Volume 24 Issue 6 - March 2019

Something Old, Something New! The Ide(a)s of March are Upon Us! Rob Harris's Rear View Mirror looks forward to a tonal revival; Tafelmusik expands their chronological envelope in two directions, Esprit makes wave after wave; Pax Christi's new oratorio by Barbara Croall catches the attention of our choral and new music columnists; and summer music education is our special focus, right when warm days are once again possible to imagine. All this and more in our March 2019 edition, available in flipthrough here, and on the stands starting Thursday Feb 28.

Something Old, Something New! The Ide(a)s of March are Upon Us! Rob Harris's Rear View Mirror looks forward to a tonal revival; Tafelmusik expands their chronological envelope in two directions, Esprit makes wave after wave; Pax Christi's new oratorio by Barbara Croall catches the attention of our choral and new music columnists; and summer music education is our special focus, right when warm days are once again possible to imagine. All this and more in our March 2019 edition, available in flipthrough here, and on the stands starting Thursday Feb 28.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Beat by Beat | On Opera<br />

Claude Vivier’s<br />

Kopernikus<br />

A Hopeful<br />

Homecoming<br />

SOPHIE BISSON<br />

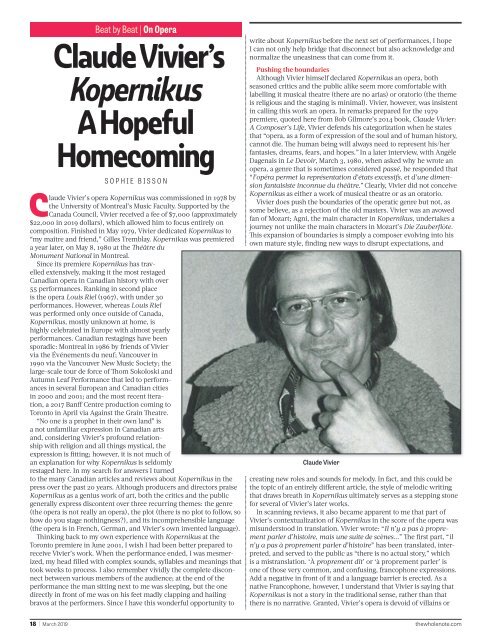

Claude Vivier’s opera Kopernikus was commissioned in 1978 by<br />

the University of Montreal’s Music Faculty. Supported by the<br />

Canada Council, Vivier received a fee of $7,000 (approximately<br />

$22,000 in <strong>2019</strong> dollars), which allowed him to focus entirely on<br />

composition. Finished in May 1979, Vivier dedicated Kopernikus to<br />

“my maître and friend,” Gilles Tremblay. Kopernikus was premiered<br />

a year later, on May 8, 1980 at the Théâtre du<br />

Monument National in Montreal.<br />

Since its premiere Kopernikus has travelled<br />

extensively, making it the most restaged<br />

Canadian opera in Canadian history with over<br />

55 performances. Ranking in second place<br />

is the opera Louis Riel (1967), with under 30<br />

performances. However, whereas Louis Riel<br />

was performed only once outside of Canada,<br />

Kopernikus, mostly unknown at home, is<br />

highly celebrated in Europe with almost yearly<br />

performances. Canadian restagings have been<br />

sporadic: Montreal in 1986 by friends of Vivier<br />

via the Événements du neuf; Vancouver in<br />

1990 via the Vancouver New Music Society; the<br />

large-scale tour de force of Thom Sokoloski and<br />

Autumn Leaf Performance that led to performances<br />

in several European and Canadian cities<br />

in 2000 and 2001; and the most recent iteration,<br />

a 2017 Banff Centre production coming to<br />

Toronto in April via Against the Grain Theatre.<br />

“No one is a prophet in their own land” is<br />

a not unfamiliar expression in Canadian arts<br />

and, considering Vivier’s profound relationship<br />

with religion and all things mystical, the<br />

expression is fitting; however, it is not much of<br />

an explanation for why Kopernikus is seldomly<br />

restaged here. In my search for answers I turned<br />

to the many Canadian articles and reviews about Kopernikus in the<br />

press over the past 20 years. Although producers and directors praise<br />

Kopernikus as a genius work of art, both the critics and the public<br />

generally express discontent over three recurring themes: the genre<br />

(the opera is not really an opera), the plot (there is no plot to follow, so<br />

