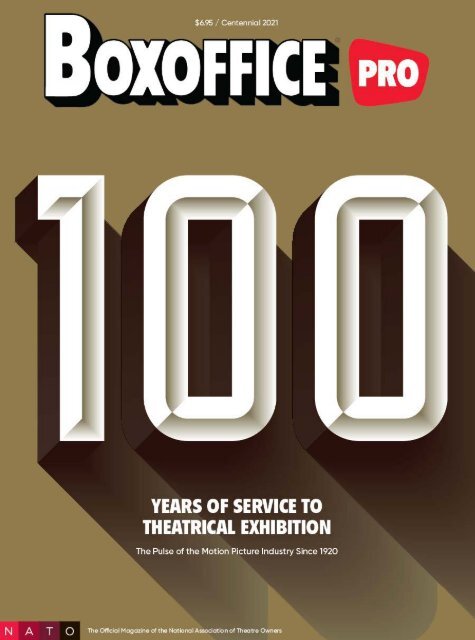

Boxoffice Pro - Centennial Issue

Boxoffice Pro is the official publication of the National Association of Theatre Owners.

Boxoffice Pro is the official publication of the National Association of Theatre Owners.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

50+ Years of Innovation and Linear Lighting Leadership<br />

A Step In The Right Direction<br />

FiberStep by Tivoli combines all the benefits of our Title 24 complaint soft step with<br />

a Fiber Optic light guide on the top row and two visual options for the bottom row.<br />

FiberStep Continuous<br />

Top Row: Fiber Optic “durable” soft glow LED<br />

Bottom Row: LED low brightness TivoTape for a continuous glow<br />

Available Light Color Options<br />

1900K 2700K 3000K 4000K Amber Red Blue<br />

FiberStep Titanium<br />

Top Row: Fiber Optic “durable” soft glow LED<br />

Bottom Row: Patented Titanium LED board with optional on center spacing<br />

ADA<br />

COMPLIANT<br />

www.tivolilighting.com<br />

01_AD-Tivoli.indd 1 23/11/2021 17:26

ai1636522741188_BoxOfficeMagazine_AD_v1-3_20211108_cs6_OP.pdf 2 10/11/2021 1:39 PM<br />

C<br />

M<br />

Y<br />

CM<br />

MY<br />

CY<br />

CMY<br />

K<br />

02_AD-GDC.indd 2 23/11/2021 17:27

03_AD-TSS-Table.indd 3 23/11/2021 17:28

04_AD-MiT.indd 4 23/11/2021 17:28

<strong>Centennial</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

142<br />

Cinematic Enchantment<br />

Disney Puts the Magic in<br />

Magical Realism in the<br />

Animated Musical Encanto<br />

110<br />

Parallel Histories<br />

Parallel Mothers is Pedro<br />

Almodóvar’s Most Explicitly<br />

Political Film Yet. It’s Also<br />

Among His Best.<br />

130<br />

Men Without Women<br />

Ryusuke Hamaguchi<br />

Avoids Getting Lost in<br />

Translation in the Cinematic<br />

Epic Drive My Car<br />

118<br />

California Dreaming<br />

Director Sean Baker on<br />

Red Rocket and the Challenges<br />

Facing Specialty Distribution<br />

136<br />

A Love Story for Jordan<br />

Michael B. Jordan Teams with<br />

Denzel Washington on the True<br />

Account of a Soldier, Husband,<br />

and Devoted Father<br />

05-06_Contents.indd 5 24/11/2021 14:03

CONTENTS<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

ON SCREEN<br />

16<br />

19<br />

22<br />

26<br />

32<br />

42<br />

46<br />

100 Years and Being Counted<br />

Celebrating a Century of<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

Voices from CinemaCon<br />

Reflections from NATO’s Diversity &<br />

Inclusion Scholarship Recipients<br />

Charity Spotlight<br />

A Recap of Industry-Wide Charity<br />

Initiatives<br />

Recovery Year<br />

CinemaCon and CineEurope<br />

Highlight Exhibition’s Post-<br />

Pandemic Concerns and Anxieties<br />

State of the Art House 2021<br />

Leaders of Specialty and Art House<br />

Exhibition on What the Future Holds<br />

Industry Insiders<br />

A Tribute to <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

Executive Editor Kevin Lally in<br />

His Final <strong>Issue</strong><br />

Remembering WOMPI<br />

Celebrating the Legacy of Women of<br />

the Motion Picture Industry<br />

110<br />

118<br />

126<br />

130<br />

Parallel Histories<br />

Parallel Mothers is Pedro Almodóvar’s<br />

Most Explicitly Political Film Yet. It’s<br />

Also Among His Best.<br />

California Dreaming<br />

Director Sean Baker on Red Rocket<br />

and the Challenges Facing Specialty<br />

Distribution<br />

Escape from Afghanistan<br />

Jonas Poher Rasmussen Animates a<br />

Refugee’s Harrowing Journey in the<br />

Acclaimed Documentary Flee<br />

Men Without Women<br />

Ryusuke Hamaguchi Avoids Getting<br />

Lost in Translation in the Cinematic<br />

Epic Drive My Car<br />

136<br />

142<br />

148<br />

151<br />

A Love Story for Jordan<br />

Michael B. Jordan Teams with Denzel<br />

Washington on the True Account of a<br />

Soldier, Husband, and Devoted Father<br />

Cinematic Enchantment<br />

Disney Puts the Magic in Magical<br />

Realism in the Animated Musical<br />

Encanto<br />

Event Cinema Calendar<br />

A Sampling of Event Cinema<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>gramming Hitting the Big<br />

Screen in 2022<br />

Booking Guide<br />

“For me, back then, the cinema<br />

was a parallel universe—the<br />

type of universe I wanted to<br />

live in. The type of universe<br />

you’d only dream about,<br />

one that seemed a lot more<br />

appealing than the harsh<br />

realities of the postwar era.”<br />

Pedro Almodóvar, p. 116<br />

CENTENNIAL<br />

50<br />

54<br />

62<br />

The <strong>Boxoffice</strong> Story!<br />

A Reprint From our 50th Anniversary<br />

<strong>Issue</strong>, Published in 1970, Looking Back<br />

at the Founding of the Publication<br />

The <strong>Boxoffice</strong> Story, Continued<br />

An Institutional History of <strong>Boxoffice</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong> Since Ben Shlyen’s Sale of the<br />

Company<br />

A Century in Exhibition<br />

Documenting 100 Years of Exhibition<br />

History Through the Pages of<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

06 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

05-06_Contents.indd 6 24/11/2021 14:37

ex experience with Q-SYS from QSCww<br />

To the big screen,<br />

and beyond!<br />

CREATE A FULL MULTIPLEX EXPERIENCE WITH Q-SYS FROM QSC<br />

Today’s cinema experience is so much more than movies! And Q-SYS TM is so much more than a<br />

cinema processor. With the Q-SYS Platform you can deliver sound to each theatre and every other<br />

space in the theatre complex where high quality sound is important. You can also monitor and<br />

control every sound system component and many other devices, from anywhere in the building or<br />

remotely from anywhere with a network connection.<br />

qsc.com/cinema<br />

©2021 QSC, LLC all rights reserved. QSC, Q-SYS and the QSC logo are registered trademarks in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and other countries.<br />

07_AD-QSC.indd 7 23/11/2021 17:30

BOXOFFICE MEDIA<br />

CEO<br />

Julien Marcel<br />

SVP Content Strategy<br />

Daniel Loría<br />

Creative Direction<br />

Chris Vickers & Craig Scott<br />

at She Was Only<br />

EVP Chief Administrative Officer<br />

Susan Rich<br />

VP Advertising<br />

Susan Uhrlass<br />

BOXOFFICE PRO<br />

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR<br />

Daniel Loría<br />

DEPUTY EDITOR<br />

Rebecca Pahle<br />

EXECUTIVE EDITOR<br />

Kevin Lally<br />

MANAGING EDITOR<br />

Laura Silver<br />

CHIEF ANALYST<br />

Shawn Robbins<br />

ANALYSTS<br />

Chris Eggertsen<br />

Jesse Rifkin<br />

DATABASE<br />

Diogo Hausen<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Patrick Corcoran<br />

