You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FREE EXPERT ID CARDS INSIDE<br />

Plus<br />

CUT OUT<br />

AND<br />

KEEP!<br />

ID essentials for beginners – wildfowl,<br />

woodpeckers, herons, tits, owls<br />

BRITAIN’S BEST-SELLING BIRD MAGAZINE<br />

OCTOBER <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong> £4.70<br />

Cultural<br />

ICONS<br />

l Why owls symbolise wisdom<br />

l How Robins became our<br />

favourite bird<br />

l Surprising truth about the<br />

Ravens at the Tower and more…<br />

ID<br />

CHALLENGE<br />

Expert help to<br />

separate riverside<br />

birds<br />

WHAT NEXT<br />

FOR THE RSPB?<br />

New boss Beccy Speight<br />

speaks out<br />

INCREDIBLE COSTA RICA<br />

Record-breaking birder Ruth Miller<br />

remembers a trip of a lifetime<br />

BEAUTIFUL BLACK GROUSE<br />

Explore this stunning bird’s extraordinary courtship habits

OCTOBER<br />

Contents<br />

14<br />

8<br />

NEWS & VIEWS<br />

16<br />

Weedon’s World<br />

Mike spent time photographing<br />

what he calls ‘elites’<br />

18<br />

NewsWire<br />

Can you help with funds to rebuild<br />

the Fair Isle <strong>Bird</strong> Observatory<br />

FEATURES<br />

<strong>20</strong><br />

26 36<br />

76<br />

19<br />

25<br />

Grumpy Old <strong>Bird</strong>er<br />

The scourge of wildlife crime is on<br />

Bo’s mind this month<br />

Hampshire 150<br />

How are team members faring with<br />

their <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong> photography challenge?<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

26 <strong>Bird</strong>s in British culture<br />

<strong>20</strong> ID essentials<br />

40 Beccy Speight interviewed<br />

44 Costa Rica<br />

36 Black Grouse<br />

47 ID Challenge<br />

IT’S NOT<br />

TOO LATE!<br />

BIRDWATCHING.<br />

CO.UK/MY<strong>20</strong>0<br />

<strong>20</strong><br />

24<br />

26<br />

32<br />

36<br />

40<br />

44<br />

70<br />

A guide to ID essentials<br />

A guide to our new series of ID<br />

cards, which will help you identify<br />

even more British birds!<br />

#My<strong>20</strong>0<strong>Bird</strong>Year sign up<br />

All the online help you need to boost<br />

your #My<strong>20</strong>0<strong>Bird</strong>Year list<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s in British culture<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s have long played a part in our<br />

folklore and mythology, as editor<br />

Matt Merritt discovers<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s in folk songs<br />

We highlight just a few of the many<br />

bird-related folk songs<br />

Black Grouse<br />

Do<strong>mini</strong>c Couzens on how life is<br />

tough for this upland bird<br />

RSPCA future<br />

We talk to the organisation’s<br />

new head, Beccy Speight<br />

Memories of Costa Rica<br />

How a heatwave in Wales got Ruth<br />

Miller thinking about exotic birding<br />

Wildlife photography<br />

A series of wonderful i<strong>mag</strong>es have<br />

been collected for a new publication<br />

40<br />

44<br />

8<br />

14<br />

47<br />

53<br />

IN THE FIELD<br />

Your <strong>Bird</strong>ing Month<br />

Find out why Great Northern Diver<br />

is our <strong>Bird</strong> of the Month! Plus, how<br />

Grey Wagtail got its name<br />

Beyond <strong>Bird</strong>watching<br />

Is <strong>October</strong> the end of summer or<br />

the start of winter, James Lowen<br />

wonders...<br />

ID Challenge<br />

Find out just how well you know<br />

river birds!<br />

Go <strong>Bird</strong>ing<br />

10 great destinations to<br />

head to for some brilliant birding<br />

SUBSCRIBE FOR<br />

£2.80<br />

PER MONTH*<br />

TURN THE PAGE<br />

*DIGITAL ONLY WHEN YOU PAY BY DIRECT DEBIT<br />

73<br />

76<br />

82<br />

86<br />

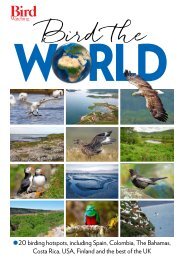

BIRD THE WORLD<br />

Highland birding<br />

How do you fancy a fabulous<br />

Highland winter birding trip in<br />

<strong>20</strong>21, with the team at Heatherlea?<br />

Belize<br />

Urban <strong>Bird</strong>er David Lindo heads to<br />

Central America for a trip of a<br />

lifetime and is not disappointed<br />

Texas<br />

A trip to the second largest US state<br />

will reward you a feast of great<br />

birds, as Barrie Cooper found to<br />

his delight<br />

Urban birding<br />

An ‘urban bird discovery’ was one<br />

of the many highlights on a trip to<br />

Mexico City for David Lindo<br />

BIRDING ON THE BRINK<br />

92 Bermuda Petrel<br />

How conservationists are<br />

helping this wonderful bird in its<br />

fight for survival<br />

67<br />

114<br />

114<br />

99<br />

102<br />

92<br />

94<br />

95<br />

Your Questions<br />

Our experts answer your birdingrelated<br />

questions<br />

Back Chat<br />

Young conservationist Kabir Kaul is<br />

in the Q&A hotseat!<br />

BIRD SIGHTINGS<br />

Rarity Round-Up<br />

The best rare birds seen in the<br />

UK during August<br />

UK <strong>Bird</strong> Sightings<br />

A comprehensive round-up of<br />

birds seen during August<br />

GEAR & REVIEWS<br />

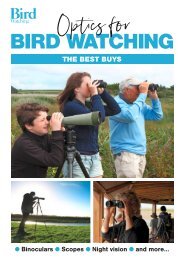

Gear<br />

Editor Matt tests the latest Hawke<br />

Endurance ED 15-45x60 scope<br />

WishList<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>ing goodies include camera<br />

