Nov 2016

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Choroidal melanoma: a spotter’s guide<br />

BY PETER HADDEN*<br />

There are not many truly life-threatening<br />

ocular conditions, but choroidal melanoma<br />

is certainly one of them. Overall, about 50%<br />

of people diagnosed with it will, in the fullness<br />

of time, die from it, so one can certainly say that<br />

it is something no one wants to miss. Missing it<br />

has been the subject of lawsuits in the USA and,<br />

even in New Zealand, this diagnosis has graced<br />

the adverse comments section of our Health and<br />

Disability Commission, wondering if “x failed to<br />

provide services with reasonable care and skill…”.<br />

Luckily, that happened 16 years ago (before my<br />

time, may I add!), but we certainly don’t want it to<br />

come up again. So how can we avoid that?<br />

Obviously the first step is not to miss the<br />

diagnosis. Unfortunately, although melanoma is<br />

rare, naevi are not and sometimes the differences<br />

can be subtle. Furthermore, the only time when<br />

maybe we might be able to make a difference to<br />

the prognosis, ie. reduce the risk of metastatic<br />

disease in the future, is if we can catch and treat<br />

melanomas when they’re small, which of course is<br />

when they are most easily confused for naevi.<br />

One study found that, for small indeterminate<br />

pigmented tumours, ie. ones that might be<br />

naevi or might be melanoma, there was a 5%<br />

cumulative chance of metastatic death for<br />

each of the following risk factors: margin at the<br />

disc, lipofuscin, symptoms and subretinal fluid.<br />

Therefore if you’ve got all four there’s a 20%<br />

chance you’ll be dead in a few years.<br />

Some bright spark then came up with a<br />

mnemonic to help people remember what to look<br />

for if you think you’ve seen a naevus but don’t<br />

want to miss a small melanoma (small being less<br />

than 2.5mm thick). That mnemonic is “To find<br />

small ocular melanoma”. This stands for thickness,<br />

fluid, symptoms, orange pigment and margin at<br />

the disc. Naturally of course others subsequently<br />

pointed out that this didn’t really cover everything;<br />

ophthalmologists routinely do an ultrasound<br />

(B-scan) on all such lesions and therefore we<br />

routinely add two letters to this, looking for<br />

hypoechogenicity and characteristic shapes (as<br />

well as the thickness, which ultrasound is very<br />

good at measuring). Then of course, documented<br />

growth is another risk factor. Fortunately many<br />

of you probably don’t have ultrasound anyway so<br />

you don’t have to remember those two letters, but<br />

do remember to look at old photos to see if it has<br />

changed.<br />

It might be helpful at this juncture to go over<br />

what each of these “suspicious features” actually<br />

are:<br />

T is for thickness<br />

If it’s more than 2mm thick, that’s a bad sign. This<br />

suspicious feature actually is best appreciated by<br />

ultrasound, since on ultrasound you can measure it<br />

very easily, as previously mentioned. But if you’ve<br />

got OCT, you can switch on “enhanced depth<br />

imaging” (EDI) or push the OCT machine forward<br />

so that the image flips and you can get a pretty<br />

image of the choroid and usually you can measure<br />

the thickness of the tumour on this, but only if it’s<br />

less than about 1mm thick.<br />

F is for fluid<br />

Subretinal fluid is a danger sign. Naevi can often<br />

have a bit of fluid over the top of them, which<br />

doesn’t matter, but if it’s leaking fluid around it,<br />

that’s bad (unless of course it’s from something<br />

else, like a choroidal neovascular membrane, which<br />

you can get with naevi). Often you can see this<br />

around the tumour or, if you get the patient to look<br />

down, you might notice an inferior serous retinal<br />

detachment. However, even a small bit of fluid is<br />

important to spot and so if you’ve got a camera,<br />

try putting it on autofluorescence; if it’s leaking<br />

fluid, this will show up white beside the tumour.<br />

OCT of course also comes in handy here, as it will<br />

show fluid directly.<br />

S is for symptoms<br />

If your patient has an itchy eye, that’s a symptom<br />

but it really doesn’t have anything to do with<br />

whether there’s a naevus or melanoma in the<br />

fluid. Pain doesn’t matter either (unless it’s huge,<br />

melanoma is not associated with pain, and most<br />

people would suspect that something’s amiss if<br />

you have a really massive melanoma that takes up<br />

the whole eye. The symptoms that really matter<br />

are visual loss (not attributable to some other<br />

cause, of course), field loss or flashes. The flashes<br />

that you get with melanoma are different from the<br />

Moore’s lightening streaks of vitreoretinal traction.<br />

They tend to last longer, maybe a few minutes,<br />

move slowly around, sometimes in circular<br />

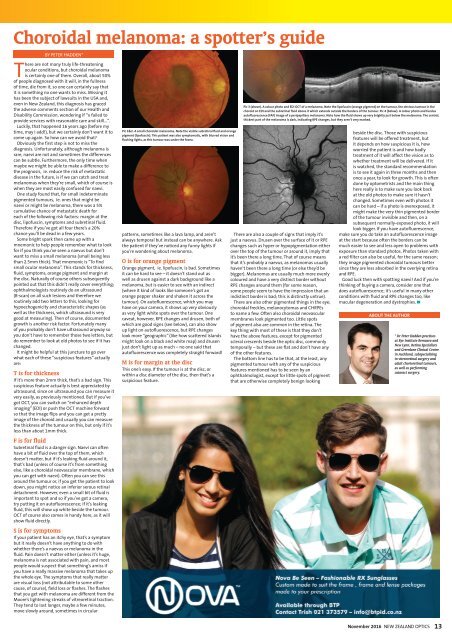

Pic 1&2. A small choroidal melanoma. Note the visible subretinal fluid and orange<br />

