ZEKE Fall 2019

Contents includes: "Youth of Belfast" by Toby Binder, and "Delta Hill Riders" by Rory Doyle, winners of ZEKE Award for Documentary Photography "Rising Tides" with photographs by Sean Gallagher, Lauren Owens Lambert, and Michael O. Snyder "Out of the Shadows: Shamed Teen Mothers of Rwanda" by Carol Allen Storey Interview with Lekgetho Makola, Head of Market Photo Workshop, South Africa, by Caterina Clerici "Why Good Pictures of Bad Things Matter" by Glenn Ruga Book Reviews and more...

Contents includes:

"Youth of Belfast" by Toby Binder, and "Delta Hill Riders" by Rory Doyle, winners of ZEKE Award for Documentary Photography

"Rising Tides" with photographs by Sean Gallagher, Lauren Owens Lambert, and Michael O. Snyder

"Out of the Shadows: Shamed Teen Mothers of Rwanda" by Carol Allen Storey

Interview with Lekgetho Makola, Head of Market Photo Workshop, South Africa, by Caterina Clerici

"Why Good Pictures of Bad Things Matter" by Glenn Ruga

Book Reviews and more...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2018 <strong>2019</strong> VOL.4/NO.2 VOL.5/NO.2 $9.95 US/$10.95 US/$11 CANADA<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong>FALL<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network

FALL <strong>2019</strong> VOL.5/NO.2<br />

$10 US/$11 CANADA<br />

Toby Binder from Youth of Belfast<br />

Rory Doyle from Delta Hill Riders<br />

Michael O. Snyder from Rising Tides<br />

Carol Allen-Storey from Out of the Shadows<br />

2 | YOUTH OF BELFAST<br />

Photographs by Toby Binder<br />

WINNER OF <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Text by Alessandra Bergamin<br />

14 | DELTA HILL RIDERS<br />

Photographs by Rory Doyle<br />

WINNER OF <strong>ZEKE</strong> AWARD FOR DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

Text by Zeb Larson<br />

26 | RISING TIDES<br />

Photographs by Sean Gallagher, Lauren Owens Lambert,<br />

Michael O. Snyder<br />

Text by Tammy Danan<br />

44<br />

|<br />

OUT OF THE SHADOWS:<br />

SHAMED TEEN MOTHERS IN RWANDA<br />

Photographs by Carol Allen-Storey<br />

40 | Aesthetics of Documentary:<br />

Why Good Pictures of Bad Things Matter<br />

by Glenn Ruga<br />

43 | Contributors<br />

52 | Interview with Lekgetho Makola<br />

by Caterina Clerici<br />

54 | Book Reviews<br />

60 | Award Winners<br />

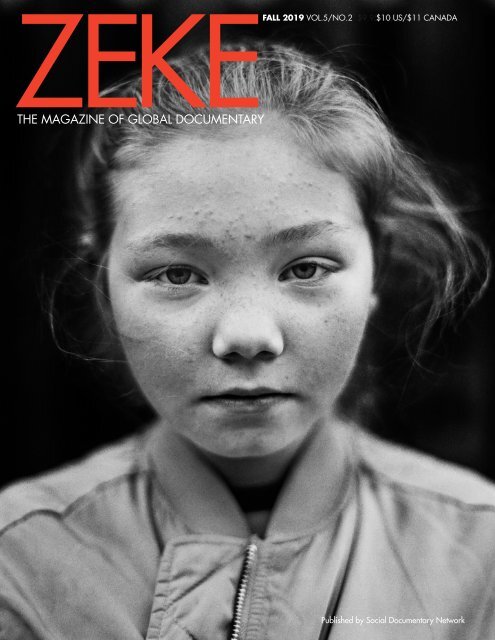

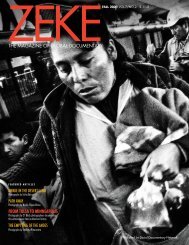

On the Cover<br />

Emily. Photo by Toby Binder from<br />

Youth of Belfast<br />

Lekgetho Makola from Market Photo Workshops,<br />

South Africa. Photo by Siphosihle Mkhwanazi

<strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

THE<br />

MAGAZINE OF<br />

GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

Published by Social Documentary Network<br />

Dear <strong>ZEKE</strong> Readers:<br />

Welcome to the tenth issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine!<br />

What keeps us going is 1) our love of the photographic image, and 2) our belief in the<br />

ability of photographs to communicate important information about our world, especially<br />

at a time when our experiences are more visual than ever. To lay out a greater case for<br />

the documentary image, I hope you will take a few minutes to read the essay I wrote on<br />

page 40 of this issue about the aesthetics of documentary photography and why good<br />

photos of bad things matter. I believe, more than anything, this describes why documentary<br />

photography matters to me.<br />

In this issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, we are proud to feature the work of the winners of the first <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

Award for Documentary Photography, Toby Binder (Germany) and Rory Doyle (US), in<br />

addition to features on Rising Tides with photographers Lauren Owens Lambert and<br />

Michael O. Snyder (both from the US), and Sean Gallagher (based in Hong Kong);<br />

and finally a feature on teen pregnancy in Rwanda by UK-based photographer<br />

Carol Allen-Storey.<br />

As a prelude to the next issue of <strong>ZEKE</strong>, we have an interview by Caterina Clerici with<br />

Lekgetho Makola, Head of the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, South Africa. What<br />

we learned from this interview is there is a remarkable photo community in Africa, which we<br />

know little about here. We look forward to exploring this vibrant community in the next issue<br />

of <strong>ZEKE</strong> which will be a special issue on photography in Africa, guest-edited by Makola.<br />

At the time I am writing this letter, the US is reeling from two mass shootings—in El Paso,<br />

Texas and Dayton, Ohio. The first by an avowed white supremacist espousing racial hatred<br />

and the second by a mentally ill person just filled with hate. What these two shooters have<br />

in common is that they are white, male, and have unfettered access to semi-automatic high<br />

powered weapons. While I wouldn’t suggest putting any restrictions on the first two qualities<br />

(some may disagree with this position), it is long overdue that we question whether highly<br />

dangerous and lethal weapons should be freely available to anyone. We don’t allow access<br />

to automatic weapons or certain classes of explosives; we enforce speed limits; we heavily<br />

regulate food, children’s toys, medicines, automobiles and many other aspects of our society.<br />

It is about time we outlaw these weapons.<br />

But the connection I see between photography and mass shootings in the US is not the<br />

obvious one—it is not to shine light on the shooters or the massacres. Rather it is to shine<br />

light on the sanctity of the lives of everyone else—me, you, our families, friends, coworkers,<br />

fellow citizens in these united states of America, and to make a case why these lives<br />

need to take precedent over the dubious right to own weapons of mass destruction. What<br />

photography does so well is to describe individual people and to help us see both our<br />

common humanity and our common diversity, all deserving of equal love and protection.<br />

Matthew Lomanno<br />

Glenn Ruga<br />

Executive Editor<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 1

YOUTH OF<br />

BELFAST<br />

Photographs by Toby Binder<br />

Northern Ireland will have to<br />

leave the European Union due<br />

to UK’s Brexit referendum in<br />

2016, although a majority of its<br />

citizens voted to remain. While<br />

the local Protestant Unionists<br />

voted to leave, the Catholic Nationalists<br />

wanted to remain within the EU.<br />

This photo essay covers the situation<br />

of young people in Catholic and<br />

Protestant neighborhoods of Belfast.<br />

It shows that kids in Northern Ireland<br />

often suffer the same problems no matter<br />

if they live on one or the other side of<br />

the wall: unemployment, drug abuse,<br />

violence and lack of perspectives are<br />

often omnipresent.<br />

Toby Binder, born in 1977 in<br />

Germany, studied at the Stuttgart State<br />

Academy of Art and Design. He focused<br />

his photography on social, environmental<br />

and political topics. Now based<br />

in Argentina and Germany, he works<br />

on assignments and personal projects<br />

where he finds his topics in post-war<br />

and crisis situations as well as in the<br />

daily life of people.<br />

His work is patient and intimate,<br />

without being pervasive and has been<br />

awarded internationally: the Nannen-<br />

Preis in 2017, the Sony World Photo<br />

Awards in 2017 and <strong>2019</strong>, and the<br />

Philip Jones Griffiths Award in 2018.<br />

In that year, he received an Honorable<br />

Mention at the UNICEF Photo of the<br />

Year.<br />

His work is published by Stern,<br />

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, die<br />

Zeit, Greenpeace Magazin, Amnesty<br />

Journal, Neue Zürcher Zeitung and<br />

others.<br />

2 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Megan (16) and Joshua (17)<br />

photographed in 2017 at N<br />

Howard link, Shankill. They are<br />

still together and have a baby<br />

girl. Joshua is working in road<br />

maintenance now.<br />

Not a subscriber? Click here to receive the print version of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL 2015/ <strong>2019</strong>/ 3