lenses, feeders and shirts!<br />

Books<br />

Latest releases including<br />

A <strong>Bird</strong> A Day by Do<strong>mini</strong>c Couzens<br />

4 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong> birdwatching.co.uk 5

A t-a-glance<br />

Identification<br />

Trunk climbing woodland birds and tits<br />

Only Nuthatches go<br />

headfirst down tree trunks<br />

A guide to our new series of ID cards<br />

This month we have the second part of our series of cut-out-andkeep<br />

at-a-glance ID cards (which again you will find on the inside<br />

of the front cover of the <strong>mag</strong>azine). This time around we feature<br />

larger dabbling drakes, smaller diving ducks,<br />

widespread tit species, trunk-climbing birds, owls,<br />

pigeons, herons and other long-legged wading birds. Over the<br />

next four pages, we will look at a few tips to help you master the<br />

identification of these groups of British birds.<br />

Drake identification<br />

The ID cards cover 10 of our<br />

commoner species of duck,<br />

particularly drakes (male ducks):<br />

five are the larger dabbling ducks and five<br />

are smaller diving duck species. Here are<br />

some key points to consider.<br />

Head shape and colour<br />

The headshape in particular is as good a<br />

place to start as any, instantly narrowing<br />

down the possibilities. For instance, of the<br />

dabbling ducks, only drake Mallards and<br />

The Pintail is long-necked and<br />

long-tailed; the head is chocolate<br />

brown and the speculum is brownish<br />

Shovelers have blackish, glossy-green<br />

heads. And head colour will immediately<br />

tell a drake Scaup (blackish) from a drake<br />

Pochard (red).<br />

While at the head end, don’t forget to<br />

check out the bill shape and colour.<br />

Back colour etc in diving ducks<br />

In diving ducks, the colour of the back can<br />

be critical. For instance, Tufted Ducks have<br />

black backs, whereas the somewhat similar<br />

Scaup has a pale grey back. Similarly, in all<br />

The Goldeneye has an odd-shaped<br />

head with obvious white cheek patches,<br />

striped wings and a white breast<br />

PAUL A STERRY NATURE PHOTOGRAPHERS LTD/ALAMY TIM ZUROWSKI ALL CANADA PHOTOS /ALAMY*<br />

Red of head and pale grey on the<br />

flanks and back, the drake Pochard<br />

is very distinctive<br />

Predominantly grey-looking drake<br />

Gadwall has white ‘sugar lump’ speculums<br />

on the trailing edge of the wings<br />

male ducks, the colour of the breast is a<br />

very useful ID hint. Shovelers and Pintails,<br />

for instance, stand out as having white<br />

breasts; as do Goldeneye and Long-tailed<br />

Ducks among the diving ducks<br />

Speculum colour in dabblers<br />

Look for the square area of colour on<br />

the trailing edge of the wing of dabbling<br />

ducks. This ‘speculum’ can be critical in<br />

identification of birds in flight.<br />

DENNIS JACOBSEN/ALAMY<br />

BLICKWINKEL/M. WOIKE/ALAMY<br />

ARTERRA PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY<br />

ALAN WILLIAMS/ALAMY<br />

Card 6 is all about woodland<br />

birds, with one side dedicated to<br />

trunk-climbing species (the<br />

woodpeckers, Nuthatch and<br />

Treecreeper); and the other side the<br />

widespread species of tit (ie., all our<br />

true tit species, excluding the localised<br />

and very distinctive Crested Tit).<br />

Size<br />

Particularly with woodpeckers, size is a<br />

vital starting point. Our three resident<br />

woodpecker species are in three<br />

distinct size categories. In woodland<br />

conditions, looking into bright skies, a<br />

woodpecker-shaped silhouette is often<br />

all you get to see, as a bird flies off. So,<br />

a realisation that Green Woodpeckers<br />

are much larger than Great Spotted<br />

Woodpeckers, which in turn look huge<br />

compared with the scarce Lesser<br />

Spotted Woodpecker (or Nuthatch<br />

and Treecreeper) can be vital as a first<br />

(and perhaps final) step to confident<br />

identification of these birds.<br />

The Marsh Tit is very similar to the<br />

Willow Tit, and best distinguished by<br />

the tiny white mark on the bill<br />

The Treecreeper has a<br />

unique appearance among<br />

common British birds<br />

With our tit species, the thing to<br />

remember is that the Great Tit is almost<br />

sparrow-sized, the rest are much<br />

smaller, and the tiny Coal Tit is not<br />

much bigger than a Goldcrest!<br />

Head and face pattern<br />

Luckily, all the ‘trunk-climbing’ birds<br />

featured here have quite distinctive<br />

patterns, which can instantly identify<br />

them. Most of the tits, however, have<br />

black crowns, white cheeks and black<br />

bibs (the Blue Tit is the exception).<br />

Concentrate instead on the extent of the<br />

bib, and features like the white stripe on<br />

the back of the head of the Coal Tit.<br />

Tell-tale signs<br />

Just as the blue cap and white<br />

supercilium combination is unique to<br />

the Blue Tit, so the crimson on the lower<br />

belly and undertail coverts of the Great<br />

Spotted Woodpecker is a dead giveaway;<br />

no other similar birds you are likely to<br />

encounter will have this feature.<br />

A E BURRELL/ALAMY<br />

Colour<br />

Of the five tit species we are dealing with,<br />

the Blue and Great Tits are bright yellow<br />

beneath and have blue wings and tail<br />

and a green back. The extremely similar<br />

(to each other) Marsh and Willow Tit are<br />

fundamentally brown birds. And the Coal<br />

Tit is a grey-and-buff bird, on its own.<br />

Similarly, basic colour is a good next stage<br />

in ID (after size) with the woodpeckers<br />

and other climbing species. For example,<br />

only the Green Woodpecker is green, only<br />

the Nuthatch blue-grey and buff.<br />

Feeding area<br />

It can be useful to know where in the<br />

woodland (or indeed out of the woodland)<br />