how do you stage nothingness?), and its incomprehensible language<br />

(the opera is in French, German, and Vivier’s own invented language).<br />

Thinking back to my own experience with Kopernikus at the<br />

Toronto premiere in June 2001, I wish I had been better prepared to<br />

receive Vivier’s work. When the performance ended, I was mesmerized,<br />

my head filled with complex sounds, syllables and meanings that<br />

took weeks to process. I also remember vividly the complete disconnect<br />

between various members of the audience; at the end of the<br />

performance the man sitting next to me was sleeping, but the one<br />

directly in front of me was on his feet madly clapping and hailing<br />

bravos at the performers. Since I have this wonderful opportunity to<br />

write about Kopernikus before the next set of performances, I hope<br />

I can not only help bridge that disconnect but also acknowledge and<br />

normalize the uneasiness that can come from it.<br />

Pushing the boundaries<br />

Although Vivier himself declared Kopernikus an opera, both<br />

seasoned critics and the public alike seem more comfortable with<br />

labelling it musical theatre (there are no arias) or oratorio (the theme<br />

is religious and the staging is minimal). Vivier, however, was insistent<br />

in calling this work an opera. In remarks prepared for the 1979<br />

premiere, quoted here from Bob Gilmore’s 2014 book, Claude Vivier:<br />

A Composer’s Life, Vivier defends his categorization when he states<br />

that “opera, as a form of expression of the soul and of human history,<br />

cannot die. The human being will always need to represent his/her<br />

fantasies, dreams, fears, and hopes.” In a later interview, with Angèle<br />

Dagenais in Le Devoir, <strong>March</strong> 3, 1980, when asked why he wrote an<br />

opera, a genre that is sometimes considered passé, he responded that<br />

“l’opéra permet la représentation d’états excessifs, et d’une dimension<br />

fantaisiste inconnue du théâtre.” Clearly, Vivier did not conceive<br />

Kopernikus as either a work of musical theatre or as an oratorio.<br />

Vivier does push the boundaries of the operatic genre but not, as<br />

some believe, as a rejection of the old masters. Vivier was an avowed<br />

fan of Mozart; Agni, the main character in Kopernikus, undertakes a<br />

journey not unlike the main characters in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte.<br />

This expansion of boundaries is simply a composer evolving into his<br />

own mature style, finding new ways to disrupt expectations, and<br />

Claude Vivier<br />

creating new roles and sounds for melody. In fact, and this could be<br />

the topic of an entirely different article, the style of melodic writing<br />

that draws breath in Kopernikus ultimately serves as a stepping stone<br />

for several of Vivier’s later works.<br />

In scanning reviews, it also became apparent to me that part of<br />

Vivier’s contextualization of Kopernikus in the score of the opera was<br />

misunderstood in translation. Vivier wrote: “Il n’y a pas à proprement<br />

parler d’histoire, mais une suite de scènes...” The first part, “il<br />

n’y a pas à proprement parler d’histoire” has been translated, interpreted,<br />

and served to the public as “there is no actual story,” which<br />

is a mistranslation. ‘À proprement dit’ or ‘à proprement parler’ is<br />

one of those very common, and confusing, francophone expressions.<br />

Add a negative in front of it and a language barrier is erected. As a<br />

native Francophone, however, I understand that Vivier is saying that<br />

Kopernikus is not a story in the traditional sense, rather than that<br />

there is no narrative. Granted, Vivier’s opera is devoid of villains or<br />

18 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2019</strong> thewholenote.com