Justice Trends Magazine #7

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ISSN 2184–0113<br />

issue / Edición nr. 7<br />

Semester / semestre 1 2021<br />

JUSTICE SYSTEMS<br />

IN TRANSITION<br />

SISTEMAS DE JUSTICIA<br />

EN TRANSICIÓN<br />

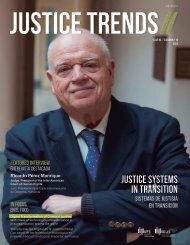

Featured interview<br />

Entrevista destacada<br />

Didier Reynders<br />

European Commissioner<br />

Comisario Europeo<br />

<strong>Justice</strong> / Justicia<br />

In focus / En el foco<br />

COVID-19:<br />

Challenges and opportunities<br />

for correctional systems<br />

Desafíos y oportunidades<br />

para los sistemas penitenciarios<br />

The New European Bauhaus:<br />

Towards beautiful, sustainable<br />

and inclusive prisons<br />

Hacia cárceles hermosas,<br />

sostenibles e inclusivas<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 1

2 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

EDITORIAL<br />

THE OPPORTUNITY THAT EMERGED FROM CHAOS<br />

La oportunidad que surgió del caos<br />

For a long time, heads of correctional administrations have prepared for<br />

different threat scenarios. But this time, it was different. The COVID 19<br />

pandemic has taken us all by surprise and hit hard, showing how vulnerable<br />

our organisations can be. Despite the lack of resources experienced in<br />

many jurisdictions, it is imperious to recognise the effort of all of those<br />

men and women who have worked tirelessly to minimise the contagion<br />

and its disastrous effects in challenging conditions.<br />

To all of you, “thank you”.<br />

Throughout your career, you may have experienced your version of<br />

Irving Zola’s parable. In the parable, a man sees someone going down<br />

the river current. The man saves the first person in the water only to be<br />

drawn to the rescue of more drowning people. After rescuing many, the<br />

man questions himself how it would be if instead of keeping jumping<br />

into the water, saving people, he would have the time to walk upstream<br />

and understand why so many people have fallen into the river. As in<br />

corrections, Zola’s story illustrates the tension between public protection<br />

mandates and the need to respond to emergencies (helping the people<br />

caught in the current) and prevention and promotion mandates (stopping<br />

the people from falling into the river).<br />

Taking the time to search for solutions upstream often leads us to the<br />

root causes of the problem and understanding that complex problems<br />

require collaborative solutions based on the inter-institutional cooperation<br />

between the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> stakeholders and between these and other<br />

government services.<br />

Often faced with limited resources, heads of prison administrations were<br />

asked to act fast in a context of high uncertainty: organising to produce<br />

and provide protective equipment for staff and inmates; improving<br />

detention conditions and hygiene of correctional facilities; adapting and<br />

readjusting the work of staff, including the shifts of frontline staff and<br />

remote work of others; providing training and communicating with staff<br />

and inmates and inmates’ families, conveying messages that nobody was<br />

sure about and that could change in the next day; restricting inmate’s<br />

movements and outside contacts – including court hearings; suspending<br />

family visits, education and training activities; ensuring and managing<br />

testing, quarantines and isolation; caring for the sick and the dead and<br />

their families; managing the vaccination process, but as well implementing<br />

the safety and compensation measures to reduce pressure and anxiety<br />

that could endanger the security of all.<br />

The changes that we have witnessed are unprecedented. In some months,<br />

correctional services adopted solutions that would take years or decades<br />

to be implemented in normal circumstances. The promotion and adoption<br />

of alternative measures to incarceration - including pardons, the broader<br />

use of community sanctions and electronic monitoring; the adoption of<br />

remote work; the implementation or strengthening of technology-based<br />

solutions, allowing inmates to be in frequent contact with their families<br />

(prolonged and more frequent phone communications and video-calls),<br />

Durante mucho tiempo, los responsables de las administraciones<br />

penitenciarias se han preparado para diferentes escenarios de amenazas.<br />

Pero esta vez fue diferente. La pandemia de COVID 19 nos ha tomado a<br />

todos por sorpresa y nos ha golpeado con fuerza, mostrando lo vulnerables<br />

que pueden ser nuestras organizaciones. A pesar de la falta de recursos<br />

experimentada en muchas jurisdicciones, es imperioso reconocer el esfuerzo<br />

de todos aquellos hombres y mujeres que han trabajado incansablemente para<br />

minimizar el contagio y sus efectos desastrosos en condiciones desafiantes.<br />

A todos ustedes, “muchas gracias”.<br />

A lo largo de su carrera, es posible que haya experimentado su versión de<br />

la parábola de Irving Zola. En la parábola, un hombre ve a alguien que baja<br />

por la corriente del río. El hombre salva a la primera persona en el agua<br />

solo para ser atraído al rescate de más personas que se están ahogando.<br />

Después de rescatar a muchos, el hombre se pregunta cómo sería si en<br />

lugar de seguir saltando al agua, salvando gente, tuviera tiempo para<br />

caminar río arriba y entender por qué tanta gente se ha caído al río. Como<br />

en los sistemas penitenciarios, la historia de Zola ilustra bien la tensión<br />

entre los mandatos de protección pública y la necesidad de responder a<br />

las emergencias (ayudando a las personas atrapadas en la corriente) y los<br />

mandatos de prevención y promoción (evitar que la gente caiga al río).<br />

Tomarse el tiempo para buscar soluciones aguas arriba a menudo nos lleva<br />

a las causas fundamentales del problema y a comprender que los problemas<br />

complejos requieren soluciones colaborativas, basadas en la cooperación<br />

interinstitucional entre las partes interesadas de la Justicia Penal y entre<br />

estas y otros servicios gubernamentales.<br />

A menudo, enfrentados con recursos limitados, se pidió a los responsables<br />

de administración penitenciaria que actuaran con rapidez en un contexto<br />

de alta incertidumbre: organizarse para producir y proporcionar equipos de<br />

protección individual para el personal y los reclusos; mejorar las condiciones<br />

de detención y la higiene de los establecimientos penitenciarios; adaptar y<br />

reajustar el trabajo del personal, incluidos los turnos del personal de primera<br />

línea y el trabajo remoto de otros; brindar capacitación y comunicación<br />

con el personal y los internos y sus familias, transmitiendo mensajes de las<br />

que nadie estaba seguro y que podrían cambiar al día siguiente; restringir<br />

los movimientos de los reclusos y los contactos externos, incluidas las<br />

vistas judiciales; suspender las visitas de familiares, las actividades de<br />

educación y formación; asegurar y gestionar las pruebas, las cuarentenas<br />

y el aislamiento; cuidar de los enfermos y de los muertos y sus familias;<br />

gestionar el proceso de vacunación, pero también implementar las medidas<br />

de seguridad y compensación para reducir la presión y la ansiedad que<br />

podrían poner en peligro la seguridad de todos.<br />

Los cambios que hemos presenciado no tienen precedentes. En algunos<br />

meses, los servicios correccionales adoptaron soluciones que tardarían años<br />

o décadas en implementarse en circunstancias normales. La promoción y<br />

adopción de medidas alternativas al encarcelamiento, incluidos los indultos,<br />

el uso más amplio de sanciones comunitarias y monitoreo electrónico; la<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 3

EDITORIAL<br />

the implementation of video visitation and virtual court hearing solutions,<br />

the use of telemedicine and e-learning, among others.<br />

Are we now better prepared for the future?<br />

I have no doubts about it. But our preparedness will depend on our<br />

capacity to assimilate and mainstream the lessons that emerged from the<br />

pandemic. Going back to “normal” should be about “normalising” the new<br />

practices. We must find the time to reflect on how the use of alternatives<br />

to incarceration may endure beyond the crisis period. Find the time to<br />

rethink existing detention regimes and conditions or imagine new futures<br />

adopting new ways of working and working together. Find the time to<br />

reflect on embracing technology and the challenges of digitisation (for<br />

some) or digital transformation (for others). Don’t we do this, and we<br />

would have lost the great opportunity that emerged from chaos.<br />

In this new edition of the JUSTICE TRENDS magazine, we have invited<br />

the European Commissioner for <strong>Justice</strong>, Ministers and Secretaries of<br />

<strong>Justice</strong>, Director-generals, representatives of NGO’s and experts from<br />

around the world to share their views on how they’ve faced the pandemic<br />

and their opinions about the future. //<br />

I hope you enjoy reading.<br />

Pedro das Neves<br />

CEO IPS_Innovative Prison Systems<br />

Director of the JUSTICE TRENDS <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Director Ejecutivo IPS_Innovative Prison Systems<br />