these birds feed. Green Woodpeckers do<br />

nearly all their feeding on ground<br />

(hoovering up ants), while Lesser Spotted<br />

Woodpeckers favour the tiny uppermost<br />

branches. Nuthatches can be found all<br />

over trees, and will walk headfirst down<br />

them, unlike Treecreepers, which like to<br />

spiral up trunks.<br />

WillowTits have subtly larger heads<br />

than Marsh Tits and more ‘tonally<br />

constant’ flanks and backs<br />

COLIN VARNDELL/ALAMY<br />

BRIAN SCOTT/ALAMY<br />

<strong>20</strong> <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 21

Owls and pigeons and doves<br />

Herons, egrets and long-legged wading birds<br />

The Great White Egret is very large, with a<br />

distinctive kink in the neck and usually a<br />

long ,orange-yellow bill<br />

The next card deals with two quite<br />

different medium-sized nonpasserine<br />

bird groups: owls and<br />

the pigeons and doves.<br />

When do they fly?<br />

Although owls are famous for being<br />

nocturnal, it is useful to know that some<br />

will readily hunt during the day, while<br />

others are rarely seen while the sun is up.<br />

In short, the Tawny Owl and Long-eared<br />

Owl are pretty rigorously nocturnal in<br />

their activities, while the other three<br />

species can be seen out in full sunlight,<br />

particularly Barn Owls, when there are<br />

young in the nest to feed.<br />

Pigeons vs doves<br />

Although these terms are pretty<br />

interchangeable, the word pigeon is used<br />

more often for the larger species,<br />

particularly those of the genus Columba<br />

(Woodpigeon, Stock Dove and Rock Dove/<br />

Feral Pigeon); while those smaller birds in<br />

the genus Streptopelia (Collared Dove and<br />

Turtle Dove) are always called doves.<br />

Eye colour<br />

Somewhat surprisingly for birds which are<br />

not often seen up close and personal, eye<br />

colour can be useful in identifying owls.<br />

Tawny and Barn Owls have dark eyes, but<br />

the real crux comes with the similar<br />

Stock Doves are subtle beauties of birds,<br />

with short wing-bars and a glorious splash<br />

of iridescence on the neck<br />

Short-eared and Long-eared Owls. If all<br />

you can see of a roosting ‘eared’ owl<br />

within a bush, is part of its face, then the<br />

eye colour can help identify it: orange for<br />

Long-eared and yellow for Short-eared.<br />

Wing and tail pattern and rump<br />

Of the doves, only the Woodpigeon has<br />

big white wing flashes, only the Rock<br />

Dove/Feral Pigeon has a white rump<br />

and long dark wing-bars, and only the<br />

Turtle Dove has a dark tail with a white<br />

terminal band.<br />

Apart from the ‘ears’, Long-eared Owls<br />

have orange eyes and often have<br />

orange facial discs<br />

The Turtle Dove has a<br />

unique Zebra-striped<br />

neck patch<br />

DAVID CHAPMAN/ALAMY* DAVID CHAPMAN/ALAMY NEIL BOWMAN/ALAMY<br />

Our final card features birds<br />

colloquially known as long-legged<br />

wading birds (not to be confused<br />

with the true ‘waders’). One side<br />

concentrates on the herons and egrets. The<br />

other has one heron, the Bittern, and a<br />

hotchpotch of lanky, long-necked birds.<br />

Start with colour<br />

Unlike many bird groups, colour is a crucial<br />

first ID step with these species. Great White<br />

and Little Egrets are wholly white in<br />

plu<strong>mag</strong>e, and Cattle Egret and Spoonbill are<br />

predominantly white birds. White Storks<br />

are also white, but have big black areas on<br />

the wings, which are immediately obvious.<br />

So, if it is white, you can narrow the bird<br />

down, dramatically, to one of a few species.<br />

Size matters<br />

These birds vary from the huge Crane and<br />

White Stork through the larger herons and<br />

Great White Egret, to relatively small birds,<br />

like Little and Cattle Egrets and Glossy Ibis.<br />

Compare with other nearby birds.<br />

Flight style<br />

All the herons nearly always fly with the<br />

neck folded up, whereas all the other<br />

species have the neck fully extended in<br />

flight. The Bittern, a heron, also folds the<br />

neck, but it has so much feathering it just<br />

looks thick-necked.<br />

BW<br />

WERNER LAYER MAURITIUS IMAGES GMBH/ALAMYY*<br />

Little Egrets are slim,<br />

dark-billed, with black legs<br />

yet yellow footed<br />

White Storks are unmistakable:<br />

huge, white and black, with long<br />

red bill and red legs<br />

MIKE LANE/ALAMY<br />

Cattle Egrets are chunky<br />

with a short, orange bill and<br />

some orange in the plu<strong>mag</strong>e<br />

NICK UPTON/ALAMY<br />

STEPHAN MORRIS PHOTOGRAPHY/ALAMY*<br />

22 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 23

GREAT GREY BIRDS IN BRITISH CULTURE<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s in<br />

British culture<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s have long played a part in our folklore and<br />

mythology, as Matt Merritt discovers…<br />

ADAM GASSON/ALAMY<br />

ROCK DOVE/<br />

FERAL PIGEON<br />

The first species might not immediately<br />

spring to mind, partly because it’s so<br />

ubiquitous. Genuine Rock Doves<br />

themselves are not easy to find these days,<br />

except on the wildest and loneliest coasts<br />

of Scotland, Ireland and Wales, but the<br />

Feral Pigeon, a species descended from<br />

domesticated Rock Doves, is everywhere.<br />

While we might not immediately make<br />

the traditional connection between it and<br />

fertility – something that made it one of<br />

the main bird symbols of the ancient<br />

world – we still feed them and live cheek<br />

by jowl with them in our towns and cities,<br />

and of course pigeon fancying is still a<br />

pastime with a lot of adherents. So, forget<br />

about calling them ‘sky rats’, and give<br />

them the respect they deserve.<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s tend to feature heavily in<br />

