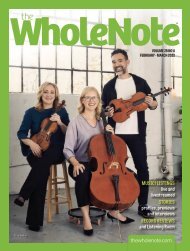

Volume 24 Issue 6 - March 2019

Something Old, Something New! The Ide(a)s of March are Upon Us! Rob Harris's Rear View Mirror looks forward to a tonal revival; Tafelmusik expands their chronological envelope in two directions, Esprit makes wave after wave; Pax Christi's new oratorio by Barbara Croall catches the attention of our choral and new music columnists; and summer music education is our special focus, right when warm days are once again possible to imagine. All this and more in our March 2019 edition, available in flipthrough here, and on the stands starting Thursday Feb 28.

Something Old, Something New! The Ide(a)s of March are Upon Us! Rob Harris's Rear View Mirror looks forward to a tonal revival; Tafelmusik expands their chronological envelope in two directions, Esprit makes wave after wave; Pax Christi's new oratorio by Barbara Croall catches the attention of our choral and new music columnists; and summer music education is our special focus, right when warm days are once again possible to imagine. All this and more in our March 2019 edition, available in flipthrough here, and on the stands starting Thursday Feb 28.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

World War II, so the order is essentially inconsequential.”<br />

Beecroft began organizing her enterprise in 1977, in a series of<br />

letters to her intended subjects in Europe. She told me she was confident<br />

in positive responses from the composers since she was known<br />

to them, and that they trusted her knowledge of the subject. She was<br />

by this time acknowledged not only as a composer, but as a highly<br />

skilled broadcaster, and she had easy access to all her subjects. She<br />

told me that Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001), for example, said: “One<br />

