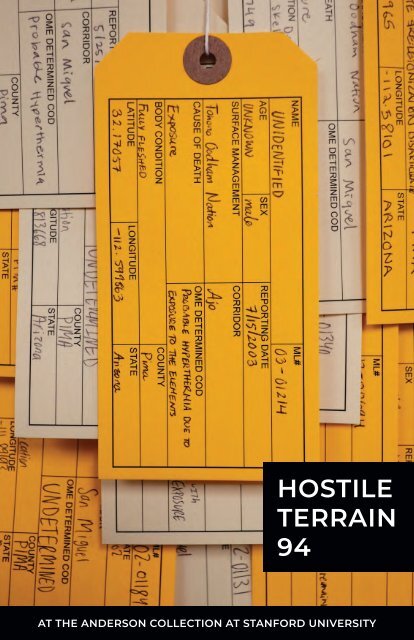

Hostile Terrain 94

Hostile Terrain 94 is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project. The installation is composed of more than 3,200 hand-written toe tags filled out by the community, each representing a migrant who has died trying to cross the US-Mexico border at the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019. The exhibition is installed on the first floor and the accompanying publication was written by both graduate and undergraduate students at Stanford University.

Hostile Terrain 94 is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project. The installation is composed of more than 3,200 hand-written toe tags filled out by the community, each representing a migrant who has died trying to cross the US-Mexico border at the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2019. The exhibition is installed on the first floor and the accompanying publication was written by both graduate and undergraduate students at Stanford University.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

HOSTILE<br />

TERRAIN<br />

<strong>94</strong><br />

AT THE ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY

The Anderson Collection at Stanford University is one of more than<br />

one hundred institutions across the world hosting <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> in<br />

2020 and 2021. The museum is proud to exhibit this project—directed<br />

by University of California, Los Angeles anthropologist Jason De León—<br />

which grew out of years of social and anthropological research along the<br />

US-Mexico border.<br />

Migration is often depicted in numbers and percentages, without<br />

names or faces or histories of lives lived. <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> turns<br />

that data into a visual representation of individual migrants, at once<br />

absolutely horrifying and strikingly beautiful. It is in that beauty that<br />

we are asked to look closer, to look at the black line, the dots, and the<br />

thousands of hanging rectangles as they shift ever so slightly with the<br />

movement of passersby.<br />

It wasn’t until I began participating in the project directly that the power<br />

of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> became clear to me. I had watched videos, read<br />

articles, even seen a prototype of the project in person. Though many<br />

things surfaced for me during my research of this project, not until I<br />

began writing down the names on tags did the people, the words, and<br />

the lives of each individual became so heartbreakingly real for me. I<br />

spent many nights with a cramping hand, copying names of the dead<br />

from a spreadsheet to a toe tag. As the nights went on, my seven-yearold<br />

daughter became more and more interested in the content I was<br />

writing. She began asking to see tags as I finished them, sometimes<br />

reading them in her head and sometimes reading aloud the names of<br />

people whose lives were diminished to a coroner’s note. I wonder how<br />

many people have spoken their names out loud.<br />

This publication is written entirely by students at Stanford University.<br />

The first essay gives an overview of how the project came to be and how<br />

Koji Lau-Ozawa, a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology,<br />

COVER: Toe tags, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.<br />

HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY<br />

1

ought <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> to the Anderson Collection. The second<br />

essay, by MFA candidate in Documentary Film and Video Studies Jon<br />

Ayon Alonso, is a reflection on his and his family’s personal experience<br />

of the US-Mexico border. In the essays that follow, three undergraduate<br />

students look at <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> in the context of the museum’s<br />

collection. Ekalan Hou, Melissa Santos, and Georgia Gardner use<br />

individual works in the Anderson Collection as conduits for deeper<br />

understanding of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>, drawing parallels through the<br />

iconography in a painting, the tactile fragility of a sculpture, and the role<br />

of the grid in contemporary art. Each of the five student participants has<br />

dedicated many months to this project—filling out tags, researching,<br />

reading, looking at art, and writing. These are the same months when<br />

COVID-19 became a global pandemic and students were sent home to<br />

finish the academic year. The murder of George Floyd, which catapulted<br />

the United States into protests and riots, and an impending presidential<br />

election, different from any other, have compounded this already<br />

challenging situation. The Anderson Collection thanks these students<br />

for their dedication and scholarship, which have made this publication<br />

and this project a reality.<br />

Aimee Shapiro<br />

Director of Programming and Engagement<br />

Anderson Collection at Stanford University<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection {installation view}, 2020<br />