the folklore, mythology and<br />

cultures of most parts of the<br />

world – they’re highly visible,<br />

they’re pretty much<br />

everywhere, and their power of flight,<br />

with all the metaphorical possibilities that<br />

go with that, is something we envy.<br />

REALIMAGE/ALAMY<br />

Herring Gull<br />

Britain is no exception. To some extent,<br />

the phenomenon is exaggerated here,<br />

because we have relatively little in the way<br />

of mammal life, so birds have always been<br />

the most immediate and obvious<br />

candidates to get used in symbolism.<br />

You could write a very big book about<br />

all the ways in which birds are embedded<br />

in our culture (in fact, likes of Mark<br />

Cocker and Richard Mabey already have,<br />

in their tome <strong>Bird</strong>s Britannica).<br />

Folk song is just one of aspect of the<br />

cultural impact of birds (see our feature on<br />

page 32), but read on to discover some of<br />

the bird species that have left a deep mark<br />

on our culture.<br />

RAVEN<br />

The largest of our crows has<br />

left a huge impression on<br />

us for a number of reasons,<br />

but the main one might be<br />

that we once formed a<br />

significant part of their<br />

diet! Right up to the end of<br />

the medieval period, frequent<br />

warfare and battles meant there<br />

was no shortage of human corpses<br />

for these carrion birds to feed on, as<br />

old ballads such as Twa Corbies attest.<br />

Further back it’s thought that some Stone<br />

Age peoples deliberately left dead bodies out<br />

for Ravens to pick clean, and consequently,<br />

they became a symbol of death, foreboding<br />

and evil. But there’s another key factor at<br />

work: Ravens are very intelligent. For that<br />

reason, perhaps, the Vikings believed that<br />

Odin, their main god, had two Ravens, Huginn<br />

and Muninn, who reported back to him on<br />

everything they saw each day. It’s possible that<br />

the Anglo-Saxons believed similar of their<br />

Odin equivalent, Woden, too. So we venerate<br />

as well as fear these crows – the beliefs<br />

attached to the Ravens at the Tower of<br />

London (it will fall down if<br />

they leave) are an<br />

example of that.<br />

Ravens<br />

at the<br />

Tower of<br />

London<br />

HUGH THRELFALL/ALAMY*<br />

FLPA/ ALAMY*<br />

26 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 27

BIRDS IN BRITISH CULTURE<br />

ARTERRA PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY*<br />

NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY<br />

OWLS<br />

Owls have long been thought of as birds<br />

of ill omen – Shakespeare uses them<br />

as such in several of his plays. It’s not<br />

hard to understand why – their<br />

largely nocturnal habits and their<br />

eerie, far-carrying calls are to blame,<br />

with both Tawny and Barn Owls being<br />

thought of in this way. The latter’s<br />

all-white underside led to it being<br />

known as the ‘ghost owl’ at times, and<br />

it’s tempting to think that at least some<br />

ghost sightings over the years must have<br />

been down to the sight of one of these<br />

buoyant, silent hunters. Short-eared and<br />

Long-eared Owls seem to have slipped<br />

below the radar, while the Little Owl is, of<br />

course, a recent arrival, so has only just<br />

started to seep into British culture. But it<br />

may, ultimately, be responsible for that<br />

association with wisdom – it was the symbol<br />

of the Greek goddess Athena (Roman goddess<br />

Minerva), among whose gifts was wisdom.<br />

Interestingly, the fact that our folklore contains<br />

no trace of the Eagle Owl is held to be a reason why<br />

the UK’s small breeding population is considered to<br />

be derived from escaped falconers’ birds – such a<br />

fearsome über-predator would surely have surrounded<br />

itself with all sorts of associations, as in Norway for<br />

example, where it’s considered a bird of great ill omen (not<br />

least for its choice of prey).<br />

IT WAS THE SYMBOL OF THE GREEK<br />

GODDESS ATHENA, AMONG WHOSE<br />

GIFTS WAS WISDOM<br />

WREN<br />

As we’ve mentioned in these pages before,<br />

the tiny but very common and widespread<br />

Wren (Britain’s most numerous bird, at<br />

most times) was once known as the King<br />

of <strong>Bird</strong>s, and was the centre of a number of<br />

traditions focused around St Stephen’s Day,<br />

now better known to us as Boxing Day.<br />

These involved it being hunted –<br />

originally for real, later, symbolically.<br />

There are a number of theories as to why,<br />

based on Celtic mythology and<br />

Christianity (the Wren is said to have<br />

betrayed St Stephen), but perhaps the<br />

reason our ancestors fastened on it<br />

originally is that it is so ubiquitous, and<br />

(despite its size) has a habit of making<br />

itself known with its very loud voice.<br />

NIGEL PYE/ALAMY*<br />

NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY*<br />

NIGHTJAR<br />

It might seem strange, nowadays,<br />

given that even a lot of keen birders<br />

may never have seen a Nightjar, but<br />

it’s a species that has accumulated a<br />

lot of folk beliefs, and folk names to go<br />

with them. Many are variations on<br />

‘goatsucker’ (the meaning of the bird’s<br />

genus), and refer to the old belief<br />

(dating back to Ancient Greece) that<br />

they sucked the udders of goats. This<br />

probably arose because the birds<br />

would be regularly seen in close<br />

proximity to livestock, because of the<br />

insects attracted by the animals.<br />

Those beliefs, and the bird’s<br />

mysterious, elusive nature, made it a<br />

favourite of poets and writers through<br />

the centuries, from Wordsworth and<br />

his ‘dor-hawk’ to Dylan Thomas in his<br />

poem Fern Hill.<br />

Strangest of all, though, is the<br />

northern name ‘gabble-ratchet’, which<br />

links the Nightjar to the pagan legend<br />

of the Wild Hunt, presumably simply<br />

because of its nocturnal activities and<br />

churring song.<br />

IT MIGHT<br />