Director de la revista JUSTICE TRENDS<br />

pedro.neves@prisonsystems.eu<br />

adopción del trabajo a distancia; la implementación o fortalecimiento<br />

de soluciones basadas en la tecnología que permitan a los reclusos estar<br />

en contacto frecuente con sus familias (comunicaciones telefónicas<br />

prolongadas y más frecuentes y videollamadas), la implementación de<br />

soluciones de visitación por video y audiencias virtuales con tribunales,<br />

el uso de telemedicina y educación a distancia, entre otros.<br />

¿Estamos ahora mejor preparados para el futuro?<br />

No tengo ninguna duda al respecto. Pero nuestra preparación dependerá de<br />

nuestra capacidad para asimilar e incorporar las lecciones que surgieron de<br />

la pandemia. Volver a la "normalidad" debería consistir en "normalizar" las<br />

nuevas prácticas. Debemos encontrar tiempo para reflexionar sobre cómo el<br />

uso de alternativas al encarcelamiento puede perdurar, más allá del período<br />

de crisis. Buscar el tiempo para repensar los regímenes y condiciones de<br />

detención existentes o imaginar nuevos futuros, adoptando nuevas formas<br />

de trabajar y trabajar juntos. Encuentre el tiempo para reflexionar sobre<br />

cómo adoptar la tecnología y los desafíos de la digitalización (para unos)<br />

o la transformación digital (para otros). Si no hacemos esto, habremos<br />

perdido la gran oportunidad que surgió del caos.<br />

En esta nueva edición de la revista JUSTICE TRENDS, hemos invitado<br />

al comisario Europeo de Justicia, ministros y secretarios de Justicia,<br />

directores generales, representantes de ONG's y expertos de todo el mundo<br />

a compartir sus puntos de vista sobre cómo han enfrentado la pandemia<br />

y sus opiniones sobre el futuro. //<br />

Espero que disfrute leyendo.<br />

Scan my business card<br />

Escanear mi tarjeta de visita<br />

Data sheet | hoja técnica<br />

Publisher | Editor:<br />

IPS_Innovative Prison Systems (QUALIFY JUST IT Solutions and Consulting Ltd)<br />

Director and Editor-in-chief | Director y Jefe de Redacción: Pedro das Neves<br />

Editorial team | Equipo editorial:<br />

Pedro das Neves, Sílvia Bernardo<br />

Interviews | Entrevistas: Pedro das Neves, Sílvia Bernardo<br />

Interviewees | Entrevistados:<br />

Anne Kelly, Christine Montross M.D., David Brown, Deborah Richardson, Didier Reynders,<br />

Fiorella Salazar Rojas, Ina Eliasen, Ivan Zinger PhD, Jan Kleijssen, Nivaldo Restivo, Rómulo<br />

Mateus, Rudy Van De Voorde, Victor Dickson<br />

Contributing authors | Contribuciones:<br />

Ana Maria Evans & Pedro das Neves, Are Høidal, Dave Lageweg (Telio), Francis Toye (Unilink),<br />

Hans Meurisse, Jennifer Oades & Diane Williams, José Demetrio (Geosatis), Marayca Lopez,<br />

ODSecurity, Pia Puolakka, Robert Boraks, Roni Weinberg (Attenti), Steve Carter, Steven van<br />

de Steene<br />

Partners in this edition | Socios en esta edición:<br />

Attenti, Geosatis, ODSecurity, Telio, Unilink<br />

Periodicity | Periodicidad: Bi-annual | Bianual<br />

Design | Diseño: Sílvia Silva, Paula Martinho<br />

Revision and translation | Revisión y traducción: M21Global<br />

Printed by | Impresión: JG Artes Gráficas, Lda.<br />

Circulation | Tiraje: 2000 copies / ejemplares<br />

International Standard Serial Number<br />

Número Internacional Normalizado de Publicaciones Seriadas:<br />

ISSN 2184 – 0113<br />

Legal Deposit | Depósito Legal: 427455/17<br />

Ownership of | Propiedad de:<br />

IPS Innovative Prison Systems<br />

(QUALIFY JUST IT Solutions and Consulting Ltd)<br />

PARKURBIS 6200–865 Covilhã, Portugal<br />

ips@prisonsystems.eu | www.prisonsystems.eu<br />

© JUSTICE TRENDS <strong>Magazine</strong> 2017-2021<br />

The published articles are the sole responsibility of the respective author(s) and do not<br />

necessarily reflect the opinion of the JUSTICE TRENDS editors. Neither the publisher/owner nor<br />

any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use that may be made of the<br />

information contained therein. Despite the necessary edition, the editorial team tries to keep<br />

the contents as close to the original as possible. The reproduction of this publication is not<br />

authorised except for a one-off request, however, it still requires a written consent from its<br />

owner and publisher.<br />

Los artículos publicados son responsabilidad exclusiva de(l) los respectivos autores y no reflejan<br />

necesariamente la opinión de los editores de la Revista JUSTICE TRENDS. Ni el editor/propietario<br />

ni ninguna persona que actúe en su nombre pueden responsabilizarse por el uso que pueda<br />

hacerse de la información contenida en el mismo / los mismos. A pesar de la necesaria edición,<br />

el equipo editorial trata de mantener los contenidos lo más cerca posible del original. La<br />

reproducción de esta publicación no está autorizada, excepto en una situación puntual, sin<br />

embargo, todavía requiere un consentimiento por escrito de su propietario y editor.<br />

4 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

Corrections<br />

Learning Academy<br />

www.correctionslearning.online<br />

Grow your expertise in Corrections<br />

Specialised online courses<br />

Each course is an interactive textbook, featuring<br />

videos, virtual training sessions, e-Learning<br />

materials, quizzes, projects and assignments.<br />

Flexible learning journey<br />

Build up your correctional skills at anytime, and<br />

anywhere, at your own pace with self-paced or<br />

group and tutored programmes.<br />

Insightful live masterclasses<br />

Enrol in a masterclass with a dedicated tutor<br />

and get personalised one-on-one mentoring.<br />

̌<br />

̌<br />

̌<br />

Expert tutoring<br />

Certified instructors<br />

Growing virtual community<br />

Start here<br />

Pick a course<br />

Purchase it<br />

Get your credentials<br />

Take the course<br />

Get your certificate<br />

Corrections<br />

Learning Academy<br />

Special plans for Correctional Agencies<br />

Unlock your agency’s status to get exclusive discounts<br />

Register for an annual subscription for a minimum number of users — the more<br />

you have, the more you save — and get personalised assistance along the way.<br />

/corrections-learning-academy<br />

/CorrectionsLearningAcademy<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 5

CONTENTS<br />

CONTENidos<br />

3<br />

10<br />

18<br />

26<br />

32<br />

Editorial<br />

The opportunity that emerged from chaos / La oportunidad que surgió del caos<br />

By / por: Pedro das Neves, Director JUSTICE TRENDS <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Respect for the rule of law at the core of the justice portfolio<br />

El respeto del estado de derecho en el centro de la cartera de Justicia<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Didier Reynders<br />

European Commissioner for <strong>Justice</strong>, European Commission<br />

Comisario Europeo de Justicia, Comisión Europea<br />

<strong>Justice</strong> and Peace: challenges and advancements in times of pandemic<br />

Justicia y Paz: retos y avances en tiempos de pandemia<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Fiorella Salazar Rojas<br />

Minister of <strong>Justice</strong> and Peace, Costa Rica<br />

Ministra de Justicia y Paz, Costa Rica<br />

<strong>Justice</strong> and beyond:<br />

Council of Europe working on setting global benchmarks on artificial intelligence<br />

Justicia y más allá:<br />

El Consejo de Europa trabaja para establecer puntos de referencia mundiales en inteligencia artificial<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Jan Kleijssen<br />

Director of the Information Society and Action against Crime Directorate, Council of Europe<br />

Director de la Dirección de Sociedad de la Información y Acción contra la Delincuencia del Consejo de Europa<br />

EXPERTS’ PANEL: THE NEW EUROPEAN BAUHAUS<br />

PANEL DE EXPERTOS: LA NUEVA BAUHAUS EUROPEA<br />

The New European Bauhaus: An opportunity to revisit the way we think about prisons<br />

La Nueva Bauhaus Europea: una oportunidad para revisar nuestra forma de pensar sobre las prisiones<br />

