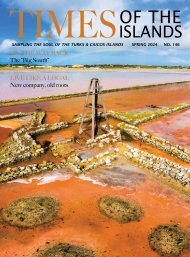

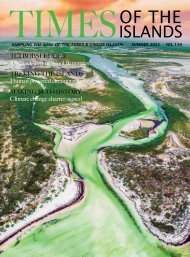

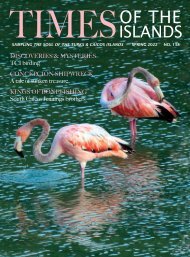

Times of the Islands Spring 2023

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, real estate, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, real estate, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

green pages newsletter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> department <strong>of</strong> environment & coastal resources<br />

At first I wondered if I was looking at some kind <strong>of</strong><br />

garbage, or perhaps <strong>the</strong> remnants <strong>of</strong> some long-lost civilization.<br />

I later learned I’d stumbled upon 925 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

largest Reef Balls in <strong>the</strong> world, each nearly as tall as I<br />

am and weighing around 5,000 pounds. These aren’t <strong>the</strong><br />

only artificial reef structures to have been built in <strong>the</strong><br />

Turks & Caicos—over <strong>the</strong> last three decades, countless<br />

Reef Balls have popped up all over TCI to create new coral<br />

habitat and aid existing natural reefs.<br />

Reef Balls were news to me, but <strong>the</strong> plight <strong>of</strong> coral<br />

worldwide was not. Reefs everywhere have been struggling<br />

under various (mostly anthropogenic) stresses:<br />

overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, climate<br />

change. Nearshore reefs are under even more pressure<br />

from hundreds <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> tourists each year, who<br />

cause inadvertent damage by standing on corals, leaving<br />

behind trash, or wearing toxic sunscreen.<br />

The loss <strong>of</strong> our reefs would be a tragedy to anyone<br />

who, like me, has experienced <strong>the</strong> wonder <strong>of</strong> watching<br />

fish in <strong>the</strong>ir natural habitat through a pair <strong>of</strong> snorkel goggles.<br />

But sadly, if humans cause reefs to go extinct, that<br />

would be <strong>the</strong> least <strong>of</strong> our worries. Reefs buffer coastlines<br />

from storms, provide jobs through fishing and tourism,<br />

and support thousands <strong>of</strong> species <strong>of</strong> fish, many <strong>of</strong> which<br />

are key sources <strong>of</strong> food for coastal communities. Losing<br />

coral reefs would mean losing food, income, and protection<br />

for roughly half a billion people—including many in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Turks & Caicos. It is clearly in our best interest, not<br />

just Mo<strong>the</strong>r Nature’s, to do what we can to protect coral<br />

reefs. The Reef Balls are one <strong>of</strong> several ways scientists are<br />

tackling this challenge.<br />

While I was excited to see <strong>the</strong>se Reef Balls in action,<br />

I was also curious. As a former materials engineer,<br />

I’m familiar with <strong>the</strong> harshness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> marine environment.<br />

Few materials can withstand <strong>the</strong> corrosive salt<br />

water for long; most will start to disintegrate after a few<br />

years, leaching chemical and particulate pollution into<br />

<strong>the</strong> ocean. Seeing <strong>the</strong> vast rows <strong>of</strong> Reef Balls outside<br />

Malcolm’s Road Beach, I wondered how <strong>the</strong>y were built<br />

to help <strong>the</strong> environment without causing more harm. The<br />

answer turned out to be a relatively simple design—but it<br />

took a few decades to figure out.<br />

Although ancient hunters experimented with <strong>the</strong><br />

first artificial reefs as a way <strong>of</strong> luring more fish to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

nets, using <strong>the</strong>m for eco-friendly purposes was mostly<br />

a 20th-century idea. People started to notice how shipwrecks<br />

evolved into flourishing man-made reefs, and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

got <strong>the</strong> idea to kill two birds with one stone by dropping<br />

garbage into <strong>the</strong> ocean.<br />

Florida’s Osborne Reef is a prime example: In <strong>the</strong><br />

1970s, a huge effort was undertaken to “recycle” over<br />

a million car tires by turning <strong>the</strong>m into coral habitat.<br />

Unfortunately, what was meant to become <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

longest artificial reef ended in ecological disaster. We<br />

learned <strong>the</strong> hard way that reefs couldn’t be built from<br />

just anything. Tire rubber, for example, doesn’t have <strong>the</strong><br />

right surface texture to allow coral larvae to attach, and<br />

it’s too lightweight to stay in place over many years. All<br />

<strong>the</strong> tires managed to grow was algae, and <strong>the</strong>y floated<br />

away after <strong>the</strong> first storm, creating a massive pollution<br />

problem that’s still being cleaned up 50 years later.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong>n, scientists have learned how to build successful<br />

artificial reefs. This means using marine-safe<br />

materials that can stand <strong>the</strong> test <strong>of</strong> time in salt water,<br />

such as steel (what most shipwrecks are made <strong>of</strong>), glass,<br />

and cement. Dumping glass bottles and cinderblocks<br />

won’t work—<strong>the</strong>se structures must be large and heavy<br />

enough to prevent movement during storms. They must<br />

have enough surface texture to promote coral attachment,<br />

and enough nooks and crannies to encourage fish<br />

to take shelter.<br />

The Reef Balls, devised by <strong>the</strong> Reef Ball Development<br />

Group, are made from concrete with a pH similar to seawater,<br />

which prevents <strong>the</strong> balls from decaying. They’re<br />

expected to last 500+ years underwater! The concrete’s<br />

texture and chemical makeup mimic natural coral limestone,<br />

making it an ideal place for coral to attach and<br />

grow. It’s also easy to mold into <strong>the</strong> shapes needed for<br />

a successful artificial reef. Reef Innovations built and<br />

installed all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Reef Balls around TCI, including <strong>the</strong><br />

aptly named “goliath” model at Malcolm’s Road Beach.<br />

They make many o<strong>the</strong>r sizes and shapes <strong>of</strong> concrete<br />

reef structures, some as small as nine inches high—but<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir weight distribution keeps <strong>the</strong>m in place even during<br />

storms, and <strong>the</strong>ir hole patterns are designed so that<br />

rough seas actually push <strong>the</strong> Reef Balls fur<strong>the</strong>r into <strong>the</strong><br />

sand.<br />

Some Reef Balls are installed with coral fragments<br />

transplanted from imperiled reefs. O<strong>the</strong>rs rely solely on<br />

“natural recruitment,” meaning <strong>the</strong>y bide <strong>the</strong>ir time on <strong>the</strong><br />

sea floor until coral larvae, drifting past in <strong>the</strong> current,<br />

latch on. Natural recruitment is understandably a slower<br />

<strong>Times</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Islands</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2023</strong> 37