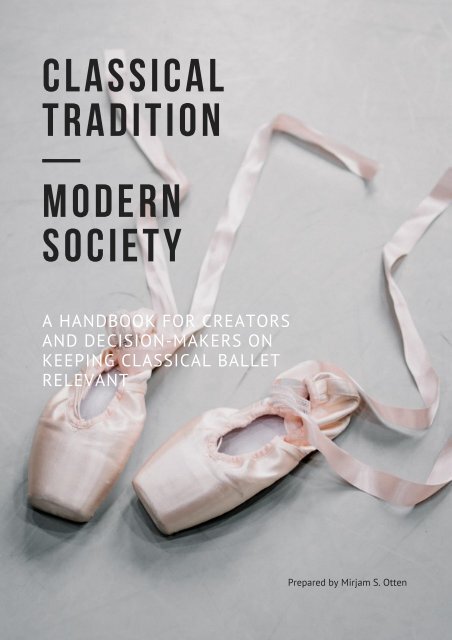

Tanzrecherche NRW: Classical Tradition / Modern Society by Mirjam Otten

A handbook for creators and decision-makers on keeping classical ballet relevant

A handbook for creators and decision-makers on keeping classical ballet relevant

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

C L A S S I C A L<br />

T R A D I T I O N<br />

—<br />

M O D E R N<br />

S O C I E T Y<br />

A HANDBOOK FOR CREATORS<br />

AND DECISION-MAKERS ON<br />

KEEPING CLASSICAL BALLET<br />

RELEVANT<br />

Prepared <strong>by</strong> <strong>Mirjam</strong> S. <strong>Otten</strong>

Credits<br />

<strong>Mirjam</strong> S. <strong>Otten</strong>, BA AKC<br />

In der <strong>Tanzrecherche</strong> #40 des <strong>NRW</strong> Kultursekretariat<br />

E-mail: mirjam.s.otten(at)gmail.com<br />

https://www.mirjamotten.net/<br />

A grant from <strong>NRW</strong> KULTURsekretariat — funded <strong>by</strong> the<br />

Ministry of Culture and Sciences of the Federal State<br />

North Rhine-Westphalia.<br />

© <strong>Mirjam</strong> S. <strong>Otten</strong>, BA AKC 2022<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 00

Contents<br />

SECTION I<br />

Background<br />

Introduction<br />

SECTION II<br />

ELEMENTS OF RELEVANCE<br />

The Nature of Ballet<br />

Social Context<br />

Relations<br />

Programme &<br />

Productions<br />

03<br />

04<br />

10<br />

15<br />

17<br />

24<br />

28<br />

38<br />

Objectives & Methodology<br />

Interviewees<br />

Heritage, Appropriation & Evolution<br />

Criticism and Relevance Today<br />

Heritage Preservation<br />

A Word on Contemporary Dance<br />

Government<br />

Value System<br />

Performance Art<br />

Workmanship<br />

Technique<br />

Status<br />

Social Developments<br />

Current Affairs<br />

Technological Developments<br />

Cross-Sector Relations<br />

International Exchange<br />

Public Relations & Media<br />

Audience-Building<br />

Education<br />

Outreach & Engagement<br />

Public Participation<br />

Programming<br />

Re-working Heritage Pieces<br />

New Commissions<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 01

Good practice<br />

Production<br />

Characteristics<br />

People<br />

Industry<br />

Characteristics<br />

44<br />

51<br />

63<br />

68<br />

Re-enactment<br />

The Artistic Process<br />

Training<br />

Communication<br />

Artistsic Agency<br />

Dancing<br />

Insights<br />

Quality<br />

Scale<br />

Contents<br />

Storytelling<br />

Emotional Experience<br />

Mood<br />

Integrated Production Elements<br />

Venue<br />

‘Show experience’<br />

Format<br />

Choreographic Talent<br />

Collaborators<br />

Directors & Leadership<br />

Boards of Directos<br />

Career Pathways<br />

Institutions<br />

Psychology<br />

Equality & Diversity<br />

SECTION III 74<br />

Discussion<br />

75<br />

Challenges<br />

About the Author<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Bibliography<br />

Appendix<br />

82<br />

A: Further Reading<br />

B: Interview Questions<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 02

SECTION I<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 03

CONTEXT<br />

Background<br />

This research into the continued relevance of classical ballet<br />

emerged in the context of the <strong>NRW</strong> Kultursekretariat<br />

(<strong>NRW</strong>KS) programme ‘Dance Research <strong>NRW</strong>’. The <strong>NRW</strong>KS is<br />

the German Federal Country North Rhine- Westphalia's Office<br />

of Culture, a public-law initiative of theater- and orchestrabearing<br />

cities and one regional association in the state.<br />

Working closely with the Ministry of Culture, it is committed<br />

to promoting intercultural projects and cultural exchange.<br />

‘Dance Research <strong>NRW</strong>’ is a scholarship programme that aims<br />

to enable artists and creatives in the dance sector to<br />

undertake independent research with special regional,<br />

political, cultural, social or scientific references.<br />

<strong>Mirjam</strong> <strong>Otten</strong>’s Dance Research #40, titled ‘<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

/ <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong>’ explores how the classical dance heritage<br />

can maintain continued social relevance. By learning how<br />

ballet companies, leaders and creators handle decisionmaking<br />

around the classical heritage and new impulses, it<br />

wants to gain and present insights into different ways of<br />

making the classical movement, style and stories accessible<br />

to the modern viewer.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 04

METHODOLOGY<br />

Primary data collection was preceeded <strong>by</strong> a profound review of the literature.<br />

Search terms included permutations of ‘dance’, ‘ballet’, ‘relevance’, ‘heritage’,<br />

‘modernisation’, ‘preservation’ and ‘culture’. A large array of resources was found, 22<br />

of which were reviewed in-depth (see Bibliography). Further resources are available<br />

(see Appendix A).<br />

In order to understand practical tools and considerations around relevance within<br />

the current dance industry, a range of interviews was then conducted with directors,<br />

choreographers, producers and leaders of the international dance scene. Although<br />

the literature often suggests that it is only the Artistic Director who holds power to<br />

determine a company’s relevance <strong>by</strong> making decisions around repertoire, casting<br />

and sometimes even choreography itself (Schnell, 2014), a decision was made to<br />

include creative staff of varying positions so as to reflect a more thorough and<br />

profound view of current industry dynamics. Interviewees were asked to participate<br />

on a voluntary basis. Out of 19 approached contacts, 11 agreed to participate and 7<br />

of them completed the interview process. Interviews were eiter held via Microsoft<br />

Teams or in person and consisted of 9 to 12 questions (see Appendix B). Interviews<br />

lasted between 30 minutes to 1 hour and were conducted in January and February<br />

2022.<br />

TERMINOLOGY<br />

The concept ‘relevance’ takes on different meanings in interaction with different<br />

target groups. As Dominic Antonucci pointed out in his interview, ‘something that<br />

might be relevant for arts council funding might not be relevant to the headlines of<br />

the press, which in terms might not be relevant to the audience.’ For the purpose of<br />

this research and report, ‘relevance’ will refer to the ability to connect with an<br />

audience.<br />

When talking about classical dance heritage, interviewees were encouraged to refer<br />

to all elements of this heritage, including choreographic pieces, a system of training<br />

and movement technique, as well as industry practices.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 05

This report does not discuss<br />

WHETHER classical ballet is<br />

relevant to modern society. It<br />

explores how an existing<br />

relevance can be maintained,<br />

extended and renewed: It is a<br />

toolbox for the industry.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 06