Sophie and Jade at a local water<br />

reservoir in Clonard. It’s a popular<br />

spot for teenagers to gather as it’s a<br />

small park with a lake and not seen<br />

from the streets.<br />

4 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL 2015/ <strong>2019</strong>/ 5

Cole, Sandy Row.<br />

6 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Rachel, Clonard.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL 2015/ <strong>2019</strong>/ 7

8 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Young girls sitting on the sidewalk<br />

of Tennent Street, Shankill.<br />

Often there is not much to do<br />

and kids just meet on the streets.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL 2015/ <strong>2019</strong>/ 9

10 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Sean’s Mini Market at Cavendish<br />

Street, Clonard—a typical corner<br />

shop where many teenagers<br />

gather, buy their soft drinks,<br />

cigarettes, crisps and chocolate.<br />

Growing up in Belfast, photographer<br />

Toby Binder said, “these<br />

little shops always were the<br />

places for me to get in touch with<br />

the young people or meet them<br />

again.”<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 11

Youth of Bel<br />

Struggling<br />

with a Legacy<br />

of Conflict and<br />

the Looming<br />

Brexit Crisis<br />

by Alessandra<br />

Bergamin<br />

Photos by Toby Binder<br />

Last April marked more<br />

than twenty years since<br />

the end of Northern<br />

Ireland’s sectarian conflict<br />

known as “the Troubles.” The<br />

more than 30-year war pitted<br />

Irish Catholic nationalists,<br />

who favored unification with<br />

the Republic of Ireland to the<br />

south, against Protestant loyalists<br />

who supported continued<br />

British rule. While memories<br />

of bombings and bloodshed<br />

linger and signs of segregation<br />

still divide the capital city of<br />

Belfast, the country’s youth are<br />

torn between a palpable past<br />

and an uncertain future.<br />

The roots of the Troubles<br />

stretch back to the creation<br />

of Northern Ireland itself. The<br />

Unionist political establishment,<br />

which was largely Protestant,<br />

maintained power over the<br />

Irish Catholic minority through<br />

discriminatory policies. In<br />

the 1960s, inspired by the<br />

American civil rights movement,<br />

the country’s Irish Catholic<br />

community formed a civil<br />

rights association to protest the<br />

systemic discrimination. But the<br />

organization’s peaceful protests<br />

were often met with excessive<br />

force, only heightening tensions<br />

between the police, politicians,<br />

and the movement. As the<br />

situation escalated, the British<br />

Army was deployed to Northern<br />

Ireland, and soon Unionist<br />

and Republican paramilitaries<br />

— such as the Irish Republican<br />

Army (IRA) and the Ulster<br />

Defense Association — formed.<br />

As riots and bombings became<br />

commonplace, brick and steel<br />

“peace walls” were erected to<br />

separate sectarian communities.<br />

The Troubles reached a new,<br />

violent height in 1972 when<br />

British paratroopers opened<br />

fire on Catholic demonstrators<br />

in Derry, killing 13 people and<br />

injuring 14 more. In 2010, an<br />

official inquiry determined that<br />

the attack, which came to be<br />

known as ‘Bloody Sunday,’ was<br />

unjustified.<br />

An actual possibility for<br />

peace wouldn’t arrive until the<br />

late 1990s when the British<br />

and Irish governments and<br />

paramilitary groups met to<br />

discuss a peace treaty. The<br />

talks led to the landmark Good<br />

Friday Agreement in December<br />

12 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

1999 and the creation of the<br />

Northern Ireland Assembly—a<br />

power-sharing legislative<br />

body that has the ability to<br />

make laws in areas including<br />

housing, employment, education,<br />

and health. By the time<br />

the bloodshed and bombings<br />

ceased, more than 3,600<br />

people had died and thousands<br />

more were injured. In the<br />

decades since the treaty was<br />

fast<br />

As the country’s hardwon<br />

power sharing<br />

agreement flounders,<br />

Brexit looms with uncertainty,<br />

and the country’s<br />

youth face issues of<br />

continued segregation<br />

and suicide, a united<br />

Northern Ireland is more<br />

important than ever.<br />

signed peace has been successful,<br />

albeit tenuous. Now, as<br />

the country’s hard-won political<br />

assembly flounders, Brexit<br />

looms with uncertainty, and the<br />

country’s youth face issues of<br />

continued segregation and suicide,<br />

a united Northern Ireland<br />

is more important than ever.<br />

A Legacy of<br />

Violence<br />

While Northern Ireland’s youth<br />

have experienced the fruits of<br />

peace rather than the tribulations<br />

of war, research has<br />

found that intergenerational<br />

trauma continues to affect<br />

the country’s population. A<br />

2010 study by researchers<br />

at the University of Ulster in<br />

Northern Ireland found that<br />

30 years after Bloody Sunday,<br />

the victims’ children and<br />

immediate family members<br />

reported significant psychological<br />

distress. In some cases,<br />

especially among those closest<br />

to the victims, their distress<br />

was comparable to those who<br />

had lived through war itself.<br />

Stephen Mullan, the executive<br />

director of Dreamscheme—an<br />

organization that works with<br />

at-risk youth in Belfast—has<br />

observed this intergenerational<br />

trauma.<br />

“When there’s pain<br />

in your family history,<br />

that’s harder to get over,”<br />

Mullan said. “There’s a lot<br />

of emotion that’s passed<br />

through those stories.”<br />

More broadly, Northern<br />

Ireland’s youth are struggling<br />

with mental health issues,<br />

including anxiety and depression.<br />

The legacy of conflict,<br />

continued discrimination, poverty,<br />

and high unemployment<br />

are all contributing factors.<br />

As a result, Northern Ireland’s<br />

suicide rate is one of the highest<br />

in the United Kingdom.<br />

Between 1999 and 2014,<br />

more than 3,700 people lost<br />

their lives to suicide and nearly<br />

a fifth of those people were<br />

under 25 years old. Studies<br />