By / por: Ana Maria Evans & Pedro das Neves<br />

The New European Bauhaus: the experts’ view<br />

La Nueva Bauhaus Europea: la opinión de los expertos<br />

Panelists / Panelistas:<br />

Robert Boraks, Architect & Director of Parkin Architects / Arquitecto y director de Parkin Architects<br />

Hans Meurisse, Vice-President, ICPA International Corrections and Prisons Association and<br />

Chairperson of the ICPA European Chapter / Vicepresidente de la Asociación Internacional de<br />

Correccionales y Prisiones (ICPA, por sus siglas en inglés) y Presidente del Capítulo Europeo de la ICPA<br />

Marayca Lopez, <strong>Justice</strong> & Civic Planning Leader, DLR Group / Líder de Justicia y Planificación Cívica, Grupo DLR<br />

Are Høidal, Governor, Halden Prison, Norwegian Correctional Service<br />

Director, Prisión de Halden, Servicio Penitenciario de Noruega<br />

Pia Puolakka, Project manager, Criminal Sanctions Agency of Finland<br />

Directora de proyecto, Organismo de Sanciones Penales de Finlandia<br />

Steve Carter, Founder & Executive Vice-President for Global Strategic Development, CGL Companies<br />

Fundador y vicepresidente ejecutivo de Desarrollo Estratégico Global, CGL Companies<br />

Steven van de Steene, Enterprise architect and Corrections technology consultant<br />

Arquitecto empresarial y asesor tecnológico de servicios correccionales<br />

42<br />

48<br />

51<br />

54<br />

62<br />

Making changes on several fronts: infrastructure, personnel, health and digital<br />

Concretar cambios en varios frentes: infraestructura, personal, salud y digital<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Rudy Van De Voorde<br />

Director-General Belgian Prison Service<br />

Director general del Servicio Penitenciario de Bélgica<br />

Domestic Violence: Do restraining orders really provide protection?<br />

Violencia doméstica: ¿las órdenes de alejamiento realmente brindan protección?<br />

By / por: Roni Weinberg (Attenti)<br />

Smart Prison: a historical digital leap in Finnish prisons<br />

Prisión inteligente: un salto digital histórico en las cárceles finlandesas<br />

By / por: Pia Puolakka<br />

A digital leap in Canada's federal corrections triggered by the pandemic<br />

Un salto digital en los penales federales de Canadá provocado por la pandemia<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Anne Kelly<br />

Commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada<br />

Comisionada del Servicio Penitenciario de Canadá<br />

Social distancing in prison / Distanciamiento social en prisión<br />

By / por: ODSecurity<br />

6 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

CONTENTS<br />

CONTENidos<br />

66<br />

74<br />

76<br />

80<br />

88<br />

90<br />

98<br />

104<br />

106<br />

112<br />

118<br />

126<br />

Challenges and priorities for the Portuguese prison system...<br />

And the ongoing transformation despite COVID-19<br />

Desafíos y prioridades del sistema penitenciario portugués...<br />

Y la transformación en curso a pesar de la COVID-19<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Rómulo Mateus<br />

Director-General of Reintegration and Prison Services, Portugal<br />

Director general de Reinserción y Servicios Penitenciarios, Portugal<br />

Video calls in prisons: current needs and challenges after the pandemic<br />

Videollamadas en prisiones: necesidades actuales y desafíos después de la pandemia<br />

By / por: Dave Lageweg (Telio)<br />

Beyond Prisons: Women and Community Corrections - ICPA TASKFORCE<br />

Más allá de las prisiones: mujeres y correcciones comunitarias - Grupo de trabajo de la ICPA<br />

By / por: Diane Williams & Jennifer Oades<br />

Making a strategic investment to give a big step forward in modernisation<br />

Una inversión estratégica para dar un gran paso adelante en la modernización<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Deborah Richardson<br />

Deputy Solicitor General (Correctional Services), Ontario, Canada<br />

Viceministra (Servicios Correccionales), Ontario, Canadá<br />

Use of offender electronic monitoring expands during pandemic<br />

El uso del monitoreo electrónico de delincuentes se expande durante la pandemia<br />

By / por: José Demetrio (Geosatis)<br />

Challenges and opportunities for a prison system with more than 200,000 inmates<br />

Retos y oportunidades para un sistema penitenciario con más de 200.000 presos<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Nivaldo Restivo<br />

Colonel, Secretary of State for the penitentiary Administration, São Paulo, Brazil<br />

Coronel, Secretario de Estado de la Secretaría de Administración Penitenciaria, Estado de São Paulo, Brasil<br />

Prison overcrowding and staffing problems:<br />

Critical situation leads to unprecedented strategies<br />

Problemas de hacinamiento y personal:<br />

La situación crítica en las prisiones conduce a estrategias sin precedentes<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Ina Eliasen<br />

Director-General, Department of Prisons and Probation, Denmark<br />

Directora general, Departamento de Prisiones y Libertad Condicional, Dinamarca<br />

Making prison and probation work<br />

Hacer que la prisión y la libertad condicional funcionen<br />

By / por: Francis Toye (Unilink)<br />

A focus on reducing recidivism both in custody and community corrections<br />

Un enfoque en reducir la reincidencia tanto en custodia como en correcciones comunitarias<br />

Interview / Entrevista: David Brown<br />

Chief Executive, Department for Correctional Services, South Australia<br />

Director ejecutivo, Departamento de Servicios Correccionales, Australia Meridional<br />

What solutions for the mentally ill caught in the web of a broken criminal justice system?<br />

¿Qué soluciones para los enfermos mentales atrapados en la red de una justicia penal rota?<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Christine Montross, M.D.<br />

Psychiatrist, author of “Waiting for an Echo – The Madness of American Incarceration”, USA<br />

Médica especialista en Psiquiatría, autora de “Waiting for an Echo – The Madness of American<br />

Incarceration”, Estados Unidos de América<br />

Achieving systemic changes through the investigation of inmates' complaints<br />

Lograr cambios sistémicos a través de la investigación de las denuncias de los presos<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Ivan Zinger<br />

Correctional Investigator of Canada / Investigador Correccional de Canadá<br />

An NGO dedicated to assisting (ex)convicts in becoming employed or entrepreneurs<br />

Una ONG dedicada a ayudar a (ex)condenados a conseguir empleo o a ser emprendedores<br />

Interview / Entrevista: Victor Dickson<br />

President and CEO, Safer Foundation, USA<br />

Presidente y director general de la Fundación Safer, Estados Unidos de América<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 7

8 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

We bring corrections<br />

stakeholders together<br />

Network<br />

with industry peers<br />

Connect<br />

with relevant experts<br />

Identify<br />

potential partners<br />

Request<br />

information/quotes<br />

Discuss<br />

use cases/approaches<br />

Publicise<br />

projects/tenders<br />

+1100 members<br />

Join our global business community<br />

for correctional agencies, specialised suppliers, experts, and research organisations.<br />

Take advantage of the network and exposure<br />

to make your projects and procurement opportunities known.<br />

Discover products, services, and technology providers<br />

that are indispensable for your correctional service.<br />

www.corrections.direct<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 9

10 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

Didier Reynders<br />

European Commissioner for <strong>Justice</strong>, European Commission<br />

Comisario Europeo de Justicia, Comisión Europea<br />

Respect for the rule of law at the core of the justice portfolio<br />

El respeto del estado de derecho en el centro de la cartera de Justicia<br />

JT: Prior to serving as European Commissioner for <strong>Justice</strong>, you held various<br />

positions in public institutions as minister (without interruption from 1999<br />

to 2019). Having served as Federal Minister of Finance in six different<br />

governments, then Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs, Trade and European<br />

Affairs in two governments and Minister of Defence, you certainly have<br />

a good understanding of how priorities often differ between the regional,<br />

federal and supra-national levels.<br />

What are the key priorities in the area of <strong>Justice</strong> in Europe, and<br />

how do they align with the Political Guidelines and supra-national<br />

perspective of the European Commission?<br />

DR: My key priorities are to develop European justice systems and judicial<br />

cooperation in light of the digital transition, empower consumers in the<br />

green and digital transitions, safeguard fundamental rights, and promote<br />

the rule of law throughout the European Union.<br />

Respect for the rule of law is at the core of the justice portfolio because all<br />

rights stem from it. The rule of law is a “gateway” to all other fundamental<br />

rights and the mutual recognition of judicial decisions both in civil and<br />

criminal law. To this end, the Commission has established the new<br />

comprehensive European Rule of Law Mechanism, a process for an<br />

annual dialogue between the Commission, the Council and the European<br />

Parliament, the Member States and national parliaments, civil society and<br />

other stakeholders. This new initiative has contributed to the launch of an<br />

