Apothecary 2020

Journal of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries for Master's Year 2019-20

Journal of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries for Master's Year 2019-20

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

their empirical experiences of successful remedies in<br />

new ways. This certainly seems to have been the case for<br />

Boghurst who stated in his preface: “I have writt<br />

nothing from hearsay or from bookes or from the<br />

testimony of others or my own conceit, but all and onely<br />

from experience and triall.” This does not mean that<br />

Boghurst, and others, wholly abandoned blood-letting,<br />

blistering, purging or Hippocratic ideas of regimen and<br />

diet, and a reliance on humoral theory seems to have<br />

held sway. Thomas Sydenham wrote about how he<br />

evaluated blood letting against inducing a diaphoresis<br />

(intense sweating) or in Sydenham’s words “dissipation<br />

of the Pestilential Ferment by sweat”. He compares the<br />

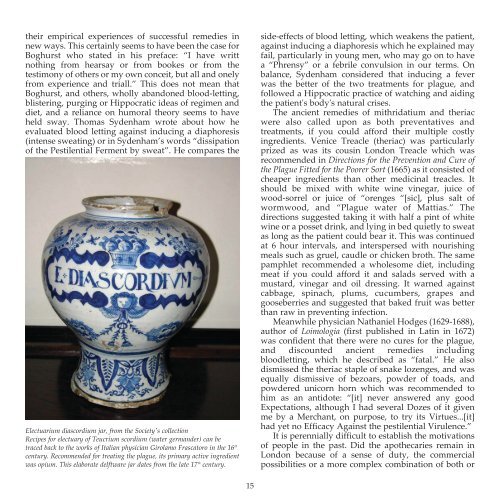

Electuarium diascordium jar, from the Society's collection<br />

Recipes for electuary of Teucrium scordium (water germander) can be<br />

traced back to the works of Italian physician Girolamo Frascatoro in the 16 th<br />

century. Recommended for treating the plague, its primary active ingredient<br />

was opium. This elaborate delftware jar dates from the late 17 th century.<br />

side-effects of blood letting, which weakens the patient,<br />

against inducing a diaphoresis which he explained may<br />

fail, particularly in young men, who may go on to have<br />

a “Phrensy” or a febrile convulsion in our terms. On<br />

balance, Sydenham considered that inducing a fever<br />

was the better of the two treatments for plague, and<br />

followed a Hippocratic practice of watching and aiding<br />

the patient's body's natural crises.<br />

The ancient remedies of mithridatium and theriac<br />

were also called upon as both preventatives and<br />

treatments, if you could afford their multiple costly<br />

ingredients. Venice Treacle (theriac) was particularly<br />

prized as was its cousin London Treacle which was<br />

recommended in Directions for the Prevention and Cure of<br />

the Plague Fitted for the Poorer Sort (1665) as it consisted of<br />

cheaper ingredients than other medicinal treacles. It<br />

should be mixed with white wine vinegar, juice of<br />

wood-sorrel or juice of “orenges “[sic], plus salt of<br />

wormwood, and “Plague water of Mattias.” The<br />

directions suggested taking it with half a pint of white<br />

wine or a posset drink, and lying in bed quietly to sweat<br />

as long as the patient could bear it. This was continued<br />

at 6 hour intervals, and interspersed with nourishing<br />

meals such as gruel, caudle or chicken broth. The same<br />

pamphlet recommended a wholesome diet, including<br />

meat if you could afford it and salads served with a<br />

mustard, vinegar and oil dressing. It warned against<br />

cabbage, spinach, plums, cucumbers, grapes and<br />

gooseberries and suggested that baked fruit was better<br />

than raw in preventing infection.<br />

Meanwhile physician Nathaniel Hodges (1629-1688),<br />

author of Loimologia (first published in Latin in 1672)<br />

was confident that there were no cures for the plague,<br />

and discounted ancient remedies including<br />

bloodletting, which he described as “fatal.” He also<br />

dismissed the theriac staple of snake lozenges, and was<br />

equally dismissive of bezoars, powder of toads, and<br />

powdered unicorn horn which was recommended to<br />

him as an antidote: “[it] never answered any good<br />

Expectations, although I had several Dozes of it given<br />

me by a Merchant, on purpose, to try its Virtues...[it]<br />

had yet no Efficacy Against the pestilential Virulence.”<br />

It is perennially difficult to establish the motivations<br />

of people in the past. Did the apothecaries remain in<br />

London because of a sense of duty, the commercial<br />

possibilities or a more complex combination of both or<br />

15