thing I like about you is your determination.” Her travels took her<br />

first to Cologne, Berlin, Köthen, then Paris, London, and Utrecht.<br />

Additional interviews were scheduled in the United States, and back<br />

home in her Toronto studio, when possible.<br />

The results of all these interviews were highly rewarding, and<br />

revealed great amounts of both historical and personal details.<br />

Beecroft’s subjects opened up to her highly focused line of questioning,<br />

delving into the recent past, to a time when they were all drawn to the<br />

artistic and technical challenges of this new musical medium. In the<br />

very first interview, for example,<br />

with Pierre Schaeffer (1910–<br />

1995), inventor of the concept of<br />

musique concrète using recorded<br />

sounds, and who founded Le Club<br />

d’Essai in 1942 and the Groupe<br />

de Recherche Musicales in 1958<br />

in Paris, it’s immediately clear<br />

that Schaeffer’s focus is primarily<br />

on research and engineering.<br />

He refers to clashes in methodology<br />

with Pierre Boulez (1925–<br />

2016), Karlheinz Stockhausen<br />

(1928–2007) and Iannis Xenakis,<br />

and confesses: “I hate dodecaphonic<br />

music, and I often say<br />

that the Austrians shot music<br />

with 12 bullets, they killed it for a<br />

Bruce Mather<br />

long time.” This was a somewhat<br />

surprising revelation for me, but is typical of the sort of candid views<br />

Beecroft’s colleagues were willing to share with her.<br />

In the Stockhausen interview, by contrast, we find the other side of<br />

the argument. “In Paris I became involved in the musique concrète<br />

that was at that time just beginning to develop. Boulez made me listen<br />

to a very few, very short studies, and immediately I was interested<br />

in trying myself to synthesize sound, and to get away from the treatment<br />

of recorded sound.” Stockhausen went on to mention his collaboration<br />

with Belgian composer Karel Goeyvaerts, who had suggested<br />

a technique of combining pure sine waves to synthesize timbres: “I<br />

have to say that the friendship with this Belgian composer, and the<br />

exchange of letters with him, was a very important reason why I made<br />

these first experiments, because we were both thinking that it would<br />

be a marvellous thing if we could synthesize timbres. The general idea<br />

of timbre composition was in the air from texts of Schoenberg.”<br />

Goeyvaerts recalled in his interview: “I never thought that pure sine<br />

waves could be heard. And suddenly I found that they existed with an<br />

electronic generator, so I wrote to Stockhausen and said, now we can<br />

go ahead.” He added: “When Stockhausen made the Study No. 1 and<br />

when I made my piece in 1953, I must say we considered at last we<br />

could come to a pure structure.” It was also in this year that the term<br />

“electronic music” was coined by Dr. Herbert Eimert (1897–1972) at<br />

the studio of the Cologne Radio.<br />

Historical turning points such as these appear often throughout<br />

Beecroft’s Conversations with Post World War II Pioneers of Electronic<br />

Music. But as important as such details are, the personal notes of the<br />

composers are possibly the more interesting aspect. An example is in<br />

the interview with American composer Otto Luening (1900–1996),<br />

who studied with composer and virtuoso pianist, Ferruccio Busoni<br />

(1866–19<strong>24</strong>), and was friends with composer Edgard Varèse (1883–<br />

1965). Luening said, of Busoni: “The essence of music, the inner core of<br />

music was to him still a mystery and he was like Schopenhauer in that,<br />

who I believe said somewhere if we knew the mystery and relationships<br />

of music, we would know the mystery and relationships of the whole<br />

“The publication is not intended to be a<br />

scholarly document on technical matters<br />

but an insight into the internal world of<br />

the composer and sociological forces that<br />

helped shape the person.”<br />

— Norma Beecroft to Karlheinz Stockhausen<br />

universe.” And of Varèse, Luening said: “We immediately hit it off.<br />

Not only did I have great affection for him, and liked him very much<br />

personally, but we had this Busoni tie.” He mentioned the various<br />

stylistic groups of American composers current and pointed out:<br />

“Varèse and I were on this other line, we were really free wheelers,<br />

you know, and while we had a very strong aesthetic, it was not<br />

organized, there was no movement or anything, and we never<br />

wanted one. We used to talk together and so gradually we fell<br />

into a group of friends, that were very interesting and all kind of<br />

iconoclasts.”<br />

These personal snapshots were entirely a part of Beecroft’s focus<br />

and plan for her project. In a letter to Stockhausen after the first<br />

edits were finished, she told him: “The publication is not intended<br />

to be a scholarly document on technical matters but an insight<br />

into the internal world of the composer and sociological forces<br />

that helped shape the person.” She projected to him that, “I am<br />

sure this modest document<br />

will help fill a void when it<br />

comes to musical matters in<br />

the latter half of this century.”<br />

The book is available through<br />

the Canadian Music Centre,<br />

20 St. Joseph Street, Toronto,<br />

and can also be ordered online.<br />

The details can be found here:<br />

musiccentre.ca/node/155113.<br />

Norma Beecroft continues to<br />

compose. Montreal composerpianist<br />

Bruce Mather invited<br />

her to create a work for his<br />

Harry Somers<br />

Carrillo piano, an instrument<br />

with 96 notes to the<br />

octave, which is to say, it’s<br />

tuned in 16ths of tones. Beecroft’s new composition will have its<br />

world premiere on <strong>March</strong> 11 at 7:30 at the Salle de concert of the<br />

Conservatoire de musique de Montreal, 4750 avenue Henri-Julien.<br />

It’s a work for solo Carrillo piano with digital soundtracks. Beecroft<br />

wrote: “Written for my friend and colleague Bruce Mather, this piece<br />

posed challenges that I could not resist. Having worked in analogue<br />

studios for most of my career, I determined to try my hand at<br />

composing using digital software only. The Carrillo piano was another<br />

challenge, as the entire piano keyboard consists of only one octave of<br />

sound. Training my ears to hear the microtones was a new problem,<br />

as was a system of notation for the performer. Herewith – my modest<br />

attempt at combining the two elements!” She explains further that<br />

the work’s design, “finds its analogy in nature, with the opening and<br />

closing of a flower. The one octave is divided in half and opens up<br />

slowly to create ever-widening intervals. And the flower slowly ends<br />

its fragile existence in a retrograde movement.”<br />

Also in Montreal in <strong>March</strong>, a special dramatic concert presentation<br />

titled “Between Composers: Correspondence of Norma Beecroft and<br />

Harry Somers, 1955–1960” will take place at the Tanna Schulich Hall<br />

of McGill University on <strong>March</strong> 22 at 7:30pm. Composer and McGill<br />

music professor Brian Cherney conceived the presentation, and he<br />

describes the idea:<br />

continues to page 92<br />

14 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2019</strong> thewholenote.com