EU-wide debate on the promotion of rule of law culture, and the annual<br />

Rule of Law Report is the foundation of this new process. During the first<br />

year of my mandate, I presented the first annual Rule of Law Report, and<br />

the second one is planned for July this year.<br />

I am also fully committed to the correct and full implementation of the<br />

General Data Protection Regulation and the Directive on Data Protection<br />

in Criminal Law Enforcement. We should embrace new technologies.<br />

One of my priorities is the protection of fundamental rights in the digital<br />

age, including by actively contributing to a coordinated approach on the<br />

human and ethical implications of artificial intelligence.<br />

In civil and criminal justice, my priority is to facilitate and improve judicial<br />

cooperation between the Member States and develop the justice area. I<br />

want to ensure that law enforcement and respect for fundamental rights<br />

go hand in hand, especially online. We need to continue building trust<br />

between national legal systems. Citizens’ rights, especially free movement<br />

and the rights conferred by European citizenship, are primordial. At this<br />

level, during the COVID-19 crisis, I was responsible for guaranteeing the<br />

free movement of people, and then I was also involved in the development<br />

of EU-wide instruments to help restore freedom of movement. Last year,<br />

we worked on tracing apps, and we are now setting up the Digital Green<br />

Certificate.<br />

On consumer policy, in November 2019, I presented the New Consumer<br />

Agenda, setting out priorities for consumer rights over the next five years.<br />

Among other ambitions, the Commission aims to empower consumers<br />

in the green and digital transitions. Moreover, I am leading the work on<br />

consumer protection, notably for cross-border and online transactions.<br />

During these COVID times, there has been far greater reliance on digital<br />

transactions, and I have made it my mission to make these more trustworthy.<br />

JT: Antes de servir como comisario europeo de Justicia, ocupó varios<br />

cargos en instituciones públicas como ministro (sin interrupción de 1999<br />

a 2019). Ocupó el puesto de ministro federal de Finanzas en seis gobiernos<br />

diferentes, después fue ministro federal de Relaciones Exteriores, Comercio<br />

y Asuntos Europeos en dos gobiernos y ministro de Defensa, sin duda tiene<br />

una buena comprensión de cómo las prioridades a menudo difieren entre<br />

los planos regionales, federales y supranacionales.<br />

¿Cuáles son las prioridades clave en el ámbito de la Justicia en<br />

Europa, y cómo se alinean con las directrices políticas y la perspectiva<br />

supranacional de la Comisión Europea?<br />

DR: Mis prioridades fundamentales son desarrollar los sistemas de justicia<br />

europeos y la cooperación judicial a la luz de la transición digital, empoderar<br />

a los consumidores en las transiciones ecológica y digital, salvaguardar<br />

los derechos fundamentales y promover el estado de derecho en toda la<br />

Unión Europea.<br />

El respeto del estado de derecho está en el centro de la cartera de Justicia<br />

porque todos los derechos se derivan de él. El estado de derecho es<br />

una «puerta de entrada» a todos los demás derechos fundamentales y al<br />

reconocimiento mutuo de las decisiones judiciales, tanto en el ámbito<br />

civil como en el penal. Con este fin, la Comisión ha establecido el nuevo<br />

mecanismo europeo integral del estado de derecho, un proceso para un<br />

diálogo anual entre la Comisión, el Consejo y el Parlamento Europeo, los<br />

Estados miembros y los parlamentos nacionales, la sociedad civil y otras<br />

partes interesadas. Esta nueva iniciativa ha contribuido al lanzamiento de<br />

un debate en toda la UE sobre la promoción de la cultura del estado de<br />

derecho, y el Informe Anual sobre el Estado de Derecho es la base de este<br />

nuevo proceso. Durante el primer año de mi mandato, presenté el primer<br />

informe y el segundo está previsto para julio de este año.<br />

También estoy plenamente comprometido con la correcta y plena aplicación<br />

del Reglamento General de Protección de Datos y de la Directiva sobre<br />

Protección de Datos en la Aplicación de la Ley Penal. Deberíamos adoptar<br />

nuevas tecnologías. Una de mis prioridades es la protección de los derechos<br />

fundamentales en la era digital, incluso contribuyendo activamente a<br />

un enfoque coordinado sobre las implicaciones humanas y éticas de la<br />

inteligencia artificial.<br />

En justicia civil y penal, mi prioridad es facilitar y mejorar la cooperación<br />

judicial entre los Estados miembros y desarrollar el ámbito de la justicia.<br />

Quiero asegurarme de que la aplicación de la ley y el respeto de los derechos<br />

fundamentales vayan de la mano, especialmente en línea. Tenemos que<br />

seguir fomentando la confianza entre los sistemas jurídicos nacionales.<br />

Los derechos de los ciudadanos, especialmente la libre circulación y los<br />

derechos conferidos por la ciudadanía europea, son primordiales. En este<br />

nivel, durante la crisis de la COVID-19, fui responsable de garantizar la<br />

libre circulación de personas y luego también participé en el desarrollo<br />

de instrumentos en el ámbito de la UE, para ayudar a restaurar la libertad<br />

de circulación. El año pasado, trabajamos en aplicaciones de seguimiento<br />

y ahora estamos configurando el Certificado Verde Digital.<br />

En cuanto a la política del consumidor, en noviembre de 2019 presenté la<br />

Nueva Agenda del Consumidor, que establece las prioridades en materia<br />

de derechos del consumidor para los próximos cinco años.<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 11

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

Moreover, the <strong>Justice</strong> portfolio has a strong external dimension. I continue<br />

to prioritise justice reforms with the European Union’s nearest neighbours,<br />

the Western Balkans, Turkey and the Eastern and Southern neighbourhood.<br />

<strong>Justice</strong> policies are interlinked with many other policy areas. For this<br />

reason, it is crucial to cooperate and make the best use of all talent within<br />

the Commission, in line with the principle of collegiality.<br />

Finally, we are now a few days away from starting the operational activities<br />

of the European Public Prosecutor Office.<br />

EC - Audiovisual Service © European Union, 2020<br />

Commissioner Reynders at the 2020 Annual Rule of Law Report press conference, 30 September<br />

2020 | El comisario Reynders en la conferencia de prensa del Informe anual sobre el<br />

estado de derecho de 2020 30 Septiembre 2020<br />

“<br />

The Commission funds numerous action grants<br />

dedicated to awareness raising and support in<br />

the practical application of the detention-related<br />

Framework Decisions.”<br />

JT: Judicial cooperation in criminal matters within the EU is based on the<br />

principle of mutual recognition of judicial decisions. Different Council<br />

Framework Decisions1 enable not only detention but also prison sentences,<br />

probation decisions or alternative sanctions and pre-trial supervision<br />

measures to be executed in an EU country other than the one in which the<br />

person is sentenced or awaiting trial. These are based on the principle<br />

of mutual trust, which implies that detention conditions and procedural<br />

safeguards are equivalent in all EU Member States. However, there are large<br />

discrepancies, which may raise significant fundamental rights concerns.<br />

Furthermore, due to “a lack of awareness and experience thereof, but<br />

also because of the burdensome administrative procedures that must be<br />

followed” these instruments are not being used by professionals across<br />

Members States as expected.2<br />

The European Commission promotes the widespread awareness and<br />

use of these very important instruments. What is your strategy and<br />

plan to overcome low implementation levels by the Member States?<br />

DR: In November 2019, the Council started a peer review (9th round of<br />

mutual evaluations), addressing both the three detention related Framework<br />

Decisions and the Framework Decision on the European Arrest Warrant<br />

(EAW). This 9th round of mutual evaluation, in which the Commission<br />

participates as an observer, will be finalised by the end of 2021.<br />

Entre otras ambiciones, la Comisión tiene como objetivo empoderar a<br />

los consumidores en las transiciones ecológicas y digitales. Además,<br />

dirijo el trabajo sobre la protección del consumidor, en particular para<br />

las transacciones transfronterizas y en línea. Durante estos tiempos de<br />

COVID, ha habido una mayor dependencia de las transacciones digitales,<br />

y mi misión es hacerlas más fiables.<br />

Además, la cartera de Justicia tiene una fuerte dimensión externa. Sigo<br />

dando prioridad a las reformas de la justicia con los vecinos más cercanos<br />

de la Unión Europea, los Balcanes Occidentales, Turquía y la vecindad<br />

oriental y meridional.<br />

Las políticas de justicia están interrelacionadas con muchas otras áreas<br />

políticas. Por esta razón, es crucial cooperar y aprovechar todo el talento<br />