have linked the high youth<br />

suicide rate to the conflict in a<br />

number of ways. In particular,<br />

poverty combined with continued<br />

segregation is thought to<br />

increase risk factors that may<br />

result in suicide.<br />

“Kids now are not so much<br />

hurting each other,” Mullan<br />

said. “But hurting themselves.”<br />

Sectarianism &<br />

Segregation<br />

While the country’s ‘peace<br />

walls’ are slowly being torn<br />

down, sectarianism and<br />

segregation still linger. In housing<br />

estates such as Creggan,<br />

where poverty and unemployment<br />

are high, sectarian sentiments<br />

are strong and appear to<br />

be increasing as paramilitaries<br />

regroup. Earlier this year, on<br />

the night before Good Friday,<br />

journalist Lyra McKee was shot<br />

dead during a riot in Creggan.<br />

The New IRA, a radical splinter<br />

group of the original IRA, later<br />

claimed responsibility but no<br />

one has been charged with her<br />

murder.<br />

Segregated schools add<br />

to the problem. Only seven<br />

percent of school-aged children<br />

in Northern Ireland attend an<br />

officially integrated school.<br />

This low percentage has created<br />

a barrier to friendships<br />

that stretch across ideological<br />

lines. These divisions, however,<br />

are disliked by young<br />

people, many of whom prefer<br />

integrated education. Dirk<br />

Schubotz, a senior lecturer at<br />

Queen’s University in Belfast,<br />

directs an annual survey of<br />

16-year-olds across Northern<br />

Ireland and says this growing<br />

preference for integrated<br />

schools reflects young people’s<br />

desire to separate themselves<br />

from the past.<br />

“Young people go out of<br />

their way to say that ‘this is not<br />

our conflict, it’s our parent’s or<br />

our grandparent’s,’” Schubotz<br />

said. “We also live at a time<br />

where religion has become less<br />

important— that’s not unique to<br />

Northern Ireland, but there’s a<br />

different element because of the<br />

conflict.”<br />

Looking Toward<br />

the Future<br />

Even in its uncertainty, the<br />

prospect of Brexit has posed<br />

a new concern for segments<br />

of Northern Ireland’s youth. A<br />

recent report found that 61 percent<br />

of middle-income teenagers<br />

are highly concerned about<br />

withdrawing from the European<br />

Union. Brexit, if enacted, would<br />

have wide-reaching implications<br />

for trade, immigration<br />

and Northern Ireland’s shared<br />

border with the Republic of<br />

Ireland. More locally, Northern<br />

Ireland’s political system has<br />

essentially unraveled. The country’s<br />

power-sharing Assembly<br />

has not been in session for<br />

more than two years due to a<br />

falling out between Republican<br />

and Unionist parties. For many<br />

young people, optimistic that<br />

the future of Northern Ireland<br />

is one of unity, the Assembly’s<br />

failing is a reminder that the<br />

shadow of conflict will be present<br />

as long as divisions persist.<br />

“Most young people<br />

would like Northern Ireland<br />

to progress to the point where<br />

you wouldn’t have to ask if<br />

someone is British or Irish,”<br />

says twenty-one-year old Tara<br />

Grace Connolly who grew up<br />

in Belfast. “We would like a<br />

future of prosperity and progress,<br />

not fear.”<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 13

Delta<br />

Hill<br />

Riders<br />

PHOTOS BY RORY DOYLE<br />

It’s estimated that just after the Civil War,<br />

one in four cowboys was African American.<br />

Yet this population was drastically underrepresented<br />

in popular accounts, and it is<br />

still. The “cowboy” identity retains a strong<br />

presence in many contemporary black<br />

communities.<br />

This ongoing project, “Delta Hill Riders,” sheds<br />

light on the overlooked subculture of African<br />

American cowboys and cowgirls in the rural<br />

Mississippi Delta. The work resists both historical<br />

and contemporary stereotypes. Rory Doyle has<br />

captured black heritage rodeos, horse shows, trail<br />

rides, “Cowboy Night” at black nightclubs, and<br />

subjects’ homes across the Delta.<br />

It’s a story that’s particularly timely with the current<br />

political environment, and one that provides a<br />

renewed focus on rural America. Doyle has captured<br />

a group of riders showing love for their horses<br />

and fellow cowboys/cowgirls, while also passing<br />

down traditions and historical perspectives among<br />

generations.<br />

Rory Doyle is a photographer based in Cleveland,<br />

Mississippi in the rural Mississippi Delta. Born and<br />

raised in Maine, Doyle moved to the South in 2009<br />

and has remained committed to the region ever<br />

since. His work often highlights unique Southern<br />

subcultures commonly overlooked.<br />

Doyle is a 2018 Mississippi Visual Artist Fellow<br />

through the Mississippi Arts Commission and<br />

National Endowment for the Arts for his ongoing<br />

project on African American cowboys and cowgirls,<br />

“Delta Hill Riders.” Doyle won the 16th Annual<br />

Smithsonian Photo Contest with the project in <strong>2019</strong>.<br />

The work was featured in the Half King Photo<br />

Series in New York and The Print Space Gallery in<br />

London before opening at the Delta Arts Alliance<br />

in February <strong>2019</strong>. He was also recognized for the<br />

project by winning the <strong>2019</strong> Zeiss Photography<br />

Award, and the photojournalism category at the<br />

2018 Eye Em Awards in Berlin, Germany.<br />

14 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Bree Wrenn pets her friend’s horse<br />

at sunset in Tallahatchie County,<br />

Mississippi. April <strong>2019</strong>.<br />

Not a subscriber? Click here to receive the print version of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 15

James McGee poses for a<br />

portrait atop his horse in Bolivar<br />

County, Mississippi. November<br />

2017.<br />

16 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 17

Moonie Myles breaks a horse<br />

before a looming storm just<br />

outside Cleveland, Mississippi.<br />

March 2018.<br />

18 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 19

20 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Frank Simpson poses for<br />