OBJECTIVES &<br />

HOW TO USE THIS REPORT<br />

This report compiles insights from the literature as well as current<br />

industry leaders. It is important to note that these participants, as<br />

anyone coming from within the dance industry, will have a biased<br />

and inflated view of its relevance due to their enhanced exposure to<br />

as well as dependence on it. This report does not aim to discuss the<br />

question of whether classical ballet as a form of art is or is not<br />

relevant to modern society. Rather, it aims to explore how an existing<br />

relevance can be maintained, extended and renewed; or a lack of<br />

relevance – should it exist – can be created. The following findings<br />

aim to function as a resource for decision-makers, creators and artists<br />

in the classical dance industry <strong>by</strong> providing a glossary-type overview<br />

of themes and practical considerations in keeping with modern times<br />

and facilitating a more easy and profound connection with audiences.<br />

The report is organised in 8 sub-sections that refer to fields that<br />

contribute to relevance in and of dance. Each subsection will feature<br />

several parts of that field and a brief paragraph that discusses how<br />

they pertain to the topic of relevance as well as practical steps that<br />

might be taken in that area to promote increased social traction.<br />

Whilst readers may decide to approach the report chronologically,<br />

this format invited them to use the table of contents to direct their<br />

attention to sections and topics of particular interest to their work.<br />

This report presents neither an exhaustive nor complete list of the<br />

elements contributing to an industry’s continued role in modern<br />

society; it is also not a prescriptive list of all the things a company or<br />

creative in the industry should be thinking about, doing, and/or<br />

engaging with. It is an open resource for inspiration and reflection.<br />

In this, it builds on an understanding that learning from one another<br />

and exploring new ideas remains at the heart of our practice. In this<br />

spirit, it can offer invaluable lessons in cultural renewal which are<br />

expected to contribute to a shared ambition of promoting the<br />

continued relevance of the dance heritage and its accessability.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 07

THE INTERVIEWEES<br />

It has been a pleasure to interview inspiring leaders<br />

and creatives of the European dance scene.<br />

Get to know them before reading about their ideas.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 08

MAśDELEINE oNNE<br />

dominic antonucci<br />

AśNDREW MCNICOL<br />

AśLAśSTAśIR MAśRRIOTT<br />

KAśTY SINNAśDURAśi BEM<br />

RICHAśRD BERMAśNGE<br />

CRYSTAśL COSTAś<br />

The current Artistic Director of The Finnish National<br />

Ballet, looks back on over 16 years experience as a<br />

Director of established ballet companies, including<br />

the Royal Swedish Ballet and Hong Kong Ballet, as<br />

well as a distinguished career as a dancer.<br />

The Assistant Director of Birmingham Royal Ballet,<br />

has a long history with the company. Before<br />

assuming the position, he had a successful dance<br />

career of his own and staged various British works<br />

and heritage pieces internationally.<br />

Freelance choreographer, the Artistic Director of his<br />

own company, McNicol Ballet Collective, as well as<br />

an Artistic Associate at English National Ballet<br />

School. His choreographies are known to use the<br />

classical language in an inventive and fresh way.<br />

An internationally established freelance<br />

choreographer working within as well as beyond the<br />

dance industry. Looking back on a successful dance<br />

career with the Royal Ballet, his works honour the<br />

classical movement vocabulary.<br />

The Artistic Director of Brecon Festival Ballet, the<br />

first company in Wales to show a full professional<br />

production of The Nutcracker. Her exceptional<br />

contribution to the dance culture in Wales was<br />

honoured with a British Empire Medal in 2020.<br />

The Creative Director of English National Ballet<br />

Youth Company, a performance company that gives<br />

young dancers in training an opportunity to collect<br />

company experience, also enjoys a vibrant career as<br />

a choreographer and teacher.<br />

Staging Akram Khan's World War I memento Dust<br />

with Ballett Dortmund at the time of the interview,<br />

the Canadian also works as a guest teacher with<br />

several international companies. Beforehand, she<br />

was a First Soloist with English National Ballet.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 09

HERITAGE, APPROPRIATION<br />

& EVOLUTION<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

One cannot think about the ‘ballet’ as one heritage. Ballet iself is<br />

neither novel nor autonomous in its conception or development. It<br />

carries within it the heritage of folk dance and court mannerism<br />

from which it evolved, and thus appears as a modernisation of a<br />

previous tradition itself (Brinson, 1989; DeValois, 1957). As<br />

developped as a form of art, this process of drawing inspiration<br />

from other traditions, of appropriation and modernisation, has<br />

been ongoing and even instrumental to its success. Castro (2018)<br />

describes for example how the exposure of Spain to Les Ballets<br />

Russes’ The Rite of Spring effected subsequent developments in<br />

Spanish as well as Russian dance: He credits Les Ballets Russes’<br />

use of first Russian and then Spanish folk dance elements in<br />

productions for the success of the works as well as the root<br />

inspiration for the development of several Spanish touring<br />

companies in turn. This example highlights a second important<br />

aspect in ballet’s identity, or ‘non-identity’ as a ‘heritage’: It’s<br />

international context. Ballet sits at the crossroads between<br />

national and international culture. Even though many countries<br />

nowadays have a unique national ballet heritage, ballet is<br />

distinguished <strong>by</strong> a shared approach to movement at the<br />

international level, as well as, global similarities in consumption<br />

patterns as well as a universal symbolic standing. This springs<br />

from vibrant exchange in the early ballet industry in the form of<br />

international tours. Subsequent artistic inspiration increasingly<br />

intertwined and assimilated different national traditions (Castro,<br />

2018). Exemplary of this is Diaghilev’s ballet Las Meninas, which<br />

escapes definity in its adherence to a national tradition in being a<br />

production that appears as and is paying hommage to Spanish<br />

folklore culture yet remains inherently Russian in its heritage as a<br />

piece of the original repertoire of Les Ballets Russes.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 10

Even though the ballet industry’s shared approach to movement has been<br />

institutionalised into a conglomerate of varied national traditions as different<br />

schools of dance emerged as ‘national form(s) of creative self-expression’ (DeValois,<br />

1957: 963), they remain part of a shaed tradition. “Each new incarnation [of The<br />

Nutcracker], from professional to amateur to Nutcracker on Ice, claims imperial<br />

Russian parentage” (Fisher, 2003: 5). For our industry today, this means that the<br />

tradition and heritage we speak about henceforth is not one, but each national<br />

heritag posesses a complex identity rooted in shared international histories of<br />

creative development that have been institutionalised within the nation state.<br />