SEEM STRANGE,<br />

NOWADAYS, GIVEN<br />

THAT EVEN A LOT<br />

OF KEEN BIRDERS<br />

MAY NEVER HAVE<br />

SEEN A NIGHTJAR, BUT<br />

IT’S A SPECIES THAT HAS<br />

ACCUMULATED A LOT OF<br />

FOLK BELIEFS, AND FOLK<br />

NAMES TO GO WITH THEM<br />

GARY TACK/ALAMY*<br />

ROBIN<br />

No British bird is more closely connected<br />

to us than the Robin – polls have<br />

repeatedly named it our favourite, or<br />

national, bird, we send Christmas cards<br />

with its i<strong>mag</strong>e on, and gardeners treasure<br />

their habit of hopping around down by our<br />

feet as we dig. Until the Victorian era, it<br />

was generally known as the Redbreast, or<br />

Ruddock, due to its ruddy breast, in the<br />

same way as the Dunnock was named for<br />

its grey-brown (or dun) plu<strong>mag</strong>e. At some<br />

stage, though, the personal name Robin<br />

became attached (in the same way as the<br />

Jenny Wren), and the birds became linked<br />

to Christmas because Victorian postmen<br />

wore red coats, and when Christmas cards<br />

became fashionable, Robins were often<br />

depicted as postmen.<br />

But the Robin’s habit of singing even in<br />

midwinter must also have played a part in<br />

making its association with the season,<br />

and it seems that in Britain it’s always<br />

been considered unlucky to harm a Robin<br />

(see the nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock<br />

Robin?), in contrast to the situation on the<br />

continent, where they have been among<br />

the songbirds hunted as food.<br />

Their tameness here, perhaps, is a<br />

consequence of the affection that we have<br />

for them. Again, on the continent, they are<br />

often shy woodland birds, staying well<br />

away from gardens.<br />

MALCOLM SCHUYL/ALAMY*<br />

28 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 29

BIRDS IN BRITISH CULTURE<br />

FLPA/ALAMY*<br />

THEY BECAME A<br />

POWERFUL SYMBOL OF HOME,<br />

AND NORMALITY,<br />

FOR SOLDIERS ENDURING<br />

UNIMAGINABLE<br />

MISERY<br />

SKY LARK<br />

Sky Larks don’t necessarily crop up in our folklore<br />

a great deal, but no British bird has been so beloved<br />

of poets over the centuries, except perhaps the<br />

Nightingale. As a symbol of spring, it is without<br />

equal. The most famous example is probably<br />

George Meredith’s poem The Lark Ascending, which<br />

inspired Ralph Vaughan Williams’ orchestral piece of<br />

the same name, often voted among the nation’s<br />

favourite pieces of classical music.<br />

And Sky Larks took on a new significance in the<br />

horror of the trenches of World War I, with more than<br />

one writer commenting on them continuing to sing<br />

even amid the barrages and machine-gun fire – they<br />

then became a powerful symbol of home, and<br />

normality, for soldiers enduring uni<strong>mag</strong>inable misery.<br />

Two of the best of such poems are Isaac Rosenberg’s<br />

Returning, We Hear The Larks, and John McRae’s<br />

In Flanders Fields.<br />

SEABIRDS<br />

For an island in which it’s impossible to get more than<br />

about 80 miles from the sea, seabirds don’t play as central<br />

a role in our culture and folklore as you might expect,<br />

notwithstanding our affection for Puffins. But seabirds<br />

can claim to be among the first birds to be mentioned in<br />

English literature, with Gannets, gulls and White-tailed<br />

Eagles (‘ernes’) all cropping up in the Anglo-Saxon poem<br />

The Seafarer, written sometime before the 10th Century. It<br />

also mentions ‘huilpan’, meaning Curlews or Whimbrels,<br />

with the word living on in some dialect names for the<br />

species, such as ‘whaup’. BW<br />

FOR AN ISLAND IN WHICH<br />

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO GET<br />

MORE THAN ABOUT 80 MILES<br />

FROM THE SEA, SEABIRDS<br />

DON’T PLAY AS CENTRAL<br />

A ROLE IN OUR CULTURE<br />

AND FOLKLORE AS YOU<br />

MIGHT EXPECT<br />

Puffin<br />

ARTERRA PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY*<br />

STEVE LINDRIDGE/ALAMY*<br />

White-tailed Eagle<br />

30 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong>

<strong>Bird</strong>ing from home?<br />

Download every issue to your phone or tablet instead!<br />

NEVER<br />

MISS<br />

AN<br />

ISSUE!<br />

Here at <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Watching</strong> we fully appreciate what a difficult time we are living in. While we can’t<br />

wave a <strong>mag</strong>ic wand and return life to normal, we can keep you entertained with your favourite<br />

birdwatching <strong>mag</strong>azine. For a single digital issue simply download the <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Watching</strong> Magazine<br />

app from the Apple App Store or Google Play or from the Amazon Newsstand.<br />

If you enjoy a single digital issue you can purchase a digital subscription from:<br />

great<strong>mag</strong>azines.co.uk/bw

Yellow-throated Toucan<br />

RUTH<br />

MILLER<br />

Montezuma Oropendola<br />

OBSERVATIONS<br />

Blue-grey Tanager<br />

Selva Verde<br />

Sunbittern<br />

The recent heatwave prompted Ruth to remember the<br />

time she experienced the humidity of birding in Costa Rica<br />

It didn’t feel like being in the UK<br />

during the heatwave that we<br />

experienced in August. The<br />

incredible heat, humidity and<br />

monsoon-like thunderstorms were<br />

more like Costa Rica than Costa de<br />

North Wales. The still air was thick<br />

with heat, making it hard to concentrate<br />

on the computer screen, and easy to drift<br />

off into a daydream.<br />

In an instant, I was back in one of my<br />

favourite destinations in Costa Rica, the<br />

wonderful lodge at Selva Verde in the<br />

Sarapiqui region. It’s our first destination<br />

on a birdwatching trip to the country and<br />

a superb introduction to Costa Rica birding.<br />

Selva Verde lodge is set within its own<br />

substantial grounds on the banks of the<br />

Sarapiqui River. The buildings are<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY: RUTH MILLER<br />

