July 2018 - Sneak Peek

The American Philatelist is the monthly journal of the American Philatelic Society, the world's largest organization for stamp collectors and enthusiasts. Members receive the printed magazine and can access the digital edition as a benefit of membership in the Society. Please enjoy this sneak peek. We're confident that once you see all that we offer, you'll want to join the APS today.

The American Philatelist is the monthly journal of the American Philatelic Society, the world's largest organization for stamp collectors and enthusiasts. Members receive the printed magazine and can access the digital edition as a benefit of membership in the Society. Please enjoy this sneak peek. We're confident that once you see all that we offer, you'll want to join the APS today.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Intelligence and counterintelligence have always played<br />

crucial roles during wartime. Vigilance against the surreptitious<br />

passing of messages to the enemy can make the difference<br />

between victory and defeat, and it has long been documented<br />

that the mails were an important means of sending<br />

clandestine information. Seemingly innocuous letters and<br />

postal cards have been known to have been written in code,<br />

contain microprinting on the back of postage stamps or secret<br />

writing in invisible ink.<br />

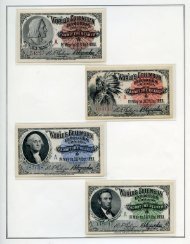

The postal card shown [at left and below] is a good example<br />

of means used to thwart the clandestine passing of<br />

information. The card was mailed from Kalmar, Sweden, to<br />

“Rotary International” in Zurich, Switzerland. The card was<br />

posted on February 8, 1945, only months prior to the end<br />

of World War II. Despite its status as a neutral country, or<br />

perhaps because of it, Sweden was a backdrop for international<br />

espionage. Because of the flow of diplomats, businessmen,<br />

and refugees, Stockholm has been referred to by some<br />

sources as the “Casablanca of the North.”<br />

Switzerland was another one of only eight neutral European<br />

countries in World War II. The others were Portugal,<br />

Spain, Ireland and the postage stamp-sized countries of Vatican,<br />

Liechtenstein and Andorra. So, it’s not surprising that<br />

mail between Sweden and Switzerland would be especially<br />

scrutinized by the Germans. Like most items mailed throughout<br />

Europe during the war, the card shown was subjected to<br />

German military censorship, as indicated by the Nazi censorship<br />

marking in red, along with the red “714,” presumably<br />

another censorship marking. It contains a rather mundane<br />

message, written in German, which translates as follows:<br />

January 27, I sent you my account for January, which had as a<br />

total sum 354.40 Swedish Crowns, and I also asked you to send<br />

me a sum of 450 Swedish Crowns for the costs of the Radiorede<br />

(translation unknown), requested by the directors on February<br />

23. Please telegraph me if you have received these letters and<br />

answered.<br />

With warmest regards,<br />

C.H. Trolle<br />

Please send me a copy of the last Rotary directory of Europe.<br />

The particularly interesting aspect of this card is that in<br />

addition to the censor markings, it also was tested for secret<br />

handwriting by brushing a chemical such as copper sulfate<br />

across the front and back of the card. I am among those<br />

who think this can occasionally be seen as a blue streak on<br />

German-censored covers, particularly those sent by foreign<br />

workers in Germany or on postal items sent to or from international<br />

organizations. This card, which was not addressed<br />

to any individual by name, would seem to have been a prime<br />

candidate for espionage activity.<br />

A C. Harald Trolle, of Kalmar, Sweden, is listed in the<br />

September 1945 issue of The Rotarian. He was named as the<br />

newly appointed committee member responsible for the admission<br />

of clubs for Continental Europe, North Africa and<br />

the Eastern Mediterranean region. While the message may<br />

be totally innocent, it contains enough numbers and dates to<br />

be a coded missive.<br />

Another prime candidate that could conceivably be rife<br />

with subterfuge is a postal card shown from Portugal [Figure<br />

1]. The card was posted in Lisbon, Portugal (Lisboa Central)<br />

on June 4, 1943, and also was sent to Zurich. Once again,<br />

two neutral countries were involved, one of which, Portugal,<br />

is considered by most historians to have been the capital of<br />

espionage during World War II.<br />

The card was sent to a Mademoiselle E.P. Achard at 21<br />

Boersenstrasse, Zurich, with a return address in Lisbon. It is<br />

written in French and translates as follows:<br />

Lisbon<br />

June 4, 1943<br />

Dear Mademoiselle,<br />

I have just now received your letter of May 29, for which I<br />

thank you. As for the question of reimbursements, let’s no longer<br />

talk about it: I am very happy to be of some use to two sons<br />

of my colleagues.<br />

Please accept, dear mademoiselle, my best regards.<br />

E. Bastof<br />

Kalmar, Sweden<br />

8 February 1945<br />

On December 29 I sent you my bill for December (in original)<br />

and on Dec. 30, a copy, but as of today, I have not heard<br />

from you. Today, I received from you the Bulletin No. 2 of 25<br />

January. Please check if you have received my invoice. It was<br />

for 248.50 Swedish Crowns, part of which was for the director<br />

and part of which was as a member of the committee. On<br />

The woman apparently asked the writer for some sort of<br />

favor to help the sons of a mutual acquaintance, to which the<br />

writer agreed. As with the first postal card, this is apparently<br />

a very innocent and innocuous correspondence. However,<br />

there is a lightly stamped circular German “Oberkommando<br />

der Wermacht” (OKW) postmark in red on the address<br />

side – along the red graphic at top. On this postal card, the<br />

secret writing detector brush strokes occur only on the mes-<br />

JULY <strong>2018</strong> / AMERICAN PHILATELIST 647