One cannot think of 'ballet'<br />

as one heritage.<br />

Ballet as we know it today bears a heritage of older styles of dance, as well as a<br />

continued practice of appropriation and evolution at the crossroads of being an<br />

international practice finding its identity as heritag in the national sphere. This<br />

report cannot take on the task of untangling and re-working these complex pasts<br />

and does not aim to be a – albeit much needed – critical take on the nature of what<br />

is conidered classical heritage. Instead, it turns towards the continued practice of<br />

ballet in the 21st century, framing the tradition in its shared technical and aesthetic<br />

approach to movement and repertoire. This is done in an attempt to make a<br />

practical contribution to reconciling a controversial practice with modern social<br />

standards and demands, fostering a more consolidated future for ballet in the 21st<br />

century.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 11

BALLET CRITICISM &<br />

RELEVANCE TODAY<br />

Ballet as practiced and presented today is often criticised for its<br />

political incorrectness and distorted approach to the body, for<br />

being out of touch with contemporary dynamics and relying on<br />

falsified reproductions of the past (Segal, 2006). Headlines read ‘5<br />

Things I Hate About Ballet’ (Los Angeles Times) and Jennifer<br />

Homans famously declared the death of ballet in her 2010 book<br />

‘Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet’. Studies across the globe find<br />

an alarming discrepancy in the immense popularity of social<br />

dancing on the one hand, and the lack of interest in ballet on the<br />

other, which often ranks as one of the least popular art forms<br />

(Schnell, 2014).<br />

Madeleine Onne rejects these notions and makes a strong<br />

argument for the success of classical ballet. She points to high<br />

ticket sales in her company in Finland, which she interprets as a<br />

continued hunger to see live production, saying “as long as people<br />

fill our opera houses or venues all over the world when there's a<br />

classical ballet, I would say it is relevant.”<br />

It is important to note that the popularity of ballet — or a lack<br />

thereof — does not necessarily say anything about its social<br />

relevance. Many Artistic Directors in fact draw a difference<br />

between relevance and appreciation: Whilst the audience might<br />

not appreciate a work of choreography, it might still be relevant to<br />

them, society at large and the advancement of the art form in<br />

itself (Schnell, 2014). This report dives into that latter<br />

understanding of relevance. It does not argue whether ballet is or<br />

is not relevant. Rather, it explores how a relation to the audience,<br />

a social impact and an awareness of modern realities can be<br />

fostered and expanded so as to ensure a continued relevance of<br />

ballet, irrespective of whether that relevance is present and/or<br />

reckognised in the first place.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 12

HERITAGE PRESERVATION<br />

It is impossible to speak about the continued relevance of a cultural tradition without<br />

acknowledging the role of preservation. If we follow Katy Sinnadurai’s view, then<br />

classical ballet is as part of a wider cultural heritage, likening it to important<br />

architectural buildings or famous works of art, which are worthy of preservation in and<br />

of themselves. As we speak about tools to put such a form of heritage more in touch<br />

with society, we need to be aware of the inherent change that process bears, and the<br />

potential impact it might have on the tradition going forward. Whilst this report<br />

cannot offer a thorough review of the concepts around preservation, this section will<br />

briefly discuss ideas around heritage preservation as they pertain to the succeeding<br />

pool of resources and the idea of social relevance.<br />

Preserving a heritage does not always mean keeping it static. Johnson and Snyder<br />

(1999) suggest that preservation is a means of giving value to culture. That definition<br />

means that any attempt at heightening the social traction of classical ballet becomes<br />

an act of preservation in itself. Going one step further, it has also been proposed that<br />

the very nature of dance as a practice escapes preservation in the traditional sense.<br />

This is because dance contains intangible elements such as the knowledge inherent to<br />

the practitioner of the heritage artifact, the performer, or its contextual nature in<br />

spanning across different forms of media and semantics (Mallik et al., 2011). Hybrid<br />

modes of performance, for example work of British artist Ruth Gibson, posesses a<br />

uniquely temporal nature of performance art whose very nature poses a threat to its<br />

existence as heritage due to lack of reproduceability (Whatley, 2013). Even though this<br />

line of thought generates a sense of ‘the impossible’ when it comes to conserving<br />

ballet as a heritage, it does bear practical suggestions that celebrate the momentary<br />

and intangible nature of ballet: Firstly, it condemns locking a choreography up in strict<br />

preservation for example <strong>by</strong> legal means. This prevents the work to develop its full<br />

creative identity through continued re-enactment and actualisation (Lepecki, 2010).<br />

Actualisation can be described as ‘displacement <strong>by</strong> which the past is embodied only in<br />

terms of a present that is different from that which it has been’ (Deleuze, 1991: 71). It<br />

challenges the notion of archives as spaces of preservation and — following Foucault’s<br />

notion of transformation — sees the acting body as the true archive of the dance<br />

(Lepecki, 2010), as well as its inherent renewal. In a reassuring way, these ideas imply<br />

that whilst our efforts at preservation might be futile and misguided, the very practice<br />

of dance carries within it a core relevance in its contextual and performed nature. How<br />

we can embrace those aspects for industry practices is discussed further in Section II:<br />

The Nature of Ballet.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 13

On the other end of the spectrum, recent years have seen a large increase in<br />

interest and initiatives in heritage preservation. Different tools of documentation,<br />

often linked to technological advancements such new video technology, have<br />

facilitated dance documentation and distribution (Johnson and Snyder, 1999). It is<br />

suggested that today, modern web technologies and multimedial approaches to<br />

documentation have overcome the above described time/space dichotomy that<br />

callenges dance preservation (Johnson and Snyder, 1999). Using the example of<br />

Indian dance, Mallik et al. demonstrate how digital ontologies that link resources<br />

and cultural knowledge artifacts <strong>by</strong> concept recognition can build an intelligent<br />

contextual system of heritage preservation (Mallik et al., 2011). Such tools have<br />

become a key feature in reconstructing and reviving past works (Johnson and<br />

Snyder, 1999). Given the importance of preservation <strong>by</strong> means of documentation<br />

and archival work, the American Dance Heritage Coalition’s project manager Smith<br />

(2012), calls for increased funding for archival staff, space and projects. She<br />

believes that combined with the DHC’s education initiatives and expanding<br />

collaborations with academic scholars as well as digital collections, they are key to<br />

the survival of the classical tradition. Andrew McNicol believes in the value of this<br />

kind of preservation because he sees paticularly traditional repertory as an<br />

important source informing the future of ballet <strong>by</strong> way of reflection. To him, ‘some<br />

of the heritage works are really important in helping us understand what has come<br />

before and how we can build on that or evolve that, or move in a different direction<br />

to that. The importance of having those reference points is key.’ Documentation<br />

work can help such referential preservation efforts.<br />

The following report does not take a stand on which take on preservation is or<br />

should be preferred. It does value archival work and documentation as much as<br />

spontaneity and the momentary nature of performance art. It therefore wants to<br />

encourage companies and creators to reflect on their own view on the interplay of<br />

relevance and preservation <strong>by</strong> offering a range of ideas as described above.<br />

A WORD ON CONTEMPORARY DANCE<br />

Many participants picked up on the common notion of seeing younger, more<br />

contemporary dance styles as ‘the modern’ and ballet as ‘the old-fashioned’, as<br />

Madeleine Onne put it. This research is based on a parralel appreciation of both<br />

forms as advocated <strong>by</strong> several interviewees. Whilst it explores topics of crossfertilisation,<br />

collaboration and modernisation, it does not see ballet eventually<br />

evolving into, or being replaced <strong>by</strong> contemporary dance, and the thought and tools<br />

offered hereafter do not aim at that purpose. Rather, they want to evolve ballet and<br />

its industry in its own way and right.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 14