Charles Rivkin<br />

Rolando Rodriguez<br />

Erin Von Hoetzendorff<br />

Vassiliki Malouchou<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

Susan Uhrlass<br />

63 Copps Hill Road<br />

Ridgefield, CT USA 06877<br />

susan@boxoffice.com<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

P.O. Box 215<br />

Congers, NY 10920<br />

833-435-8093 (Toll-Free)<br />

845-450-5212 (Local)<br />

boxoffice@cambeywest.com<br />

CORPORATE<br />

Box Office Media LLC<br />

63 Copps Hill Road<br />

Ridgefield, CT USA 06877<br />

corporate@boxoffice.com<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> has served as the<br />

official publication of the National<br />

Association of Theatre Owners<br />

(NATO) since 2007. As part of this<br />

partnership, <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> is proud to<br />

feature exclusive columns from NATO<br />

while retaining full editorial freedom<br />

throughout its pages. As such, the<br />

views expressed in <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

reflect neither a stance nor an<br />

endorsement from the National<br />

Association of Theatre Owners.<br />

Due to Covid-19, <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

will be adjusting its publishing<br />

schedule. For any further<br />

questions or updates regarding<br />

your subscription, please do not<br />

hesitate to contact our customer<br />

service department at boxoffice@<br />

cambeywest.com.<br />

HISTORICAL<br />

MASTHEAD<br />

PUBLISHERS<br />

Ben Shlyen<br />

(1920–1979)<br />

William J. Vance<br />

(1979–1980)<br />

Robert L. Dietmier<br />

(1980–2005)<br />

Brian Pomerantz & Gidon<br />

Cohen<br />

(2005–2006)<br />

Peter Cane<br />

(2006–2014)<br />

Julien Marcel<br />

(2014–Present)<br />

EDITORS IN CHIEF<br />

Ben Shlyen<br />

(1920–1979)<br />

Charles F. Rouse III<br />

(1979)<br />

Alexander Auerbach<br />

(1980–1984)<br />

Harley W. Lond<br />

(1984–1993)<br />

Ray Greene<br />

(1994–1997)<br />

Kim Williamson<br />

(1998–2006)<br />

Annlee Ellingson<br />

(2007–2008)<br />

Chad Greene<br />

(2008–2009)<br />

Amy Nicholson<br />

(2010–2013)<br />

Daniel Loria<br />

(2014–Present)<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> (ISSN 0006-8527), Volume 157, Number 5, <strong>Centennial</strong> Edition 2021. <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> is<br />

published by Box Office Media LLC, 63 Copps Hill Road, Ridgefield, CT USA 06877.<br />

corporate@boxoffice.com. www.boxoffice.com. Basic annual subscription rate is $75.00. Periodicals<br />

postage paid at Beverly Hills, CA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send all UAA to<br />

CFS. NON-POSTAL AND MILITARY FACILITIES: send address corrections to <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>, P.O. Box 215,<br />

Congers, NY 10920. © Copyright 2021. Box Office Media LLC. All rights reserved. SUBSCRIPTIONS:<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>, P.O. Box 215, Congers, NY 10920 / boxoffice@cambeywest.com. 833-435-8093 (Toll-<br />

Free), 845-450-5212 (Local). Box Office <strong>Pro</strong> is a registered trademark of Box Office Media LLC.<br />

(Jan–Dec 2021) 2,566 / Print - 2,101 / Digital - 465<br />

08 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

08-10_Executive-Letter.indd 8 24/11/2021 17:37

EXECUTIVE LETTER<br />

FORGING A<br />

PATH FORWARD<br />

Two years ago, when we began<br />

preparing for our centennial issue,<br />

we took up the task in the usual way. We<br />

knew we had to be quick and efficient,<br />

and we knew we had to plan everything<br />

in advance in order to stay up to date (the<br />

best one can in a monthly magazine) with<br />

the latest developments in a business<br />

that had just achieved its highest-ever<br />

global earnings. There was enormous<br />

momentum in the industry going into<br />

the holiday season of 2019; it seemed like<br />

the perfect time to celebrate our 100th<br />

anniversary.<br />

What unfolded instead was a series<br />

of events that left a lasting scar on our<br />

personal and professional lives. Here at<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>, the hardships began<br />

with the unfortunate passing of our<br />

longtime creative director, Kenneth<br />

Bacon, in December 2019. Ken was the<br />

longest-serving member of our staff, and<br />

he was, in many ways, the caretaker of this<br />

publication’s history (our archives were<br />

stored in his garage for a period). His wry,<br />

nostalgic Timecode column, which he<br />

compiled from his collection of back issues,<br />

was a reader favorite. Though he is not<br />

with us today, I am sure you will be able to<br />

see his influence throughout this issue.<br />

January 2020 presented another<br />

difficult challenge, with news of a novel<br />

coronavirus spreading in China. None<br />

of us understood what the next months<br />

would bring; even in hindsight, it is<br />

difficult to find words to describe how the<br />

Covid-19 crisis unfolded.<br />

In short, the first quarter of 2020, a<br />

period we had been anticipating as a cause<br />

for celebration, devolved into one of the<br />

most difficult periods in this publication’s<br />

history. We reported as cinemas around<br />

the world voluntarily closed their doors in<br />

March 2020. We were forced, for the first<br />

time in our history, to pause publication of<br />

our monthly magazine.<br />

By the end of the summer, cinemas<br />

had finally reopened, and we were back in<br />

publication. But the past 18 months have<br />

In every crisis there are<br />

opportunities, and revisiting<br />

one’s history is an opportunity<br />

to better prepare for the<br />

future. That is the very spirit<br />

we drew upon in putting<br />

together this issue.<br />

been defined by a prolonged recovery from<br />

the crisis, full of twists, turns, and false<br />

starts. Like the industry we support, we<br />

are still working to get back on our feet.<br />

But that doesn’t mean we aren’t making<br />

progress. I am happy to announce that we<br />

will be publishing a total of eight issues in<br />

2022, three more than the number we ran<br />

in 2021. We are confident that this industry<br />

will show its trademark resiliency in 2022<br />

so that we can print even more issues in<br />

the near future.<br />

What we learned from that incredibly<br />

difficult first quarter of 2020 is the<br />

importance of reacting and adapting to<br />

the world around us. These events could<br />

have destroyed our momentum, derailed<br />

our 100-year legacy. But like the rest of<br />

exhibition, we were committed to forging<br />

a path forward.<br />

The world was in a very different place<br />

in 2020 than it is right now, which is why<br />

we made the difficult decision last year<br />

to postpone our centennial anniversary<br />

issue to December 2021. It didn’t feel<br />

like the right time to look back; we were<br />

focused on the challenges that lay ahead.<br />

Today, however, as we measure the slow<br />

but steady progress we are making in<br />

overcoming this crisis, looking back is<br />

important and necessary—not out of a<br />

sense of nostalgia, but as a way to inform<br />

our understanding of the present. In<br />

every crisis there are opportunities, and<br />

revisiting one’s history is an opportunity<br />

to better prepare for the future.<br />

That is the very spirit we drew upon in<br />

putting together this issue.<br />

It took an extra year to get here, but<br />

we are very proud to share with you the<br />

centennial issue of our publication. We<br />

hope you enjoy reading it as much as we<br />

enjoyed creating it.<br />

Julien Marcel<br />

Chief Executive Officer, The <strong>Boxoffice</strong> Company<br />

Publisher, <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

<strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

09<br />

08-10_Executive-Letter.indd 9 23/11/2021 17:31

EDITOR’S LETTER<br />

PROGRESS IN<br />

THE FACE OF<br />

ADVERSITY<br />

Like the industry we represent, <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

is, I believe, emerging from the pandemic<br />

stronger than ever before—with a renewed<br />

commitment to providing this industry with<br />

the in-depth, vital coverage it has come to<br />

expect from us.<br />

I’ve been both anticipating and<br />

dreading putting this issue together<br />

since I realized, years ago, that I would<br />

be the editor to lead <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s<br />

centennial celebration. The challenge<br />

seemed daunting—100 years of history—<br />

but my concern was assuaged by the fact<br />

that I would be working on it alongside our<br />

creative director, Kenneth Bacon.<br />

As the publication’s longest-serving<br />

employee at the time, Ken was the<br />

unofficial gatekeeper of the magazine’s<br />

history. Since I met him, he had<br />

identified the centennial as his crowning<br />

achievement—the culmination of all his<br />

work at <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>. Ken’s passing, in<br />