dentro de la Comisión, de conformidad con el principio de colegialidad.<br />

Por último, estamos a pocos días de iniciar las actividades operativas de<br />

la Fiscalía Europea.<br />

“<br />

La Comisión financia numerosas subvenciones<br />

de acción dedicadas a la sensibilización y el apoyo<br />

en la aplicación práctica de las Decisiones Marco<br />

en materia de detención.”<br />

JT: La cooperación judicial en materia penal dentro de la UE se basa en<br />

el principio de reconocimiento mutuo de las resoluciones judiciales. Las<br />

diferentes Decisiones Marco del Consejo1 permiten no solo la detención,<br />

sino también las penas de prisión, las decisiones de libertad condicional<br />

o las sanciones alternativas y las medidas de supervisión previas al juicio<br />

ejecutarse en un país de la UE distinto del que se condena a la persona<br />

o de donde está en espera de juicio. Estas se basan en el principio de<br />

confianza mutua, que implica que las condiciones de detención y las garantías<br />

procesales son equivalentes en todos los Estados miembros de la UE. Sin<br />

embargo, existen grandes discrepancias que pueden plantear importantes<br />

problemas de derechos fundamentales. Además, debido a «la falta de<br />

conocimiento y experiencia al respecto, pero también debido a los trámites<br />

administrativos engorrosos que deben seguirse», estos instrumentos no<br />

están siendo utilizados por profesionales en todos los Estados miembros<br />

como se esperaba. 2 La Comisión Europea promueve la conciencia<br />

generalizada y el uso de estos instrumentos tan importantes. ¿Cuál<br />

es su estrategia y plan para superar los bajos niveles de aplicación<br />

por parte de los Estados miembros?<br />

DR: En noviembre de 2019, el Consejo inició una revisión por pares<br />

(novena ronda de evaluaciones mutuas), abordando tanto las tres Decisiones<br />

Marco relacionadas con la detención como la Decisión Marco sobre la<br />

Orden de Detención Europea (ODE). Esta novena ronda de evaluación<br />

mutua, en la que la Comisión participa como observadora, finalizará a<br />

finales de 2021. La evaluación mutua aportará un valor añadido, ofreciendo<br />

la oportunidad, con visitas sobre el terreno, de considerar no solo posibles<br />

cuestiones jurídicas, sino especialmente los aspectos prácticos y operativos<br />

pertinentes vinculados a la aplicación de estos instrumentos.<br />

En lo que respecta a la Decisión Marco relativa a la Libertad Condicional<br />

y las Penas Sustitutivas y la Decisión Marco sobre la Orden Europea de<br />

Vigilancia, la evaluación mutua proporcionará información sobre la baja<br />

aplicación de estas dos Decisiones Marco en la práctica, mientras que<br />

también se harán sugerencias de mejora.<br />

1<br />

2002/584/JHA on the European arrest warrant and the surrender procedures between Member States;<br />

2008/909/JHA on the application of the principle of mutual recognition to judgments in criminal matters<br />

imposing custodial sentences or measures involving deprivation of liberty for the purpose of their enforcement<br />

in the European Union; 2008/947/JHA on the application of the principle of mutual recognition to judgments<br />

and probation decisions with a view to the supervision of probation measures and alternative sanctions;<br />

2009/299/JHA amending Framework Decisions 2002/584/JHA, 2005/214/JHA, 2006/783/JHA, 2008/909/<br />

JHA and 2008/947/JHA, thereby enhancing the procedural rights of persons and fostering the application of<br />

the principle of mutual recognition to decisions rendered in the absence of the person concerned at the trial;<br />

2009/829/JHA on the application, between Member States of the European Union, of the principle of mutual<br />

recognition to decisions on supervision measures as an alternative to provisional detention.<br />

2 European Judicial Network. (2019). Report on activities and management 2017-2018. European Union.<br />

https://www.ejn-crimjust.europa.eu/ejnupload/reportsEJN/ReportSecretariat%20.pdf<br />

1<br />

2002/584/JAI sobre la orden de detención europea y los procedimientos de entrega entre Estados miembros;<br />

2008/909/JAI sobre la aplicación del principio de reconocimiento mutuo de sentencias en materia penal por<br />

las que se imponen sentencias de custodia o medidas de privación de libertad a efectos de su cumplimiento<br />

en la Unión Europea; 2008/947/JAI relativa a la aplicación del principio de reconocimiento mutuo de sentencias<br />

y resoluciones de libertad vigilada con miras a la vigilancia de las medidas de libertad vigilada y<br />

las penas sustitutivas; 2009/299/JAI por la que se modifican las Decisiones Marco 2002/584/JAI, 2005/214/<br />

JAI, 2006/783/JAI, 2008/909/JAI y 2008/947/JAI, mejorando así los derechos procesales de las personas y<br />

fomentando la aplicación del principio de reconocimiento mutuo a las decisiones dictadas en ausencia del<br />

interesado en el juicio; 2009/829/JAI sobre la aplicación, entre Estados miembros de la Unión Europea,<br />

del principio de reconocimiento mutuo a las decisiones sobre medidas de supervisión como alternativa a<br />

la detención provisional.<br />

2 Red Judicial Europea. (2019). Informe de actividades y gestión 2017-2018. Unión Europea.<br />

https://www.ejn-crimjust.europa.eu/ejnupload/reportsEJN/ReportSecretariat%20.pdf<br />

12 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

The mutual evaluation will provide added value by offering the opportunity,<br />

with on-the-spot visits, to consider not only potential legal issues but<br />

especially relevant practical and operational aspects linked to the application<br />

of these instruments.<br />

As regards the Framework Decision on Probation and Alternative Sanctions<br />

and the Framework Decision on the European Supervision Order, the<br />

mutual evaluation will provide insights into the low application of these<br />

two Framework Decisions in practice, while suggestions for improvement<br />

will also be made.<br />

Organisations who receive operating grants from the Commission, such as<br />

the European Organisation for Prison and Correctional Services (EuroPris)<br />

and the Confederation of European Probation (CEP) have created specific<br />

Experts Groups on the detention-related Framework Decisions, which<br />

meet on a yearly basis. The Commission funds numerous action grants<br />

dedicated to awareness raising and support in the practical application<br />

of these EU instruments.<br />

As regards detention, the Commission recently launched a study on pretrial<br />

detention, which will feed into the Commission’s assessment of the<br />

need for EU wide rules in this area, for cross border and/or domestic cases.<br />

At the request of, and funded by the Commission, the European Union<br />

Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) launched the Criminal Detention<br />

Database in December 2019. The database combines information on<br />

detention conditions in all EU Member States in one place.<br />

In parallel, to help enhance mutual trust between Member States, since<br />

2010 the European Union has adopted six directives aiming at a high level<br />

of fair trial rights. The Commission is monitoring the effective application<br />

of these directives throughout the European Union. The Commission<br />

has launched infringement proceedings for lack of full transposition of<br />

these directives and has produced implementation reports for the first<br />

four directives.<br />

“<br />

Consolidating a common European judicial<br />

culture, based on the rule of law, fundamental rights<br />

and mutual trust is one of the flagship actions of<br />

the new strategy. The new priorities also include<br />

upscaling the digitalisation of justice and going<br />

beyond legal education to support the development<br />

of professional skills.”<br />

JT: On 2 December 2020, the Commission presented its new and ambitious<br />

Strategy on European Judicial Training for 2021-2024, one of the two<br />

pillars of a package to modernise EU justice systems, side by side with the<br />

digitalisation of justice. The Strategy aims at improving training of justice<br />

professionals on EU law. It widens its scope to new topics, target audiences<br />

and geographical coverage: it addresses challenges such as the exponential<br />

digitalisation of societies and the need to reinforce fundamental rights. For<br />

the first time, prison staff and probation officers are a target audience. While<br />

focusing mainly on the EU Member States, the strategy also addresses the<br />

Western Balkans and beyond.<br />

What would you highlight regarding the objectives, challenges and<br />

how the Commission plans to implement the 2021-2024 European<br />

Judicial Training Strategy?<br />

DR: EU law only serves citizens if properly implemented. The training of<br />

justice professionals on EU law has proved an essential tool for improving<br />

the correct and uniform application of EU law and building mutual trust<br />

in cross-border judicial proceedings. This is why the Commission has put<br />

forward a comprehensive new strategy to respond to the new challenges,<br />

such as those brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, and to support<br />

justice systems in the EU. Moreover, consolidating a common European<br />

judicial culture, based on the rule of law, fundamental rights and mutual<br />

trust is one of the flagship actions of the new strategy. The new priorities<br />

also include upscaling the digitalisation of justice and going beyond legal<br />

