />

obtained larger areas on which to sink<br />

new wells if they want.<br />

Joint venture arrangements involve<br />

whole blocks, where the independent<br />

company is obliged to undertake seismic<br />

surveying and exploration. Incremental<br />

production service contractors are a new<br />

breed invented by Petrotrin in 2009 to<br />

help generate more production from<br />

its southeastern onshore fields, which<br />

had found themselves neglected over<br />

the years. There is also one standalone<br />

independent, Mora Oil Ventures<br />

(Moraven), which only operates<br />

offshore, not on land at all, unlike the<br />

rest of the independent sector.<br />

Trinity, shaping up to be the biggest<br />

spectrum, being simultaneously a lease<br />

operator, farm-out operator and joint<br />

venturer.<br />

All knowledgeable observers of the<br />

Trinidad and Tobago energy scene<br />

expect the independents to enlarge<br />

their contribution to crude production<br />

in the years ahead. Energy minister<br />

Kevin Ramnarine has begun regular<br />

meetings with the sector to hear and try<br />

to resolve its problems.<br />

David Borde, managing director of<br />

PetroCom Technologies, the company<br />

promoting a “smart pumping” system<br />

that could help independents improve<br />

well productivity, sees their role<br />

in oil revival as “absolutely critical”.<br />

Geologist Dr Krishna Persad, a farmout<br />

operator through his company<br />

KPA and Associates, has just acquired<br />

Trinidad Exploration and Development<br />

in southwest Trinidad, and strongly<br />

believes the independents could be<br />

pioneers in the application of carbon<br />

dioxide (CO 2 ) injection for enhanced oil<br />

recovery.<br />

Minister Ramnarine has mandated<br />

the National Gas Company to examine<br />

the feasibility of a CO 2 pipeline from<br />

the Point Lisas industrial estate to the<br />

oilfields of the southern basin.<br />

Trinity Exploration and Production<br />

is aiming for production of 5,000 b/d<br />

by the end of <strong>2013</strong>. Range Resources<br />

is targeting 4,000 b/d, and Touchstone<br />

Exploration 3,300 b/d.<br />

Independents were responsible for about 10,241<br />

b/d of crude output on average in 2012, out of<br />

69,062 b/d from all companies

Energy<br />

climate change<br />

issues<br />

What should the <strong>Caribbean</strong> do?<br />

Caricom’s 15 member nations have pledged to<br />

measure and reduce the level of greenhouse<br />

gas emissions in the region, in keeping with<br />

the Caricom Energy Policy (CEP). Targets will be<br />

influenced by Caricom’s “international obligations<br />

and voluntary commitments under the United Nations<br />

Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Alliance<br />

of Small Island States’ climate change negotiating strategy and<br />

objectives.”<br />

This initiative is part of the agenda of Caricom’s <strong>Caribbean</strong><br />

Sustainable Energy Road Map and Strategy (C-SERMS).<br />

Determining the baselines for greenhouse gas emissions<br />

has become more urgent with global emission levels reaching<br />

their highest point in over two million years. Carbon dioxide<br />

(CO 2 ) emissions, by far the major contributor to global<br />

warming, hit 400 parts per million in May, a jump of 85 ppm<br />

in 55 years.<br />

The world is now pumping 38.2 billion tons of CO 2 into the<br />

Compani<br />

atmosphere every year, China being the worst offender with<br />

10 billion. The United States, the second worst offender, has<br />

actually been lowering its CO 2 discharges, which are now<br />

down to 5.9 billion tons a year. The reasons are said to be the<br />

rapid switch to gas-fired power generation and the growth of<br />

fuel-efficient vehicles.<br />

The 400 ppm reading augurs badly for governments’ goal of<br />

holding the rise in average temperature below two degrees<br />