2 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 3

BRINGING HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> TO THE<br />

STANFORD COMMUNITY<br />

KOJI LAU-OZAWA<br />

When I first saw the <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> installation in a photograph, I did<br />

not understand what I was looking at. As one of my advisors outlined<br />

the meaning behind the mass of orange and tan tags, it dawned on me<br />

that each of those tags represented a life lost as the result of US border<br />

policies. Each signified a life that was filled with triumphs and sorrows,<br />

passions and fears, hopes and disappointments. I was overwhelmed by<br />

the immensity of the loss.<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> is a production of the Undocumented Migration Project<br />

(UMP). Led by scholar Jason De León, the UMP is an anthropological<br />

study of clandestine movement between Latin America and the<br />

United States. Drawing on a range of disciplines, from archaeology and<br />

forensic sciences to ethnography and visual anthropology, the UMP<br />

strives not only to understand the processes of migration and the lives<br />

of migrants but also to educate the public through multiple mediums.<br />

Earlier exhibitions by the UMP—such as State of Exception / Estado<br />

de Excepción, which featured hundreds of backpacks and ephemera<br />

left behind by migrants crossing the US-Mexico border—have been<br />

presented across the United States. While powerful, such traveling<br />

exhibitions are cost prohibitive for many institutions to host, limiting the<br />

public’s exposure to these visual statements.<br />

In response to this challenge, the UMP team developed <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong><br />

<strong>94</strong> as a multimedia exhibit that relies on community participation<br />

for completion and is much more affordable to host. It consists of<br />

more than 3,200 toe tags hung across a wall map of the US-Mexico<br />

border; each tag is pinned to the map according to coordinates for<br />

Toe tags, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>, 2020<br />

4 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 5

the location where the body of a person who died crossing the border<br />

was found. Between 19<strong>94</strong> and today, the death toll from attempted<br />

border crossings has risen continuously, driven by the official federal<br />

policy of Prevention Through Deterrence. On each tag, volunteers fill in<br />

information collected from coroners’ offices, detailing the name, cause<br />

of death, and condition of the person found. Tan tags are for those<br />

who could be identified; orange are for those who remain unknown.<br />

What is astounding is not only the striking result—this immense map<br />

of death—but also the exhibition’s wide reach, extending to the dozens<br />

of volunteers who completed the tags by hand: each tag completed<br />

means a life contemplated.<br />

Though our initial plans for intensive in-person programing in the<br />

spring quarter of 2020 were interrupted due to pandemic-related<br />

restrictions, the organizing team did not lose a single step. With a<br />

tremendous amount of effort and time, safety protocols were enacted,<br />

volunteers contacted, and thousands of tags filled out—a testament to<br />

the commitment of the Stanford community, as well as the importance<br />

of the subject matter. Whatever your thoughts about immigration<br />

policy might be, we ask you to look at this exhibit, sit with it, allow it to<br />

overwhelm, and then reflect on the lives represented.<br />

I first heard of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> in January 2019. Understanding the<br />

plan for the exhibition to hang simultaneously at nearly one hundred<br />

institutions across the world, I was eager to get Stanford involved. Over<br />

the next six months, I emailed every department, program, building<br />

manager, and program initiative across campus that I could think<br />

of, asking if there was interest in hosting the exhibit, and a place to<br />

hang the twenty-foot wall map. Most emails went unanswered, and<br />

phone calls unreturned—that is, until June 2019, when my inquiry was<br />

forwarded to the Anderson Collection.<br />

KOJI LAU-OZAWA is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at<br />

Stanford, who studies the archaeology of Japanese American Incarceration.<br />

By July 2019, the Anderson Collection had reviewed the project and<br />

enthusiastically agreed to host the exhibition in fall 2020. By the end<br />

of summer 2019, several colleagues joined with me to create a core<br />

organizing team. Departments and programs joined to cosponsor the<br />

exhibition, including our current partners The Bill Lane Center of the<br />

American West, the Department of Anthropology, The Office of the<br />

Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, the School of Humanities<br />

and Sciences, the Bechtel International Center, and the Center for<br />

Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.<br />

6 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 7

A CLIFF NEAR CABORCA<br />

JON AYON ALONSO<br />

My father grew up in San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico. The Sonoran<br />