SECTION II<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 15

elements of<br />

relevance<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 16

THE NATURE<br />

OF BALLET<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 17

Is ballet inherently} relevant?ć What constitutes the<br />

unique appeal of classical dance and howw can wwe take<br />

advantage of it to wwiden our social impact?ć<br />

GOVERNMENT<br />

The process of social traction is set in the public sphere. In the<br />

context of ballet, historically, this is the National sphere, as ballet<br />

institutions would often have been created <strong>by</strong> Royal decree or<br />

similar national public bodies (Bonnin-Arias, et al. 2021). As a<br />

public body, the art of ballet finds itself in the realm of<br />

government: It gains authority in being a national symbol of<br />

heritage. This symbolism is acquired through endorsement <strong>by</strong> the<br />

public sphere, which gives ballet institution power to dictate what<br />

is relevant to and reflective of the interests of society. In Bordieu’s<br />

(1992) eyes, ballet as a form of cultural capital constitutes a<br />

powerful tool in offering an institutional framework for creating<br />

an objectified vision and representation of a social group, a<br />

society. Practically, this means that the theatre stage takes a<br />

representative function of ‘showing the life of (a) people’ in the<br />

international realm (DeValois, 1957: 964). In this representation, it<br />

acts as a guideline of the represented reality, what is shown to ‘be’<br />

becomes as what ‘should be’. In more concrete terms, Brinson<br />

(1989) explains that the dance community exerts influence on<br />

society <strong>by</strong> showcasing and therewith endorsing, selling a certain<br />

style of movement, fashion, music, etc. In this powerful nature, it<br />

bears inherent relevance as a determinant of social and cultural<br />

realities (Brinson, 1989). This view offers reassurement to the<br />

industry, testifying to its inherent ability to connect with society in<br />

its own political nature. It migh also nudge leaders in the industry<br />

to reflect on the social power their visions and works exude.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 18

VALUE SYSTEM<br />

Peter Anastos, former Director of Ballet Idaho, proposes that ballet’s strong<br />

adherence to a strict set of values around form and aesthetics enables it to<br />

maintain its identity throughout changing periods of history and associated<br />

fashions (Schnell, 2014). Audiences appreciate classical works for their beauty and<br />

commitment to a certain aesthetic, states Crystal Costa in agreement.<br />

Besides the dedication to a specfic movement aesthetic, Madeleine Onne suggests<br />

that the values of the artists in the industry themselves inherently seek growth in<br />

the art form, which in turn ensures continuous progress. She says: “[O]verall artists<br />

are eager that we go further the whole time. (…) They are hungry to constantly go<br />

forward. (…) That is what is making thing relevant, that even if we do a Swan Lake,<br />

we are not relaxing on the whole Swan Lake thing saying, yeah, we just do it the<br />

easy way. No, we constantly feel like, okay, how can we do it fresher?” It is<br />

important to acknowledge and celebrate both — the industry’s dedication to a<br />

movement aesthetic as well as its artists’ spirit of renewal that serves the industry<br />

as a driving force for innovation and relevance.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 19

PERFORMANCE ART<br />

A ballet rendition poseses a unique tempo-spatial specificity. A<br />

performance is bound in place and time as well as the uniqueness<br />

with which it inhibits a body. Against this background, the act of<br />

re-enactment in itself signifies a renewal and reinvention of the<br />

original work in a new body-time-space construct that surpasses<br />

any attempt at static preservation (Lepecki, 2010). Expressing this<br />

idea In simpler terms, Peter Anastos expresses that ballet<br />

manages to stay relevant <strong>by</strong> the very nature of dance being a<br />

performed artform, presented <strong>by</strong> evolving bodies and techniques<br />

that themselves evolve a production from its original version to a<br />

contemporary presentation (Schnell, 2014). Costa agrees, pointing<br />

out that the ongoing evolution of the physical abilities of dancers<br />

offers a source of intrinsic renewal even without innovations in a<br />

classical piece’s makeup and choreography. She advises that “to<br />

keep (ballet) relevant, we have to keep allowing that athleticism<br />

to shine through with keeping the heritage of the style”.<br />

Andrew McNicol takes a different approach to ballet’s performed<br />

nature, highlighting its temporal nature as a movement language.<br />

He explains: ‘What I love about ballet is it's a language of the<br />

present tense. There's nothing about it that says yesterday I did,<br />

unless you start going into mime, but the actual language itself,<br />

it's totally 100 percent in the present moment. So there is a<br />

vibrancy and a liveliness to that, which I can't help but feel is,<br />

relevant, compelling, exciting.’ Both of these bodies of thought<br />

emphasize the embedded ‘contemporary’ nature of performance<br />

art as a lived phenomenon. Tapping into this characteristic can<br />

expand the excitement of a ballet performance McNicol speaks<br />

about.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 20

WORKMANSHIP<br />

William Forsythe famously declared: ‘Ballet is Olympian’. The dedicated training<br />

required, extreme physical workload as well as extraordinary bodily of dancers<br />

place them amongsth elite level athletes. Madeleine Onne sees this physicality of<br />

ballet as a selling point. She thinks that in the same way that people are interested<br />

in waching sports and high-calibre athletes, they are fascinated <strong>by</strong> ballet. Peter<br />

Anastos equally sees ballet’s relevance in the physical achievements and aesthetic<br />

realities it propagates, as well as the workmanship embedded within them. ‘The<br />

commitment [of dancers] is astonishing, it's an Olympic effort to get through a<br />

training and to have a career. That in itself is a remarkable thing that should be<br />

celebrated’, agrees Andrew McNicol. Continuing to honour and showcase the<br />

extreme workmanship that goes into the ballet practice is an important piece in<br />

helping audiences apprecite this heritage and its lived reality.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 21

TECHNIQUE<br />

‘They say if you can play classical guitar, you can play almost anything. Whereas if<br />

you're a rock guitarist and you've only studied rock, maybe you can't achieve being<br />

a classical guitarst so easily. I feel the same way about ballet and that's probably<br />

the most important reason for keeping the classical ballet tradition alive and a very<br />

high standard.’ This is Domonic Antonucci’s way of explaining the importance of the<br />

classical ballet technique to the wider dance culture. Many choreographers share<br />

his view: McNicol believes in the adaptability and brilliance of ballet technique as a<br />

creative language and thus advocates the preservation of ballet as a creative<br />

medium. Marriott explains that he uses the classical movement language “because<br />

it's probably the most versatile, because technically an artistically and musically,<br />

there are so many facets to classical ballet. It makes a very easy template to make<br />

ballet on.” He believes it’s unique technical features — the long lines of an<br />

arabesque or the height of its aerial lifts — offer unique movement repertory to<br />

choreographers that cannot be replaced <strong>by</strong> another movement language. He adds,<br />

“I don't see it as a kind of obstruction because you can bend the rules as much as<br />

you want.” Dominic Antonucci resonates this view of classical ballet technique as a<br />

strong base for creation, both within and beyond the classical genre. To him,<br />

classical ballet acting as a core of technique and physical training that inspires<br />

other genres of dance, saying ‘those skills and vocabulary can be brought to other<br />

genres quite readily.’<br />

Katy Sinnadurai goes one step further. She sees even potentially outdated parts of<br />

the classical technique as a part of its unique expressive appeal. Reflecting on the<br />

convention of wearing pointe shoes, she says ‘I wouldn't get rid of pointe work at<br />

all, but it is a strange and painful thing to put women through. I think the way that<br />

we can justify carrying on this classical tradition is to say, this is our language. Our<br />

way of connecting with our audience is with our bodies and this particular<br />

technique. Even though it's a very weird technique and only a tiny percentage of<br />

the population will ever do, it's still the language. We're still humans using our<br />

language to connect with you, it's that particular way of talking.’ Tapping into this<br />

unique movement language of the ballet technique is a celebration of the classical<br />

heritage and a testimony to its continued relevance.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 22