December 2019 after a brief illness, on the<br />

day our first issue of 2020 was scheduled<br />

to hit the printer, shook us in a very<br />

deep way. Months later, the onset of the<br />

Covid-19 pandemic further complicated<br />

our approach to the centennial. For the<br />

first time in their existence, movie theaters<br />

around the world were forced to close en<br />

masse, with no indication of when (or if)<br />

they would open their doors once again.<br />

Our staff at <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> has<br />

been in crisis mode since those two<br />

developments, the first an institutional<br />

tragedy, the second an industry-wide<br />

disruption. The pandemic forced us to<br />

take a step back and refocus our attention<br />

away from the centennial so we could<br />

provide our exhibition colleagues with<br />

the best and most extensive coverage<br />

of the ongoing crisis. In April 2020, we<br />

made the difficult decision to suspend the<br />

publication of our magazine until cinemas<br />

reopened at the end of the summer. Since<br />

then, in accordance with the theatrical<br />

market’s slow recovery, we’ve slowed<br />

our publishing frequency to every other<br />

month so we could pivot to breaking-news<br />

coverage on our digital platforms.<br />

Instead of a celebration, 2020 turned<br />

into a year defined by the innovations we<br />

pursued in the face of an existential crisis.<br />

Like the industry we represent, <strong>Boxoffice</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong> is, I believe, emerging from the<br />

pandemic stronger than ever before—with<br />

a renewed commitment to providing this<br />

industry with the in-depth, vital coverage<br />

it has come to expect from us.<br />

The centennial edition of this<br />

magazine, published an entire year<br />

later than we planned, is a testament to<br />

exhibition’s resiliency. It also provided<br />

us with the opportunity to look inward<br />

at how we approach our job. As a trade<br />

magazine, our primary task is to profile<br />

the industry’s leading executives,<br />

trends, concerns, and opportunities. As<br />

journalists, we seek out these stories by<br />

expanding our view of the business to be<br />

as inclusive as possible—whether that<br />

means covering the Netherlands’ microcinemas,<br />

Nigeria’s largest circuits, or, of<br />

course, the North American exhibition<br />

market that is our specialty. We regularly<br />

set our sights outward to enrich the<br />

content in these pages.<br />

Rarely do we have the luxury to<br />

examine our own work and history. Maybe<br />

that’s why, during research for this issue, I<br />

was so charmed by a reprint that appeared<br />

in our 75th anniversary edition: a twopage<br />

spread with pictures of <strong>Boxoffice</strong>’s<br />

entire 1947 roster—from the publisher’s<br />

desk to the mailroom. The story of this<br />

magazine is also the story of the people<br />

who have dedicated their lives to it. A<br />

large part of our focus in this issue is on<br />

the stories of those people and their work<br />

on our publication.<br />

I’d like to thank Alex Auerbach, Peter<br />

Cane, Phil Contrino, Francesca Dinglasan,<br />

Annlee Ellingson, Chad Greene, Ray<br />

Greene, Harley Lond, Julien Marcel, and<br />

Dave Stonehill for spending time with<br />

me to look back on their experiences at<br />

this publication. Their interviews, and<br />

the materials they provided, greatly<br />

informed the institutional history piece<br />

that appears in this issue. Their work is<br />

also documented in Vassilki Malouchou’s<br />

series of articles, “A Century in Exhibition,”<br />

documenting <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s coverage<br />

of the industry through the decades,<br />

which we have republished (for the first<br />

time) in its entirety.<br />

This edition also marks the final issue<br />

in which our colleague, Kevin Lally, will<br />

be part of our masthead. I first became<br />

acquainted with Kevin as a competitor:<br />

He was the longtime editor in chief of<br />

our then-rival Film Journal International.<br />

Today, I feel privileged to know him<br />

as a mentor who helped me navigate<br />

the challenges of this role, and, more<br />

importantly, as a personal friend. Kevin’s<br />

35-year tenure at the helm of FJI is second<br />

only to this magazine’s founder, Ben<br />

Shlyen, as the longest-serving editor of<br />

an exhibition trade magazine in North<br />

America. We are proud to profile Kevin’s<br />

contributions to our industry as part<br />

of <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s own history in our<br />

centennial issue.<br />

Outside of our own story, we’ve put<br />

much work into compiling the industry<br />

coverage that we’re known for. In my<br />

recap of this year’s major exhibition<br />

conventions, you’ll find an assessment of<br />

where exhibition finds itself today—and<br />

where it may be headed in the future. Our<br />

deputy editor, Rebecca Pahle, recaps our<br />

recent webinar panel on the State of the<br />

Art House, providing essential insights<br />

into the specialty market and its potential<br />

evolution. You’ll also find a robust On<br />

Screen section, featuring interviews<br />

with some of today’s most influential<br />

filmmakers (from the multiplex to the art<br />

house) and their upcoming movies.<br />

On behalf of myself, our current staff,<br />

and everyone who has contributed to this<br />

magazine over the past century, thank you<br />

once again for your support.<br />

Daniel Loria<br />

SVP Content Strategy & Editorial Director<br />

BOXOFFICE PRO<br />

10 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

08-10_Executive-Letter.indd 10 23/11/2021 17:31

Experience The New 4K 24,000 Lumen<br />

NC2443ML Digital Cinema Laser <strong>Pro</strong>jector!<br />

Designed for theaters with screens up to 72 ft. wide, NEC's NC2443ML is the latest DCI compliant RB Laser<br />

DLP cinema projector. Delivering precise 4K (4096 x 2160) resolution, 3-D capabilities and high contrast<br />

images, this model is easy to operate, extremely user-friendly and requires minimal maintenance<br />

providing up to 50,000 hours of laser life for unsurpassed TCO.<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>jectors ready to ship!<br />