Desert, a landscape of extremes—hot, cold, bright, dark—is his most<br />

familiar terrain. As a child, I made the journey southward to Mexico with<br />

my family many times, our car weighted down with bulk bags of rice,<br />

beans, and flour, our tires overinflated so that the car’s bottom wouldn’t<br />

drag and spark along the road. Our visits felt joyous and celebratory as<br />

we reunited with our family on the other side of the border. It was only<br />

later I learned of the fear that oppressed my father on those journeys.<br />

While interviewing him for a film I made about immigration, he<br />

revealed to me that for fourteen years of my childhood, my parents had<br />

been undocumented. They had kept this fact hidden from me, so deep<br />

was their fear I could accidentally betray them.<br />

Despite never having been expressed or acknowledged, this fear<br />

permeated the fabric of our family. I didn’t have to see gravestones or<br />

fatality rates to be reminded that we were the unfortunately fortunate<br />

ones, and that this fortune came with both debt and duty: a debt to<br />

those who did not make it across, and to the family we left behind;<br />

a duty to make the most of our opportunity living in a capitalist<br />

superpower—a duty to work, to consume, to provide. Homes can be<br />

traumatic places for first-generation immigrant children. They can<br />

buckle and cave from the pressure to make every choice count. You<br />

aren’t allowed to dream in a childhood where dreams have died for<br />

your opportunities. Even now, as a grown man and father myself, I am<br />

influenced by these forces with every decision I make, every opportunity<br />

I accept or decline. I constantly fight my instinct to keep my head down,<br />

stay quiet, and survive. And I often wage this daily fight alone, as one of<br />

the only first-gen Latinx students in my graduate classes at Stanford.<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection {installation detail}, 2020<br />

8 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 9

I still go visit my family on the other side of the border as often as I can.<br />

When I cross the border now, as an adult, I feel my father’s fear at each<br />

checkpoint, with each passing siren. Recently, I traveled south to visit<br />

one of the tribes from which my father descended, the Comcáac, who<br />

live along the Sonoran coast. As I drove down the main highways (paved<br />

over ancient Indigenous trade routes) toward the coast, I stopped at a<br />

huge altar cut into the side of a cliff near Caborca. A mural painting of La<br />

Virgen de Guadalupe looms two stories high, and as you climb the stairs<br />

to reach the mural, you pass hundreds of candles and white stones. Each<br />

stone is engraved with a name; each represents a life lost. Many of those<br />

lost are migrants—victims of unjust trade agreements, imperialism, and<br />

repressive immigration policies. The altar serves as a place of respite and<br />

reflection for migrants taking the journey toward Arizona, as well as a<br />

place for surviving families to mourn. At the time of my visit, the stones<br />

were so numerous they were in piles. I have carried the weight of those<br />

stones with me my entire life; I carry them with me today.<br />

BEARING WITNESS: HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong><br />

AND THE COAT II<br />

EKALAN HOU<br />

“No survey is done near the body to look for additional personal effects.<br />

The trail is not checked for other people or corpses. Some photos are<br />

taken and geographic coordinates are recorded. It takes a total of five<br />

minutes.” 1<br />

Such is the extent of the investigation of migrant deaths in the Sonoran<br />

Desert, as anthropologist Jason De León witnesses and recounts in<br />

The Land of Open Graves, and such lack I transcribe onto orange and<br />

manila toe tags. Jaime Pascual Gomez-Ruiz’s pendejadas––his jokes<br />

JON AYON ALONSO is a master’s candidate in Documentary Film and Video<br />

Studies at Stanford University.<br />

Figure 1. Toe tags, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection {detail}, 2020<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

1<br />

Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Oakland:<br />

University of California Press, 2015), 215.<br />

10 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 11

and banter––evaporate and condense into numbers in boxes; his<br />

personality is stripped to a bare scaffolding that medical examiners call<br />

“skeletonization.” The only legal documentation he will ever receive in<br />

this country is a record of his death. 2<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> (fig. 1), organized by the Undocumented Migration<br />

Project, is an installation that documents and plots the structural<br />

violence faced by migrants crossing the US-Mexico border. While<br />

claiming to discourage undocumented entries into the United States,<br />

the US Border Patrol’s immigration enforcement strategy, known as<br />

Prevention Through Deterrence, redirects migrants from urban ports<br />

of entry and compels them to traverse the Sonoran Desert in Arizona,<br />

where the temperature fluctuates between 50 and 120 degrees<br />

Fahrenheit. 3 Border Patrol uses nature as an alibi and disguises migrant<br />

deaths as unfortunate “accidents” that occur on its noble path to<br />

suppress illegal immigration. 4 The dehumanization of these migrants,<br />

who are treated as parasitic numbers on a federal security graph and<br />

whose personal belongings are categorized as “trash” or blights on the<br />

environment that consumed them, is made manifest in <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong><br />

