Patients as Consumers - Harvard Law School

Patients as Consumers - Harvard Law School

Patients as Consumers - Harvard Law School

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

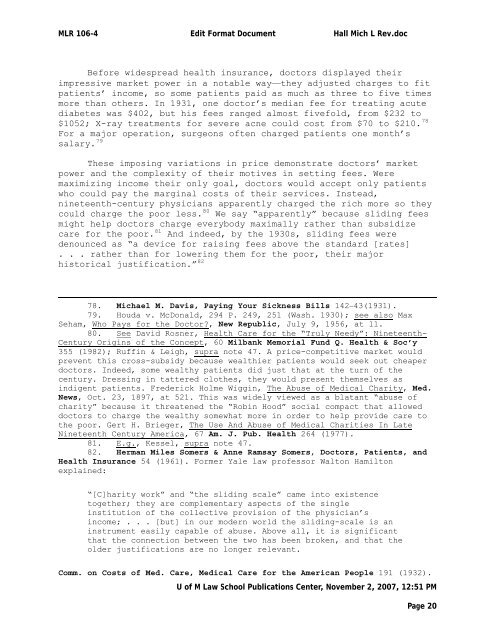

MLR 106-4 Edit Format Document Hall Mich L Rev.doc<br />

Before widespread health insurance, doctors displayed their<br />

impressive market power in a notable way—they adjusted charges to fit<br />

patients’ income, so some patients paid <strong>as</strong> much <strong>as</strong> three to five times<br />

more than others. In 1931, one doctor’s median fee for treating acute<br />

diabetes w<strong>as</strong> $402, but his fees ranged almost fivefold, from $232 to<br />

$1052; X-ray treatments for severe acne could cost from $70 to $210. 78<br />

For a major operation, surgeons often charged patients one month’s<br />

salary. 79<br />

These imposing variations in price demonstrate doctors’ market<br />

power and the complexity of their motives in setting fees. Were<br />

maximizing income their only goal, doctors would accept only patients<br />

who could pay the marginal costs of their services. Instead,<br />

nineteenth-century physicians apparently charged the rich more so they<br />

could charge the poor less. 80 We say “apparently” because sliding fees<br />

might help doctors charge everybody maximally rather than subsidize<br />

care for the poor. 81 And indeed, by the 1930s, sliding fees were<br />

denounced <strong>as</strong> “a device for raising fees above the standard [rates]<br />

. . . rather than for lowering them for the poor, their major<br />

historical justification.” 82<br />

78. Michael M. Davis, Paying Your Sickness Bills 142–43(1931).<br />

79. Houda v. McDonald, 294 P. 249, 251 (W<strong>as</strong>h. 1930); see also Max<br />

Seham, Who Pays for the Doctor?, New Republic, July 9, 1956, at 11.<br />

80. See David Rosner, Health Care for the “Truly Needy”: Nineteenth-<br />

Century Origins of the Concept, 60 Milbank Memorial Fund Q. Health & Soc’y<br />

355 (1982); Ruffin & Leigh, supra note 47. A price-competitive market would<br />

prevent this cross-subsidy because wealthier patients would seek out cheaper<br />

doctors. Indeed, some wealthy patients did just that at the turn of the<br />

century. Dressing in tattered clothes, they would present themselves <strong>as</strong><br />

indigent patients. Frederick Holme Wiggin, The Abuse of Medical Charity, Med.<br />

News, Oct. 23, 1897, at 521. This w<strong>as</strong> widely viewed <strong>as</strong> a blatant “abuse of<br />

charity” because it threatened the “Robin Hood” social compact that allowed<br />

doctors to charge the wealthy somewhat more in order to help provide care to<br />

the poor. Gert H. Brieger, The Use And Abuse of Medical Charities In Late<br />

Nineteenth Century America, 67 Am. J. Pub. Health 264 (1977).<br />

81. E.g., Kessel, supra note 47.<br />

82. Herman Miles Somers & Anne Ramsay Somers, Doctors, <strong>Patients</strong>, and<br />

Health Insurance 54 (1961). Former Yale law professor Walton Hamilton<br />

explained:<br />

“[C]harity work” and “the sliding scale” came into existence<br />

together; they are complementary <strong>as</strong>pects of the single<br />

institution of the collective provision of the physician’s<br />

income; . . . [but] in our modern world the sliding-scale is an<br />

instrument e<strong>as</strong>ily capable of abuse. Above all, it is significant<br />

that the connection between the two h<strong>as</strong> been broken, and that the<br />

older justifications are no longer relevant.<br />

Comm. on Costs of Med. Care, Medical Care for the American People 191 (1932).<br />

U of M <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> Publications Center, November 2, 2007, 12:51 PM<br />

Page 20