Las organizaciones que reciben subvenciones de funcionamiento de<br />

la Comisión, como la Organización Europea de Prisiones y Servicios<br />

Correccionales (EuroPris) y la Confederación Europea de Libertad<br />

Condicional (CEP), han creado grupos de expertos específicos sobre las<br />

Decisiones Marco en materia de detención, que se reúnen anualmente.<br />

La Comisión financia numerosas subvenciones de acción dedicadas a la<br />

sensibilización y el apoyo en la aplicación práctica de estos instrumentos<br />

de la UE.<br />

En cuanto a la detención, la Comisión ha lanzado recientemente un estudio<br />

sobre la prisión preventiva, que se incorporará a la evaluación de la<br />

Comisión de la necesidad de normas a escala de la UE en este ámbito,<br />

para casos transfronterizos y/o nacionales. A petición de la Agencia de<br />

Derechos Fundamentales (FRA) de la Unión Europea, y financiada por la<br />

Comisión, puso en marcha la base de datos de detención penal en diciembre<br />

de 2019. La base de datos combina información sobre las condiciones<br />

de detención en todos los Estados miembros de la UE en un solo lugar.<br />

Paralelamente, para ayudar a mejorar la confianza mutua entre los Estados<br />

miembros, desde 2010 la Unión Europea ha adoptado seis directivas<br />

destinadas a un nivel elevado de derechos relativos a un juicio justo. La<br />

Comisión está supervisando la aplicación efectiva de estas directivas<br />

en toda la Unión Europea. La Comisión ha iniciado procedimientos de<br />

infracción por falta de transposición completa de estas directivas y ha<br />

elaborado informes de ejecución para las cuatro primeras directivas.<br />

“<br />

La consolidación de una cultura judicial<br />

europea común, basada en el estado de derecho,<br />

los derechos fundamentales y la confianza mutua<br />

es una de las acciones emblemáticas de la nueva<br />

estrategia. Las nuevas prioridades también incluyen<br />

ampliar la digitalización de la justicia e ir más allá<br />

de la educación jurídica para apoyar el desarrollo<br />

de habilidades profesionales.”<br />

JT: El 2 de diciembre de 2020, la Comisión presentó su nueva y ambiciosa<br />

estrategia sobre formación judicial europea para 2021-2024, uno de los<br />

dos pilares de un paquete para modernizar los sistemas judiciales de la<br />

UE, junto con la digitalización de la justicia. La estrategia tiene por objeto<br />

mejorar la formación de los profesionales de la justicia en materia de<br />

Derecho de la UE. Amplía su alcance a nuevos temas, audiencias objetivo<br />

y cobertura geográfica: aborda desafíos como la digitalización exponencial<br />

de las sociedades y la necesidad de reforzar los derechos fundamentales.<br />

Por primera vez, el personal penitenciario y los agentes de libertad<br />

condicional son un público objetivo. Aunque se centra principalmente<br />

en los Estados miembros de la UE, la estrategia también se dirige a los<br />

Balcanes Occidentales y más allá.<br />

¿Qué destacaría en relación con los objetivos y desafíos, y cómo la<br />

Comisión planea implementar la Estrategia Europea de Formación<br />

Judicial 2021-2024?<br />

DR: El Derecho de la UE solo sirve a los ciudadanos si se aplica<br />

correctamente. La formación de los profesionales de la justicia sobre el<br />

Derecho de la UE ha demostrado ser una herramienta esencial para mejorar<br />

su aplicación correcta y uniforme y para fomentar la confianza mutua en<br />

los procedimientos judiciales transfronterizos. Por ello, la Comisión ha<br />

presentado una nueva estrategia global para responder a los nuevos desafíos,<br />

como los planteados por la pandemia de la COVID-19, y para apoyar los<br />

sistemas de justicia en la UE. Además, la consolidación de una cultura<br />

judicial europea común, basada en el estado de derecho, los derechos<br />

fundamentales y la confianza mutua es una de las acciones emblemáticas<br />

de la nueva estrategia. Las nuevas prioridades también incluyen ampliar<br />

la digitalización de la justicia e ir más allá de la educación jurídica para<br />

apoyar el desarrollo de habilidades profesionales.<br />

En consecuencia, más profesionales de la justicia deberían asistir a la<br />

formación sobre legislación de la UE y los proveedores de formación<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 13

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

education to support the development of professional skills. Consequently,<br />

more justice professionals should attend training on EU law and training<br />

providers should improve the EU law training on offer, whether national or<br />

cross-border, EU (co-)funded or not. This applies to all justice professionals<br />

who apply EU law, including primarily judges, prosecutors and court staff,<br />

but also professions such as lawyers, notaries, bailiffs, mediators, legal<br />

interpreters/translators, court experts, and in certain situations prison staff<br />

and probation officers.<br />

The training of prison staff and probation officers is crucial to upholding<br />

fundamental rights during detention and consolidating their key role<br />

in preventing radicalisation in prisons, and ensuring the success of<br />

rehabilitation programmes. At the same time, they also need to be aware<br />

of EU policies, in particular on prisoner transfers, probation, alternative<br />

sanctions, supervision, drug-related legislation and other issues in prisons.<br />

The strategy includes a new tool, currently in a test phase with recognised<br />

EU-level training providers: the European Training Platform3. It is a search<br />

tool for justice professionals who want to train themselves in EU law.<br />

It advertises training courses on EU law and training materials for selflearning<br />

and use by trainers. I encourage JUSTICE TRENDS <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

readers to use it.<br />

JT: Following the topic of facilitating and improving judicial cooperation<br />

and the development of the justice area, the Mission Letter that the President<br />

of the Commission addressed to you states that "(…) you must also study<br />

how to make the most of new digital technologies to improve the efficiency<br />

and functioning of our judicial systems".4<br />

How do you support accelerated digitalisation of justice systems,<br />

especially given that the pandemic may have had a boosting effect in<br />

digital transformation processes?<br />

DR: The European Union has supported Member States in their endeavours<br />

towards digitalisation of national justice systems for a long time. However,<br />

it is true that the difficulties experienced by the justice systems of Member<br />

States during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that we had to accelerate<br />

the digital transition. I will mention a couple of examples.<br />

Last December, we adopted a Communication on the Digitalisation<br />

of <strong>Justice</strong> in the EU. This strategy outlines the main objectives for the<br />

development of a digital European justice and proposes a toolbox of<br />

measures to foster the digitalisation of justice both at the national and<br />

cross-border level.<br />

With regard to EU financial support, the Recovery and Resilience Facility<br />

is our main COVID recovery instrument. I personally called on Member<br />

States to plan ambitious digitalisation reforms and investments. Member<br />

States could also benefit from the 2021-2027 cohesion policy funds and<br />

the <strong>Justice</strong> programme.<br />

Our support is not only financial, but is also provided through legislative<br />

measures to facilitate interoperability between national systems and<br />

remove legal barriers to digitalisation. The Commission recently adopted<br />

a legislative proposal on sustainable management and maintenance<br />

of the e-CODEX system. This system is an essential and important<br />

component for the interoperable and secure exchange of information and<br />

data between national courts and competent authorities in cross-border<br />

judicial proceedings. Member States have free access to e-CODEX. By<br />

the end of this year, the Commission is aiming to table a major reform<br />

proposal for the digitalisation of EU cross-border judicial cooperation in<br />

civil, commercial and criminal matters. This proposal is a further step in<br />

modernising judicial cooperation procedures and in making them more<br />

efficient and resilient to crises.<br />

I am confident that the ambitious Commission agenda, and the shared<br />

commitment of Member States to bring justice into the new digital era,<br />

through better use of technologies, will be to the direct benefit to our<br />

citizens, legal practitioners, businesses, and the rule of law as a whole.<br />

deberían mejorar la oferta de formación sobre legislación de la UE, ya<br />

sea nacional o transfronteriza, (co)financiada por la UE o no. Esto se<br />

aplica a todos los profesionales de la justicia que aplican la legislación<br />

de la UE, incluidos principalmente jueces, fiscales y personal judicial,<br />

pero también profesiones como abogados, notarios, agentes judiciales,<br />

mediadores, intérpretes/traductores jurídicos, peritos judiciales y, en<br />

determinadas situaciones, personal penitenciario y oficiales de libertad<br />

condicional. La formación del personal penitenciario y de los oficiales de<br />

libertad condicional es crucial para defender los derechos fundamentales<br />

durante la detención y para consolidar su papel clave en la prevención de la<br />