<strong>94</strong>. 5 The impersonal and indifferent toe tags reflect the government’s<br />

elision of the migrants’ personhood––their lives are defined by<br />

identification cards that they will never receive.<br />

Overcoat,” a likely source of inspiration for Guston’s painting, the value of<br />

human life is absorbed by an object. 6<br />

The clerk in Gogol’s story, Akaky Akakievich, is treated by others<br />

according to the condition of his coat. When he wears a “rust- and<br />

mud-colored” coat that is stained with rubbish—akin to the one painted<br />

by Guston—he is ridiculed and overlooked. 7 Similarly, as migrants are<br />

measured by their lack of legal status and their gritty belongings in the<br />

desert, their erasures––sanitation by another name––seem justified.<br />

A painting from the Anderson Collection that explores the difficulty of<br />

surviving in a cruel and apathetic world is Philip Guston’s The Coat II<br />

(fig. 2). The depicted coat, like the toe tags, is synecdochic: it is a proxy<br />

that signifies and displaces the human body; its presence renders the<br />

corporeal invisible and negligible. As in Nikolai Gogol’s short story “The<br />

Figure 2. Philip Guston, The Coat II, 1977, oil on canvas, 69 1⁄8 x 92 1⁄8 in., Anderson<br />

Collection at Stanford University, Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, and Mary<br />

Patricia Anderson Pence, 2014.1.047. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser &<br />

Wirth. Photo: M. Lee Fatheree.<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

2<br />

The “ML#” on the toe tag—the case number assigned to each migrant brought into the<br />

medical examiner’s office—is an abbreviation for “medico-legal number” [my emphasis].<br />

3<br />

“Background,” Undocumented Migration Project, https://www.undocumentedmigrationproject.org/background,<br />

[July 25, 2020], and De León, The Land of Open Graves, 75.<br />

4<br />

De León, The Land of Open Graves, 274.<br />

5<br />

Ibid., 201.<br />

Both <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> and The Coat II document the hostility of their<br />

respective societies. Guston considers the primary function of art as<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

6<br />

Magdalena Dabrowski, The Drawings of Philip Guston (New York: The Museum of Modern Art,<br />

1988), 14.<br />

7<br />

Nikolai Gogol, The Overcoat (London: Merlin Press, 1956), 12.<br />

12 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 13

earing witness to lives “made up of the most extreme cruelties.” 8 His<br />

coat, which wades in blood and whose sleeves rupture into wounds,<br />

betokens Gogol’s critique of the “savage brutality there lurks beneath<br />

the most refined, cultured politeness.” 9 In accordance with Gogol’s<br />

statement, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> reveals the violence that the United<br />

States inflicts upon migrants in the name of national security. By<br />

declaring a “war on immigration” or enforcing a “zero tolerance”<br />

policy, the government pretends to enter into a state of crisis to strip<br />

migrants of their human rights. In a “state of exception,” not only<br />

are the “exceptional” made excludable, killable, and disposable but<br />

the government also reinforces its power. 10 <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> resists<br />

justifications for migrant deaths—effectively murders—and demands<br />

justice for the victims who lay rotting on the desert floor––in plain sight<br />

but with no witnesses, human but negligible.<br />

In addition to evincing a reality to which people have been willfully blind,<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> insists on structural and nonmetaphorical changes.<br />

It destabilizes statistics put forth by the government—statistics that<br />

highlight a decrease in illegal border crossings but conceal the death<br />

tally in the Sonoran Desert. It demonstrates the inefficacy of Prevention<br />

Through Deterrence, as migrants are motivated not by the convenience<br />

of the journey but by a global economy that pushes them to seek work<br />

in the United States and creates a need for cheap labor there despite<br />

Americans’ hypocritical distaste for undocumented laborers. 11 <strong>Hostile</strong><br />

<strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> calls for a reevaluation of our current border and economic<br />

policies and a correction to the portrayal of undocumented people as<br />

erasable and their suffering as intangible. It also comments explicitly on<br />

the upcoming general election and against President Donald Trump’s<br />

manipulation of “states of exception” to dehumanize migrants. <strong>Hostile</strong><br />

<strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> does not disguise the political nature of the project to uphold<br />

the aloof immaculateness of “art”; its purpose is to activate change.<br />

Guston also sees the aim of his art as “un-numbing” his audience––<br />

awakening viewers from inertia and dissolving the desensitizing cloak<br />

of the status quo. 12 He deconstructs “cultural shibboleths” and positions<br />

himself against society. 13 Guston renounces the “soothing lullaby” of<br />

common perceptions and the finality of political dictations; he makes all<br />

the elements in The Coat II morphological. 14 Guston crucifies everyday<br />

objects: The bottom hem of the coat becomes two planks of wood<br />

nailed together by black buttons; the sleeves appear stiff and fleshy<br />

all at once; and the shoes are semblances of bread. The black dots are<br />

incisions used to puncture the “normal.” His “wobbly” painting holds<br />

the “promise of continuity” for which <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> also hopes. 15<br />

Just as De León intends to “sneak back and forth across the border<br />

between ‘accepted discourse and excluded discourse’ ” to generate<br />

new knowledge and new forms of cultural understanding, 16 Guston,<br />

too, seeks to suspend history in a state of constant redefinition. Guston<br />

writes that “history is not a cat that follows you around” 17 —it always lies<br />

ahead, anticipating your arrival.<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