a portrait in his home<br />

in Shelby, Mississippi.<br />

November 2017.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 21

Peggy Smith groom her horse,<br />

Big Jake, while others relax in<br />

the afternoon light in Bolivar<br />

County, Mississippi. October<br />

2018.<br />

22 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 23

Black<br />

The American West<br />

has been endlessly mythologized,<br />

and of its many myths, one of<br />

the most enduring is the idea of<br />

the West as a space for white<br />

Euroamericans. Indigenous peoples,<br />

Mexican Americans, and<br />

Asians all existed in the West, but<br />

in popular memory and culture<br />

their presence is either missing<br />

or heavily circumscribed. Like the<br />

West, “cowboy” has taken on<br />

an image all its own: it evokes<br />

a white man on horseback, probably<br />

between 1870 and 1890. Of<br />

those missing groups, however, one<br />

is especially conspicuous: the African<br />

American cowboy. In a February<br />

2017 issue of Smithsonian Magazine,<br />

journalist Katie Nomjimbadem<br />

estimated that as many as one in four<br />

cowboys was black.<br />

Enslaved Cowboys<br />

Before the United States had declared<br />

its independence from Great Britain,<br />

enslaved persons were working as<br />

cowhands and ranchers in parts of<br />

the Carolinas. Even before emancipation<br />

and the end of the Civil<br />

War, enslaved persons worked as<br />

cowboys in parts of the American<br />

South. Once Texas was added to<br />

the union, enslaved persons working<br />

as cowboys became normal there.<br />

Historian Peter Wood notes that some<br />

plantation owners went so far as to<br />

request new slaves from the Gambia<br />

River region in Africa because they<br />

were accustomed to working with<br />

cattle. Enslaved cowboys were often<br />

treated better than people working<br />

cotton in part because their skillset<br />

was more specialized and they were<br />

not easily replaced. They had access<br />

to better food, though they remained<br />

in bondage and were traded much<br />

like the livestock they saw after.<br />

24 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>

Cowboys<br />

BY ZEB<br />

LARSON<br />

Once the 13th Amendment<br />

permanently ended chattel<br />

slavery in the United States,<br />

many of the freemen put<br />

their skills to work by seeking<br />

employment as cowboys.<br />

Many of them remained with<br />

their former masters out of<br />

convenience, and compared to<br />

freed persons who had worked<br />

growing cotton, they enjoyed<br />

far better circumstances. Their<br />

labor was better compensated,<br />

especially because of the<br />

postwar demand for beef and<br />

the absence of white labor in<br />

places like Texas. In the Journal<br />

of Blacks in Higher Education,<br />

African American cowboys<br />

were estimated to be anywhere<br />

between a quarter and a third<br />

of the men who worked the<br />

famous Chisholm Trail. Part<br />

of the cowboy lifestyle in the<br />

South was born out of necessity:<br />

Southern states actively<br />

prevented freed slaves from<br />

purchasing land, and it was<br />

easier to work as a ranch hand<br />

than it was to try and become<br />

a farmer.<br />

The Wild West<br />

However, black cowboys did<br />

not remain confined to the<br />

South. The South was violent<br />

and repressive, and it only<br />

became more so with the end<br />

of Reconstruction and the<br />

return of white segregationist<br />

governments to power. Many<br />

cowboys headed out West to<br />

escape the suffocating racial<br />

mores of the South. To be sure,<br />

the West was no guaranteed<br />

safe haven for cowboys: plenty<br />

of white settlers had moved<br />

west precisely because they<br />

didn’t want to compete with<br />

African American laborers.<br />

However, cowboys could still<br />

leverage the skills that they<br />

had, and because many parts<br />

of the American West remained<br />

poorly settled, accepting their<br />

labor was a necessity.<br />

Defying the World<br />

The era of the Wild West<br />

produced several noteworthy<br />

African American cowboys,<br />

many of whom filled the role to<br />

the hilt. Nat Love, better known<br />

as Deadwood Dick, was born<br />

in Nashville, Tennessee into<br />

slavery. In 1870, he headed<br />

west and ended up in Dodge<br />

City, where he worked on<br />

cattle drives. He later headed<br />

further out west to Arizona.<br />

Like many cowboys, Dick liked<br />

to tell tall tales of his exploits:<br />

he claimed to have been an<br />

expert gunfighter, participated<br />

in cattle drives and<br />

rodeos, and liked to<br />

brag that he rode his horse into<br />

a saloon to order whiskey for<br />

the both of them.<br />

Regardless of how much of<br />

his life was the result of colorful<br />

embellishment, it’s clear<br />

he embraced the cowboy life<br />

because it offered a degree of<br />

freedom. In his autobiography<br />

The Life and Adventures of Nat<br />

Love, written in 1907, Love<br />

spelled out why he liked being<br />

a cowboy. “Mounted on my<br />

favorite horse, my long horsehide<br />

lariat near my hand, and<br />

my trusty guns in my belt…I felt<br />

I could defy the world.” He was<br />

respected among his fellow<br />

cowboys — black and white —<br />

and his employers trusted him.<br />

Rodeos and Riding<br />

The cowboy era of the Wild<br />

West was in decline after 1890<br />

because much of the West had<br />

either been settled or enclosed<br />

through barbed wire: ranchers<br />

no longer needed cowboys<br />

to take cattle on long drives.<br />

This did not mean the end<br />

of cowboy work for African<br />

Americans, however. Even as<br />

the cowboy tradition declined,<br />

its presence in the popular<br />

imagination grew, partly<br />

because of literature, music<br />

and attractions like rodeos or<br />

Wild West shows. The former<br />

showcased cowboy skills like<br />

riding and lassoing, while<br />

the latter helped to create the<br />

idea of the mythologized West<br />

through staged gunfights and<br />

trick shows.<br />

African American cowboys<br />

also helped to create the idea<br />

of a cowboy in the public<br />

imagination. Deadwood Dick<br />

allegedly got his name from<br />

participating in one such rodeo<br />

in the town of Deadwood,<br />

South Dakota (he also claimed<br />

to be a record-holder for breaking<br />

a horse in nine minutes).<br />

The African American cowboy<br />

Bill Pickett, also known as the<br />

Dusky Demon, was responsible<br />

for helping to invent<br />

another rodeo tradition: steer<br />

riding. Pickett was a cowboy<br />

in Oklahoma who invented a<br />

practice known as “bulldogging”<br />

to wrestle steers to the<br />

ground: he would jump from<br />

a horse, grab the steer by the<br />

horns, and bite it on the lip to<br />

force it to the ground. Pickett<br />

became famous and toured<br />

with the likes of Buffalo Bill<br />

Cody until his death in 1932.<br />

Today, the tradition of<br />

African American cowboys<br />

survives through rodeos and<br />

other public exhibitions. The<br />

Bill Picket Invitational Rodeo is<br />

an all-black touring rodeo that<br />

is now entering its 34th year<br />

of operations. Young cowboys<br />

are drawn to it for a variety<br />

of reasons. A young rider in<br />

Charleston, Mississippi told<br />

me how he got into riding:<br />

he wanted to impress a girl<br />

for prom by showing up on<br />

a horse. For him, riding a<br />

horse offers the same sense of<br />

tranquility it offered Nat Love:<br />

“It was kinda like a peace-ofmind,<br />

it was a runaway place<br />

from me. Just coming out of<br />

high school, trying to figure out<br />

life. It was a different feeling<br />

and I still use it as a runaway<br />

place. It’s just a peace place.<br />

The horse will get your mind<br />

out of whatever’s going on.”<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 25

Rising Tides<br />

Photographs by:<br />

Sean Gallagher<br />

Lauren Owens Lambert<br />

Michael O. Snyder<br />

26 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

With the sea levels expected<br />

to rise between 10 and 32<br />

inches or higher by the end of<br />

this century, more and more<br />

coastal communities are on<br />

the brink of living in limbo.<br />

According to the Internal<br />

Displacement Monitoring<br />

Centre in Geneva, Switzerland, 18.8 million<br />

disaster-related displacements happened<br />

in 2017. And while such displacements<br />

are linked to natural disasters, the worsening<br />

global warming could be the root<br />

cause. The World Bank also estimates that<br />

by 2050, 143 million people from Latin<br />

America, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan<br />

Africa alone would be forced to migrate due<br />

to climate crisis.<br />

Sean Gallagher’s exhibit, Tuvalu:<br />

Beneath the Rising Tide shows the expanse<br />

of this South Pacific nation island — how the<br />

seas are slowly consuming the land and the<br />

impact of strong water surges on the dwellings<br />

of 11,200 Tuvaluans. Lauren Owens<br />

Lambert’s Along the Waters Edge shows<br />

what melting ice in places like Antarctica<br />

does to regions like New England. While<br />

her exhibit, The Farmer and the<br />

Fishermen, displays how coastal communities<br />

adapt and change livelihoods. Michael<br />

O. Snyder, with his exhibit Eroding Edges,<br />

infuses emotions into still images showcasing<br />

the everyday lives of people in the US —<br />

how rising tides bring out hope, innovative<br />

solutions, and the human grit to keep pushing<br />

forward.<br />

Photo by Lauren Owens Lambert<br />

The farming crew of Merry Oysters handpick<br />

and load the boat during low tide on<br />

Duxbury Bay, Massachusetts in July. Scientists<br />

say ocean water has grown 30 percent more<br />

acidic since the Industrial Revolution and is<br />

on track to get worse in coming decades as<br />

it soaks up excess carbon dioxide from air.<br />

Although climate change poses challenges<br />

such as ocean acidification and increasing<br />

coastal storm intensity, the shellfish industry in<br />

Massachusetts is one of the fastest growing<br />

in the state. Shellfish such as oysters, scallops<br />

and mussels are not only a good source for<br />

local food, but because they are filter feeders,<br />

they also help clean the ocean.<br />

Not a subscriber? Click here to receive the print version of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 27

28 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Photo by Michael O. Snyder<br />

Jason Jones and Wade Murphy III raise<br />

the sails at dawn on the Rebecca T.<br />

Ruark, that, since 1886, has dredged<br />

oysters from the Chesapeake Bay of<br />

Maryland using only power from the<br />

wind. Oysters, once the cornerstone of<br />

the regional economy, have declined<br />

by more than 98% since colonial times.<br />

Despite a recent comeback, the oyster<br />

stocks, and the watermen who depend<br />

on them, remain threatened by changing<br />

temperatures and rising tides.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 29

30 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Photo by Sean Gallagher<br />