If you can play classical guitar, you can play<br />

almost anything. Whereas if you're a rock<br />

guitarist and you've only studied rock, maybe<br />

you can't achieve being a classical guitarst<br />

so easily. I feel the same way about ballet.<br />

– Dominic Antonucci<br />

However, Sinnadurai criticises developments in the ballet industry that place too<br />

much focus on technical abilities. She thinks that ‘because we're pursuing this ever<br />

rising technical bar, we leave behind 95% of the audience.’ She sees this as a way of<br />

‘playing to each other’, given that only the small audience — people already within<br />

the ballet — world will appreciate extraordinary technical achievements. In her<br />

eyes, ‘the majority of the people sitting in the audience don't know if someone has<br />

a good balance or not.’ This is a call to embed technique within choreography in a<br />

balanced and audience-oriented way. It does however not question the inherent<br />

relevance of the classical technique as unique and powerful movement language, as<br />

well as a core creative resource to the wider industry.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 23

THE SOCIAL<br />

CONTEXT<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 24

Howw does the social standing of dance influence its<br />

impact?ć Do current affairs play} a role in our wwork?ć<br />

Howw do wwider developments wwithin social practices and<br />

technologies influence our practice?ć<br />

STAUTS<br />

Historically, a high social status would attracts capital through<br />

public endorsements. This is vital in preventing marginalisation.<br />

The Spanish bolero tradition for example was marginalised due to<br />

its lack of high art status and associated endorsement <strong>by</strong> the<br />

upper classes (Bonnin-Arias, et al., 2021). In a similar manner,<br />

today’s ballet industry is often dependent on wealthy beneficiaries<br />

and institutions to provide financial support, which in turn is not<br />

seldom based on the distinguished nature of ballet as an art form.<br />

Beyond capital, status will play a role in attracting viewers: The<br />

Nutcracker’s popularity in post-war America stemmed partly from<br />

its upper-class status, which attracted those targeting and<br />

experiencing upwards social mobility (Fisher, 2003). Even though<br />

a high social status plays has thus often been instrumental in<br />

enabling ballet, it is nowadays often perceived to be a limiting<br />

factor for ballet’s accessiblity and expansion: Social stigma around<br />

dance and ballet as an elitist form of art lead to a lack of exposure<br />

and thus relevance (Rockwell, 2006; Schnell, 2014). <strong>Modern</strong><br />

creators are invited to contemplate the social status their work<br />

plays to and leans on, whilst funders are encouraged to adapt a<br />

more varied view of classical dance.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 25

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENTS<br />

How a public will receive a certain ballet piece is partially dependent on wider<br />

social developments and concerns (Castro, 2018). Fisher (2003) credits this<br />

mechanism with The Nutcracker’s popularity in 20th century America. The<br />

experience The Nutcracker gave the American public — immersing them in an<br />

exciting, partly exotic journey within the safe and orderly context of the dream tale<br />

tamed in the end — played to a stable family community and a simple celebration<br />

of tradition aligned with social desires and communal nostalgia at a time of vast<br />

industrial change (Fisher, 2003). In a similar manner, early Spanish reviews of The<br />

Rite of Spring praised its democratic nature after the establishment of the Second<br />

Republic in Spain (Castro, 2018). Alastair Marriott infers that changes in social<br />

context mean that classical productions will appear differently to different<br />

generations. In this process, he values the visions of the past seen in traditional<br />

works as conversation-starters and mirrors of the change that society has<br />

experienced since their inception. This is particularly pertinent when thinking about<br />

how changing acceptability standards are increasingly revealing problematic<br />

representations and storylines in many classical ballet pieces. Andrew McNicol<br />

points out that all forms of art are subject to changed perceptios rooted an evolving<br />

society and nonetheless remain important reflections of a past way of life. To him,<br />

this process can be a great source of creativity as new works emerge that tackle<br />

outdated elements in traditional productions.<br />

Beyond the ways in which a work is perceived <strong>by</strong> the public, Whatley (2013) argues<br />

that the practice of dance itself will bear a reflection of a changing society, saying<br />

that ‘dancing bodies embody particular pedagogies and philosophies of movement’.<br />

He questions in how far these realities make ways into what is consiered heritage<br />

due to their temporal nature and rootedness in an evolving social and bodily reality.<br />

Even so, this line of thought would advocate a dance practice that favours<br />

increased agency of the dancing artist, improvisation and regular renewal of<br />

choreographic aesthetics so as to make room for the inherent modernity of the<br />

moving body to emerge. How this can be done is discussed in the section ‘Good<br />

Practice’.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 26

CURRENT AFFAIRS<br />

Beyond wider social developments, Andrew McNicol sees an immediate interaction<br />

with current affairs in his works. He believes that ‘because we're living, it's a living<br />

art form, we are responding to what's happening’. Recalling a commission for<br />

Philadelphia’s Ballet X, he explains: ‘There was one section, which was a pas de<br />

deux between two men. It was essentially a fight. One of the guys was white and<br />

one of the guys was black. Two days prior to the show, there had been a shooting in<br />

Philadelphia, a white police officer shot a black man. I remember we were<br />

rehearsing and the ballet mistress beside me after we had done that section was<br />

quite emotional. I said to her, what's happening for you, what's going on? She said,<br />

it's taken on a new meaning and poignancy, because of what's just happened and<br />

therefore what's in people's mind.’ He encourages choreographers to leave their<br />

works open to these individual projections as they can deepen the impact and<br />

significance of a piece for the audience.<br />

TECHNOLOGICAL<br />

DEVELOPMENTS<br />

Domminic Antonucci points out that a large part of classical ballet’s continued<br />

relevance lies in a natural process of evolution along the lines of technological<br />

advancements: ‘For instance the tights that dancers wear: The tights that I was<br />

wearing in the 90s, are not the tights that we wear today. The comfort level is<br />

different, the material is different, the look is different. (…) Things move along and<br />

evolve and grow. For every department, whether it's wardrobe or lighting or the<br />

stage crew, there are new tools, there's new knowledge, so there's an evolution<br />

there.’ This reassuring reflection reminds us as an industry to embrace progress and<br />

pursue innovation in all areas of our work.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 27

RELATIONS<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 28

Through wwhich structural channels do wwe engage wwith<br />

society}?ć What is the role of the media in helping us<br />

connect wwith our audiences?ć Does the cohesion the<br />

dance industry} affect its ability} to remain relevant?ć<br />

Howw can wwe move closer to audiences in alternative<br />

engagement formats?ć<br />

GOVERNMENT<br />

RELATIONSHIP<br />

Art is a public good, and as such often relies on support from<br />

public institutions. The financial and idealistic support Marius<br />

Petipa for example received from the Russian Tsars laid a path for<br />

the success of Russian classical ballet as a cultural heritage into<br />

the present day (Tomina, 1945). In the reverse case, tense<br />

relationships with government could hinder social relveance and<br />

artistic development, which is why Brinson (1989) calls for a<br />

relaxation of institutional pressures on national companies to<br />

allow for more creative freedom (Brinson, 1989). Crystal Costa<br />

calls for increased public funding for the arts. At the same time<br />

she is acutely aware of the moral background to decisions around<br />

public funding attribution, expressing deep concern over<br />

competition between social causes such as homelessness or<br />

health care and cultural initiatives. In spite of complex intragovernmental<br />

decisions, she advocates building positive<br />

relationships with public bodies to build funding avenues.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 29

CROSS-SECTOR RELATIONS<br />

Ballet foms part of a wider dance and performance sector with a wide variety of<br />

actors, artist unions to theatre venues to charity initiatives. Across this cultural<br />

sector, a strong shared voice can magnify it’s political agency (Brinso, 1989).<br />