NC1803ML, NC2003ML, & NP-NC2403ML 2K <strong>Pro</strong>jectors<br />

Coming soon!<br />

NC1843ML & NC2043ML 4K <strong>Pro</strong>jectors<br />

Contact us:<br />

Jeff Kaplan – Sharp/NEC Digital Cinema<br />

Em: jkaplan@sharpnec-displays.com<br />

For more information, visit our website at<br />

www.sharpnecdisplays.us<br />

11_AD-Sharp-NEC.indd 11 23/11/2021 17:33

FOUNDER’S LETTER<br />

THIS IS A<br />

WONDERFUL<br />

BUSINESS!<br />

Nothing goes on for long with<br />

tranquility and quietude. It is<br />

ever a business that keeps one<br />

on his toes and that, in turn, is<br />

what keeps one in the running.<br />

A note from our late founder,<br />

Ben Shlyen, published in the July<br />

20, 1970 issue of <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

BY BEN SHLYEN<br />

Not too far in the past, an industry<br />

executive said to us, “Isn’t this a<br />

wonderful business that can make so many<br />

mistakes and still come out with a profit?”<br />

That question and its obvious answer<br />

have remained with us through the years,<br />

recurring every now and then, especially<br />

when there is occasion to take a doleful<br />

look at happenings that, at the moment,<br />

cast a cloud across the horizon. And,<br />

thinking back over the years – all 50 of<br />

them, to be specific – our mind’s eye<br />

envisages some of the numerous cloudy<br />

periods that the industry has passed<br />

through, each time emerging stronger and<br />

with the outlook brighter than ever before.<br />

We remember a lot of things about<br />

the early days of this industry as it<br />

coursed through the years, from its small<br />

beginnings as a peep-show curiosity to<br />

its peaks of magnitude; from its infancy<br />

to its maturity; from the limited sphere<br />

of its operations to its globe-encircling<br />

strides. None of these steps of progress<br />

was attained or held onto easily, without<br />

some faltering here and there, without<br />

mistakes that were costly or temporary<br />

setbacks. Successes were many, but often<br />

fleeting. Always there was a new obstacle<br />

to overcome. Always it was necessary to<br />

blaze new trails to discover new means<br />

for successful adventures. And always<br />

the need was met with the effort that led<br />

to a new turning point in the road – and<br />

to new horizons.<br />

That is one of the great compensating<br />

factors of this business, in addition to the<br />

profits it may bring. It is adventuresome,<br />

stimulating, and inspiring. Nothing goes<br />

on for long with tranquility and quietude.<br />

It is ever a business that keeps one on his<br />

toes and that, in turn, is what keeps one in<br />

the running.<br />

Not only those who have spent 50 or<br />

more years in this business, but even those<br />

who have been in it only a short time, are<br />

held to it by fascination That is why so<br />

many stick to it through thick and thin,<br />

putting up with trials and tribulations<br />

that they would not long countenance in<br />

any other enterprise. And why so many,<br />

who have found the going in recent times<br />

very hard to bear, are desperately hanging<br />

on. They want to remain a part of this<br />

business as long as possible.<br />

The past decades have been eventful, to<br />

say the least. They serve as foundations to<br />

build on. With some repairing they can be<br />

strengthened, but new building, new ideas<br />

are essential to future industry growth.<br />

What about the future? What course<br />

is there left to take? What new trends will<br />

develop or be developed? Will present<br />

trends, particularly those that have been<br />

unsatisfying or considered inimical to the<br />

industry’s well-being, continue? Will the<br />

old orders and patterns of operations be<br />

restored? Each of these questions has an<br />

answer and, whether or not it is what each<br />

individual or group wants it to be, the<br />

collective industry will continue far into<br />

the future with new marks of progress,<br />

new avenues of profit. Some signs of what<br />

is to come already are beginning to take<br />

shape. Some plans, long in the blueprint<br />

stage, are scheduled for early development<br />

and implementation.<br />

It was with an eye to the future that<br />

the editorial content of this issue was<br />

planned. Looking forward, except for a<br />

glance at highlights of the past for their<br />

interest and whatever guidance value<br />

they might serve, we asked qualified inindustry<br />

executives to tell us what they<br />

could foresee for the industry’s future. All<br />

branches of the business are covered –<br />

production, distribution, exhibition, and<br />

related phases of each. And, throughout<br />

these views, it is significant that a note of<br />

confidence prevails.<br />

Confidence was the key to the success<br />

of the industry’s pioneers and builders<br />

that enabled the motion picture to<br />

grow into the world’s greatest mass<br />

entertainment form. To be sure, many<br />

obstacles were encountered, including<br />

new forms of competition. But, with<br />

courage, foresight, imagination, initiative,<br />

and a venturesome spirit, they built this<br />

business from a handful of storeroom<br />

nickelodeons to thousands of edifices of<br />

beauty and magnitude.<br />

After 50 years of publishing<br />

BOXOFFICE, it is apparent that we<br />

have had an abiding confidence in this<br />

business. That same confidence continues<br />

as we move into a new decade with a<br />

feeling that there are no bounds for this<br />

industry’s opportunities and progress,<br />

especially if the various segments will<br />

extend themselves in working together,<br />

and through increasing evidences of<br />

understanding cooperation.<br />

On this occasion of marking our 50th<br />

anniversary, we take pride in expressing<br />

our appreciation for the congratulatory<br />

messages and good wishes of the friends<br />

the years and our life’s work have<br />

brought us. We are grateful, too, for the<br />

cooperation they have given us along the<br />

way, which has been most heartening and<br />

helpful to our progress.<br />

This is, indeed, a wonderful business –<br />

and it always will be!<br />

12 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

12_Editors-Letter.indd 12 24/11/2021 14:08

THE FEATURES YOU NEED.<br />

THE OPTIONS YOU WANT.<br />

THE COMPANY YOU TRUST.<br />

When it comes to concessions,<br />

it comes from Cretors.<br />

Only Cretors combines five generations of industry leadership with more than<br />

130 years of forward-thinking innovations. Backed by our industrial manufacturing<br />

R&D for global snack food giants, we bring revolutionary products to the<br />

concessions marketplace, time and again. Whether it’s an industry-changing<br />

safety feature, a long-sought-after option or a customizable machine made<br />

for the way you sell anywhere in the world, there’s no limit to our ingenuity.<br />

Made in America, loved world-round!<br />

Contact Shelly Olesen at 847.616.6901 or visit www.cretors.com<br />

13_AD-Creators.indd 13 23/11/2021 17:34

TH<br />

BOXOFFICE PRO<br />

ANNIVERSARY<br />

BLOCKBUSTERS<br />

THE WORLD’S MOST IMMERSIVE PREMIUM EXPERIENCE<br />

WWW.ICETHEATERS.COM<br />

ICE IMMERSIVE TECHNOLOGY I 4K RGB LASER PROJECTION I IMMERSIVE AUDIO I VIP SEAT<br />

14_AD-CGR-ICE.indd 14 23/11/2021 17:34

Congratulations 16 | Charity Spotlight 22 | 2021 in Review 26 | State of the Art House 32<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

“It’s about taking that step coming out of the pandemic in getting<br />

to release models that work for everybody in the industry.”<br />

Recovery Year, p. 26<br />

<strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

15<br />

15_Industry-Opener.indd 15 23/11/2021 17:34

Industry NATO<br />

100 YEARS<br />

AND BEING<br />

COUNTED<br />

Celebrating a Century<br />

of <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

BY ROLANDO RODRIGUEZ &<br />

PATRICK CORCORAN<br />

Congratulations to <strong>Boxoffice</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong> on achieving this significant<br />

milestone! One hundred years of a<br />

singular focus on the business and<br />

art of motion picture exhibition. No<br />

other publication in this space can<br />

claim the longevity or achievements of<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>. Yes, other long-running<br />

entertainment trade publications cover<br />

exhibition, and sometimes cover it well,<br />

but there is nothing like <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>.<br />

The magazine has been re-running<br />

some wonderful pieces on the successes,<br />

failures, and changes in the exhibition<br />

business, and a picture has emerged.<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> goes deep, and its<br />

interest in and coverage of the business<br />

as a business stand out. It tackles the<br />

concerns and challenges that are unique<br />

to exhibition. And just as interesting,<br />

amid all the changes, it acknowledges that<br />

nothing really changes: People want to go<br />

out to the movies, new home technologies<br />

present challenges and opportunities,<br />

movies that are expected to succeed fail,<br />

and movies that come out of nowhere<br />

succeed beyond all expectation.<br />

It was our pleasure and privilege, at<br />

NATO’s Board Meeting in November,<br />

to honor Sumner Redstone and his<br />

formative and lasting impact on NATO<br />

and the exhibition industry. It was<br />

striking, as we dedicated an evening<br />

to him and his legacy, in the presence<br />

of his daughter, Shari Redstone, to see<br />

how much the concerns and interests<br />

of exhibition at NATO’s founding on<br />

January 1, 1966, are the concerns and<br />

interests of exhibition today.<br />

In a memo to the Executive Committee<br />

of the Theatre Owners of America,<br />

proposing the bylaws and constitution of<br />

the new organization to be formed by a<br />

merger with Allied States Association of<br />

Motion Picture Exhibitors (representing<br />

mostly independent exhibitors), Redstone<br />

wrote, “It is designed to attack the<br />

principal problems—shortage of product<br />

and talent. Further, we will spend as<br />

much time as necessary looking for<br />

solutions to the many irritating and<br />

aggravating day-to-day problems facing<br />

exhibition and the industry.”<br />

It is all achingly familiar, and unlike<br />

more general entertainment trades and<br />

consumer publications, <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

brings that perspective to its coverage.<br />

Every technological or consumer<br />

innovation is not the end of exhibition, nor<br />

is the hot topic of the present necessarily a<br />

road map to the future. A photo published<br />

in <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s retrospective of<br />

the 2000s (below, left) brought not just<br />

an awkward photo of then-new NATO<br />

president John Fithian, but a survey of<br />

headlines that could run today.<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> also provides a<br />

unique history and ongoing chronicle<br />

of how, despite the constancy of issues<br />

and concerns, exhibition has evolved and<br />

changed and met new challenges. Take<br />

simultaneous release. <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

covered, with respect and balance, the<br />

2005 experiment of Steven Soderbergh’s<br />

Bubble, in theaters and on VOD at the<br />

same time. There was acrimony and<br />

doomsaying, but <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> provided<br />

space for cooler and more measured<br />

takes from John Fithian, Magnolia and<br />

Landmark Theatres’ Mark Cuban, and<br />

Soderbergh himself. NATO has been able<br />

to maintain a respectful, friendly, and<br />

fruitful relationship with Soderbergh<br />

throughout the years.<br />

NATO, of course, used to publish<br />

its own magazines—NATO News,<br />

followed by In Focus, making for three<br />

publications dedicated to the exhibition<br />

space: <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>, Film Journal<br />