Red-legged Honeycreeper<br />

surrounded by lush vegetation: the<br />

towering trees, massive-leaved bushes,<br />

looming bromeliads and swinging lianas of<br />

a tropical rainforest. High-level trails lead<br />

you through the forest to your cabin, so it’s<br />

easy to get distracted on your way to your<br />

room by a striking Orange-billed Sparrow<br />

or a marvellous Montezuma Oropendola,<br />

a feast for the ears as well as the eyes.<br />

The dining area is designed with wildlife<br />

in mind too. Inside the spacious dining<br />

room there are plenty of comfortable tables<br />

and chairs where wooden fans waft the air<br />

gently, to create a cooling breeze while you<br />

eat. But why sit there when outside is a<br />

fantastic veranda overlooking a feeding<br />

station? And what a feeding station it is!<br />

Forget your peanut feeder with some<br />

sunflower hearts on the side. This is a<br />

Orange -billed Sparrow<br />

NICARAGUA<br />

SAN JOSÉ<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

PANAMA<br />

full-scale construction of aged wooden logs,<br />

vines and creepers all blending perfectly<br />

with the natural surroundings, making it<br />

ideal for photography. And, being right<br />

beside the dining room, it is always kept<br />

well stocked with fruit – mainly papaya<br />

and bananas – throughout the day.<br />

The whole set-up is very appealing for<br />

Summer Tanager<br />

SELVA VERDE LODGE,<br />

SARAPIQUI<br />

avian diners, and the birds seem to<br />

know the instant their dining table is<br />

refreshed. The confident tanagers are<br />

usually first: in swoops a tomato-red<br />

male Summer Tanager, or the cooler sky<br />

tones of a Blue-grey Tanager.<br />

Confident swagger<br />

It takes longer to say Red-throated Ant-<br />

Tanager than it does for the bird to sneak in,<br />

grab some fruit and dash off to the security<br />

of the bushes again, while bandit-masked<br />

Red-legged Honeycreepers, a symphony in<br />

azure-blue and black with startling red legs,<br />

swagger confidently across the feeding<br />

station to commandeer the ripest fruit.<br />

The larger birds are curiously often more<br />

cautious when it comes to feeding in full<br />

view of their admiring public. Yellowthroated<br />

(once called Chestnut-mandibled)<br />

Toucans are noisy characters when<br />

communicating through the forest to one<br />

another, but their approach to the feeding<br />

station is taken quietly, in stages.<br />

Slowly, slowly they approach, pausing<br />

first on one branch to survey the situation,<br />

before dropping down to perch on the next.<br />

They swivel their heads slowly in a full arc<br />

to check in all directions; holding their head<br />

like an angle-poise lamp to check up, down,<br />

left and right past their bizarre two-tone<br />

sheath-shaped bill. At last they decide it’s<br />

safe to hop down onto a vine beside the<br />

bunch of bananas. That bonkers bill may<br />

be large to manoeuvre, but they delicately<br />

break off a piece of banana using just the<br />

very tip and then throw their head<br />

backwards to toss the mouthful right to<br />

the back of the throat.<br />

One gulp and it’s gone; a banana doesn’t<br />

last long when there’s a hungry Yellowthroated<br />

Toucan in the area.<br />

Word gets out, and mammals also<br />

approach to enjoy the banana bonanza.<br />

Nimble-pawed and whiffling its flexible<br />

nose at the smell of ripe fruit, a Coatimundi,<br />

or Coati, shimmies fearlessly onto the<br />

feeding station and tucks in with gusto,<br />

scattering all the birds and refusing to<br />

budge from the table, until it has<br />

demolished the very last of the fruit.<br />

It’s distracting with so much to watch<br />

while you dine, so luckily lunch breaks<br />

are usually pretty long at Selva Verde. But<br />

a visit by one particular bird had all the<br />

human diners dropping their cutlery and<br />

rushing for a look.<br />

Ivan, the lodge’s expert resident guide,<br />

burst round the corner in excitement. We<br />

tiptoed silently to where he peered over the<br />

balcony and followed the direction of his<br />

pointing finger. Below us was a small<br />

ornamental freshwater pool, surrounded by<br />

stones and shaded by leafy vegetation.<br />

Pottering around in this tiny pool like a<br />

flamingo in a bathtub, was an incredible<br />

bird: a Sunbittern! This extraordinary,<br />

heron-like bird, normally so shy and<br />

Coati on fruit<br />

skulking, was so absorbed in its hunt for<br />

minuscule fish in the pond that it was<br />

oblivious to its stunned audience.<br />

Wonderful barring across its back blended<br />

with the dappled sunlight and bold white<br />

headstripes led the eye to its dagger-like bill<br />

with which it stabbed the shady depths for<br />

fry. Suddenly, it realised it was being<br />

watched and alarmed at being caught in the<br />

act of fishing, it opened its wings and with<br />

a bustle and flurry flew to the cover of the<br />

riverbank. Oh, be still my beating heart at<br />

that perfect view of a Sunbittern.<br />

I was brought down to earth by the sound<br />

of Herring Gulls over Llandudno in North<br />

Wales. The temperatures may have been the<br />

same as Costa Rica but there ended the<br />

similarity. But a girl can daydream, and<br />

while we yearn for a return to ‘normal’,<br />

I can hope for a return visit to Costa Rica,<br />

Selva Verde and a very special bird indeed.<br />

Ruth Miller is one half of The Biggest Twitch<br />

team, and along with partner Alan Davies, set the<br />

then world record for most bird species seen in a<br />

year – 4,341, in <strong>20</strong>08, an experience they wrote<br />

about in their book, The Biggest Twitch. Indeed,<br />

Ruth is still the female world record-holder! As well<br />

as her work as a tour leader, she is the author of the<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s, Boots and Butties books, on walking, birding<br />

and tea-drinking in North Wales, and previously<br />

worked as the RSPB’s head of trading. She lives in<br />

North Wales. birdwatchingtrips.co.uk<br />

BW<br />

44 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

birdwatching.co.uk 45

PART 2 BERMUDA PETREL<br />

BIRDS ON THE BRINK<br />

Every issue over the next year, the team behind <strong>Bird</strong> Photographer of the Year<br />

will look at conservation issues surrounding different species from the UK and<br />

beyond, using beautiful i<strong>mag</strong>es to inspire. This month it is the Bermuda Petrel<br />