8<br />

Dore Ashton, A Critical Study of Philip Guston (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990),<br />

177. In an interview with Morton Feldman, Guston said, “I began to see all of life really as a vast<br />

concentration camp. And everybody is numbed, you know. Then I thought, ‘Well, that’s the<br />

only reason to be an artist: to escape, to bear witness to this.’ ” See also Clark Coolidge, Philip<br />

Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations (Berkeley: University of California<br />

Press, 2011), 81.<br />

9<br />

Gogol, The Overcoat, 10.<br />

10<br />

Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press: 2005). See<br />

also, Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford<br />

University Press, 1998); Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of<br />

Sovereignty (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press: 2005).<br />

11<br />

Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004), 22.<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

12<br />

Coolidge, Philip Guston, 81.<br />

13<br />

Ashton, A Critical Study of Philip Guston, 179.<br />

14<br />

Philip Guston, “Studio Notes December 8th, 1978,” quoted in Coolidge, Philip Guston, 314.<br />

15<br />

Coolidge, Philip Guston, 195.<br />

16<br />

De León, The Land of Open Graves, 14.<br />

17<br />

Coolidge, Philip Guston, 171.<br />

14 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 15

EKALAN HOU is a junior double majoring in English and Art History. She is a<br />

Student Guide at the Cantor Arts Center and the Anderson Collection.<br />

OTHER WORKS CONSULTED:<br />

Aviles, Mary. “Data Visualization as an Act of Witnessing.” Nightingale, March 4,<br />

2020. https://medium.com/nightingale/data-visualization-as-an-act-ofwitnessing-33e346f5e437.<br />

De León, Jason, Cameron Gokee, and Ashley Schubert. “ ‘By the Time I Get to<br />

Arizona’: Citizenship, Materiality, and Contested Identities along the US-<br />

Mexico Border.” Anthropological Quarterly 88, no. 2 (2015): 445–79. https://doi.<br />

org/10.1353/anq.2015.0022.<br />

De León, Jason, Cameron Gokee, and Anna Forringer-Beal. “ ‘Disruption,’ Use Wear,<br />

and Migrant Habitus in the Sonoran Desert.” In Migration and Disruptions,<br />

edited by Brenda J. Baker and Takeyuki Tsuda, 145–78. Gainesville: University<br />

Press of Florida, 2015. https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813060804.003.0007.<br />

EMBODIMENT: MANUEL NERI, HOSTILE<br />

TERRAIN <strong>94</strong>, AND THE DEPICTION OF<br />

VIOLENCE IN ART<br />

MELISSA SANTOS<br />

The human body has long been used in art to explore the human<br />

condition—life and death, the personal and the political. In paintings<br />

and in sculpture, the depiction of the body beckons us to reflect on<br />

our own fragility and humanity. Manuel Neri’s life-size sculptures of<br />

women in plaster are an example of an artist’s attempt to capture body<br />

language and movement. The textured surface of pieces like Marble Relief<br />

Maquette No. 3 (1983) (fig. 3) and Standing Figure II (1982) (fig. 4) evidence<br />

his handiwork and evoke a profound emotional response; the sculptures<br />

convey the sense of intimacy Neri felt with his subjects, such as his lifelong<br />

muse, Mary Julia Klimenko, who posed for both aforementioned works. 1<br />

Gokee, Cameron, and Jason De León. “Sites of Contention: Archaeological<br />

Classification and Political Discourse in the US-Mexico Borderlands.” Journal<br />

of Contemporary Archaeology 1, no. 1 (2014): 133–63. https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.<br />

v1i1.133.<br />

Gokee, Cameron, Haeden Stewart, and Jason De León. “Scales of Suffering in the<br />

US-Mexico Borderlands.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 2020.<br />

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-019-00535-6.<br />

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to<br />

Precision-Nested Scales.” Common Knowledge 18, no. 3 (2012), 505–24. https://<br />

doi.org/10.1215/0961754x-1630424.<br />

Toe tags, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection {detail}, 2020<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

1<br />

Sidney Simon, “Standing Figure II,” Anderson Collection at Stanford University website, accessed<br />

July 21 2020, https://anderson.stanford.edu/collection/untitled-standing-figure-by-manuel-neri/.<br />