International, and, in the 2000s, In Focus.<br />

This was, from an editorial perspective,<br />

a bounty, but from an advertising<br />

perspective—the perspective of many of<br />

exhibition’s vendors—a burden.<br />

In 2007, following an agreement with<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong>, NATO folded In Focus, and<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> became the official<br />

magazine of the association. NATO would<br />

have dedicated space in the magazine (like<br />

this column), and <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> would<br />

be distributed free of charge to NATO<br />

members, providing benefit to NATO<br />

members and a solid circulation base for<br />

Its interest in and coverage<br />

of the business as a business<br />

stand out. It tackles the<br />

concerns and challenges that<br />

are unique to exhibition.<br />

16 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

16-17_NATO.indd 16 23/11/2021 17:36

Our members will redefine<br />

what the theatrical<br />

experience means. Cinema<br />

is much more than a passive<br />

form of entertainment. It’s<br />

immersive and life changing.<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>. NATO freed financial and<br />

staff resources from publishing a monthly<br />

magazine, and <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> remained<br />

editorially independent. <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong><br />

eventually merged with Film Journal<br />

and stands alone as a unique voice of<br />

exhibition in the media.<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> has continued its strong<br />

internet and social media presence as well.<br />

Its reporters are respected analysts of the<br />

industry and are frequently relied upon<br />

by the trades and consumer publications.<br />

Their sane, historically minded takes<br />

broaden <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s influence and<br />

counter less-informed perspectives.<br />

Throughout the pandemic, <strong>Boxoffice</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong> has innovated and provided tools<br />

to exhibition. Its podcasts and webinars<br />

provided a lifeline of information,<br />

expertise, and an easy way to hear how<br />

other exhibitors around the world have<br />

coped with the crisis. And around the<br />

world is key. As exhibition has expanded<br />

and international theater companies have<br />

become an important engine of world<br />

box office—at least two-thirds in normal<br />

times—<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> has expanded its<br />

reach to meet that new reality.<br />

For the first time this year, at a return to<br />

CinemaCon already recognized as unique,<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> recorded daily podcasts<br />

from the convention to complement its<br />

already extensive coverage. CinemaCon<br />

already frequently calls on <strong>Boxoffice</strong><br />

<strong>Pro</strong> staffers and executives to moderate<br />

panels, knowing they will be handled with<br />

a firm understanding of the industry and<br />

<strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong>’s hallmark fairness.<br />