<strong>Fall</strong>en trees in the shallows of<br />

Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu. Erosion<br />

of land is an inevitable consequence<br />

of life in a coral atoll<br />

nation. As sea levels rise and<br />

increased threats from storm<br />

surges and extreme weather<br />

events occur, the land of Tuvalu<br />

will increasingly become fragile<br />

and prone to erosion.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 31

Photo by Sean Gallagher<br />

Children play in an abandoned<br />

home in central Funafuti. The<br />

Pacific island nation has seen<br />

an exodus of people who have<br />

already fled to countries such<br />

as New Zealand and Australia<br />

in search of better economic<br />

opportunities and less environmental<br />

threats.<br />

32 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 33

Photo by Lauren Owens<br />

Lambert<br />

Communities developed on<br />

barrier beaches such as Plum<br />

Island, on the north shore of<br />

Massachusetts, are particularly<br />

vulnerable to coastal erosion<br />

and major flooding from storm<br />

surges and will continue to<br />

face the challenges of climate<br />

change. “Don’t build here if<br />

you’re afraid of losing your<br />

house,” says longtime resident<br />

Verne Fisher.<br />

34 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 35

Photo by Lauren Owens<br />

Lambert<br />

In June 2016, community<br />

organizer Magdalena Ayed, a<br />

resident in East Boston, looks<br />

out over her neighborhood<br />

that is at risk of flooding from<br />

the effects of climate change.<br />

She says she’s happy that city<br />

officials and some developers<br />

are starting to take climate<br />

change seriously.<br />

36 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 37

By Tammy Danan<br />

“We used to be able<br />

to catch fish right from<br />

under our houses,” says<br />

Rogelio Alburo, a local<br />

fisherman from Davao<br />

City.<br />

Photos, L to R:<br />

Arka Dutta, from Evanescing Waters,<br />

Whisking Water.<br />

Lauren Owens Lambert, from Along<br />

the Waters Edge<br />

David Verberckt, from Source of Life<br />

Saud A. Faisal, from Water Prisoners<br />

RISINGTIDES<br />

Located on the southern part<br />

of the Philippines, most<br />

houses in the country’s<br />

coastal communities are on<br />

wooden stilts. I was sitting<br />

outside his neighbor’s house<br />

joined by other fisherfolks and<br />

their wives, and as Rogelio<br />

reminisced about the 1970s<br />

when the sea was still rich,<br />

he also noted how today’s<br />

conditions are hurting fishermen.<br />

“I don’t remember exactly<br />

when the water started rising,<br />

but there was a time when we<br />

were getting fewer and fewer<br />

fish,” he said.<br />

Today, coastal road development<br />

in the city that swept<br />

away hundreds of houses adds<br />

to the burden. Now, fishermen<br />

like Rogelio juggle multiple jobs<br />

to provide basic needs for their<br />

families. And for a country with<br />

over 7,000 islands, Rogelio<br />

and his neighbors are not the<br />

only ones changing their livelihood<br />

as the country’s coastal<br />

communities experience the<br />

rising waters.<br />

Clear As Can Be<br />

A report published by NASA<br />

in 2018 shows that the rate of<br />

global sea level rise has been<br />

accelerating in recent decades.<br />

The melting of sea ice in Antarctica<br />

and Greenland due to<br />

climate change is among the<br />

culprits.<br />

Dr. Simon Engelhart, an<br />

associate professor at the<br />

University of Rhode Island<br />

Geosciences Department, said<br />

that the distribution of water<br />

on the surface of the earth also<br />

plays a part. “Features such<br />

as ocean currents (e.g. the<br />

Gulf Stream) and multi-year to<br />

decadal variability within the<br />

system (e.g., El Niño/La Niña)<br />

can change the distribution of<br />

water and cause increasing or<br />

decreasing sea levels.” That<br />

said, if the Gulf Stream off the<br />

coast of the US slows down,<br />

then more water flows towards<br />

the US East Coast and there<br />

will be faster rising sea levels.<br />

And during El Niño/La Niña,<br />

water levels in the Pacific can<br />

change in the space of months<br />

to years by nearly a foot.<br />

Land, Water, and<br />

Climate Refugees<br />

As a result, many countries<br />

in the Pacific region are now<br />

feeling the impact. And those<br />

in coastal communities are the<br />

first to take the heat.<br />

Lawrence Nodua is a<br />

38 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>

esident of Reef Islands in the<br />

Solomon Islands. “Life in the<br />

coastal communities are more<br />

[reliant] on fishing and few on<br />

gardening,” he shared. But<br />

because of the water’s rising<br />

temperatures, the fish could<br />

hardly survive as hot water<br />

holds less oxygen. Add to that<br />

the fact that the current has<br />

become more confusing than<br />

ever, fishermen can no longer<br />

predict the best time to set<br />

sail. As a result, they spend<br />

more time in the sea than ever<br />

before. Coral reefs in Solomon<br />

Islands are also affected, and<br />

as corals die, the fish lose their<br />

breeding ground.<br />

In a 2010 study conducted<br />

by Nodua, it appeared that<br />

internal migration in Solomon<br />

Islands has increased in the past<br />

two decades. Residents from<br />

smaller islands such as Tikopia<br />

and Duff move to larger islands<br />

like Utupua, Santa Cruz, and<br />

Vanikoro. But even this is not a<br />

permanent solution. Nodua’s<br />

research revealed that the<br />

Solomon Islands has a much<br />

bigger problem — a problem<br />

shared by other nations like<br />

Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Tuvalu,<br />

and Maldives — coastal erosion.<br />

Dr. Engelhart has an explanation<br />

for this. He says, “when<br />

we talk about rising water levels,<br />

we use the term ‘relative sea<br />

level’ because we can change<br />

the level of the sea that people<br />

experience by either changing<br />

the volume/distribution of water<br />

or by changing the elevation<br />

of the land with respect to the<br />

ocean. Therefore, if the land is<br />

subsiding, sea level will rise in<br />

the eyes of an observer on that<br />

subsiding land even if the ocean<br />

volume isn’t changing.”<br />

And while most people think<br />

coastal erosion is simply caused<br />

by waves and tides washing<br />

away the land, Dr. Engelhart<br />

highlighted the role of tectonics,<br />

saying it’s one of the long-term<br />

processes that can alter the land<br />

level. “Earth’s tectonic plates<br />

moving past each other and<br />

getting stuck and then releasing<br />

make the land elevation change.<br />

These land-level changes can be<br />

slow and happen over hundreds<br />

to thousands of years but also<br />

can happen quickly where as<br />

much as a couple of meters<br />

elevation change can happen<br />

in seconds to minutes when a<br />

large earthquake occurs such as<br />

occurred in Sumatra in 2004 or<br />

Japan in 2011.”<br />

Health at Risk<br />

While conducting his study,<br />

Nodua found out that the<br />

climate crisis does have massive<br />

effects on food security.<br />

Residents of the Tuo village in<br />

Reef Islands have seen how the<br />

prolonged dry weather causes<br />

root crops and fruit trees to<br />

bear less. In late 2004 to early<br />

2005, Reef Islanders’ staple<br />

food ran low. The rising waters<br />

cause swamps to become more<br />

saline, making it difficult to<br />

grow swamp taro, a common<br />

food in most countries in<br />

Southeast Asia.<br />

As a domino effect, this<br />

problem further affects the<br />

health of islanders not only in<br />

Solomon Islands but coastal<br />

communities in Southeast Asia<br />

and globally. The challenge of<br />

harvesting fruits due to unstable<br />

weather patterns, and the<br />

decline of food sources puts<br />

children at risk of health and<br />

nutritional problems.<br />

Today, We Think. And<br />

Think Better.<br />

Islanders from different parts of<br />

the globe may have historically<br />

learned to embrace their<br />

environment. They may have<br />

learned how to understand<br />

the waters and everything it<br />

brings and takes. But now it<br />

seems the rising waters and the<br />

global climate have changed<br />

its language.<br />

Crosses and bones are<br />

being washed away, leaving<br />

people in Solomon Islands with<br />

no decent place to bury their<br />

dead. Nodua, who now works<br />

closely with Oceans Watch<br />

Solomon Islands, also found<br />

that the rising sea is affecting<br />

the access to fresh water in villages<br />

like Tuo; their well water<br />

started tasting saltier in the<br />

early 1990s.<br />

In the Philippines, the wives<br />

of fisherfolks have their own<br />

battle. Jenelyn Caro Quintalla<br />

comes from a family of 16. Her<br />

parents raised them all through<br />

fishing. Today, Jenelyn is a<br />

mother to six and her husband<br />

is also a fisherman. But as<br />

coastal road development eats<br />

through their community, and<br />

the waters continue to change<br />

temperature, Jenelyn sometimes<br />

finds herself wide awake at<br />

night. “It’s not easy. I feel like<br />

our life is in limbo. We can’t<br />

fish anymore so my husband<br />

works part-time at a construction<br />

site; budgeting is always a<br />

challenge,” she shared.<br />

RESOURCES<br />

Oceans Watch Solomon Islands<br />

www.oceanswatch.org/oceanswatchsolomon-islands<br />

Mother Nature Cambodia<br />

www.mothernaturecambodia.org<br />

Pacific Climate Warriors<br />

www.350pacific.org/pacific-climate-warriors<br />

Greenpeace<br />

www.greenpeace.org<br />

Pacific Community<br />

www.spc.int<br />

National Oceanic and<br />

Atmospheric Administration<br />

https://coast.noaa.gov<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 39

Aesthetics of DOCUM<br />

Why good pictures of bad things matter<br />

Why is it that the documentary<br />

photography community<br />

is obsessed with<br />

seeking really good photographs<br />

about really bad<br />

things that the human race<br />

brings upon each other? It is the core principal<br />

of the Social Documentary Network<br />

(SDN), <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine and other similar<br />