16 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 17

things that come to mind. However, each tag on the wall represents the<br />

recovered body of an undocumented migrant who died between the<br />

mid-1990s and 2019 while crossing the border.<br />

Each of these migrants entered the “hostile terrain” of the Sonoran<br />

Desert because American policy left them with few alternatives. In<br />

19<strong>94</strong>, the United States closed highly frequented border crossing<br />

points under a campaign called Prevention Through Deterrence; it<br />

was meant to discourage undocumented migrants from crossing the<br />

border. Rather than deterring migrants, however, the policy merely<br />

heightened the risks for those attempting border crossings—including<br />

more than six million people since 2000—as they searched for routes<br />

through harsh, remote regions that pose greater risk of dehydration<br />

and hyperthermia. Because the resulting migrant deaths are portrayed<br />

as “natural,” they are “easily denied by state actors and erased by the<br />

desert environment.” 2<br />

Figure 3. (left) Manuel Neri, Marble Relief Maquette, No. 3, 1983, bronze with Alborada<br />

patina, oil-based pigments with yellow glaze, cast 2013, patina 2016, ed. 1/4, 27 ½ x 9 ¾ x<br />

4 in., Anderson Collection at Stanford University, Gift of the Manuel Neri Trust, 2017.2.03c.<br />

© The Manuel Neri Trust. Photo: M. Lee Fatheree. Figure 4. (right) Manuel Neri, Standing<br />

Figure II, 1982, pigment on plaster, 69 ¼ x 17 7⁄8 x 19 ½ in., Anderson Collection at Stanford<br />

University, Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, and Mary Patricia Anderson<br />

Pence, 2014.1.059. © The Manuel Neri Trust. Photo: Ian Reeves.<br />

Upon closer examination, the bodily violence attributed to natural<br />

causes is actually a product of structural violence: policies like Prevention<br />

Through Deterrence; ramifications from the 19<strong>94</strong> North American Free<br />

Trade Agreement, such as cheap American imports, out-of-work peasant<br />

farmers, and Mexico’s failing economy, all of which spurred migration to<br />

the United States; and interventionist US policies that created instability<br />

and danger in many Central American countries. 3<br />

Although Neri’s work is beautiful, it also suggests vulnerability: one cannot<br />

help but consider the violence in the scratches and scrapes on the<br />

surface, the missing face and limbs, the corpus forever entrapped in a<br />

plaster shell.<br />

Like the chips and gouges in Neri’s plaster sculptures, the details of<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> prompt thoughts of violence and suffering. When one<br />

first encounters the installation—a collection of 3,200 toe tags pinned<br />

across a map of the US-Mexico border—bodies may not be the first<br />

Even after their deaths, the undocumented migrants represented by<br />

the tags continue to suffer from what anthropologist Jason De León<br />

calls “necroviolence,” or violence produced by treating corpses in a way<br />

that is offensive, sacrilegious, or inhumane, as their bodies are often<br />

decomposed, degraded by the unforgiving desert sun, or defiled by<br />

animals. 4 This is especially true for those represented by orange tags,<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

2<br />

Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Oakland:<br />

University of California Press, 2015), 16.<br />

3<br />

Ibid., 6.<br />

4<br />

De León, The Land of Open Graves, 69.<br />

18 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 19

whose bodies were unable to be identified; for each of those bodies,<br />

someone mourns the unresolved loss of a child, parent, sibling, or friend.<br />

As De León writes, families who lose a loved one yet never receive a body<br />

to bury are not only denied the funeral rites associated with mourning<br />

but deprived of the ability to “make sense of the life and death of the<br />

deceased.” 5 The postmortem violence of policies like Prevention Through<br />

Deterrence robs undocumented migrants of their dignity even in death.<br />

Unlike Neri’s sculptures, whose suggestions of violence are limited to<br />

the appearance of their plaster limbs and skin, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> asks<br />

us to consider physical harm well hidden by politics and bureaucracy.<br />

In the absence of the figure, we must consider bodies that, though not<br />

materially present, constituted real people who endured real suffering.<br />

We are charged with remembering and memorializing each person<br />

represented by a tag. Most importantly, we are urged to consider the<br />

human cost of federal policies and reexamine where our country stands<br />

on human rights issues, especially at our border—a responsibility that<br />

extends beyond the museum walls, and long after the installation of<br />

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>.<br />

MELISSA SANTOS is a Student Guide at the museums and a Stanford senior<br />

currently residing in Los Angeles; she will receive her bachelor’s in Psychology<br />

and master’s in Sociology in June 2021.<br />

FILL IN THE BLANKS: PEOPLE AND LINES<br />

IN JASON DE LEÓN’S HOSTILE TERRAIN<br />

<strong>94</strong> AND AGNES MARTIN’S UNTITLED #21<br />

GEORGIA GARDNER<br />

The movement of people across the United States’ Southern border<br />

has become an unquestionably controversial topic in recent years.<br />

The reasons are many and varied, but the politicization of the border<br />

crisis has allowed stakeholders other than immigrants to describe and<br />

define the issue, as well as prescribe solutions. People have become<br />

“aliens,” “illegals,” numbers, and pawns for political advancement. Their<br />

intentions and morality have been challenged by strangers; their bodies<br />

have been brutalized by heat, thirst, and starvation; and, above all, their<br />