pigment (lipofuscin). This patient was also symptomatic, with blurred vision and<br />

flashing lights, as this tumour was under the fovea.<br />

patterns, sometimes like a lava lamp, and aren’t<br />

always temporal but instead can be anywhere. Ask<br />

the patient if they’ve noticed any funny lights if<br />

you’re wondering about melanoma.<br />

O is for orange pigment<br />

Orange pigment, ie. lipofuscin, is bad. Sometimes<br />

it can be hard to see – it doesn’t stand out as<br />

well as drusen against a dark background like a<br />

melanoma, but is easier to see with an indirect<br />

(where it kind of looks like someone’s got an<br />

orange pepper shaker and shaken it across the<br />

tumour). On autofluorescence, which you may<br />

have on your camera, it shows up very obviously<br />

as very light white spots over the tumour. One<br />

caveat, however, RPE changes and drusen, both of<br />

which are good signs (see below), can also show<br />

up light on autofluorescence, but RPE changes<br />

look more “geographic” (like how scattered islands<br />

might look on a black and white map) and drusen<br />

just don’t light up as much – no one said that<br />

autofluorescence was completely straight forward!<br />

M is for margin at the disc<br />

This one’s easy. If the tumour is at the disc, or<br />

within a disc diameter of the disc, then that’s a<br />

suspicious feature.<br />

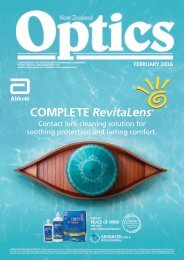

Pic 3 (above). A colour photo and EDI OCT of a melanoma. Note the lipofuscin (orange pigment) on the tumour, the obvious tumour in the<br />

choroid on EDI and the subretinal fluid above it which extends outside the borders of the tumour. Pic 4 (below). A colour photo and fundus<br />

autofluorescence (FAF) image of a peripapillary melanoma. Note how the fluid shows up very brightly just below the melanoma. The central,<br />

thickest part of the melanoma is dark, indicating RPE changes, but they aren’t very marked.<br />

There are also a couple of signs that imply it’s<br />

just a naevus. Drusen over the surface of it or RPE<br />

changes such as hyper or hypopigmentation either<br />

over the top of the tumour or around it, imply that<br />

it’s been there a long time. That of course means<br />

that it’s probably a naevus, as melanomas usually<br />

haven’t been there a long time (or else they’d be<br />

bigger). Melanomas are usually much more evenly<br />

coloured and have a very distinct border without<br />

RPE changes around them (for some reason,<br />

some people seem to have the impression that an<br />

indistinct border is bad; this is distinctly untrue).<br />

There are also other pigmented things in the eye;<br />

choroidal freckles, melanocytomas and CHRPEs<br />

to name a few. Often also choroidal neovascular<br />

membranes look pigmented too. Little spots<br />

of pigment also are common in the retina. The<br />

key thing with most of these is that they don’t<br />

have the above features, except for pigmented<br />

scleral crescents beside the optic disc, commonly<br />

temporally – but these are flat and don’t have any<br />

of the other features.<br />

The bottom line has to be that, at the least, any<br />

pigmented tumour with any of the suspicious<br />

features mentioned has to be seen by an<br />

ophthalmologist, except for little spots of pigment<br />

that are otherwise completely benign looking<br />

beside the disc. Those with suspicious<br />

features will be offered treatment, but<br />

it depends on how suspicious it is, how<br />

worried the patient is and how badly<br />

treatment of it will affect the vision as to<br />

whether treatment will be delivered. If it<br />

is watched, the standard recommendation<br />

is to see it again in three months and then<br />

once a year, to look for growth. This is often<br />

done by optometrists and the main thing<br />

here really is to make sure you look back<br />

at the old photos to make sure it hasn’t<br />

changed. Sometimes even with photos it<br />

can be hard – if a photo is overexposed, it<br />

might make the very thin pigmented border<br />

of the tumour invisible and then, on a<br />

subsequent normally-exposed photo, it will<br />

look bigger. If you have autofluorescence,<br />

make sure you do take an autofluorescence image<br />

at the start because often the borders can be<br />

much easier to see and less open to problems with<br />

exposure than standard photos. Photos taken with<br />

a red filter can also be useful, for the same reason;<br />

they image pigmented choroidal tumours better<br />

since they are less absorbed in the overlying retina<br />

and RPE.<br />

Good luck then with spotting naevi! And if you’re<br />

thinking of buying a camera, consider one that<br />

does autofluorescence; it’s useful in many other<br />

conditions with fluid and RPE changes too, like<br />

macular degeneration and dystrophies. ▀<br />

ABOUT THE AUTHOR<br />

* Dr Peter Hadden practises<br />

at Eye Institute Remuera and<br />

New Lynn, Retina Specialists<br />

and Greenlane Clinical Centre<br />

in Auckland, subspecialising<br />

in vitreoretinal surgery and<br />

adult chorioretinal tumours,<br />

as well as performing<br />

cataract surgery.<br />

<strong>Nov</strong>ember <strong>2016</strong><br />

NEW ZEALAND OPTICS<br />

13