organizations. While we are driven to<br />

defend victims of human rights abuses (an<br />

admirable goal), why do we place such<br />

a premium on images that present such<br />

abuse, or in some cases solutions, in a<br />

highly aestheticized manner?<br />

With SDN, we have competitions<br />

with respected jurors, all whom pour<br />

over visual stories of the human condition<br />

to select the one that is the most<br />

40 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong><br />

original, well-crafted, thoughtfully<br />

composed, and addressing something<br />

that the public deserves to know more<br />

about and possibly act on. But it is those<br />

photographs that are most aesthetically<br />

successful that win the awards.<br />

Much has been written by me and<br />

others about photographers giving voice<br />

to the voiceless, using powerful photography<br />

to inspire action, shining a light<br />

in dark places and other similar noble,<br />

if not canned, responses. Perhaps it is<br />

that artists (in this case documentary<br />

photographers) use their strengths to<br />

challenge injustices in the same way<br />

writers, poets, playwrights, and activists<br />

use the strengths they have to achieve<br />

similar outcomes. But I believe there is<br />

more to it.<br />

Photo by Maryam Ashrafi from her SDN exhibit, Mourning<br />

Kobané. A YPJ fighter looks over the wreckage left by<br />

fighting on a street in Kobané, Syria, March 2015.<br />

An Obsession with Aesthetics<br />

Why are we obsessed with aesthetics<br />

when aesthetics really has little to do<br />

with the problem or solution? Would all<br />

these resources be better spent if instead<br />

we were out on the streets demanding<br />

action?<br />

I believe the answer to our obsession<br />

with, or commitment to, aesthetics lies<br />

somewhere in the following explanations.<br />

One is that the media knows that to<br />

gain readers and viewers, they must<br />

provide interesting and complex images<br />

that only an inspired photographer can<br />

deliver. Otherwise what remains is a<br />

dense page of grey type that will neither<br />

sell content nor attract advertisers. But

ENTARY<br />

WHY GOOD PICTURES OF<br />

BAD THINGS MATTER<br />

By Glenn Ruga<br />

more significantly, a text-heavy factual<br />

account will only draw the scholarly,<br />

intellectually curious, or the activist<br />

and not the ubiquitous everyman/<br />

everywoman with a job, children, rent/<br />

mortgage, and driven towards stability<br />

for themselves and their family. The<br />

majority of people on our planet don’t<br />

have the time nor the mental capacity to<br />

engage, but might pay attention when<br />

their sensibility is stopped in its tracks by<br />

a photo such as the Syrian child Aylan<br />

Kurdi dead on a beach in Turkey.<br />

The second reason I believe gets to<br />

a more fundamental issue. The human<br />

race is capable of the basest and ugliest<br />

actions as evidenced by the many genocides<br />

(loosely defined) committed just in<br />

the last hundred years (the Holocaust,<br />

Armenia, Rwanda, Cambodia,<br />

Indonesia, Sudan, Darfur, Bosnia, Syria,<br />

DRC, Rohingya, etc.) But the human race<br />

is also capable of great heights of intellectual,<br />

emotional, physical, cultural, and<br />

magical achievements such as love, birth,<br />

Mozart, Bob Dylan, Martin Luther King,<br />

NASA, Pablo Picasso, Pablo Casals,<br />

Billie Holiday, Nelson Mandela, Vincent<br />

Van Gough, Serena and Venus Williams,<br />

Henri Cartier Bresson, Toni Morrison<br />

as well as the drawings of children the<br />

world over.<br />

Acts of Defiance<br />

For all who strive for beauty in the face<br />

of suffering, it is an act of defiance<br />

against those who bring misery on<br />

this planet, and what is a more perfect<br />

example than an artist striving for perfection<br />

where misery abounds.<br />

In her exhibit on SDN titled Mourning<br />

Kobané, Paris-based Iranian photographer<br />

Maryam Ashrafi made this stunning<br />

photograph of a young woman who,<br />

along with members of YPJ (Women’s<br />

Protection Units), “mourn during the<br />

ceremony for Ageri, their fellow fighter,<br />

who was killed during clashes with<br />

Islamic State in Eastern frontline of<br />

Kobané, Syria.” This photograph is not<br />

of dead comrades or headless victims of<br />

the despicable Islamic State. Rather it is<br />

a stunning portrait shot not in a studio<br />

with lights and assistants but rather<br />

under challenging conditions during a<br />

funeral wrought with intense emotions<br />

and under constant fear of attack. The<br />

young woman’s eyes, her gaze, her colorful<br />

scarf and military fatigues, the soft<br />

blue sky and horizon line so thoughtfully<br />

placed, the woman on the left side of the<br />

frame, possibly injured in battle, all create<br />

a stunning work of art. How can one<br />

not be moved by this? What happened?<br />

Who are the YPJ (a heroic story unto<br />

itself)? The photo is a weapon against<br />

the horrors of the Islamic State. Its secondary<br />

target is all who say that women<br />

cannot engage and triumph in battle.<br />

The power of this beautiful photo of a<br />

Kurdish warrior I hope has launched a<br />

thousand people to join her struggle to<br />

save the Kurdish and other residents of<br />

Kobané from ISIS. (nb. Sarina, the subject<br />

of this photo, was martyred in battle<br />

in the fall of 2018.)<br />

Kurdish photographer Younes<br />

Mohammad has extensively photographed<br />

the wars and carnage in Iraq<br />

Photo by Younes Mohammad. Mosul, Iraq: A man from<br />

the Ghadesiya neighborhood was wounded during the battle<br />

for Mosul by a suicide ISIS car bomb. He was rescued and<br />

treated by medics of the Iraqi army in a field clinic.<br />

and Syria. His portfolio includes some<br />

very graphic images of bodily destruction<br />

caused by war. But it is not the gore<br />

that makes him a great photographer,<br />

rather it is his photographs of the passion,<br />

tenacity, and emotional depths of<br />

his subjects amidst such horrible conditions<br />

that have lasting value. His photograph<br />

in his SDN exhibit on the battle<br />

for Mosul, In Less than an Hour, of a<br />

man from the Ghadesiya neighborhood<br />

wounded during the battle for Mosul by<br />

a suicide ISIS car bomb, is a stunning<br />

example of a great photo made during<br />

battle. The young man (by the caption<br />

we assume he survives) has the look of<br />

calmness while medics are rushing into<br />

action. The photograph makes interesting<br />

use of color (blue latex gloves, blue<br />

jacket liner, and contrasting yellow plastic<br />

stretcher) and strong linear elements<br />

of the medics’ arms and the aluminum<br />

frame of the gurney, all pointing toward<br />

the central subject—the wounded soldier<br />

who lays calm amid chaos. Younes reassures<br />

us that although chaos reigns on<br />

the battlefield, it has not destroyed our<br />

soul as a species.<br />

Turning to other parts of the world<br />

and other issues, the SDN website has<br />

Not a subscriber? Click here to receive the print version of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 41