humanity has been erased.<br />

With <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>, anthropologist and curator Jason De León and<br />

the Undocumented Migration Project have zeroed in on one especially<br />

barren section of land that straddles the US-Mexico border to illuminate<br />

the obscured human toll of one particularly brutal strategy of border<br />

security. This strategy is called Prevention Through Deterrence, or PTD.<br />

PTD is a Band-Aid on a bullet wound, claiming to discourage and hinder<br />

unofficial movement across the border but instead merely making<br />

the passage more perilous. The infamously arid, empty, inhospitable,<br />

uninhabitable Sonoran Desert spans the border regions of Mexico and<br />

Arizona, serving as an environmental barrier that impedes passage<br />

between the two countries. Relying on the false but persistent notion<br />

of “empty land” as unclaimed, unregulated space—a notion used by<br />

colonizers to legitimize expansionist desires and displace indigenous<br />

citizens—officers and legislators attempt to ignore and even hide the<br />

large and real human toll PTD has taken.<br />

5<br />

Ibid., 71.<br />

In its beginning stages, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> seemed to mirror this image<br />

of an empty desert. A preliminary draft of the piece included a thick,<br />

20 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 21

lack line representing the border, but disregarded the landscape of the<br />

Sonoran Desert (fig. 5), with its scorched, dusty soil; its blazing, cloudless<br />

skies; and its smattering of unfriendly cacti and grasses. Unrepresented,<br />

too, were the personalities, passions, and pains of the people who<br />

perished there, or of those who survived the trek across the expanse. De<br />

León wrote, “Those who live and die in the desert have names, faces, and<br />

families,” acknowledging that these essential human features are not<br />

visible in the assemblage of lines that form the foundation of the project. 1<br />

The grid, employed in both <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> (to aid installation of tags)<br />

and the Anderson Collection’s Untitled #21 (fig. 6) by American painter<br />

Agnes Martin, is a sterile, technical tool used to calculate and exact.<br />

Associated with mathematics, precise measurements, and durable<br />

netting and fencing, the grid does not naturally engender feelings of<br />

freedom, beauty, or humanity. However, in the 1960s, Martin chose the<br />

Figure 6. Agnes Martin, Untitled #21, 1980, acrylic, gesso & graphite on canvas, 72 x 72<br />

in., Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, and Mary Patricia Anderson Pence,<br />

2014.1.110. © Estate of Agnes Martin / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

Figure 5. Scale drawing of installation. The small triangles on this grid would be replaced by<br />

with hanging manila or orange toe tags. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.<br />

grid as the center of her artistic vocabulary. Without brushstrokes or<br />

signatures, her work seems, at first, predictably and thoroughly void of<br />

humanity. The bulk of Martin’s oeuvre features large, square canvases<br />

filled by grids and stripes in sepia tones and the paler versions of the<br />

primary colors: baby blues, soft pinks, and glowing yellows. While the<br />

works are undeniably abstract, some viewers see everyday patterns, “like<br />

the lines of a musical staff, or an accounting ledger, or a school notebook.” 2<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

1<br />

Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Oakland:<br />

University of California Press, 2015), 5.<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

2<br />

Holland Cotter, “The Joy of Reading Between Agnes Martin’s Lines,” New York Times, October<br />

6, 2016.<br />

22 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 23

Untitled #21, currently featured in the Anderson Collection, is a tranquil<br />

and luminous piece Martin painted in 1980 on one of her signature<br />

72-by-72-inch canvases. The artist made the painting in the New<br />

Mexican desert, where she settled permanently in pursuit of quiet,<br />

solitude, and communion with nature. She used graphite to cast gray,<br />

horizontal lines across the canvas, which she filled with washed-out<br />

stains of pink, yellow, and blue separated by empty lanes of canvas. 3 The<br />

infinitely subtle, disappearing impressions of color repeat predictably<br />

and symmetrically down the length of the canvas. Only when one looks<br />

at the painting more closely are the imperfections and personality of<br />

the piece perceptible: The previously unswerving gray lines wiggle<br />

slightly, some sections darker and thicker than others. The slender<br />

bands of color transform from razor-edged rulers to waving ribbons,<br />

the color within beginning to flicker. Untitled #21 becomes a beautifully<br />

flawed human creation rather than a uniform pattern that could be<br />

replicated by a machine.<br />

Just as Untitled #21 requires a viewer’s attention and participation to<br />

uncover its humanity, <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> involves the public directly to<br />

saturate the blank grid of a map with names, numbers, and personal<br />

information. Members of each community where <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong><br />

