JOVIS Catalog 2019

https://www.jovis.de/en/landing.html

https://www.jovis.de/en/landing.html

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

48<br />

#saopaulo #monuments<br />

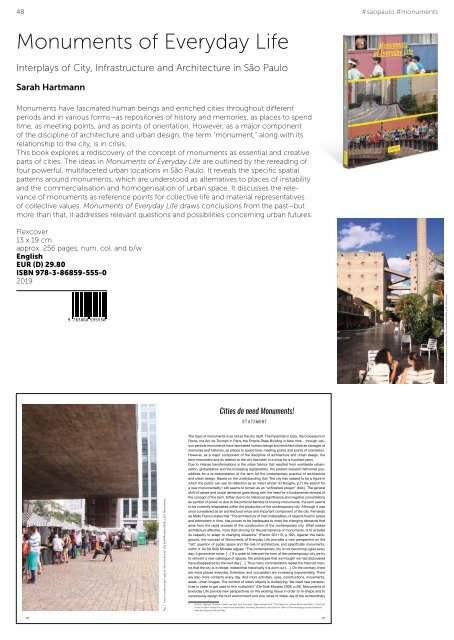

Monuments of Everyday Life<br />

Interplays of City, Infrastructure and Architecture in São Paulo<br />

Sarah Hartmann<br />

Monuments have fascinated human beings and enriched cities throughout different<br />

periods and in various forms—as repositories of history and memories, as places to spend<br />

time, as meeting points, and as points of orientation. However, as a major component<br />

of the discipline of architecture and urban design, the term “monument,” along with its<br />

relationship to the city, is in crisis.<br />

This book explores a rediscovery of the concept of monuments as essential and creative<br />

parts of cities. The ideas in Monuments of Everyday Life are outlined by the rereading of<br />

four powerful, multifaceted urban locations in São Paulo. It reveals the specific spatial<br />

patterns around monuments, which are understood as alternatives to places of instability<br />

and the commercialisation and homogenisation of urban space. It discusses the relevance<br />

of monuments as reference points for collective life and material representatives<br />

of collective values. Monuments of Everyday Life draws conclusions from the past—but<br />

more than that, it addresses relevant questions and possibilities concerning urban futures.<br />

Flexcover<br />

13 x 19 cm<br />

approx. 256 pages, num. col. and b/w<br />

English<br />

EUR (D) 29.80<br />

ISBN 978-3-86859-555-0<br />

<strong>2019</strong><br />

9 783868 595550<br />

Fig. 6. tives in order to get used to this multiplicity” (De Solà-Morales 2008, p.26). Monuments<br />

50<br />

Cities do need Monuments!<br />

STATEMENT<br />

Fig. 1. tives in order to get used to this multiplicity” (De Solà-Morales 2008, p.26). Monuments<br />

The topic of monuments is as old as the city itself. The Pyramids in Giza, the Colosseum in<br />

Rome, the Arc de Triumph in Paris, the Empire State Building in New York... through various<br />

periods monuments have fascinated human beings and enriched cities as storages of<br />

memories and histories, as places to spend time, meeting points and points of orientation.<br />

However, as a major component of the discipline of architecture and urban design, the<br />

term monument and its relation to the city has been in a crisis for a hundred years.<br />

Due to intense transformations in the urban fabrics that resulted from worldwide urbanisation,<br />

globalisation and the increasing digitalisation, the present research fathomed possibilities<br />

for a re-interpretation of the term for the contemporary practice of architecture<br />

and urban design. Based on the understanding that “the city has ceased to be a figure in<br />

which the public can see its reflection as an intact whole” (D’Hooghe, p.7) the search for<br />

a new monumentality1 still seems to remain as an “unfinished project” (ibid.). The general<br />

shift of values and social demands goes along with the need for a fundamental renewal of<br />

the concept of the term. Either due to its historical significance and negative connotations<br />

as symbol of power or due to the pictorial flatness of touristy monuments, the term seems<br />

to be currently dilapidated within the production of the contemporary city. Although it was<br />

once considered as an architectural virtue and important component of the city. Fernando<br />

de Mello Franco states that “The architecture of inert materialities, of objects fixed in space<br />

and permanent in time, has proven to be inadequate to meet the changing demands that<br />

arise from the rapid process of the construction of the contemporary city. What makes<br />

architecture effective, more than striving for the permanence of monuments, is to activate<br />

its capacity to adapt to changing situations” (Franco 2011 B, p.182). Against this background,<br />

the concept of Monuments of Everyday Life provides a new perspective on the<br />

“old” question of public space and the role of architecture, and specifically monuments,<br />

within it. As De Solà Morales argues: “The contemporary city is not becoming uglier every<br />

day: it grows ever richer. […] If in order to interpret the form of the contemporary city we try<br />

to reinvent a new catalogue of spaces, the prototypes that we thought we had discovered<br />

have disappeared by the next day […]. Thus many commentators repeat the tired old mantra<br />

that the city is in retreat, indeed that historically it is worn out […]. On the contrary, there<br />

are more places everyday. Extension and occupation are increasing exponentially. There<br />

are also more contacts every day. And more activities, uses, constructions, movements,<br />

areas, urban images. The number of urban objects is multiplying. We need new perspectives<br />

in order to get used to this multiplicity” (De Solà-Morales 2008, p.26). Monuments of<br />

Everyday Life provide new perspectives on the existing tissue in order to re-shape and to<br />

consciously design the built environment and vice versa to make use of the extraordinary<br />

1 At first, Sigfried Giedion, José Luis Sert and Fernand Láger strived with “The Need for a New Monumentality” (1944) as<br />

a the modern voices for a new monumentality, involving architects and artist in view of the emerging social problems<br />

after the Second World War.<br />

18 19