radicalización en las prisiones y para garantizar el éxito de los programas<br />

de rehabilitación. Al mismo tiempo, también deben tener conocimiento de<br />

las políticas de la UE, en particular sobre las transferencias de presos, la<br />

libertad condicional, las sanciones alternativas, la supervisión, la legislación<br />

relacionada con las drogas y otras cuestiones en prisiones.<br />

La estrategia incluye una nueva herramienta, actualmente en fase de<br />

prueba con proveedores de formación reconocidos en el ámbito de la UE:<br />

la Plataforma Europea de Formación3. Es una herramienta de búsqueda<br />

para los profesionales de la justicia que quieran formarse en el Derecho de<br />

la UE. Anuncia cursos de formación sobre Derecho de la UE y materiales<br />

de formación para el autoaprendizaje y el uso por parte de los formadores.<br />

Animo a los lectores de la revista JUSTICE TRENDS a utilizarla.<br />

EC - Audiovisual Service © European Union, 2020<br />

Discussion between Commissioner Reynders and Ylva Johansson, European Commissioner<br />

for Home Affairs at the weekly meeting of the von der Leyen Commission, in which they<br />

discussed data and artificial intelligence strategies, among other topics. 19 February 2020.<br />

Conversación entre el comisario Reynders e Ylva Johansson, comisaria europea de Asuntos de<br />

Interior en la reunión semanal de la Comisión von der Leyen, en la que se debatieron estrategias<br />

de datos e inteligencia artificial, entre otros temas. 19 de febrero de 2020.<br />

JT: Siguiendo el tema de facilitar y mejorar la cooperación judicial y el<br />

desarrollo del área de justicia, la Carta de Misión que la Presidenta de la<br />

Comisión le dirigió dice que «(…) también debe estudiar cómo aprovechar las<br />

nuevas tecnologías digitales para mejorar la eficiencia y el funcionamiento<br />

de nuestros sistemas judiciales».4<br />

¿Cómo apoya la digitalización acelerada de los sistemas judiciales,<br />

especialmente dado que la pandemia puede haber tenido un efecto<br />

impulsor en los procesos de transformación digital?<br />

DR: La Unión Europea ha apoyado a los Estados miembros en sus esfuerzos<br />

por la digitalización de los sistemas nacionales de justicia durante mucho<br />

tiempo. Sin embargo, es cierto que las dificultades experimentadas por<br />

los sistemas de justicia de los Estados miembros durante la pandemia de<br />

la COVID-19 hicieron que tuviéramos que acelerar la transición digital.<br />

Mencionaré un par de ejemplos.<br />

El pasado mes de diciembre adoptamos una Comunicación sobre la<br />

Digitalización de la Justicia en la UE. Esta estrategia esboza los principales<br />

objetivos para el desarrollo de una justicia europea digital y propone una<br />

caja de herramientas de medidas para fomentar la digitalización de la<br />

justicia tanto en el ámbito nacional como transfronterizo.<br />

3 https://e-justice.europa.eu/european-training-platform/<br />

4 von der Leyen, U. (1 Dec 2019). Mission letter Didier Reynders, Commissioner for <strong>Justice</strong>. https://bit.ly/3fYhxpl<br />

3 https://e-justice.europa.eu/european-training-platform/<br />

4 von der Leyen, U. (1 de diciembre de 2019). Carta de misión Didier Reynders, Comisario de Justicia.<br />

https://bit.ly/3fYhxpl<br />

14 JUSTICE TRENDS // Semester / Semestre 1 2021

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

JT: The 2021-2024 European Judicial Training Strategy refers to the need to<br />

upscale the digitalisation of judicial training and prepare justice professionals<br />

to embrace digitalisation and the use of artificial intelligence.<br />

To what extent has European Commission <strong>Justice</strong> been working on<br />

the issues of human and ethical use of artificial intelligence in criminal<br />

justice systems?<br />

DR: The <strong>Justice</strong> services of the Commission have started working on<br />

Artificial Intelligence (AI) issues in the context of criminal justice. This<br />

work has been recently further developed with the Commission’s adoption<br />

of its overall AI framework. This is ongoing, and the Commission recently<br />

launched an initiative on a European Approach to Artificial Intelligence.<br />

In the Directorate-General for <strong>Justice</strong>, we held a preliminary Expert<br />

Group meeting during which we covered various issues, such as criminal<br />

liability and fundamental rights and data protection aspects. Once the<br />

Commission’s AI Framework has been finalised, we plan to deepen our<br />

work on AI in the judicial and law enforcement context.<br />

“<br />

AI is crucial for our century. It can bring major<br />

benefits for society and the economy, but also<br />

risks. This why it is important to have a coordinated<br />

European approach to AI. We must develop policies<br />

that protect individuals - a human centric approach<br />

that also allows Europe to be competitive in the<br />

AI landscape. AI applications must comply with<br />

fundamental rights.”<br />

The General Data Protection Regulation already protects personal data. It<br />

is now essential to shape a framework that addresses possible challenges<br />

to human dignity, non-discrimination, equality, freedom of expression<br />

and other fundamental rights. This is why, a few weeks ago, I actively<br />

contributed to the preparation of legislation for a coordinated approach<br />

on the human and ethical dimension of AI.<br />

Regulation and development of AI must go hand in hand. Developing<br />

AI based on shared European values can be a competitive advantage as<br />

trust is a very important factor for the uptake of the development and use<br />

of new technologies. Business interests and fundamental rights converge<br />

when it comes to creating sustainable AI business models. We need the<br />

right kind of innovation. I am in favour of an approach that promotes the<br />

rollout of AI by creating legal certainty and investment stability while<br />

establishing societal acceptance and trust.<br />

EC - Audiovisual Service © European Union, 2020<br />

Commissioner Reynders at the weekly meeting of the European Commission, on December 2,<br />

2020, which discussed, among other items, the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights,<br />

the modernising of the EU justice systems and the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.<br />

El Comisario Reynders en la reunión semanal de la Comisión Europea, el 2 de diciembre de<br />

2020, en la que se debatieron, entre otros asuntos, la aplicación de la Carta de los Derechos<br />

Fundamentales, la modernización de los sistemas de justicia de la UE y la gestión de la<br />

pandemia del COVID-19.<br />

Con respecto al apoyo financiero de la UE, el mecanismo de recuperación<br />

y resiliencia es nuestro principal instrumento de recuperación de la<br />

COVID-19. Personalmente, pedí a los Estados miembros que planificaran<br />

ambiciosas reformas e inversiones en digitalización. Los Estados miembros<br />

también podrían beneficiarse de los fondos de la política de cohesión<br />

2021-2027 y del programa de Justicia.<br />

Nuestro apoyo no es solo financiero, sino que también se proporciona<br />

a través de medidas legislativas para facilitar la interoperabilidad entre<br />

los sistemas nacionales y eliminar barreras legales a la digitalización. La<br />

Comisión adoptó recientemente una propuesta legislativa sobre la gestión<br />

sostenible y el mantenimiento del sistema e-CODEX. Este sistema es<br />

un componente esencial e importante para el intercambio interoperable<br />

y seguro de información y datos entre los tribunales nacionales y las<br />

autoridades competentes en los procedimientos judiciales transfronterizos.<br />

Los Estados miembros tienen acceso gratuito a e-CODEX. A finales de este<br />

año, la Comisión tiene por objetivo presentar una importante propuesta de<br />

reforma para la digitalización de la cooperación judicial transfronteriza<br />

de la UE en materia civil, comercial y penal. Esta propuesta es un paso<br />

más en la modernización de los procedimientos de cooperación judicial<br />

y en hacerlos más eficientes y resistentes a las crisis.<br />

Confío en que la ambiciosa agenda de la Comisión y el compromiso<br />

compartido de los Estados miembros de llevar la justicia a la nueva<br />

era digital, mediante un mejor uso de las tecnologías, será en beneficio<br />

directo de nuestros ciudadanos, juristas, empresas y el estado de derecho<br />

en su conjunto.<br />

JT: La Estrategia Europea de Formación Judicial 2021-2024 hace referencia<br />

a la necesidad de potenciar la digitalización de la formación judicial y<br />

preparar a los profesionales de la justicia para que adopten la digitalización<br />

y el uso de la inteligencia artificial. ¿En qué medida la Comisión Europea<br />

de Justicia ha estado trabajando en las cuestiones del uso humano<br />

y ético de la inteligencia artificial en los sistemas de justicia penal?<br />

DR: Los servicios de Justicia de la Comisión han comenzado a trabajar en<br />

cuestiones de inteligencia artificial (IA) en el contexto de la justicia penal.<br />