NEXT<br />

MONTH:<br />

Honey<br />

Buzzard<br />

WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY: PAUL STERRY<br />

Bermuda Petrel<br />

Pterodroma cahow<br />

l World Population: 125<br />

pairs (source: Bermuda<br />

Audubon Society)<br />

l IUCN Red List Category:<br />

Globally Threatened,<br />

Vulnerable<br />

The fate of the Bermuda Petrel is<br />

quite literally in our hands; and<br />

without positive human intervention,<br />

by now it would almost<br />

certainly have slipped over<br />

the brink into extinction.<br />

A Bermuda Petrel or Cahow<br />

at sea off Bermuda. Like<br />

other Pterodroma petrels,<br />

they are consummate<br />

aeronauts, able to ride the<br />

ocean winds with ease<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s on the Brink is a conservation grant-awarding<br />

charity (Charity No: 1188009) that owns the<br />

competition <strong>Bird</strong> Photographer of the Year. Grants<br />

are awarded to projects that support bird<br />

conservation, typically offering between £<strong>20</strong>0 and<br />

£1,000 to small groups or individuals carrying out<br />

grassroots conservation work that has measurable<br />

impact. It was borne of a passion for wildlife and in<br />

particular birds, and is a response to the seemingly<br />

unstoppable process of human environmental<br />

exploitation and biodiversity’s steady progression<br />

towards extinction. At its heart there is a<br />

recognition that all is not yet lost and <strong>Bird</strong>s on the<br />

Brink aims to inspire people to care using striking<br />

i<strong>mag</strong>ery - to capture the i<strong>mag</strong>ination and thereby<br />

nurture interest and compassion. <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Watching</strong><br />

<strong>mag</strong>azine is proud to support conservation and<br />

money generated by these articles will contribute<br />

to the funds of <strong>Bird</strong>s on the Brink.<br />

For more information, visit the website at<br />

birdsonthebrink.co.uk<br />

90 <strong>October</strong> <strong>20</strong><strong>20</strong><br />

The Cahow (or Bermuda<br />

Petrel) is Bermuda’s national<br />

bird, and over the years this<br />

exquisite grey Pterodroma<br />

has acquired almost mythical<br />

status, thanks to its remarkable story. It<br />

is the stuff of birding legend. Thought to<br />

be extinct for over three centuries, it was<br />

rediscovered and then brought back from<br />

the brink by the efforts of a few dedicated<br />

people; its recovery is one of<br />

conservation’s most heart-warming<br />

success stories.<br />

Sub-fossil records indicate that the<br />

Cahow (to give it the local name) was an<br />

abundant breeder on Bermuda prior to<br />

human settlement. Its demise began with<br />

the arrival of Man, and from the 1500s<br />

onwards, exploitation for food, habitat<br />

destruction, and predation by rats, cats<br />

and pigs helped eradicate it from the<br />

main islands. There were no records after<br />

16<strong>20</strong> and the bird was assumed extinct.<br />

After a couple of false starts, during an<br />

expedition in 1951 (in which the<br />

legendary David Wingate participated)<br />

the species’ survival was confirmed – on<br />

just five tiny, limestone islets in Castle<br />

Harbour, in the north of Bermuda.<br />

The entire world population that year<br />

was estimated to be just 17 pairs, with<br />

just eight chicks being produced.<br />

The islets on which the Cahow survived<br />

were vulnerable to rising sea levels and<br />

hurricane da<strong>mag</strong>e. Plus, the birds also had<br />

to contend with White-tailed Tropicbirds<br />

entering their nest burrows and killing the<br />

chicks. In response, David Wingate<br />

constructed igloo-style entrance baffles<br />

that prevented the tropicbirds gaining<br />

access; and his ecological restoration of<br />

nearby Nonsuch Island Nature Reserve<br />

(as a site for natural recolonisation)<br />

underpinned the next chapter in the story<br />

of the Cahow’s recovery.<br />

But continued erosion of the islets meant<br />

that drastic measures had to be taken. So,<br />

in <strong>20</strong>01 the Cahow’s current guardian<br />

angel, Jeremy Madeiros, began<br />

translocating chicks just prior to fledging,<br />

to artificial burrows on predator-free<br />

Nonsuch Island. The idea was that the<br />

chicks would imprint on the burrows from<br />

which they fledged. The project has been a<br />

resounding success and in the <strong>20</strong>18 nesting<br />

season 125 pairs were identified.<br />

Through the Bermuda Audubon Society<br />

(a non-profit charity) <strong>Bird</strong> Photographer of<br />

the Year and <strong>Bird</strong>s of the Brink are proud<br />

to help raise funds for, and awareness of,<br />

the Cahow nest-site programme, and so far<br />

we have donated £500 to help their efforts.<br />

SUB-FOSSIL RECORDS INDICATE THAT THE CAHOW<br />

WAS AN ABUNDANT BREEDER ON BERMUDA PRIOR TO<br />

HEUMAN SETTLEMENT<br />

The Bermuda Petrel’s current guardian angel,<br />

Jeremy Madeiros, checking on one of the<br />

nest-prospecting birds<br />

November presents a rare opportunity to see Bermuda Petrels in daylight. As dusk falls,<br />

nest-prospecting birds approach land to stake a claim on a burrow (mostly artificial these days)<br />

and courting pairs are sometimes observed at sea. After that, the petrels head back to sea for a<br />