McNicol suggests that strengthening relationships in the sector and the wider arts<br />

could have a positive impact on our creative practices. Referencing pieces of<br />

classical music that maintain their popularity in spite of problematic histories, he<br />

suggests that we look at what other classical arts are doing to draw parallels and<br />

understand our shared conversation about relevance on a deeper level.<br />

Beyond the cultural scene, there have been successful initiatives that bring modern<br />

audiences in touch with classical dance through cross-sector networks. The way the<br />

American Dance Heritage Coalition works cooperatively with other institutions in<br />

the industry as well as archives and libraries, is identified as a major contributor to<br />

the securing of dance heritage into the future (Foley, 1999). The ‘America’s<br />

Irreplaceable Dance Treasures’ exhibition is another successful example of a<br />

collaborative approach that encourages public dance literacy <strong>by</strong> integrating<br />

practitioners, academics, journalists and students and creating an accessible format<br />

that put selected works of dance in context to explain their significance (Smith,<br />

2021). Those ways of working show us that reaching out to professionals from other<br />

backgrounds and exploring new ways of sharing our ambitions is an exciting field<br />

of opportunity to expand the public resonance of classical dance.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 30

INTERNATIONAL<br />

EXCHANGE<br />

Intercultural encounters enrich a local cultural scene and foster a<br />

deeper understanding of its significance (Johnson and Snyder,<br />

1999). Historically, there are strong interdependences in the<br />

development of national dance traditions that can be traced back<br />

to lively international exchange (DeValois, 1957).<br />

The Russian and Spanish dance cultures for example drew<br />

inspiration from one another and became increasingly<br />

intertwined in through the Spanish tours of Les Ballets Russes<br />

(Castro, 2018). This led to the development of heritage ballets in<br />

Spain, and the appropriation of Spanish folklore for Russian<br />

productions in turn, for example seen in Diaghilev’s ballet Las<br />

Meninas. The Nutcracker, brought to the US as an ‘immigrant’<br />

production from Russia in the late 19th century, even went so far<br />

as to become the work of ballet most intimately associated with<br />

notions of American identity and values (Fisher, 2003). As an<br />

industry, we gain inspiration and cross-fertilisation from<br />

international exchange and company tours. Costa suggests<br />

touring is moreover a great way to expand exposure and<br />

generate interest, and asks cities to think of hosting a ballet<br />

company for a night as a similar investment to hosting a large<br />

sports event.<br />

Mobility can also create a broader vision for individual creatives,<br />

believes Richard Bermange. He encourages artists to seek out<br />

experiences in different places, asking if you've been in one<br />

institution for your entire career, how would you ever gain<br />

autonomy within your own practice?’<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 31

PUBLIC RELATIONS<br />

& MEDIA<br />

‘Exposure is (…) the first step to relevance’ (Schnell, 2014: 41). Reviewing a range of<br />

actions taken <strong>by</strong> dance companies to embrace modern audiences, Schnell (2014)<br />

describes ballet’s negative public image as the main hurdle to its continued<br />

relevance. In short, ‘(c)lassical ballet has a public relations problem’ (Brinson, 1989:<br />

697).<br />

To Brinson (1989), a first way to address this is changing ballet coverage in print<br />

media. He points to the importance of dance criticism and reportage in shaping the<br />

role of ballet in society. His suggestion is that journalistic coverage should be<br />

ample, aware of the significance of dance and focused on the deeper artistic<br />

dimension of staged works. In order to achieve this, companies might want to<br />

provide more tailored insights events or informational resources for the press.<br />

Beyond print media, the emergence of the film industry has taken an important role<br />

in changing ‘the public’s appetite for, and acceptance of, dance’ (Johnson and<br />

Snyder, 1999: 7), as well as increasing its portability and accessibility (Fisher, 2003).<br />

Because of this, many directors today, for example Lourdes Lopez, AD of Miami City<br />

Ballet, speak in favour of increased broadcasting and televising of ballet when<br />

asked what ballet needs to flourish in the future (Carman and Cappelle, 2014). This<br />

can be done in many different ways: Alastair Marriott would like to see increased<br />

distribution of online content via digital platforms or television channels such as<br />

SkyArts. Katy Sinnadurai points to public live streaming of performances, which can<br />

eliminate financial access barriers and thus helps reach as wide an audience as<br />

possible.<br />

Expanding the view to wider media exposure, Crystal Costa highlights the large<br />

amout of publicity and marketing dedicated to sports. She argues that this heavy<br />

exposure biasses the public’s preferences towards sports rather than culture. This<br />

insight stresses the importance of widespread and engaging media campaigns in<br />

culivating a social appetite for ballet.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 32

AUDIENCE - BUILDING<br />

Audiences are not random. It is a conscious and strategic effort to build and<br />

cultivate them. Katy Sinnadurai therefore points out that it is important to chose the<br />

first time a viewer is introduced to ballet with care. She suggests that they should<br />

be exposed to something that is entertaining and easily understandable, for<br />

example Romeo and Juliet. ‘Once somebody is committed and on board and wants<br />

to see more, then they're going to be interested in the whole spectrum of things<br />

and more modern work, more challenging works’, she says. This insight might be<br />

particularly relevant for new companies or initiatives looking to attract viewers<br />

unfamiliar with classical ballet.<br />

Taking a more long-term view, Andrew McNicol underscroes the significance of<br />

shaping and fostering an ongoing audience relationship, saying ‘I think the<br />

challenge is about cultivating an audience that wants to see new things and<br />

acknowledges and is excited about the fact that sometimes it will work, sometimes<br />

it won't’. To him, this helps the industry function more freely. ‘Ballet X in<br />

Philadelphia are a great example of that, because they're very much a creation<br />

company and it's new and they built a community and an audience there, which<br />

goes to see the work more so to see how the dancers are responding to the<br />

challenges posed <strong>by</strong> the choreographers, instead of going because of the name of<br />

the choreographer. There's something quite liberating and freeing in that.’<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 33

EDUCATION<br />

Rachel S. Moore — former Executive Director and CEO of American Ballet Theatre —<br />

points out that the consumption of ballet as a visual art is highly correlated to<br />

having been exposed to it as a child (Carman, 2007). Madeleine Onne would<br />

therefore like to encourage schools to take students to see ballet performances, so<br />

as to creates an early familiarity with the genre and experience that reduces bias<br />

later in life. Beyond visual exposure, Dame Ninette de Valois credits the extensive<br />

practice of early ballet education for creating a ‘dance-conscious’ nation in mid-<br />

19th century Britain (DeValois, 1957: 963). It is therefore proposed that classical<br />

ballet take advantage of the power that lies within its teaching <strong>by</strong> being part of the<br />

national curriculum in public and private education alike. This can counteract<br />

marginalisation of the art as well as confinement to a specific audience (Brinson,<br />

1989). Costa joins these calls for schools to include basic ballet alongside other<br />

sports in the PE curriculum, believing that this will ceate e a sense of<br />

understanding of and admiration for its physical demands. Additionally, she<br />

advocates for teaching of dance history.<br />

Beyond primary education, integrated higher education scholarship can broaden<br />

society’s understanding of the social functions of dance, for example in connection<br />

with anthropology or psychology. Such education and the corresponding<br />

scholarship should particularly enable creatives and choreographers to create more<br />

integrated work (Brinson, 1989). Promoting widened scholarship in the reverse,<br />