Photo by David Verberckt. from his SDN exhibit, Waiting for the Rain. One of the 4,500 displaced persons living near<br />

the capital of Somaliland. Tens of thousands of pastoralists have lost all their livestock during the past drought and became<br />

fully dependent on humanitarian aid for their subsistence. Most have abandoned their nomadic way of life and settled into<br />

makeshift camps where aid and food can reach them.<br />

hundreds of exhibits of stunning photographs<br />

that focus our attention on<br />

challenging situations. David Verberckt<br />

is a Belgium photographer whose interest<br />

is to document and work closely with<br />

people whose destinies are marred by<br />

social and political injustices. His recent<br />

exhibit on SDN, Waiting for Rain, is<br />

about climate refugees from Somaliland<br />

who have lost their livestock due to a<br />

drought made worse by a changing<br />

climate. The opening photo is one of<br />

the 4,500 displaced persons living near<br />

the capital of Somaliland, now fully<br />

dependent on humanitarian aid for their<br />

subsistence. Most have abandoned their<br />

nomadic way of life and have settled<br />

in makeshift camps where aid and<br />

food can reach them. This is a powerful<br />

frontal portrait of a woman looking<br />

intensely in our eyes. There is no question<br />

of her disappointment in her current<br />

situation as a refugee. But she is not a<br />

faceless victim. She is wearing a beautiful<br />

turquoise scarf and earth-colored<br />

head covering. Her expression is not of<br />

pathos but rather the expression we may<br />

see in our own mothers the world over,<br />

an expression of familiarity, compassion,<br />

and fate. Verberckt uses the simple but<br />

effective visual tool of selective focus—<br />

the woman’s face is in sharp focus while<br />

the background recedes into blur. This<br />

may be a textbook example of how to<br />

make a good portrait, but combined<br />

with the colors, the intense lighting<br />

across the woman’s face, how her head<br />

and shoulders so perfectly fill the frame,<br />

the sweep and rhythms of shadows starting<br />

in the lower left and ending with her<br />

black headband, the bokeh (Google the<br />

term if you are unfamiliar with it) of the<br />

shadows, makes this a lasting comment<br />

on how the human species has defiled<br />

our planet yet how we resist by being<br />

responsible stewards and take decisive<br />

action to remedy the situation. It is also<br />

a statement on how the human soul<br />

(both the subject’s and Verberckt’s) lives,<br />

struggles, and perseveres.<br />

Meaning Can Heal<br />

Humanity does not always win. In some<br />

cases, the horrors are so great, the<br />

perpetrators so debased, the victims so<br />

broken, that it is not clear if the species<br />

will survive. There are no comforting<br />

photographs from the Holocaust, from<br />

Rwanda, nor from other existential genocides<br />

in history. During the Holocaust,<br />

there was much art created by inmates<br />

of concentration camps, but it doesn’t<br />

reassure us. Rather the images makes us<br />

question if God, or the human species<br />

as we know it, can continue to exist<br />

following the Holocaust? Viktor Frankl,<br />

an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist<br />

who lost his whole family during the<br />

Nazis’ attempt to exterminate the Jews,<br />

counseled his fellow prisoners with a<br />

philosophy that argued that striving<br />

for meaning, not pleasure nor power,<br />

is what keeps us alive. Frankl was not<br />

an artist, but in the throes of the worst<br />

horrors faced by humanity, he invoked<br />

the only thing left to camp prisoners facing<br />

a near-certain death—a belief that<br />

finding meaning can heal. Is that not<br />

what artists the world over, and certainly<br />

photographers, are always striving to<br />

insist on? That amidst chaos, meaning<br />

can prevail.<br />

I can go on with equally as powerful<br />

photographs on SDN and elsewhere<br />

addressing equally as critical global<br />

situations, but the question remains<br />

“so what?” What effect does David<br />

Verberckt’s photos have on either global<br />

climate change or the specific situation<br />

of displaced pastoralists in Somaliland?<br />

What effect does Maryam Ashrafi’s<br />

photos from Kurdistan have on defeating<br />

ISIS? I hope their photos appear in venues<br />

with greater readership than either<br />

SDN or <strong>ZEKE</strong> magazine. I hope people<br />

will see these images and perhaps gain<br />

greater insight and empathy for victims<br />

of climate change or ISIS, and perhaps<br />

be driven to action. But I also believe<br />

that David Verberckt, Maryam Ashrafi,<br />

Younes Mohammad, and tens of thousands<br />

of photographers the world over<br />

who have made great personal sacrifices<br />

and have worked tirelessly to make<br />

great photos, have themselves taken a<br />

stand against complacency because<br />

they have been anything but complacent.<br />

They, as any artist does, make<br />

us confront a basic fact that amid so<br />

much suffering in the world, there is also<br />

beauty. But beauty is not separate from<br />

suffering. On the contrary, perfection<br />

and beauty gives us hope that things<br />

can be different and better, that we can<br />

rally, we are an intelligent species, and<br />

we can rise from the ashes to heal.<br />

42 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>

Contributors<br />

Photographers<br />

Carol Allen-Storey, based in the UK, is<br />

an award-winning documentary photographer<br />

chronicling humanitarian and social<br />

issues. In 2009, Storey was appointed as a<br />

UNICEF ambassador for photography. She<br />

sits on the boards of the AOP (Association<br />

of Photographers), and the BPPA (British<br />

Professional Press Association). She is a<br />

founding member of the World Photography<br />

Academy for the SONY Award. Some of her<br />

clients include: UNICEF, Save The Children,<br />

The Elton John AIDS Foundation, WWF,<br />

International Alert, Comic Relief, Royal British<br />

Legion, The Global Fund for Children.<br />

Toby Binder was born in Germany and studied<br />

at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and<br />

Design. He focuses his photography on social,<br />

environmental and political topics. Now based<br />

in Argentina and Germany, he works on projects<br />

on post-war and crisis situations as well as<br />

the daily life of people. He has been awarded<br />

internationally the Nannen-Preis in 2017, the<br />

Sony World Photo Awards in 2017 and <strong>2019</strong>,<br />

and the Philip-Jones-Griffiths-Award in 2018.<br />

The same year he received an Honorable<br />

Mention at the UNICEF Photo of the Year.<br />

Rory Doyle is based in Cleveland,<br />

Mississippi. Born and raised in Maine, he<br />

moved to the South in 2009 and has remained<br />

committed to the region ever since. His work<br />

often highlights unique Southern subcultures<br />

commonly overlooked. Doyle is a 2018<br />

Mississippi Visual Artist Fellow through the<br />

Mississippi Arts Commission and National<br />

Endowment for the Arts for “Delta Hill Riders.”<br />

He won the 16th Annual Smithsonian Photo<br />

Contest for the project in <strong>2019</strong> and the<br />

Southern Prize from South Arts organization. He<br />

was also recognized for the project by winning<br />

the <strong>2019</strong> Zeiss Photography Award, and the<br />

photojournalism category at the 2018 Eye Em<br />

Awards in Berlin, Germany.<br />

Sean Gallagher is a British photographer<br />

and filmmaker now based in Asia. His work<br />

focuses on highlighting environmental issues<br />

in the Asia-Pacific region. With a degree in<br />

zoology, his background in science has led<br />

to communicating ecological issues through<br />

visual storytelling. He is a 7-time recipient of<br />

the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting travel<br />

grant and his images are represented by the<br />

National Geographic Image Collection. He is a<br />

Fellow of the UK Royal Geographical Society,<br />

the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute<br />

Science Journalism Program and the Resilience<br />

Journalism Fellowship at the Craig Newmark<br />

Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.<br />

Lauren Owens Lambert is a photojournalist<br />

based in the Boston area focusing on<br />

documenting the human aspect of conservation,<br />

climate change, and ocean science. She<br />

is an International League of Conservation<br />

Photographer - Emerging League and a contributing<br />

photographer with Everyday Extinction<br />

and a Blue Earth Alliance project photographer.<br />

She has curated and shown in exhibitions at<br />

Photoville and has presented work at the UN on<br />

the importance of visual storytelling under the<br />

Sustainable Development Goal 14 – Life Below<br />

Water.<br />

Michael O. Snyder is a photographer and<br />

filmmaker whose work sits at the intersection<br />

of environmental sustainability and social<br />

justice. He has spent the past 15 years working<br />

on projects in the Amazon, the Arctic, the<br />

Himalaya, Asia, East Africa, and his home in<br />

rural Appalachia. His work features intimate<br />

portraiture of cultures affected by environmental<br />

issues, with a focus on empowerment and<br />

community-driven solutions.<br />

Writers<br />

Barbara Ayotte has served as a senior<br />

strategic communications strategist, writer<br />

and activist for leading global health, human<br />

rights and public media nonprofit organizations,<br />

including the Nobel Peace Prize- winning<br />

Physicians for Human Rights and International<br />

Campaign to Ban Landmines. Barbara is SDN’s<br />

Communications Director and is Editor of <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