few weeks before returning to lay eggs<br />

Free from ground predators and most non-native species, tiny Nonsuch Island, just a few hundred metres from the<br />

main island, is the Bermuda Petrel’s new sanctuary<br />

As the sun sets Bermuda Petrels move ever-closer to land, but they don’t<br />

return to Nonsuch Island until it is completely dark<br />

birdwatching.co.uk 91

NEXT ISSUE<br />

DOWN IN<br />

HISTORY<br />

Why there’s much more to<br />

Eiders than meets the eye<br />

November issue on sale<br />

22 OCTOBER<br />

And all the regulars<br />

10 great new Go <strong>Bird</strong>ing sites<br />

UK <strong>Bird</strong> Sightings<br />

News, reviews and much more<br />

PRE-ORDER<br />

AND GET<br />

FREE UK P&P<br />

FROM<br />

19 0CTOBER ON<br />

great<strong>mag</strong>azines.<br />

co.uk/bird<br />

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE TO START...<br />

BIRDWATCHING.CO.UK/MY<strong>20</strong>0<br />

GLENN WELCH/ALAMY<br />

CONTACT US<br />

<strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Watching</strong>, Media House, Lynch Wood, Peterborough<br />

PE2 6EA<br />

Email: birdwatching@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

Phone 01733 468000<br />

Editor Matt Merritt<br />

matthew.merritt@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

Assistant Editor Mike Weedon<br />

mike.weedon@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

Production Editor Mike Roberts<br />

mike.roberts@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

Art Editor Mark Cureton<br />

mark.cureton@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

Editorial Assistant Nicki Manning<br />

nicki.manning@bauermedia.co.uk<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

Debbie Etheridge 01733 366407<br />

Jacquie Pasqualone 01733 366371<br />

Haania Anwar 01733 466368<br />

MARKETING<br />

Phone 01733 468129<br />

Product Manager Naivette Bluff<br />

Direct Marketing Manager Julie Spires<br />

PRODUCTION<br />

Phone 01733 468341<br />

Print Production Controller Colin Robinson<br />

Newstrade Marketing Manager:<br />

Samantha Thompson<br />

Printed by Walstead Peterborough<br />

Distributed by Frontline<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS AND BACK ISSUES<br />

To ensure you don’t miss an issue visit<br />

www.great<strong>mag</strong>azines.co.uk<br />

To contact us about subscription orders,<br />

renewals, missing issues or any other<br />

subscription queries, please email<br />

bauer@subscription.co.uk or call our UK number on<br />

01858 438884 or overseas call<br />

+44 1858 438884.<br />

To manage your account online<br />

visit www.great<strong>mag</strong>azines.co.uk/solo<br />

To order back issues please call our UK number<br />

on 01858 438884, for overseas call<br />

+44 1858 438884.<br />

H BAUER PUBLISHING<br />

Managing Director Sam Gallimore<br />

Editorial Director June Smith-Sheppard<br />

Digital Managing Director Charlie Calton-Watson<br />

Chief Financial Officer<br />

Bauer Magazine Media Lisa Hayden<br />

CEO, Bauer Publishing UK Chris Duncan<br />

President, Bauer Global Publishing<br />

Rob Munro-Hall<br />

COMPLAINTS: H Bauer Publishing<br />

Limited is a member of the<br />

Independent Press Standards<br />

Organisation (ipso.co.uk) and endeavours to respond to and resolve<br />

your concerns quickly. Our Editorial Complaints Policy (including full<br />

details of how to contact us about editorial complaints and IPSO’s<br />

contact details) can be found at bauermediacomplaints.co.uk. Our e<br />

mail address for editorial complaints covered by the Editorial<br />

Complaints Policy is complaints@bauermedia.co.uk.<br />

<strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Watching</strong> <strong>mag</strong>azine is published 13 times a year by H Bauer<br />

Publishing Ltd, registered in England and Wales with company<br />

number LP003328, registered address Academic House, 24-28 Oval<br />

Road, London, NW1 7DT. VAT no 918 5617 01<br />

H Bauer Publishing and Bauer Consumer Media Ltd are authorised<br />

and regulated by the FCA (Ref No. 845898) and (Ref No. 710067)<br />

No part of the <strong>mag</strong>azine may be reproduced in any form in whole or<br />

in part, without the prior permission of Bauer. All material published<br />

remains the copyright of Bauer and we reserve the right to copy or<br />

edit, any material submitted to the <strong>mag</strong>azine without further consent.<br />

The submission of material (manuscripts or i<strong>mag</strong>es etc) to H Bauer<br />

whether unsolicited or requested, is taken as permission to<br />

publish that material in the <strong>mag</strong>azine, on the associated website, any<br />

apps or social media pages affiliated to the <strong>mag</strong>azine, and any<br />

editions of the <strong>mag</strong>azine published by our licensees elsewhere in the<br />

world. By submitting any material to us you are confirming that the<br />

material is your own original work or that you have permission from<br />

the copyright owner to use the material and to and authorise Bauer to<br />

use it as described in this paragraph. You also promise that you<br />

have permission from anyone featured or referred to in the submitted<br />

material to it being used by Bauer. If Bauer receives a claim from a<br />

copyright owner or a person featured in any material you have sent us,<br />

we will inform that person that you have granted us permission to use<br />

the relevant material and you will be responsible for paying any<br />

amounts due to the copyright owner or featured person and / or for<br />

reimbursing Bauer for any losses it has suffered as a result. Please<br />

note, we accept no responsibility for unsolicited material which is lost<br />

or da<strong>mag</strong>ed in the post and we do not promise that we will be able to<br />

return any material to you. Finally, whilst we try to ensure accuracy of<br />

your material when we publish it, we cannot promise to do so.<br />

We do not accept any responsibility for any loss or da<strong>mag</strong>e, however<br />

caused, resulting from use of the material as described in this<br />

paragraph.<br />

Sydnication department: syndication@bauermedia.co.uk