lands fill the sterile map with pushpins and toe tags. The heavy layer of<br />

tags gives form to the individuals and stories that populate the so-called<br />

vacant land. All 3,200 people whose lives were lost under implementation<br />

of PTD—whose mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, and children miss<br />

them every day, and whose bodies were left to be discovered or<br />

disappear in the baking heat—are represented on the wall. Their names,<br />

ages, genders, and causes of death have been researched, written,<br />

and attached to tags pinned on the map exactly where they died. The<br />

participatory element, whereby community members transfer the<br />

facts of the thousands of victims’ lives and deaths onto tags is an act of<br />

____________________________________________________<br />

3<br />

Peter Schjeldahl,“Agnes Martin, a Matter-of-Fact Mystic,” New Yorker, October 17, 2016.<br />

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/17/agnes-martin-a-matter-of-fact-mystic.<br />

remembrance, honor, and mourning. Participants carefully and lovingly<br />

document the undocumented, filling the empty desert with people.<br />

The heart of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> lies in the tragic, anthropological<br />

component layered atop the grid, but the piece would not be the same<br />

without its technical foundation. Similarly, the heart of Untitled #21 is<br />

uncovered in the pause, through reflection, focus, and calm, even as<br />

its utilitarian formal elements fortify its value. It is the intersection of<br />

perfection and chaos, the grid and the wild, the mathematical and the<br />

real, that makes Martin’s work so special, and what enables De León’s<br />

message to reverberate so loudly and poignantly.<br />

GEORGIA GARDNER is a junior studying Art History and International Relations<br />

and is a Student Guide at the Cantor Arts Center and Anderson Collection<br />

during her final two years at Stanford.<br />

OTHER WORKS CONSULTED:<br />

Aviles, Mary. “Data Visualization as an Act of Witnessing.” Nightingale. March<br />

04, 2020. https://medium.com/nightingale/data-visualization-as-an-act-ofwitnessing-33e346f5e437.<br />

Cotter, Holland. “The Joy of Reading Between Agnes Martin’s Lines.” New York<br />

Times. October 6, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/07/arts/design/thejoy-of-reading-between-agnes-martins-lines.html.<br />

De León, Jason. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail<br />

(Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 5.<br />

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Agnes Martin, a Matter-of-Fact Mystic.” New Yorker. October 17,<br />

2016. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/17/agnes-martin-a-matterof-fact-mystic.<br />

Tate. 2012. “Who Is Agnes Martin” Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tatemodern/exhibition/agnes-martin/who-is-agnes-martin.<br />

24 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY 25

<strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> {installation view}, Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.

The Anderson Collection at Stanford University is grateful for a dedicated<br />

and passionate organizing team that helped bring this project to fruition.<br />

The museum thanks Koji Lau-Ozawa, Valentina Ramia, Gina Hernandez,<br />

and Jon Ayon Alonso for their determination, resolve, and perseverance to<br />

see this project through a global pandemic, remote learning, area wildfires,<br />

and an election year like no other. Thank you to Mark Shunney for his<br />

attention to detail and concentration while installing the grid, pins, and<br />

tags of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong>.<br />

The Undocumented Migration Project Exhibition at Stanford, a class listed<br />

in Chicano/Latino Politics/CSRE, is being taught by Gina Hernandez and<br />

Koji Lau-Ozawa in fall quarter 2020 on occasion of the <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong><br />

installation at the Anderson Collection. The museum thanks the students<br />

in this class for their participation in the installation and excitement about<br />

studying this project.<br />

Thank you to our partners at Stanford: The Bill Lane Center for the American<br />

West, the Department of Anthropology, The Office of the Vice Provost for<br />

Undergraduate Education, the School of the Humanities and Sciences, the<br />

Bechtel International Center, and the Center for Comparative Studies in<br />

Race and Ethnicity.<br />

The Anderson Collection at Stanford University is grateful for the advocates,<br />

activists, and humanitarians whose work respects and fights for the rights<br />

of migrants on the US-Mexico border.<br />

The museum is grateful for support from the Drs. Ben and A. Jess Shenson<br />

Fund and the Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson Charitable Foundation<br />

that made this publication possible.<br />

This brochure is published on the occasion of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection<br />

at Stanford University fall 2020-spring 2021.<br />

design: Pink Top<br />

project management: Aimee Shapiro<br />

copy editing: Anne C. Ray<br />

All photos of <strong>Hostile</strong> <strong>Terrain</strong> <strong>94</strong> at the Anderson Collection by<br />

Impart Photography unless otherwise noted.<br />

© 2020 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University<br />

28 HOSTILE TERRAIN <strong>94</strong> | ANDERSON COLLECTION AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY