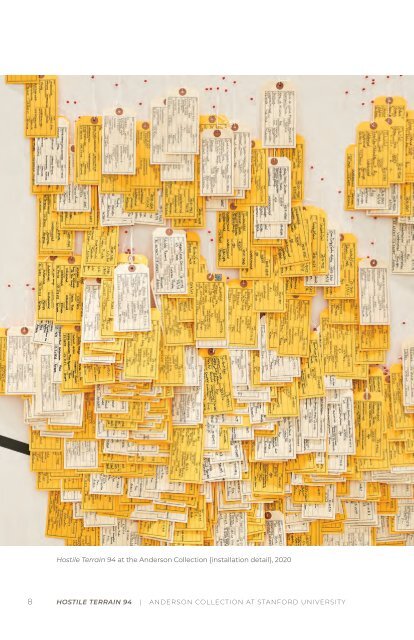

Hostile Terrain 94

Hostile Terrain 94 is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project. The installation is composed of more than 3,200 hand-written toe tags filled out by the community, each representing a migrant who has died trying to cross the US-Mexico border at the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019. The exhibition is installed on the first floor and the accompanying publication was written by both graduate and undergraduate students at Stanford University.

Hostile Terrain 94 is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project. The installation is composed of more than 3,200 hand-written toe tags filled out by the community, each representing a migrant who has died trying to cross the US-Mexico border at the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019. The exhibition is installed on the first floor and the accompanying publication was written by both graduate and undergraduate students at Stanford University.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A CLIFF NEAR CABORCA<br />

JON AYON ALONSO<br />

My father grew up in San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico. The Sonoran<br />

Desert, a landscape of extremes—hot, cold, bright, dark—is his most<br />

familiar terrain. As a child, I made the journey southward to Mexico with<br />

my family many times, our car weighted down with bulk bags of rice,<br />

beans, and flour, our tires overinflated so that the car’s bottom wouldn’t<br />

drag and spark along the road. Our visits felt joyous and celebratory as<br />

we reunited with our family on the other side of the border. It was only<br />

later I learned of the fear that oppressed my father on those journeys.<br />

While interviewing him for a film I made about immigration, he<br />

revealed to me that for fourteen years of my childhood, my parents had<br />

been undocumented. They had kept this fact hidden from me, so deep<br />

was their fear I could accidentally betray them.<br />

Despite never having been expressed or acknowledged, this fear<br />

permeated the fabric of our family. I didn’t have to see gravestones or<br />

fatality rates to be reminded that we were the unfortunately fortunate<br />

ones, and that this fortune came with both debt and duty: a debt to<br />

those who did not make it across, and to the family we left behind;<br />

a duty to make the most of our opportunity living in a capitalist<br />

superpower—a duty to work, to consume, to provide. Homes can be<br />

traumatic places for first-generation immigrant children. They can<br />

buckle and cave from the pressure to make every choice count. You<br />

aren’t allowed to dream in a childhood where dreams have died for<br />

your opportunities. Even now, as a grown man and father myself, I am<br />

influenced by these forces with every decision I make, every opportunity<br />

I accept or decline. I constantly fight my instinct to keep my head down,<br />

stay quiet, and survive. And I often wage this daily fight alone, as one of<br />

the only first-gen Latinx students in my graduate classes at Stanford.<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection {installation detail}, 2020<br />

8 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 9