So here’s to another 100 years and<br />

counting—and being counted—as a vital<br />

asset to the industry. Our thanks and<br />

appreciation for <strong>Boxoffice</strong> <strong>Pro</strong> and its<br />

staff are boundless. Our partnership is one<br />

we treasure, especially, as now, when we<br />

miss our deadlines.<br />

Rolando Rodriguez is NATO Chairman<br />

and Chairman, President & CEO of Marcus<br />

Theatres.<br />

Patrick Corcoran is NATO Vice President &<br />

Chief Communications Officer.<br />

<strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

17<br />

16-17_NATO.indd 17 23/11/2021 17:36

Industry MPA<br />

CHAIRMAN<br />

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER<br />

18 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

18_MPA.indd 18 24/11/2021 14:15

INDUSTRY NATO<br />

WORKING TOWARD<br />

A MORE INCLUSIVE<br />

INDUSTRY<br />

Reflections from NATO’s<br />

2021 Diversity & Inclusion<br />

Scholarship Recipients<br />

BY ERIN VON HOETZENDORFF<br />

Manager of Membership and Global Affairs, NATO<br />

We all remember our first<br />

CinemaCon (or ShoWest). Most<br />

likely, it was dizzying and exhausting, but<br />

it was also enlightening and exciting, a<br />

reminder of why you got into this business<br />

and an incentive to dig into the industry<br />

even more. At CinemaCon 2021, NATO<br />

created the 2021 CinemaCon Diversity<br />

and Inclusion Scholarship to increase<br />

the involvement of underrepresented<br />

individuals and ensure that the industry’s<br />

premier event included the breadth<br />

of people working in exhibition. Five<br />

scholarship recipients attended the event,<br />

from seminars to screenings to meals.<br />

We asked them to reflect on their biggest<br />

takeaway from CinemaCon. Keep reading<br />

to see their reflections, in their own words.<br />

Kelly Allen<br />

General Manager, AMC<br />

Theatres, Austin, Texas<br />

First, let me start by extending a huge<br />

thank you to the D&I Committee and<br />

everyone at NATO for offering the<br />

Diversity and Inclusion Scholarships for<br />

this year’s CinemaCon in Las Vegas. I<br />

believe that CinemaCon is something<br />

everyone in our industry should have the<br />

opportunity to experience. NATO and the<br />

CinemaCon team put on an amazing show,<br />

even with all the challenges that our “new<br />

normal” world has presented in order for<br />

us to operate safely.<br />

As a general manager in the field, I<br />

can oftentimes get tunnel vision and get<br />

wrapped up in the day-to-day insanity<br />

that comes with the territory of operating<br />

a movie theater. Personally, my biggest<br />

takeaway from CinemaCon would be the<br />

continuing importance of my involvement<br />

and education in the industry as a<br />

whole—rather than being solely focused<br />

on the four walls of my building. During<br />

CinemaCon, I was able to meet with<br />

many industry leaders and participate in<br />

valuable discussions about where we are<br />

as an industry and how we can continue<br />

our fight for theatrical exclusivity and<br />

other pertinent issues that affect our<br />

future stability.<br />

My time in Vegas inspired me to<br />

continue being the best leader I can be for<br />

my team and for AMC, and to continue<br />

finding ways to branch out and make<br />

an impact on others. I look forward to<br />

continuing this with my company, as well<br />

as with NATO, as opportunities arise, such<br />

as the Diversity and Inclusion Committee<br />

and more.<br />

Benjamin Smith<br />

General Manager, Movie<br />

Palace Inc., Casper,<br />

Wyoming<br />

I was lucky enough to be selected as a<br />

recipient of the 2021 CinemaCon Diversity<br />

and Inclusion Scholarship. This was my<br />

first CinemaCon experience, and there<br />

was so much to take in, it’s difficult to say<br />

what my biggest takeaway was. One thing<br />

that really resonated with me was all the<br />

creative ideas that were discussed at the<br />

Independent Theatre Owners Committee<br />

meeting. It was great to see how helpful<br />

everyone was and how willing they were<br />

to share their ideas that they implemented<br />

during the shutdowns. Everything from<br />

additional revenue options to employee<br />

happiness and retention was discussed<br />

as a way to help your business succeed<br />

during these difficult times. The great part<br />

for me was that these were all from people<br />

running similar-size operations as I do, so<br />

I was really able to relate to the struggle<br />

and implementation of the discussions.<br />

I attended many other meetings<br />

that really helped me see how the<br />

industry works as a whole, not just<br />

from the exhibition side. Having a deep<br />

understanding of the things you are<br />

immersed in is, I think, a critical part of<br />

being efficient and making decisions. A<br />

mechanic can’t make a decision about<br />

what part to replace on a car without a<br />

thorough understanding of how all the<br />

parts work together. While that may be a<br />

bit of an exaggerated example, it leads me<br />

to my point: I learned how all different<br />

parts of this wonderfully unique industry<br />

work together, more or less, to benefit<br />

each other. While I may not have one<br />

specific implementation to offer, I gained<br />

a much deeper understanding of the<br />

industry, which has helped me become a<br />

better leader and manager.<br />

<strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

19<br />

19-20_NATO-CinemaCon.indd 19 24/11/2021 14:16

INDUSTRY NATO<br />

Constance Camat<br />

Marketing Manager, Tango<br />

Theatres, Dededo, Guam<br />

Coming from an insular area, I found<br />

CinemaCon 2021 to be an eye-opening<br />

experience. I was surrounded by other<br />

individuals who are as passionate, or<br />

maybe even more passionate, as I am<br />

about this industry. The pandemic has<br />

hit every industry, but none as severely as<br />

the movie industry. Yet from closures to<br />

simultaneous on-demand and theatrical<br />

release dates, movie theaters still stand<br />

strong and move together as an industry<br />

like never before. Being able to network<br />

with others going through the same<br />

struggles has helped our location find<br />

ways to continue to survive.<br />

Tango Theatres is the place on our<br />

island for Filipino films. Since reopening,<br />

it has been a struggle to reopen that<br />

market. Thankfully, we were able to<br />

broaden our foreign films by adding<br />

Japanese anime and K-pop concert<br />

films. We have been able to work with<br />

our community to find other uses for our<br />

auditoriums. From book signings to job<br />

fairs, we are able to help the community<br />

have a sense of normalcy. Our location<br />

has begun to explore the possibilities<br />

of offering our auditoriums for karaoke<br />

and gaming, as it has done well for other<br />

theater owners. I look forward to returning<br />

to CinemaCon to see what our industry<br />

has yet to offer our fellow moviegoers.<br />

Logan Crow<br />

Executive Director/<br />

Founder, The Frida Cinema,<br />

Santa Ana, California<br />

Easily my biggest takeaway from<br />

attending CinemaCon is a sense that,<br />

big or small, we’re all in this together.<br />

Prior to attending, I’d admittedly been<br />

under the assumption that the problems<br />

faced by community, nonprofit art<br />

house cinemas like The Frida Cinema<br />

wouldn’t be relevant to the operations<br />

of larger commercial cinemas, and<br />

therefore I’ve stuck to networking with<br />

my community of fellow art houses for<br />

perspectives and guidance. Throughout<br />

the conference, I was fortunate to meet<br />

and have great conversations with so<br />

many representatives of cinemas, from<br />

single-screen to multiplex, single-venue<br />

to mega-chain, and the general gist of<br />

every conversation centered on the same<br />

themes: How do we best serve and reflect<br />

the varying interests of our communities;<br />

how do we reopen our doors and<br />

continue to provide entertainment to our<br />

communities while navigating the varying<br />

perspectives on Covid-19 precautions<br />

and restrictions; how do we maintain<br />

staff morale during these difficult times;<br />

and perhaps most universally, at a time<br />

when streaming platforms are growing<br />

exponentially in popularity, how do we<br />

best advocate—to both our customers and<br />

our distributors—for the time-honored<br />

tradition of going out to the movies?<br />

Those conversations have continued in<br />

the months since CinemaCon, and these<br />

new relationships, and the perspectives<br />

we have shared, have been invaluable.<br />

Movie theaters big and small, we truly are<br />

in this together. Long live the cinematic<br />

experience!<br />

Richard Martin<br />

<strong>Pro</strong>gramming Manager,<br />

Plaza Theatre, Atlanta<br />

After a year of extreme speculation in<br />

theatrical exhibition and the evolution<br />

of distribution, CinemaCon 2021 was one<br />

of the most reassuring experiences I’ve<br />

had in the past year. Seeing our industry<br />

endure and continue to weather the storm<br />

of a global pandemic to continue our<br />

long-cherished tradition of entertainment<br />

inspired me deeply. To see the overall<br />

positivity around our commitment to<br />

the theatrical experience, and to also see<br />

the continued response to customers<br />

returning to the big screen, proves<br />

that one of the main rallying cries of<br />

CinemaCon is true: “The Big Screen Is<br />

Back.” Getting the opportunity to truly<br />

feel like part of the industry and to get a<br />

glimpse of the future of our industry and<br />

a personal introduction to the industry’s<br />

warmth and interesting idiosyncrasies<br />

was one of the greatest moments in<br />

my career. The people, the parties, the<br />

constant interaction and hearing many<br />

differing opinions about how the industry<br />

should go into the future—there was<br />

nothing but a wealth of hope out there in<br />

our industry. The landscape of theatrical<br />

exhibition is still foggy, but in the end,<br />

it will never truly die, and CinemaCon<br />

was proof of that. Seeing the exhibition<br />

industry move forward will be quite the<br />

interesting adventure, but one thing is<br />

certain, there will never be anything like<br />

going to the movies, and we’re here to<br />

make sure that that stays true.<br />

20 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

19-20_NATO-CinemaCon.indd 20 23/11/2021 17:38

We want to thank the entire cast and crew who give our kids the chance to feel like stars.<br />

To our donors, you make dreams come true. You change lives for the better. You help<br />

overcome the stigma and isolation faced by children living with special needs.<br />

