You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

BIRDS IN BRITISH CULTURE<br />

ARTERRA PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY*<br />

NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY<br />

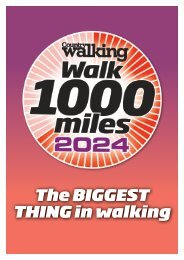

OWLS<br />

Owls have long been thought of as birds<br />

of ill omen – Shakespeare uses them<br />

as such in several of his plays. It’s not<br />

hard to understand why – their<br />

largely nocturnal habits and their<br />

eerie, far-carrying calls are to blame,<br />

with both Tawny and Barn Owls being<br />

thought of in this way. The latter’s<br />

all-white underside led to it being<br />

known as the ‘ghost owl’ at times, and<br />

it’s tempting to think that at least some<br />

ghost sightings over the years must have<br />

been down to the sight of one of these<br />

buoyant, silent hunters. Short-eared and<br />

Long-eared Owls seem to have slipped<br />

below the radar, while the Little Owl is, of<br />

course, a recent arrival, so has only just<br />

started to seep into British culture. But it<br />

may, ultimately, be responsible for that<br />

association with wisdom – it was the symbol<br />

of the Greek goddess Athena (Roman goddess<br />

Minerva), among whose gifts was wisdom.<br />

Interestingly, the fact that our folklore contains<br />

no trace of the Eagle Owl is held to be a reason why<br />

the UK’s small breeding population is considered to<br />

be derived from escaped falconers’ birds – such a<br />

fearsome über-predator would surely have surrounded<br />

itself with all sorts of associations, as in Norway for<br />

example, where it’s considered a bird of great ill omen (not<br />

least for its choice of prey).<br />

IT WAS THE SYMBOL OF THE GREEK<br />

GODDESS ATHENA, AMONG WHOSE<br />

GIFTS WAS WISDOM<br />

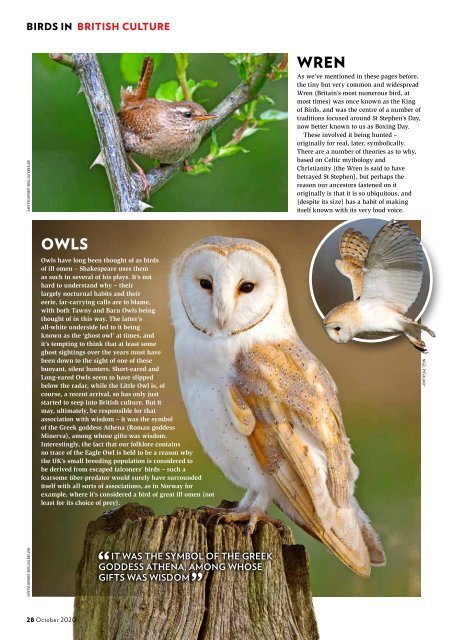

WREN<br />

As we’ve mentioned in these pages before,<br />

the tiny but very common and widespread<br />

Wren (Britain’s most numerous bird, at<br />

most times) was once known as the King<br />

of <strong>Bird</strong>s, and was the centre of a number of<br />

traditions focused around St Stephen’s Day,<br />

now better known to us as Boxing Day.<br />

These involved it being hunted –<br />

originally for real, later, symbolically.<br />

There are a number of theories as to why,<br />

based on Celtic mythology and<br />

Christianity (the Wren is said to have<br />

betrayed St Stephen), but perhaps the<br />

reason our ancestors fastened on it<br />

originally is that it is so ubiquitous, and<br />

(despite its size) has a habit of making<br />

itself known with its very loud voice.<br />

NIGEL PYE/ALAMY*<br />

NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY*<br />

NIGHTJAR<br />

It might seem strange, nowadays,<br />

given that even a lot of keen birders<br />

may never have seen a Nightjar, but<br />

it’s a species that has accumulated a<br />

lot of folk beliefs, and folk names to go<br />

with them. Many are variations on<br />

‘goatsucker’ (the meaning of the bird’s<br />

genus), and refer to the old belief<br />

(dating back to Ancient Greece) that<br />

they sucked the udders of goats. This<br />

probably arose because the birds<br />

would be regularly seen in close<br />

proximity to livestock, because of the<br />

insects attracted by the animals.<br />

Those beliefs, and the bird’s<br />

mysterious, elusive nature, made it a<br />

favourite of poets and writers through<br />

the centuries, from Wordsworth and<br />

his ‘dor-hawk’ to Dylan Thomas in his<br />

poem Fern Hill.<br />

Strangest of all, though, is the<br />

northern name ‘gabble-ratchet’, which<br />

links the Nightjar to the pagan legend<br />

of the Wild Hunt, presumably simply<br />

because of its nocturnal activities and<br />

churring song.<br />

IT MIGHT<br />

SEEM STRANGE,<br />

NOWADAYS, GIVEN<br />

THAT EVEN A LOT<br />

OF KEEN BIRDERS<br />

MAY NEVER HAVE<br />

SEEN A NIGHTJAR, BUT<br />

IT’S A SPECIES THAT HAS<br />

ACCUMULATED A LOT OF<br />

FOLK BELIEFS, AND FOLK<br />

NAMES TO GO WITH THEM<br />

GARY TACK/ALAMY*<br />

ROBIN<br />

No British bird is more closely connected<br />

to us than the Robin – polls have<br />

repeatedly named it our favourite, or<br />

national, bird, we send Christmas cards<br />

with its i<strong>mag</strong>e on, and gardeners treasure<br />

their habit of hopping around down by our<br />

feet as we dig. Until the Victorian era, it<br />

was generally known as the Redbreast, or<br />

Ruddock, due to its ruddy breast, in the<br />

same way as the Dunnock was named for<br />

its grey-brown (or dun) plu<strong>mag</strong>e. At some<br />

stage, though, the personal name Robin<br />

became attached (in the same way as the<br />

Jenny Wren), and the birds became linked<br />

to Christmas because Victorian postmen<br />

wore red coats, and when Christmas cards<br />

became fashionable, Robins were often<br />

depicted as postmen.<br />

But the Robin’s habit of singing even in<br />

midwinter must also have played a part in<br />

making its association with the season,<br />

and it seems that in Britain it’s always<br />

been considered unlucky to harm a Robin<br />

(see the nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock<br />

Robin?), in contrast to the situation on the<br />

continent, where they have been among<br />

the songbirds hunted as food.<br />

Their tameness here, perhaps, is a<br />

consequence of the affection that we have<br />

for them. Again, on the continent, they are<br />

often shy woodland birds, staying well<br />

away from gardens.<br />

MALCOLM SCHUYL/ALAMY*<br />

28 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 29