Dana Caspersen, Dancer and Choreographer with The Forsythe Company holds the<br />

corresponding view that young dancers should experience exposure and education<br />

in non-dance-related fields so as to widen their awareness of social dynamics which<br />

can then be incorporated more easily into their practice (Carman, 2007).<br />

Besides curricula and programmes, educational institutions play an important role<br />

in realising these ambitions. Libraries, for example, ‘can be the catalysts in creating<br />

a new awareness of dance as a rewarding resource. Libraries can expose new<br />

audiences to a full understanding of dance through environments as inspiring as<br />

stage performance venues’ (Johnson and Snyder, 1999: 15). They do this <strong>by</strong> offering<br />

in-depth background information that enables a better understanding of the art<br />

form. Audiences and creators alike are encouraged to re-think libraries as important<br />

local actors, resources, and even partners, in increasing interest and understanding.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 34

OUTREACH & ENGAGEMENT<br />

Engaging in dance even just as a leisure<br />

activity will <strong>by</strong> default inspire wider<br />

interest in the art form (Wagner, 1997).<br />

Besides widening audiences and attracting<br />

new interest, outreach and engagement<br />

programmes are also a precious way of<br />

making a positive impact on local<br />

communities. Birmingham Royal Ballet’s<br />

Dominic Antonucci sees great potential in<br />

expanding outreach programmes and ways<br />

of bringing ballet to audiences that go<br />

beyond stage performance. ‘I would like<br />

see ballet made available to anyone not<br />

just to watch, but to be involved with, to<br />

love and to experience in whatever<br />

capacity they might wish. So whether you<br />

have a disability, or you are from another<br />

culture that may have a complicated<br />

relationship with dance, wherever you're<br />

coming from, that you can be involved in<br />

it. Whether you want to design costumes<br />

for it, whether you want to actually<br />

participate in dance yourself or perform, I<br />

would love to see that become wider and<br />

more all-encompassing.’ He imagines<br />

extended access to ballet classes for<br />

varying ability levels, or performances in<br />

the companies’ smaler facilities that are for<br />

and with minority groups. This vision takes<br />

a broad approach to relevance that<br />

saturates society in a profound way.<br />

Freefall Dance<br />

Company<br />

The Freefall Dance Company<br />

is a company offshoot from<br />

Birmingham Royal Ballet. Set<br />

up in 2002, it provides highquality<br />

dance training and<br />

performance opportunities<br />

for people with severe<br />

learning disabilities such as<br />

Down Syndrome.<br />

Dance for<br />

Parkinson's<br />

The Dance for Parkinson’s<br />

programme, which is for<br />

example offered <strong>by</strong> English<br />

National Ballet, offers dance<br />

sessions to people with<br />

Parkinson’s disease to<br />

facilitate a reduction in their<br />

medical symptoms.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 35

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION<br />

The social roots of dance lie in community culture, and and used to serve an<br />

experience rather than an entertainment purpose. The Rennaissance changed the<br />

function of dance in society, separating performer and audience so that dance<br />

became something be experienced <strong>by</strong> viewing rather than participating (Johnson<br />

and Snyder, 1999). However, innovative projects today are reversing those<br />

dynamics, acknowledging that participation and dance play an important part in<br />

community formation and social cohesion (McNeill, 1995).<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 36

PARTICIPATION CASE STUDY<br />

Brecon Festival Ballet<br />

Katy Sinnadurai’s Brecon Festival Ballet is such a public participation initiative: Her<br />

The Nutcracker is a full-scale professional production based on a communityparticipation<br />

approach. Whilst it features a professional orchestra and professional<br />

dancers in the lead roles, erything else is done <strong>by</strong> people from outside the industry<br />

on a volunteer basis. This begins on stage, where local children and adults assume<br />

character roles. In the party scene, real local granddads are on stage portraying the<br />

grandfathers, whilst the corps de ballet is formed <strong>by</strong> dance students. Sinnadurai<br />

found that this variety brought liveliness and realistic human interaction to the<br />

production. She also points out that ‘<strong>by</strong> having 99 people on stage in total, 15 of<br />

who were professionals, 20 of who were students and the rest were local, that<br />

massively increased our audience because everybody wanted come to see the<br />

person they know.’ Even though not every production lends itself to this<br />

participation-based approach, ‘Nutcracker has roles that you could put non-dancers<br />

into as long as they can walk in time with the music and do a basic partner dance.<br />

We did have auditions to make sure that they could do that’, explains Sinnadurai.<br />

She does however concede that it remains important to her to have professional<br />

dancers in the lead roles to maintain a high standard.<br />

Beyond stage appearances, about 150 members of the local community made<br />

costumes, painted scenery and did fundraising. Sinnadurai herself stands behind<br />

Brecon Festival Ballet on a voluntary basis out of a profound belief in its value for<br />

the local community. Throughout the production process, she received exceptional<br />

feedback from participants. The process of coming in every week and rehearsing<br />

helped people meet each other, explore new talents, and find new passions. She<br />

testifies to great social and even mental health benefits for the community<br />

springing from this mode of involvement.<br />

How can we reconstruct this format elsewhere? Sinnadurai credits the unique<br />

characteristics of an already tight-knit local commmunity in a small town, which<br />

she is a longstanding part of, with the exceptional local effort and success of her<br />

vision. Therein lies a great encouragement for talent rooted in other similar<br />

communities to think of setting local impulses through artistic initiatives.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 37

PROGRAMME &<br />

PRODUCTIONS<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 38

Howw can wwe structure an artistic season in a wway} that<br />

serves the audience as wwell as the industry}?ć Can and<br />

should wwe re-ėwwork heritage pieces in order to keep them<br />

relevant?ć What role do neww commissions play}?ć<br />

PROGRAMMING<br />

Programming is an important strategic tool in building and<br />

cultivating an audience relationship. Madeleine Onne takes a<br />

broad approach when preparing a season programme for The<br />

Finnish National Ballet, aiming to have a balanced repertory<br />

that attracts a wide audience. She thinks, ‘there should be<br />

something for everyone. It should be something for those<br />

who are more adventurous, it should be something for those<br />

who want a story ballet, something for the families,<br />

something that's more challenging. Something old and<br />

something new.’ Alastair Marriott agrees that the diversity<br />

within dance should be reflected through a balanced<br />

programme of works and encourages audiences to appreciate<br />

modern work alongside classical pieces. Sinnadurai also<br />

highlights the importance of balance in terms of mood and<br />

contents, saying: ‘I'm beginning to think of an idea of a ballet<br />

that I want to say something about our impact on the<br />

environment, but I would do it in a mixed bill that ends with<br />

a load of fun, because I don't think people want to go to the<br />

theatre to be preached at.’<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 39

These kind of mixed programmes are often said to be more<br />

succeessul than traditional story ballets in attracting large<br />

audiences (Schnell, 2014; Carman 2007). Onne challenges this<br />

perception, pointing out that audiences that would likely<br />

appreciate shorter ballets are those that are often less likely to<br />

frequent an opera house and will thus not attend the very triple<br />

bills created for them. Sinnadurai’s solution to this is to combine<br />

old and new in a mixed programme. She suggests that particularly<br />

people visiting ballet for the first time will be likely to see a show<br />

they have heard of, which will be a heritage piece such as Swan<br />

Lake or The Nutcracker. In order to retain this name appeal but also<br />

introduce a wider spectrum of ballet, she suggests programming<br />

triple bills with one piece that presents on extracts, or just one act,<br />

from a heritage production.<br />

Beyond attracting an audience through the variety and balance of a<br />

season, programming is also a tool to shape the relationship with<br />

the audience <strong>by</strong> forming the preferences of that very audience.<br />