magazine.<br />

Alessandra Bergamin is an Australian<br />

freelance journalist whose work focuses on<br />

immigration, public health, and environmental<br />

justice. She has been published in National<br />

Geographic, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and<br />

Literary Hub, among others. She also produces<br />

short documentaries and often photographs her<br />

stories. She is a <strong>2019</strong> UC Berkeley Food and<br />

Farming Fellow.<br />

Caterina Clerici is an Italian freelance<br />

journalist and producer based in New York. She<br />

was awarded three Innovation in Development<br />

Reporting Grants from the European Journalism<br />

Centre for her multimedia work in Haiti, Ghana<br />

and Rwanda, published in TIME, The Guardian,<br />

Al Jazeera English and Marie Claire, among<br />

others. She worked as a freelance photo editor<br />

and producer for VR at TIME, and as an executive<br />

video producer at Blink.la.<br />

Tammy Danan is a freelance storyteller<br />

based in the Philippines. While a generalist,<br />

she aims to better focus on social issues and<br />

humanitarian crises, with a stress on the plight<br />

of the Filipino indigenous people. In constant<br />

collaboration with photographers, her words<br />

have appeared in Al Jazeera, VICE, Audubon.<br />

org, OZY and others.<br />

Lori Grinker is a photographer, filmmaker,<br />

artist, and educator. Author of Afterwar;<br />

Veterans from a World in Conflict; co-author,<br />

The Invisible Thread; Mike Tyson; and Six<br />

Days From Forty (in progress). Her work is<br />

represented by the Nailya Alexander Gallery<br />

in NYC, and is in many private and public<br />

collections including the ICP; Museum of Fine<br />

Arts, Houston; and the Museum of Modern<br />

Art. Awards include a New York Foundation<br />

for the Arts Grant; W. Eugene Smith Memorial<br />

Fellowship; Ernst Hass Grant; Open Society<br />

Community Engagement Grant; and the World<br />

Press Foundation. She is an Ochberg Fellow of<br />

the Dart Center on Journalism and Trauma, and<br />

a senior member of Contact Press Images.<br />

Zeb Larson is a writer and researcher based<br />

in Columbus, OH. He recently finished a PhD<br />

in History at Ohio State University. His research<br />

deals with the global anti-apartheid movement,<br />

and he has begun working on adapting his dissertation<br />

into a book.<br />

Glenn Ruga is the Executive Editor of <strong>ZEKE</strong><br />

magazine and founder and director of the<br />

Social Documentary Network (SDN). From<br />

2010-2013, he was the Executive Director of<br />

the Photographic Resource Center. From 1995-<br />

2007 he was the Director, and then President,<br />

of the Center for Balkan Development. Ruga is<br />

also the owner and creative director of Visual<br />

Communications, a graphic design firm located<br />

in Concord, MA.<br />

J. Sybylla Smith is an independent curator<br />

with more than 25 solo or group exhibitions<br />

featuring over 80 international photographers<br />

exhibited in the US, Mexico, and South<br />

America. An adjunct professor, guest lecturer,<br />

and thesis advisor, Sybylla has worked with the<br />

School of Visual Arts, the School of the Museum<br />

of Fine Arts, Wellesley College, and Harvard<br />

University.<br />

Frank Ward is a professor of visual art at<br />

Holyoke Community College, Holyoke, MA. In<br />

2016, Ward received a National Endowment<br />

for the Humanities grant and a Mass Humanities<br />

grant for his photography of Holyoke, MA. In<br />

2012, he went to Central Asia as the Cultural<br />

Envoy in Photography for the US Department<br />

of State. In 2011, he was awarded an Artist<br />

Fellowship from the Massachusetts Cultural<br />

Council for his photography in the former Soviet<br />

Union. He has also received support for his<br />

work in the former Yugoslavia, Tibet and India.<br />

He is represented by Photo Eye Gallery in Santa<br />

Fe, NM.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 43

44 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

Out of the Shadows<br />

Shamed Teen Mothers in Rwanda<br />

By Carol Allen-Storey<br />

An epidemic of teen pregnancies is<br />

permeating the population in Rwanda.<br />

Vulnerable girls as young as 13<br />

find themselves in this unwarranted<br />

circumstance. Many as a result of<br />

rape and others through ignorance of<br />

engaging in sexual activities without protection,<br />

nor any knowledge of the responsibility<br />

of motherhood. The fathers run away. The<br />

young mothers bring shame to the family, are<br />

isolated and abandoned. These emotionally<br />

damaged adolescents have assumed the awesome<br />

responsibility of being mothers when<br />

they are still children. The aim of this essay<br />

is to give voice to these damaged girls and<br />

attract wider support for them to live their lives<br />

with dignity. Hope for Rwanda, a local charity,<br />

is providing support through counselling,<br />

legal aid and skills training.<br />

“I was finishing my last year in school<br />

and became pregnant. I was horrified,<br />

I wanted to abort, as I would<br />

be forced to leave school. My future<br />

would be dim. After I could not raise<br />

the fees for abortion, I felt my only<br />

option was to commit suicide. My<br />

friend told my mother of my situation<br />

and she said; ‘Since I sinned once<br />

by getting pregnant I should not sin<br />

again’. After the baby was born I<br />

initially felt a deep sense of loneliness,<br />

but as I fell into my role I also learned<br />

to be responsible and strong.”<br />

Olive, 20. Daughter Giselle, 2.<br />

Carol Allen-Storey, based in the UK, is an<br />

award-winning photojournalist specializing in<br />

chronicling complex humanitarian and social<br />

issues. Her imagery illuminating people’s<br />

dignity and quest for survival reflects the<br />

unique trust and respect she engenders with<br />

her subjects.<br />

Storey’s work has been exhibited and<br />

published extensively. Installations of her photography<br />

appear in corporate headquarters<br />

and commercial premises. In October 2009,<br />

she was appointed a UNICEF ambassador for<br />

photography. Her recent prize money for winning<br />

gold in the Act of Kindness Award was<br />

donated to a small AIDS charity in Uganda<br />

because she believes it was morally responsible<br />

to donate the money back to those most<br />

in need.<br />

Not a subscriber? Click here to receive the print version of <strong>ZEKE</strong>.<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 45

46 / <strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong> 2015

“I became pregnant when I was 15 in<br />

a rush of passion with my boyfriend. I<br />

then thought about the fate of my life, I<br />

was not prepared for parenting, I lost<br />

hope. I told my boyfriend, he said he<br />

would support me, but soon after he<br />

vanished. I returned to my studies with<br />

the support of Hope for Rwanda, a<br />

local charity that has taught me to be a<br />

strong woman and built my confidence.<br />

Recently I became a mentor to other<br />

silly girls like me, who learn about the<br />

perils of being fooled by men when<br />

they request sexual favors and take<br />

no responsibility. When I complete my<br />

studies, my aim is to become a journalist<br />

on radio and TV.”<br />

Florence, 19. Brian William, 3<br />

<strong>ZEKE</strong> APRIL FALL <strong>2019</strong>/ 2015/ 47

“When I was a 17, I dated a<br />

man a lot older than me. Soon<br />

after a short affair I fell pregnant.<br />

When I confronted the father of<br />

the child, he said he had no interest<br />

in taking responsibility and knew<br />

I couldn’t afford the DNA test to prove<br />

his paternity. I wanted to commit suicide<br />

because I couldn’t see a future. Now I<br />

dream of being a journalist to give a<br />

voice to girls like me that have brought<br />

shame to their family and fall into depression<br />

as they feel their lives have been crushed<br />

by becoming pregnant and raising a child as<br />

a single mother.”<br />