The Vision Project

Throughout 2019, Developing Health & Independence (DHI), have been marking their 20th anniversary as a charity by looking to the future. Through articles, events and podcasts, they've asked people to answer the question of how we can achieve their vision of ending social exclusion. This collection of articles includes the contributions of experts from across public life and the political spectrum.

Throughout 2019, Developing Health & Independence (DHI), have been marking their 20th anniversary as a charity by looking to the future. Through articles, events and podcasts, they've asked people to answer the question of how we can achieve their vision of ending social exclusion. This collection of articles includes the contributions of experts from across public life and the political spectrum.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

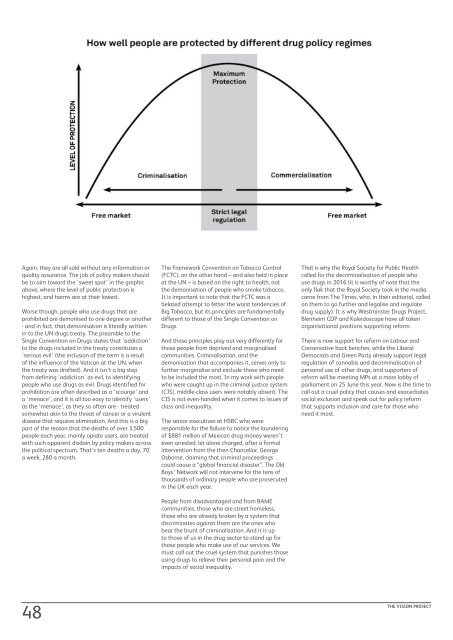

Again, they are all sold without any information or<br />

quality assurance. <strong>The</strong> job of policy makers should<br />

be to aim toward the ‘sweet spot’ in the graphic<br />

above, where the level of public protection is<br />

highest, and harms are at their lowest.<br />

Worse though, people who use drugs that are<br />

prohibited are demonised to one degree or another<br />

- and in fact, that demonisation is literally written<br />

in to the UN drugs treaty. <strong>The</strong> preamble to the<br />

Single Convention on Drugs states that ‘addiction’<br />

to the drugs included in the treaty constitutes a<br />

‘serious evil’ (the inclusion of the term is a result<br />

of the influence of the Vatican at the UN, when<br />

the treaty was drafted). And it isn’t a big step<br />

from defining ‘addiction’ as evil, to identifying<br />

people who use drugs as evil. Drugs identified for<br />

prohibition are often described as a ‘scourge’ and<br />

a ‘menace’, and it is all too easy to identify ‘users’<br />

as the ‘menace’, as they so often are - treated<br />

somewhat akin to the threat of cancer or a virulent<br />

disease that requires elimination. And this is a big<br />

part of the reason that the deaths of over 3,500<br />

people each year, mainly opiate users, are treated<br />

with such apparent disdain by policy makers across<br />

the political spectrum. That’s ten deaths a day, 70<br />

a week, 280 a month.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Framework Convention on Tobacco Control<br />

(FCTC), on the other hand – and also held in place<br />

at the UN – is based on the right to health, not<br />

the demonisation of people who smoke tobacco.<br />

It is important to note that the FCTC was a<br />

belated attempt to fetter the worst tendencies of<br />

Big Tobacco, but its principles are fundamentally<br />

different to those of the Single Convention on<br />

Drugs.<br />

And those principles play out very differently for<br />

those people from deprived and marginalised<br />

communities. Criminalisation, and the<br />

demonisation that accompanies it, serves only to<br />

further marginalise and exclude those who need<br />

to be included the most. In my work with people<br />

who were caught up in the criminal justice system<br />

(CJS), middle-class users were notably absent. <strong>The</strong><br />

CJS is not even-handed when it comes to issues of<br />

class and inequality.<br />

<strong>The</strong> senior executives at HSBC who were<br />

responsible for the failure to notice the laundering<br />

of $881 million of Mexican drug money weren’t<br />

even arrested, let alone charged, after a formal<br />

intervention from the then Chancellor, George<br />

Osborne, claiming that criminal proceedings<br />

could cause a “global financial disaster”. <strong>The</strong> Old<br />

Boys’ Network will not intervene for the tens of<br />

thousands of ordinary people who are prosecuted<br />

in the UK each year.<br />

People from disadvantaged and from BAME<br />

communities, those who are street homeless,<br />

those who are already broken by a system that<br />

discriminates against them are the ones who<br />

bear the brunt of criminalisation. And it is up<br />

to those of us in the drug sector to stand up for<br />

those people who make use of our services. We<br />

must call out the cruel system that punishes those<br />

using drugs to relieve their personal pain and the<br />

impacts of social inequality.<br />

That is why the Royal Society for Public Health<br />

called for the decriminalisation of people who<br />

use drugs in 2016 (it is worthy of note that the<br />

only flak that the Royal Society took in the media<br />

came from <strong>The</strong> Times, who, in their editorial, called<br />

on them to go further and legalise and regulate<br />

drug supply). It is why Westminster Drugs <strong>Project</strong>,<br />

Blenheim CDP and Kaleidoscope have all taken<br />

organisational positions supporting reform.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is now support for reform on Labour and<br />

Conservative back benches, while the Liberal<br />

Democrats and Green Party already support legal<br />

regulation of cannabis and decriminalisation of<br />

personal use of other drugs, and supporters of<br />

reform will be meeting MPs at a mass lobby of<br />

parliament on 25 June this year. Now is the time to<br />

call out a cruel policy that causes and exacerbates<br />

social exclusion and speak out for policy reform<br />

that supports inclusion and care for those who<br />

need it most.<br />

48<br />

THE VISION PROJECT