Stephen Mills — Director of Ballet Austin — mentions the<br />

importance of intelligent programming so as to gradually introduce<br />

complex pieces and build the audience’s understanding and taste<br />

in the long-term (Schnell, 2014).<br />

Looking at developments in the wider industry, Marriott stresses<br />

the importance for companies to tune into a unique artistic identity<br />

through programming that returns from a global shared repertory<br />

to local diversity. Rather than encouraging the ‘loudest ten voices’<br />

to be heard across the globe <strong>by</strong> way of a shared international<br />

repertory, this would make space for more choreographic variety,<br />

making company tours more interesting and rewarding for foreign<br />

audiences. Onne has successfully exemplified this approach: When<br />

programming the 100-year anniversary season for The Finnish<br />

National Ballet, she commissioned a Made in Finland triple bill<br />

that exclusively features Finnish choreographic talent. To her, this<br />

is also a way of giving her audience something to be proud of and<br />

honouring their contribution to the national culture sector: ‘I want<br />

the Finnish people to feel that they should be proud of their<br />

national company that they're paying for (through taxes).’<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 40

CLASSICAL COMMISSIONS /<br />

RE-WORKING HERITAGE<br />

Ballet’s devotion to tradition is sometimes criticised as a way of living in the past.<br />

This criticism overlooks the fact that ballet’s heritage choreographic works are — as<br />

described <strong>by</strong> several interviewees — often the ones that are most successful<br />

commercially. Beyond their popularity, they have a role to play in maintaining<br />

ballet’s relevance: Scholl (2014) suggests that as much as Diaghilev’s modernisation<br />

of early Russian ballet was what rapidly increased the art’s global popularity, a<br />

return to older works and technical aspects was what fortified it’s success<br />

afterwards through the Russian ‘classical’ revival. He describes this process as a<br />

‘retrospectivism’, a way of taking inspiration from ideals and aesthetics that<br />

predated Russian ballet’s first modernisation to inspire the second one (Scholl,<br />

2014). Along similar lines of thought, Richard Bermange describes the tension<br />

between tradition and modernity as a source of creative interest. He believes that<br />

“the story of ballet is a conflict always. So it's important that we keep bouncing off<br />

each other. Without it, we're saying the same things again. And it makes it exciting,<br />

as long as the new really is new and as long as we're looking at the old with new<br />

eyes.” What he suggests is that heritage pieces should be presented in fresh ways to<br />

appeal to modern audiences.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 41

Madeleine Onne on the other hand explains that when commissionning classical<br />

pieces, she sees value in emphasizing traditional and timeless qualities of a<br />

production, pointing out that they are large investments that are expected to stay<br />

with a company for at least 10 years. Whatley (2013) seconds this view, listing<br />

reproduceability as an important consideration in building and maintaining a<br />

heritage.<br />

I want something that can survive in<br />

10 to 20 years, because it's such a<br />

huge, huge investment. So in<br />

classical commissions, I want something<br />

traditional and special for us.<br />

– Madeleine Onne<br />

Crystal Costa acknowledges that there are different ways of re-working classical<br />

pieces, arguing that all have their place. Whether it be a story re-interpreted in a<br />

new language of movement as in Akram Khan’s Giselle, or an adaptation focusing on<br />

renewing the story and integrated production elements whilst keeping with the<br />

classical movement repertoire, for example Tamara Rojo’s Raymonda. Alastair<br />

Marriott follows the latter line of thought, advising that classical stories can be<br />

revived <strong>by</strong> making them more historically accurate. ‘You set (them) in a more<br />

realistic village, and you can do much more research into what the real clothes<br />

would look like. And when you do additional choreography, you can study all the<br />

other versions and make a decision as to which bits are really important and which<br />

bits need to be updated.’ Conversely, Madeleine Onne is in favour of adapting some<br />

elements of classical pieces away from their original version and towards a reality<br />

that is more reflective of the audience’s life. For this reason, The Finnish National<br />

Ballet’s Swan Lake for example features snow to reflect the Finnish climate, which<br />

makes the production more relatable to local audiences.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 42

NEW COMMISSIONS<br />

Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon has made it clear that new commissions bring<br />

excitement to the industry (Carman, 2007). In the eyes of Madeleine Onne, they<br />

offer a space to celebrate the growing variety of different dance styles as a source<br />

of cross-fertilisation. In commissioning new ballets, she often invites contemporary<br />

choreographers, suggesting that “contemporary choreographers working with<br />

classical dancers usually inspire each other and that takes the art form to explore<br />

new ways”. In this, she is careful to ensure that the physical abilities of classical<br />

dancers are taken advantage of, so as to highlight the unique qualities of ballet<br />

amongst more modern dance formats.<br />

From the commissionnee’s point of view, Alastair Marriott calls choreographers to<br />

lean into restrictions posed upon them <strong>by</strong> a particular commission, suggesting that<br />

being limited to a specific set of parameters can generate creative solutions and<br />

new ways of thinking. In this creative process of generating new work, Richard<br />

Bermange warns of uncconscious pastiche, suggesting that “if you really want to<br />

make a change, you have to question yourself a lot and repeatedly to make sure<br />

that you're always on the right track. Keep referring back to the question, it's like<br />

doing an essay.”<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 43

GOOD PRACTICE<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 44

Does the idea of relevance play} a role in our daily}<br />

practice?ć Howw can wwe design and share the artistic<br />

process to amplify} its impact?ć What role does the<br />

artistic agency} of the individual dancer play},Ā and howw<br />

can wwe encourage this from a y}oung age?ć<br />

RE-ENACTMENT<br />

Re-enactment – or more simply repetition — is a powerful<br />

tool. In scholarship, it has been described to drive the<br />

continued contemporaneity of a choreographic piece through<br />

the act of actualisation (Lepecki, 2010). This process of<br />

actualisation is described as a ‘displacement <strong>by</strong> which the<br />

past is embodied only in terms of a present that is different<br />

from that which it has been’ (Deleuze, 1991: 71). This<br />

understanding rests on the relevance ballet achieves in being<br />

a performed art as described in earlier sections. In pactical<br />

terms, it means what Alastair Marriott said in his interview:<br />

The traditional ballet repertoire should continue to form part<br />

of our practice. It contain choreography whose unique<br />

difficulty offers dancers a platform for technical and artistic<br />

growth. In this the very act of repetition and inherent<br />

actualisation contributes to the growing excellence in the<br />

physicality of the wider art form. Crystal Costa seconds this<br />

view, saying that the classical technique is a unique source of<br />

learning and intelligence for the dancer’s body. She sees<br />

continued practice of classical choreography as a driving<br />

factor of advances in dance physicality due to the unique<br />

challenges they pose for a dancer’s technique and stamina.<br />

<strong>Classical</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong> // <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Society</strong> 45

THE ARTISTIC PROCESS<br />

Andrew McNicol shines a light on the importance of an intentional artistic process.<br />

In his own practice, he makes sure to be very clear about what a specific<br />

combination of environment, group of artists, time frame and culture lend<br />

themselves to in terms of artistic impact. To understand and integrate this well into<br />

his work, he has found it important to get to know the artists and environment they<br />

work in before beginning the artistic process. In building that rapport, McNicol<br />