Este trabajo se ha desarrollado recientemente con la adopción por parte de<br />

la Comisión de su marco general de IA. Esto está en curso, y la Comisión<br />

ha lanzado recientemente una iniciativa sobre un enfoque europeo de la<br />

inteligencia artificial. En la Dirección General de Justicia, celebramos<br />

una reunión preliminar del grupo de expertos durante la cual abordamos<br />

diversas cuestiones, como la responsabilidad penal y los aspectos de los<br />

derechos fundamentales y de la protección de datos. Una vez que se haya<br />

finalizado el marco de IA de la Comisión, tenemos previsto profundizar<br />

en nuestro trabajo sobre la IA en el contexto judicial y policial.<br />

“<br />

La IA es crucial para nuestro siglo. Puede traer<br />

grandes beneficios para la sociedad y la economía,<br />

pero también riesgos. Por eso es importante tener<br />

un enfoque europeo coordinado de la IA. Debemos<br />

desarrollar políticas que protejan a las personas, un<br />

enfoque centrado en el ser humano que también<br />

permita a Europa ser competitiva en el panorama<br />

de la IA. Las aplicaciones de IA deben cumplir con<br />

los derechos fundamentales.”<br />

El Reglamento General de Protección de Datos ya protege los datos<br />

personales. Ahora es esencial dar forma a un marco que aborde los posibles<br />

desafíos a la dignidad humana, la no discriminación, la igualdad, la libertad<br />

de expresión y otros derechos fundamentales. Por eso, hace unas semanas,<br />

contribuí activamente a la elaboración de una legislación para un enfoque<br />

coordinado sobre la dimensión humana y ética de la IA.<br />

Semester / Semestre 1 2021 JUSTICE TRENDS // 15

European Union<br />

Unión Europea<br />

JT: In her 2020 State of the Union address, President Ursula Von der<br />

Leyen announced the New European Bauhaus (NEB) as the recent<br />

European Commission initiative to lead a paradigmatic shift in lifestyle,<br />

and industrial and entrepreneurial activity in response to mounting climate<br />

and environmental threats. The new initiative aims to stimulate public and<br />

business mindsets to life, work, and building concepts based on sustainability,<br />

inclusiveness, aesthetics, quality of experience, protecting the climate<br />

and preserving biodiversity. The whole idea revolves around community,<br />

accessibility, circularity, affordability, simplicity, creativity, art, culture<br />

experimentation, connection, togetherness and socio-economic and gender<br />

equality. The European Commission highlights the purpose of a living<br />

movement.<br />

How do you envisage the involvement of the justice sector in the<br />

New European Bauhaus initiative – how do you see the NEB’s main<br />

concepts (of beauty, sustainability and togetherness) being applied<br />

to justice systems across the EU, including prison and probation<br />

administrations?<br />

DR: The New European Bauhaus (NEB) is the Commission’s creative<br />

and interdisciplinary movement. It aims to bring citizens, experts,<br />

businesses, and institutions together and facilitate conversations about<br />

making tomorrow’s living spaces more affordable and accessible. It is a<br />

plan for the future, and we are only at the early stages.<br />

The NEB will highlight the value of simplicity, functionality, and circularity<br />

of materials without compromising the need for comfort and attractiveness<br />

in our daily lives. It will provide financial support to innovative ideas<br />

and products through ad hoc calls for proposals and through coordinated<br />

programmes included in the long-term EU budget.<br />

The approach will be one of social inclusion: nobody left behind, removal<br />

of barriers faced by people, improving living conditions for all citizens.<br />

I can see how this approach would be attractive to architects and designers<br />

of prisons and other public justice buildings (such as courts and police<br />

stations) which have traditionally been functional and sometimes grim.<br />

There are some notable exceptions, such as the magnificent new court<br />

building in Antwerp, which has environmental features as well as an<br />

emphasis on transparency.<br />

The NEB movement will make funds available and will offer prizes to<br />

create incentives for designers of public buildings who incorporate the<br />

principles of sustainability, inclusion and aesthetics into their concepts. //<br />

La regulación y el desarrollo de la IA deben ir de la mano. El desarrollo<br />

de la IA basada en valores europeos compartidos puede ser una ventaja<br />

competitiva, ya que la confianza es un factor muy importante para la<br />

adopción del desarrollo y el uso de nuevas tecnologías. Los intereses<br />

empresariales y los derechos fundamentales convergen cuando se trata<br />

de crear modelos de negocio de IA sostenibles. Necesitamos el tipo<br />

de innovación adecuado. Estoy a favor de un enfoque que promueva<br />

el despliegue de la inteligencia artificial al crear seguridad jurídica y<br />

estabilidad de la inversión, al tiempo que establece la aceptación y la<br />

confianza de la sociedad.<br />

JT: En su discurso sobre el estado de la Unión de 2020, la Presidenta<br />

Ursula Von der Leyen anunció la Nueva Bauhaus Europea (NEB, por<br />

sus siglas en inglés) como la reciente iniciativa de la Comisión Europea<br />

para liderar un cambio paradigmático en el estilo de vida y la actividad<br />

industrial y empresarial en respuesta a las crecientes amenazas climáticas<br />

y medioambientales. La nueva iniciativa tiene como objetivo estimular la<br />

mentalidad del público y de las empresas a los conceptos de vida, trabajo<br />

y construcción basados en la sostenibilidad, la inclusión, la estética, la<br />

calidad de la experiencia, la protección del clima y la preservación de<br />

la biodiversidad. Toda la idea gira en torno a comunidad, accesibilidad,<br />

circularidad, asequibilidad, simplicidad, creatividad, arte, experimentación<br />

cultural, conexión, unión e igualdad socioeconómica y de género. La<br />

Comisión Europea destaca el propósito de un movimiento vivo.<br />

¿Cómo prevé la participación del sector de la justicia en la iniciativa<br />

Nueva Bauhaus Europea? ¿Cómo cree que se aplican los principales<br />

conceptos de la NEB (de belleza, sostenibilidad y unión) a los sistemas<br />

judiciales de toda la UE, incluidas las administraciones penitenciarias<br />

y de libertad condicional?<br />

DR: La Nueva Bauhaus Europea (NEB) es el movimiento creativo e<br />

interdisciplinario de la Comisión. Su objetivo es reunir a ciudadanos,<br />

expertos, empresas e instituciones y facilitar las conversaciones sobre<br />

cómo hacer que los espacios de vida del mañana sean más asequibles<br />

y accesibles. Es un plan para el futuro, y solo estamos en las primeras<br />

etapas. La NEB destacará el valor de la simplicidad, la funcionalidad y la<br />

circularidad de los materiales sin comprometer la comodidad y el atractivo<br />

en nuestra vida diaria. Proporcionará apoyo financiero a ideas y productos<br />

innovadores mediante convocatorias de propuestas ad hoc y mediante<br />

programas coordinados incluidos en el presupuesto de la UE a largo plazo.<br />

El enfoque será de inclusión social: nadie se quedará atrás, se eliminarán<br />

las barreras a las que se enfrentan las personas, y mejorarán las condiciones<br />

de vida de todos los ciudadanos. Puedo ver cómo este enfoque sería<br />

atractivo para los arquitectos y diseñadores de prisiones y otros edificios<br />

de justicia pública (como tribunales y comisarías) que tradicionalmente<br />

han sido funcionales y, a veces, sombríos. Hay algunas excepciones<br />

notables, como el magnífico nuevo edificio de la corte en Amberes, que<br />

tiene elementos ambientales destacados y un énfasis en la transparencia.<br />

El movimiento NEB pondrá a disposición fondos y ofrecerá premios para<br />

crear incentivos para los diseñadores de edificios públicos que incorporen<br />