Learn more or become a donor at varietytexas.org<br />

21_AD-Variety.indd 21 23/11/2021 17:38

INDUSTRY CHARITY SPOTLIGHT<br />

CHARITY<br />

SPOTLIGHT<br />

Know of a recent or upcoming event<br />

that should be included in Charity<br />

Spotlight? Send us the details at<br />

numbers@boxoffice.com.<br />

VARIETY – THE<br />

CHILDREN’S CHARITY<br />

RINGS IN THE HOLIDAYS<br />

Variety of Detroit<br />

On Friday, October 22, 2021, Variety of<br />

Detroit hosted Hearts & Stars at the<br />

Townsend Hotel, honoring Lois Shaevsky,<br />

former president of Variety of Detroit.<br />

Shaevsky (above, with Variety of Detroit<br />

co-chairs Laurie Fischgrund and Rhonda<br />

Sabatini and president David King) was<br />

honored with the Variety Heart Award<br />

for her dedication to Variety of Detroit for<br />

35 years.<br />

This year marks Variety of Detroit’s 14thannual<br />

Holiday Adopt-a-Child. Donors<br />

“adopt” one (or more!) children and receive<br />

a wish list of ideas and sizes. Sponsors<br />

shop at their convenience, then bring the<br />

unwrapped gifts to Santa’s Workshop on<br />

December 4—where they wrap gifts and<br />

get into the holiday spirit. Variety of Detroit<br />

provides the wrapping paper, food, and fun!<br />

Variety of Wisconsin<br />

Variety of Wisconsin families enjoyed a<br />

beautiful day at the Haunted Mansion<br />

Maze at FrankenStein’s Fest at Stein’s<br />

Garden and Home. Stein’s is a great<br />

partner to Variety and offers this inclusive,<br />

fun trick-or-treat and fall experience,<br />

complete with a pumpkin patch, at its<br />

Brookfield, Wisconsin store.<br />

Variety of Illinois<br />

Variety of Illinois kids had a fangtastic<br />

Halloween, stopping by a trunk-or-treat<br />

monster mobile for candy, glow toys, and<br />

a map of 30 Halloween yard displays in<br />

Chicago’s suburbs. This drive-yourself<br />

tour provided a fun and safe alternative<br />

to traditional trick-or-treating for<br />

immunocompromised children with<br />

disabilities.<br />

SANTIKOS GETS INTO THE<br />

GIVING SPIRIT<br />

Throughout the month of November,<br />

Santikos Entertainment hosted their<br />

annual toy drive, spreading the holiday<br />

spirit across their community. Every<br />

customer that donated a gift received<br />

a 30-minute arcade game card and two<br />

Santikos coupons, free of charge.<br />

SMG CONNECTS WITH<br />

THEIR COMMUNITIES<br />

Studio Movie Grill’s Sunset Walk location<br />

in Orlando-Kissimmee, Florida, donated<br />

two theaters (a total of 250 seats) to<br />

Sunset Walk’s inaugural Special Olympics<br />

5K, which was run around the Sunset<br />

Walk shopping center on October 30 and<br />

raised over $92,000 for Special Olympics<br />

Florida. Wristbands were given to those<br />

who finished the race, allowing them to<br />

come in and watch The Addams Family<br />

as an extension of SMG’s Special Needs<br />

Screenings program.<br />

Studio Movie Grill’s Rocklin, California<br />

location held a fundraising event for the<br />

Firefighters Burn Institute, while the<br />

CityCentre location in Houston, Texas,<br />

hosted a premiere screening of the<br />

documentary Delivering Hope to benefit<br />

Snowdrop Foundation, which funds<br />

childhood cancer research and college<br />

scholarships for pediatric cancer patients.<br />

22 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

22-24_Charity-Spotlight.indd 22 23/11/2021 17:39

MEGAPLEX THEATRES<br />

FULFILLS A CHARITABLE<br />

LEGACY<br />

Utah-based Larry H. Miller Megaplex<br />

Theatres celebrates the season of giving<br />

by supporting a variety of local charities<br />

and community organizations. As part of<br />

the Larry H. Miller Group of Companies,<br />

Megaplex Theatres operates to benefit<br />

and serve the community through Larry<br />

H. Miller Charities—a program that is<br />

funded through voluntary donations<br />

made by Megaplex Theatres employees<br />

and matched by the Miller family. Funds<br />

are used to support people and programs<br />

in the communities where Megaplex<br />

employees live and work. A special focus<br />

is placed on supporting organizations that<br />

serve health and education goals. Recent<br />

beneficiaries include Boys and Girls Clubs,<br />

Primary Children’s Hospital, Sub for Santa,<br />

United Way, Big Brothers and Big Sisters<br />

of Utah, Toys for Tots, and many more. In<br />

addition, Megaplex Theatres honors the<br />

company’s late founder, Larry H. Miller,<br />

with an annual Day of Service in which<br />

Megaplex employees roll up their sleeves<br />

to clean up parks, spruce up community<br />

shelters, assemble hygiene kits, and host<br />

food and clothing drives to help those<br />

in need. Every day, Megaplex employees<br />

are encouraged to embody the words of<br />

company founder Larry H. Miller: “Go out<br />

into the world and do good until there is<br />

too much good in the world.”<br />

“Go out into the world and do<br />

good until there is too much<br />

good in the world.”<br />

CANADIAN PICTURE<br />

PIONEERS RETURNS TO<br />

IN-PERSON EVENTS<br />

The Canadian Picture Pioneers were<br />

determined to host in-person events<br />

in the summer of 2021 to get industry<br />

members together, as long as it was safe<br />

to do so. In August, the CPP celebrated<br />

the return of moviegoing by hosting a<br />

night out at a Premier Theatres Drive-In<br />

cinema in Toronto. Later that month,<br />

CPP hosted their annual Summer Golf<br />

Event (above). Although health and safety<br />

protocols meant that they had to change<br />

some elements of how they’ve hosted<br />

the tournament in the past, they were<br />

still able to get more than 100 golfers out<br />

to spend some time together and play a<br />

round. With the help of their members<br />

and loyal corporate partners, CPP raised<br />

over $15,000.<br />

HAPPY HOLIDAYS FROM<br />

THE MOTION PICTURE<br />

CLUB<br />

The Motion Picture Club got into the spirit<br />

of the season with their annual holiday<br />

party, hosted on Thursday, December 16,<br />

at Ruth’s Chris Steak House in Manhattan.<br />

Events such as the holiday party help MPC<br />

make substantial contributions to Variety<br />

– the Children’s Charity, the Will Rogers<br />

Memorial Fund, the Motion Picture<br />

Pioneers, Rising Ground, and the Ronald<br />

McDonald House.<br />

<strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

23<br />

22-24_Charity-Spotlight.indd 23 23/11/2021 17:39

INDUSTRY CHARITY SPOTLIGHT<br />

“The last two years have been<br />

especially challenging for those in<br />

our community struggling to feed<br />

their families.”<br />

CINERGY ENTERTAINMENT<br />

GROUP HOSTS ANNUAL<br />

THANKSGIVING FOOD<br />

DRIVE<br />

Dallas-based Cinergy Entertainment<br />

Group once again hosted their annual<br />

Thanksgiving food drive, benefiting<br />

local food banks that serve the more<br />

than 2 million households across Texas<br />

and Oklahoma that are in severe need of<br />

their next meal. Cinergy offered guests<br />

their choice of a $5 game card or a free<br />

popcorn in exchange for two canned food<br />

items, dropped off at any Cinergy location<br />

between November 4 and November 28.<br />

Over the years, Cinergy has donated a total<br />

of five tons of food to local food banks.<br />

“The last two years have been especially<br />

challenging for those in our community<br />

struggling to feed their families. With<br />

Cinergy, we will be able to provide<br />

food to so many people in need,” said<br />

James Marcum, commissioning pastor<br />

of StoneWater Church, adding: “We<br />

are excited to work together to make a<br />

difference in our community.”<br />

“We are grateful to have the opportunity<br />

to help fight hunger in our communities<br />

and make the holidays a little better for<br />

the struggling families around us,” said<br />

Cinergy’s V.P. of marketing Traci Hoey.<br />

“This year, we hope to provide over 5,000<br />

meals for people in need throughout Texas<br />

and Oklahoma.”<br />

WILL ROGERS RENEWS<br />

ITS COMMITMENT TO<br />

PULMONARY HEALTH IN<br />

THE AGE OF COVID<br />

While the significance of pulmonary<br />

health and rehabilitation is not new to the<br />

Will Rogers Institute, the global health<br />

pandemic has solidified its importance in<br />

the minds of people across the world. To<br />

date, the Will Rogers Institute has funded<br />

$48,740,177 in research grants, training<br />

fellowships, and special projects in the<br />

pulmonary sector.<br />

What began as a training program for<br />

medical research during the 1950s and ’60s<br />

at the Will Rogers Hospital in upstate New<br />

York lives on in the present day through<br />

the work of the Will Rogers Institute.<br />

Today, the Will Rogers Institute funds the<br />

Will Rogers Institute Pulmonary Research<br />

Center at Keck School of Medicine of USC,<br />

as well as six fellowships across the United<br />

States. The Institute is making strides<br />

every day in understanding, treating, and<br />

curing pulmonary diseases and disorders,<br />

including Covid-19.<br />

While rooted in pulmonary health<br />

from the beginning, Will Rogers Institute<br />

Fellowship hospitals have shifted their<br />

focus over the last 18 months to research<br />

the effects of Covid-19, particularly “longhaul”<br />

Covid-19.<br />

As of November 2, 2021, more than<br />

46 million cases of Covid-19 had been<br />

reported to the CDC, along with 745,000<br />

deaths. Many Covid patients recover and<br />

experience no lingering health problems<br />

after the initial infection. However,<br />

studies estimate that between 10 and 30<br />

percent of Covid-19 patients experience<br />

symptoms that persist six months after<br />

the acute infection. Often referred to as<br />

“long Covid,” these lingering symptoms<br />

include fatigue, brain fog, shortness of<br />

breath, and severe headaches. This means<br />

that nearly 14 million people are likely<br />

affected by long Covid.<br />

According to Edward D. Crandall,<br />

PhD, M.D., director, Will Rogers Institute<br />

Pulmonary Research Center at USC, “The<br />

idea to study and prepare informational<br />

materials about long Covid is a worthwhile<br />

undertaking that can fit within the WRI<br />

educational mission. While it’s unclear<br />

how large a problem it will turn out to<br />

be as a sustained health threat, long<br />

Covid needs to be studied and especially<br />

managed as a public and population<br />

health risk.”<br />

Support of the Will Rogers Institute<br />

during this time has the potential to<br />

impact millions of people suffering from<br />

debilitating effects of long Covid and other<br />

pulmonary-related illnesses. Visit www.<br />

wrinstitute.org/donate to make a donation.<br />

24 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

22-24_Charity-Spotlight.indd 24 23/11/2021 17:39

25_AD-Will-Rogers.indd 25 23/11/2021 17:39

Industry 2021: YEAR IN REVIEW<br />

RECOVERY<br />

YEAR<br />

CinemaCon and CineEurope<br />

Highlight Exhibition’s Post-<br />

Pandemic Concerns and<br />

Anxieties<br />

BY DANIEL LORIA<br />

There was an anxious anticipation<br />

leading up to CinemaCon 2021, held<br />

in August at its usual site, Caesars Palace<br />

in Las Vegas. For one, Covid-19 cases were<br />

surging due to the Delta variant. Other<br />

large-scale conventions had rescheduled<br />

or canceled their 2021 editions entirely.<br />

Secondly, there were still concerns and<br />

questions about the potential impact<br />

of the Delta variant on the cinema<br />

industry. After enduring 18 months of<br />

closures, operational restrictions, staffing<br />

challenges, and release delays, exhibitors<br />

found themselves at a difficult crossroads.<br />

CinemaCon 2021 had the potential to<br />

represent the start of the moviegoing<br />

recovery—it would no longer be the<br />

victory lap many industry insiders had<br />

hoped for—but the industry still faced<br />

serious questions about the months ahead.<br />

In addition to the general sense of<br />

unease, CinemaCon 2021 was further<br />

impacted by international travel<br />

restrictions and the pandemic’s toll on<br />

cinema vendors and suppliers. It was<br />

clear from the start that CinemaCon 2021<br />

was going to be a smaller affair than in<br />

years past. Nevertheless, the National<br />

Association of Theatre Owners (NATO) felt<br />

it was crucial to mount the event despite<br />

these challenges.<br />

“There was never a doubt that we were<br />

going to hold it,” said NATO’s John Fithian<br />

during a live taping of Cinionic’s podcast,<br />

The Insiders, at CinemaCon, after being<br />

asked if the association considered bowing<br />

to the pressure of canceling the event for a<br />

second consecutive year. “We knew there<br />

were going to be challenges. We knew<br />

that some, for their individual reasons of<br />

risk calculation, didn’t want to come. And<br />

that’s fine. We knew that many people still<br />

wanted to come and wanted to get back to<br />

doing business together with their partners.”<br />

This year’s CinemaCon, along with<br />

its European counterpart, CineEurope,<br />

which went ahead in October, reflected<br />

the back-to-business resolve in Fithian’s<br />

words. Yet the sector was still reeling from<br />

the financial devastation of the pandemic.<br />

Global box office revenue dropped by 72<br />

percent in 2020 from 2019’s $42 billion<br />

record-setting year. North America<br />

suffered an 80 percent decline in annual<br />

box office, breaking its yearslong streak<br />

of $11 billion per year and relinquishing<br />

its status as the world’s highest-earning<br />

market to China.<br />

26 <strong>Centennial</strong> 2021<br />

26-31_Recovery-Year.indd 26 23/11/2021 17:40

In Europe, where admissions had<br />

reached their highest level since 2004—<br />

growing by 34 percent since the year<br />

2000—UNIC territories suffered a 68<br />

percent drop in attendance over 2020.<br />

“We had a small epidemic in 2009 with<br />

the H1N1 flu in Mexico. The government<br />

shut down everything for a week. It took<br />

us five weeks to recover and we thought<br />

it was devastating,” said Cinépolis<br />

CEO Alejandro Ramírez Magaña at a<br />

CinemaCon panel. “When this began,<br />

that was our only reference point to an<br />

epidemic. We thought this could be a oneweek<br />

shutdown or a 10-week shutdown<br />

followed by 12 weeks of recovery. We never<br />

in our wildest dreams imagined that a<br />

year and a half later we would still have<br />

countries that were fully closed.”<br />

The disruption caused by the pandemic<br />

has been acutely felt by the multinational<br />

circuits, which represent the highest<br />

screen counts. Mooky Greidinger, CEO<br />

of Cineworld, the world’s second-largest<br />

exhibitor and parent company of Regal<br />

Cinemas, spoke about those challenges<br />

at a CinemaCon panel. “We operate in<br />

10 countries and received different rules<br />

from every government,” he said. “One<br />

prime minister thinks the best thing is<br />

for kids to not be allowed at the movies.<br />

Another one thinks we need to keep five<br />

seats between transactions. The third<br />

one thinks we should not sell popcorn.<br />

It’s crazy. And you’re dealing with these<br />

changes across territories on a daily basis.<br />

Now it’s quieted down a little bit, where<br />

we are almost with no restrictions in most<br />

countries, but at its peak it was a disaster<br />

because there were changes every day.”<br />

Regal remedied those challenges<br />

by closing all its locations worldwide in<br />

October 2020, citing varied operating<br />

restrictions across territories and the<br />

volatility of studios’ theatrical release<br />

schedules. For Cinépolis, Ramirez Magaña<br />

noted his circuit conducted a market-bymarket<br />

analysis when deciding where to<br />

keep theaters closed and when to reopen.<br />

“We don’t call it a breakeven analysis, but a<br />

loss-even analysis. How do you lose less:<br />

open or closed? Because you’re going to lose<br />

in both instances, it’s all about how you<br />

minimize burning cash,” he said.<br />

The pace of reopening cinemas<br />

increased through Q3 2021, following the<br />

wider access to vaccines and a peak of the<br />

highly contagious Covid-19 Delta variant.<br />

Another major factor was the stabilization<br />

of the theatrical release schedule, with<br />

studios’ increased confidence in releasing<br />

major titles—albeit under significantly<br />

different business terms. Theatrical<br />

exclusivity windows were once again at<br />

the forefront of discussions at CinemaCon<br />

and CineEurope in 2021. The contentious<br />

topic took on an increased importance<br />

following the experimentations in studios’<br />

release strategies during the pandemic.<br />

Addressing the topic on Cinionic’s<br />

podcast, The Insiders, Fithian distanced<br />

himself and NATO from discussions<br />

about the duration of windows while<br />

expressing his general support for a<br />

period of theatrical exclusivity. “People<br />

talk about the window as if there’s only<br />

one. There are multiple windows, and<br />

each studio has a different perspective<br />

on what is important in those multiple<br />

windows,” he said. “Our members are<br />

working through all those issues with the<br />

studios now, and we’re encouraged by<br />

it. Windows coming out of the pandemic<br />

won’t be what they were before the<br />

pandemic. They’re not going to be what<br />

they were during the pandemic, either.<br />

It’s about taking that step coming out of<br />

the pandemic in getting to release models<br />

that work for everybody in the industry.”<br />

“I think decisions like day-and-date<br />

have been made because of Covid, and<br />

there have been adjustments to everyone’s<br />

benefit. Going forward, I think the<br />

long-term solution is a proper exclusive<br />

theatrical window,” said Chris Aronson,<br />

president of domestic distribution at<br />

Paramount Pictures, during a CinemaCon<br />

roundtable. “A lot of this experimentation<br />

that has been going on with windows<br />

was eventually going to happen. It’s been<br />

accelerated because of the pandemic. But<br />

I think [the notion of] a proper theatrical<br />

window holds. It’s what gets people<br />

talking about the movies. Finding the<br />

“Once you get people<br />

coming to see movies,<br />

they’re exposed to trailers,<br />

they’re exposed to marketing<br />

materials, and they discover<br />

it’s actually a lot of fun going<br />

back to the movies.”<br />

proper window—we may still be trying to<br />

figure that out.”<br />

For major circuits like Cinemark, the<br />

third-largest chain in North America,<br />

the length of that window appears to be<br />

a 45-day exclusive run for major titles.<br />

“Sometimes the windows will be a little<br />

shorter than 45 days, if it’s a smaller or<br />

modest-size movie. But for the big movies,<br />

that’s really what we’re looking for,” said<br />

Cinemark CEO Mark Zoradi. “We use the<br />

term ‘dynamic window’ as another way<br />

of saying ‘flexible window.’ Because with<br />

the bigger blockbuster movies, content<br />

providers want a longer window—it’s<br />

going to be to their advantage to get as<br />

much of that box office as possible. It<br />

starts with theatrical; it helps create the<br />

franchise and ‘eventizes’ the movie. You<br />

get your highest per-cap anywhere in<br />

the [distribution] chain with [exclusive]<br />

theatrical distribution.”<br />

Fithian says a dynamic exclusivity<br />

window can help more independent and<br />

midsize movies reach a wider number of<br />

screens, particularly with the expiration<br />

of the binding virtual print fee model.<br />

Under that structure, smaller distributors<br />

found themselves priced out of exhibitors’<br />

agreements with the studios that helped<br />

finance the transition to digital projection.<br />

“With VPF deals coming to an end, the<br />

barrier to entry for smaller films has gone<br />

down tremendously. When you combine<br />

more dynamic windowing capabilities<br />

with the end of the VPFs, we expect a<br />

resurgence of small art films and midbudget<br />

films in cinemas,” he said.<br />

A diverse slate of films will be crucial<br />

for cinemas’ recovery from the pandemic.<br />

The assumption that one film alone can<br />

spur a comeback—as the industry learned<br />

with the release of Christopher Nolan’s<br />

Tenet during the pandemic—places undue<br />

expectations on the film in question and<br />

fails to address the frequency of attendance<br />

necessary for the theatrical model to<br />