Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

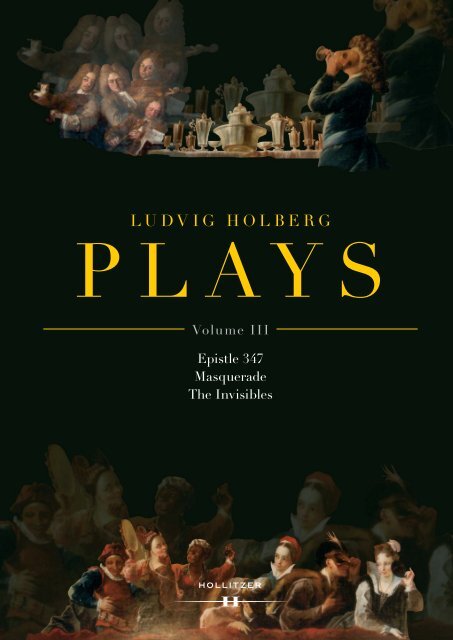

LUDVIG HOLBERG<br />

PLAYS<br />

<strong>Vol</strong>ume <strong>III</strong><br />

Epistle 347<br />

Masquerade<br />

The Invisibles<br />

I

LUDVIG HOLBERG<br />

PLAYS<br />

VOLUME <strong>III</strong>

LUDVIG HOLBERG<br />

PLAYS<br />

VOLUME <strong>III</strong><br />

EPISTLE 347<br />

MASQUERADE<br />

THE INVISIBLES<br />

Edited and translated from the Danish by<br />

Bent Holm and Gaye Kynoch

The translation project is grateful for funding from:<br />

Danish Arts Foundation<br />

Frontcover image, details from:<br />

Benoit Le Coffre, A Masquerade, Frederiksberg Palace, Denmark, 1704<br />

Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume <strong>III</strong><br />

Epistle 347; Masquerade; The Invisibles<br />

Edited and translated from the Danish by Bent Holm and Gaye Kynoch<br />

Vienna: HOLLITZER VERLAG, 2023<br />

Epistle 347 (Epistel 347), Masquerade (Maskerade), and The Invisibles (De Usynlige)<br />

have been translated from the Danish versions published by Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>s Skrifter<br />

(The Writings of Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>) at:<br />

Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>s Skrifter http://holbergsskrifter.dk<br />

Cover and Layout: Nikola Stevanović<br />

Printed and bound in the EU<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of<br />

this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by<br />

any means, digital, electronic or mechanical, or by photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or<br />

conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without prior written permission of the publisher.<br />

Responsibility for the content and for questions of copyright lies with the editors.<br />

Performance rights: All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application for<br />

performance rights of any nature should be made before rehearsals to Hollitzer Verlag.<br />

No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained.<br />

www.hollitzer.at<br />

ISBN 978-3-99094-170-6

CONTENTS<br />

7<br />

PREFACE<br />

15<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Epistle 347<br />

(Epistel 347)<br />

17<br />

EPISTLE 347<br />

1749<br />

21<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Masquerade<br />

(Maskerade)<br />

23<br />

MASQUERADE<br />

1723/24<br />

97<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Invisibles<br />

(De Usynlige)<br />

99<br />

THE INVISIBLES<br />

1726<br />

5

6

PREFACE<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> and masks<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> saw the world, human existence, as a stage upon which the actors, humankind,<br />

appear clad in a character trope, a mask, a manifestation of the surrounding<br />

cultural reality – but not necessarily a manifestation of any deeper truth about<br />

humankind or about the world; each individual comprises numerous identities,<br />

interpreted in a multitude of ways via the multitude of responding individuals in<br />

any given situation. In this theatrum mundi – the theatre of life – it is important to<br />

act professionally: not taking the rules of the ‘societal game’ at face value while<br />

being able to fake it convincingly, as and when necessary. Ultimately, this view<br />

of human existence implies striking a balance between substance and appearance.<br />

What is what? When is the mask an augmentation and when is it an empty shell?<br />

As <strong>Holberg</strong> wrote in one of his philosophical essays: “Most people are masked<br />

and, like performers, clad themselves as different figures for as long as the performance<br />

lasts. Only when the role has been played, and the mask removed, do we<br />

know whether it has been feigned or genuine.” 1 The unmasking – be it the finale<br />

of a play or the finale of a life – is therefore a philosophical and creative moment<br />

of truth.<br />

Given that illusion and roleplay are such stuffs as theatre is made on, the stage<br />

is <strong>Holberg</strong>’s perfect instrument upon which to act out the existential themes.<br />

When religious influences caused theatre to be, in practice, banned in Denmark<br />

for two whole decades (see Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume I, pp. 11–15), opening<br />

again in 1747, he turned particularly to the medium of philosophical essay, often<br />

with stage performance or masquerade entertainment as metaphorical backdrop<br />

to these philosophical thoughts. A dialogue thus emerges between his plays and<br />

his moral reflections; they elaborate, clarify and modify one another.<br />

The first two volumes in the present series of new English-language translations<br />

highlight the roles of, respectively, theatre and women, in which <strong>Holberg</strong><br />

challenges and subverts fixed notions and patterns of response. It could be said<br />

that he unmasks the sightlines and reveals how views of class and gender, for<br />

example, are more a matter of conventions and social structures than of actual<br />

matter.<br />

For this volume, we have chosen to present <strong>Holberg</strong>’s constantly underlying<br />

mask theme via three pieces written in various styles and forms, crisscrossing<br />

one another while drawing the major points into the individual scenarios and the<br />

1 Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: Moralske Tanker (‘Moral Reflections’), Libr. I, Epigr. 117, Copenhagen 1744,<br />

p. 184.<br />

7

overall picture. In these three pieces, <strong>Holberg</strong> has pinpointed vital elements of<br />

la comédie humaine, the human comedy, the complexity of human civilisation and<br />

human endeavours.<br />

To <strong>Holberg</strong>, the mask was both an instrument of performance and a metaphor.<br />

It is no surprise that the first experience of theatre to make an impression on him,<br />

according to his own words, was the Italian commedia dell’arte, which he encountered<br />

during carnival in Rome, where he stayed 1715–1716. In 1722, a new theatre<br />

opened in Copenhagen; for the first time, plays were performed professionally in<br />

Danish, the main focus being on satirical depictions of contemporaneous realities.<br />

An underlying inspiration, however, was generated by the ironic commedia dell’arte<br />

gaze upon the world. Masks were indeed a central component in another activity<br />

at the theatre, and a source of its income: the public masquerades. When these too<br />

were subject to an official ban, <strong>Holberg</strong> saw his opportunity to present a whole<br />

slew of arguments in defence of the masquerade; arguments that essentially address<br />

the relationship between nature and culture.<br />

When the new theatre had opened, disapproved of by theological and academic<br />

authorities, <strong>Holberg</strong> had argued (under the guise of a man named Just Justesen,<br />

in his Reflections on Theatre; see Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume I, pp. 11–21) that<br />

it was not the thing-in-itself – in casu the theatre – but the thing-as-seen that<br />

determined whether it was offensive or acceptable. If the clergy and the authorities<br />

were cheerfully frequent attendees of the theatre – as was the case in other countries<br />

– well then, theatre would magically cease to symbolise all things shady and<br />

offensive. In the wider perspective, it could be said that theatre actually exposes<br />

the theatricality of everyday and public life. <strong>Holberg</strong>’s argument suggested that<br />

the masquerade served a higher purpose by unmasking the roleplay and playacting<br />

in the private sphere and in the societal arena.<br />

The twofold masquerade<br />

In the play Masquerade (1723/24; Maskerade), moderately-minded Mr Leonard<br />

speaks in defence of this vilified form of entertainment when he refers to the “natural<br />

equality” between people that can be acted out in the forum of the masquerade.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> here references nature as the ultimate yardstick – as is also the case with<br />

equality between men and women (see Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume II, pp. 9–17).<br />

In ‘Epistle 347’ (1749; ‘Epistel 347’), he reiterates that we are dealing with the<br />

original “human state” of equality between people, but adds an extra layer by<br />

qualifying this as: “to which humankind was assigned by God at first creation,<br />

and from which through sin is fallen”. God and nature are the ultimate heavyweights<br />

when ‘the natural state’ is being written into a biblical frame narrative –<br />

perhaps in this instance with due consideration to the pietistic situation prevailing<br />

8

in Denmark at the time. But he goes even further by putting the issue of equality<br />

into a history of civilisation context, turning the relationship between reality and<br />

masquerade upside down. Because now, paradoxically, it turns out that what we<br />

believe to be reality is in reality a masquerade, while the masquerade is more real<br />

than reality since it unmasks the masquerade of reality! Civilisation is in effect<br />

a Fall from the original, natural state, an arena in which a ‘philosophical game’<br />

displays – or unmasks – the irrationality of the cultural playacting. The mask liberates<br />

the individual from the process of masking imposed by the conventions of<br />

everyday life. This unmasking via masking corresponds, as mentioned, to theatre<br />

exposing the theatricality of its surrounding culture.<br />

In ‘Epistle 347’, <strong>Holberg</strong> sums up this idea: “the conventional human state in<br />

which we live is a constant masquerade, since social order, conventions and customs<br />

impose masks upon us, which in this kind of amusement we lay aside, as it<br />

were, and strictly speaking we are not truly masked except when bare faced.” The<br />

situation that follows on from the natural state is defined on the basis of hierarchies<br />

and conventions and is thus in some sense illusory – roleplay as applied to,<br />

for example, gender and class – and our conventional life is therefore “a constant<br />

masquerade”. A great many aspects of human civilisation that are viewed with<br />

profound seriousness are accordingly, seen in this perspective, fundamentally<br />

meaningless – form without substance, pure show: ‘theatre’.<br />

The mask plays a twofold – or, rather, complementary – role: liberator of<br />

pre-civilisational reality, which is an inner truth, and indicator of civilisational<br />

pretence, which is an outer form.<br />

The dialectical gaze<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong>’s view of humankind and nature is not, however, romanticising. His assessment<br />

of humankind is twofold: potentially socially-minded and potentially<br />

selfish. And the natural state involves, as mentioned, a constructive chaos, an<br />

original authenticity, which convention and culture distort by adding a layer of<br />

stage managing and status ranking, which is then attributed a significance it does<br />

not have – but where the mask provides an opening for insight into deeper truths.<br />

The natural state can also, however, be read as a destructive chaos, a concoction<br />

of instinctual urges that culture must bring under control and discipline in order<br />

to avoid the ultimate massacre erupting and taking over. <strong>Holberg</strong> also inserts the<br />

latter reading into a biblical frame narrative. Given that the pure natural state<br />

is charged with “sin and wickedness”, human behaviour had to be speedily subject<br />

to system and order as safeguard against violation. “We can also see that the<br />

natural state did not last long; because we find kingdoms and societies established<br />

soon after the Flood; so the oldness of governance shows the brevity of the natural<br />

9

state.” 2 But when the civilising process degenerates into empty manifestations, artificial<br />

inequalities and inflexible authorities, then the culture acts as anti-nature<br />

and thus obstructs constructive dynamism in society.<br />

Underlying the picture, however, madness features as a quite fundamental<br />

aspect of the world and reality; due to its lack of usefulness, this madness has its<br />

own stimulating, provocative utility value, which <strong>Holberg</strong> praises in one of his<br />

philosophical essays: “For my part, I would not care to live in a country where<br />

there were no fools. For a fool has the same effect in a civil society as gastric acid<br />

has in a person’s stomach. It is like an efficacious sal volatile that agitates blood<br />

and bodily fluids – indeed, it can be compared with a stormy wind, which, although<br />

it sometimes demolishes houses and tears down trees, also purges the air,<br />

impedes putrification and thwarts maladies generally arising from far too much<br />

tranquillity.” 3<br />

The madness involves an activating and cleansing power. Mask and stage alike<br />

account for this form of metaphorical gastric acidity, pervading the role played by<br />

the fool and the madness in society.<br />

Masquerade is traditionally read as a totally unambiguous dispatch, a one-sided<br />

defence of happy and upbeat youth in the face of grumpy and downbeat adulthood.<br />

But the masquerade is in no way romanticised. The play can just as well be<br />

read as a depiction of a young man who has become hooked on an entertainment<br />

that prevents him from fulfilling his duties. When the necessity of madness and<br />

the reality of the natural state come into play, with the masquerade as the heart<br />

and Henrik as the pivotal point, then the dialectics and the complementarity come<br />

into their own. <strong>Holberg</strong> wields a mischievous pen. A production that respects this<br />

ambiguity will stimulate and involve the audience in the playacting on stage.<br />

It all revolves around the ironically down-to-earth gaze upon the world.<br />

Around distinguishing illusion from reality, the shell from the kernel, the shadow<br />

from the object – as <strong>Holberg</strong> states time and again in plain reference to Plato and<br />

his iconic allegory about mistaking fiction for substance: a group of people live in<br />

a cave, they believe that the shadows projected onto the wall are reality. Henrik,<br />

however, is somewhat more clear-sighted than the other characters in the play. It<br />

is no accident that he is the one to conclude in the final scene: “Then a play has<br />

been played out here.”<br />

A mask betrayed<br />

Henrik is <strong>Holberg</strong>’s abrasive version of the commedia dell’arte stock Harlequin figure;<br />

he is unsentimental, his feet are firmly planted on matter-of-factly sensible<br />

2 Ibid. Libr. <strong>III</strong>, Epigr. 41, p. 452.<br />

3 Ibid. Libr. I, Epigr. 86, p. 128.<br />

10

ground. Harlequin’s words and actions challenge the ‘serious’ surrounding environment,<br />

its passions and emotions. He represents a ‘grotesque’ perception of the<br />

world. <strong>Holberg</strong> was familiar with this character from the Italian-French theatre in<br />

Paris, reading their scenarios from which he merrily ‘borrowed’ situations and<br />

wordplay. The Kilian figure in Ulysses von Ithacia is shaped on this Harlequin (see<br />

Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume I). The harlequinade represents a constructive chaos,<br />

one which defies cast-iron values, categories and hierarchies. It is a form of madness,<br />

which is essential if society is to be prevented from stagnating in self-affirmation,<br />

a lack of respect that we see in Henrik when he sabotages inflexible Jeronimus’s<br />

authority and tests Leander’s enamoured feelings. This is Harlequin’s function. It<br />

is his character. And it is writ large in his mask.<br />

When financial difficulties obliged the new Danish theatre to close temporarily<br />

in 1725, <strong>Holberg</strong> took the opportunity to visit Paris. He went to the theatre<br />

that had been a main inspiration, along with the works of Molière, for his playwriting<br />

pen and its satirical take on his day and age. <strong>Holberg</strong> contacted the leader<br />

of the Italian theatre, hoping to arouse interest in his Danish plays. His hopes<br />

were not fulfilled. New winds were blowing, carrying a more moral-emotionalromantic<br />

drift that was a world away from the robustly disrespectful comedy that<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> considered to be the raison d’être of the theatre stage. The sophisticated,<br />

refined, emotional Harlequin he encountered in Paris filled him with frustrated<br />

anger. To <strong>Holberg</strong>’s mind, this character was absolutely not Harlequin, quite the<br />

opposite, he was an artless dope of the kind who could be easily hoodwinked. His<br />

characteristic of the ‘new’ Harlequin quivers with indignant sarcasm. The devilmay-care<br />

attitude manifested by the real harlequinade had been watered down<br />

into sentimentality: “In our day, a substantial restriction has occurred in the liberty<br />

of speech we so admired from the old Italian troupe, and which in Louis<br />

XIV’s time was the soul of this theatre.” 4<br />

Bitter over being rejected and angry that Harlequin was being betrayed, once<br />

back home <strong>Holberg</strong> wrote The Invisibles (1726; De usynlige). In the first part of the play,<br />

Harlequin is in harmony with his mask: witty, prosaic, robust. Thereafter, he abandons<br />

his character and takes robust strides away from his role as ‘true’ Harlequin,<br />

but with the paradoxical twist that no matter how infected he becomes by the<br />

amorous-erotic sport, his mask stays firmly in place. A clear-cut split is visible on<br />

stage: the mask is saying one thing, the character’s behaviour is saying something<br />

else entirely. The two sides are mutually contradictory. That is not going to end<br />

well. The person designated to bring him quite literally to his senses is Columbine,<br />

representative of healthy sensuality, the woman he has abandoned. His offence is<br />

devastating – as is his ‘cure’. Having been threatened with physical violence, he<br />

4 Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>, Ad virum perillustrem *** epistola (Første levnedsbrev), Copenhagen 1728, p. 179<br />

(various translations as versions of ‘Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>’s Memoirs’).<br />

11

eventually submits utterly to female supremacy. Such are the extremes awaiting<br />

anyone who releases their grip on reality and surrenders to affectations.<br />

Through his betrayal, Harlequin has thrown in his lot with convention, the<br />

staging of life, which in the perspective of the masquerade is the opposite of nature.<br />

He has betrayed his role – i.e. his mask – and abandoned himself to a masquerade.<br />

Henceforth, Columbine takes control.<br />

The greater the difficulty, the greater the value<br />

The Invisibles is not only about Harlequin. A love story between two young aristocrats<br />

is also played out, and is done so in remarkably sensitive psychological tones<br />

on their own thoroughly genuine terms (just like the besotted couple in Masquerade),<br />

while enacting themes that go beyond the characters’ sensitive emotional shifts.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> is here again (and as he would again twenty-five years later in the ‘Epistle’)<br />

articulating radical reflections that give philosophical or existential perspective<br />

to the issues presented in a play, while introducing light and shade into the picture<br />

of romantic love.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> is again turning hierarchies and conventions upside down. In one of<br />

his philosophical essays, he refers with appreciation and respect to the peasantry,<br />

“the lowest of all”. Unlike the sophisticated processes applied by the aristocracy<br />

in order to enter couple relationships – which are: “a kind of play. Four Acts have<br />

to be acted out before you reach the conclusion, which is the content of the fifth<br />

Act” – <strong>Holberg</strong> writes that: “A young peasant’s courtship, however, is without<br />

all these formalities: it all happens in an orderly and natural fashion. Each of the<br />

lovers is without mask; they settle on the price themselves […] for which reason,<br />

such marriages have better outcomes than those made with artfulness.” 5 The philosopher<br />

is using the terminology of the dramatist when he depicts the ‘natural’<br />

couple as being without mask – and thus without the civilisational artificiality.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> makes it clear that the significance or value of a phenomenon is not<br />

necessarily something it has but something it is ascribed – as we have also seen<br />

with theatre and masquerade. And that is not all: the higher the price, the greater<br />

the difficulty involved in acquisition, then the greater the value or significance<br />

ascribed. In another essay, he discusses the psychological mechanism: the more<br />

expensive and unattainable, the more attractive. If something is rare and costly,<br />

however, then people disdain “the things that nature has characterised by goodness,<br />

simply because they are available without effort and expense, and on the<br />

other hand find delight in unnatural and ill-tasting things simply because they are<br />

expensive and cannot be acquired without difficulty.” 6<br />

5 Moralske Tanker, Libr. I, Epigr. 36, pp. 235–236.<br />

6 Ibid., Libr. II, Epigr. 2, p. 283.<br />

12

In The Invisibles, Harlequin chokes on the apple allegory: how attractive apples<br />

hanging on a tree seem in contrast to the apples that can simply be picked up from<br />

the ground. The Invisible uses this apple metaphor to make Leander understand<br />

that it is only by controlling his desire that he will be able to demonstrate whether<br />

his feelings are unshakable or unsound. This is the exact image that <strong>Holberg</strong> now<br />

uses in the essay, in this case as an example that the ‘Romanesque’ manner of wooing<br />

can also be a matter of strategy – a tactic Columbine adopts to great effect.<br />

“An apple, lying on the ground,” he writes, “is bypassed, and you climb up to the<br />

top of the tree to pick off another one, which often, although not as ripe, tastes<br />

better, given that it has taken effort to pick it. A maiden, who willingly offers her<br />

service or surrenders unconditionally at the first charge, cools the wooer’s love.<br />

For this reason, a cunning woman gives the impression of cool-headedness, puts<br />

up a resistance, and lets a suitor woo in the Romanesque way, thereby to increase<br />

his ardour, and more surely to achieve her wish […] Difficulty increases desires,<br />

and a hundred cunning measures are used to storm the fortresses that are most<br />

fortified.” 7<br />

Mid discussion, <strong>Holberg</strong> notes that: “The human being is herein, as in other<br />

respects, curious and incomprehensible.” 8 This thought is a continuation of the<br />

conclusion to a satirical poem he had written a good twenty years earlier: “For in<br />

each individual there is a curious chaos” 9 for which reason we can neither define<br />

nor comprehend humankind. Humankind is a concoction of incompatible components,<br />

an unending gamut of potential identities.<br />

The Invisibles puts these themes through a kaleidoscopic mill, without proclaiming<br />

any clear-cut ‘solutions’ – with the one exception: Harlequin’s betrayal<br />

of his mask’s mission is shown no mercy.<br />

Identity and masks<br />

The mask is a straightforward manifestation of the character and thereby the identity,<br />

the self. But when <strong>Holberg</strong> suggests that we are only wearing masks when<br />

we have bare faces, identity becomes a variable concept – and here the Italian<br />

playwright Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936) inevitably enters the picture. Pirandello<br />

revolutionised modern theatre through his questioning of identity. He even gave<br />

his collection of plays the title Maschere nude (literally: ‘naked masks’), on exactly<br />

the same wavelength as the <strong>Holberg</strong>ian paradox. A play such as Pirandello’s Sei<br />

personaggi in cerca d’autore (1921; Six Characters in Search of an Author) is structured<br />

7 Ibid., pp. 286–287.<br />

8 Ibid., p. 288.<br />

9 Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>, Apologi for sangeren Tigellius (‘Apology for the Bard Tigellius’) in Fire skæmtedigte<br />

(‘Four Jestful Poems’), Copenhagen 1722, p. c3r.<br />

13

around the interactions between the individual’s inner ‘curious’ chaos and the<br />

interpretative gaze of the surrounding world; the fictitious ‘characters’ of the title<br />

insist on being more real than the ‘real’ characters in the play.<br />

In another essay, <strong>Holberg</strong> pens a portrait of himself, one that does not match<br />

up – simply because it is seen from the vantage point of other people, and they<br />

draw conclusions from isolated, momentary encounters. They see, so to speak,<br />

just the one mask. <strong>Holberg</strong> is miserly. He is generous. He is lazy. He is hard-working.<br />

He loves women. He is a misogynist. He is cheerful. He is gloomy, and so on and<br />

so forth, so that: “when someone cannot conceive how the characteristics both<br />

can be correct and incorrect, then you can ask them to turn the page.” Only when<br />

seen from one selective vantage point does identity appear to have a core and the<br />

world to add up. But this is not the case. In a nutshell: “there is nothing I study<br />

more and yet comprehend less than my self.” 10<br />

Masks too – also in a nutshell – can be supplied with multiple meanings in<br />

the <strong>Holberg</strong>ian universe. In this current selection of new translations, for example,<br />

the mask is linked to the masquerade as image of an original state. It can<br />

represent anarchy as corrective of obduracy in social matters. Or it can create a<br />

fictitious identity. Masquerade, madness, theatre – all attack conventions as controlling<br />

factors in the perception of identity, gender and class. The more complex<br />

implications come to fruition when <strong>Holberg</strong>’s analytical essays are drawn into the<br />

picture, and, ultimately: in production, the play performed on stage, trusting the<br />

script, the wit and the reflections, and trusting the audience – <strong>Holberg</strong>’s plays are<br />

not purely for comedic pleasure, they are magical studies of the ongoing human<br />

condition.<br />

Bent Holm & Gaye Kynoch<br />

Copenhagen, Denmark 30.7.2023<br />

10 Epistel 257 (‘Epistle 257’) in Epistler <strong>III</strong> (‘Epistles <strong>III</strong>’), Copenhagen 1750, pp. 339 and 333.<br />

14

INTRODUCTION<br />

EPISTLE 347<br />

(EPISTEL 347)<br />

Published 1749 in Epistler IV (‘Epistles, <strong>Vol</strong>ume 4’)<br />

In addition to his work as historian, satirist and dramatist, <strong>Holberg</strong> was also<br />

a prolific essayist. Between 1748 and 1754, he published five volumes of short<br />

texts dealing with various, in the words of the title page, “historical, political,<br />

metaphysical, moral, philosophical and indeed droll matters”. These short essays<br />

are written in the form of ‘letters’ to a fictitious recipient: an ongoing, amicable<br />

dialogue for solo voice, responding to the supposed sendee’s views, requests for<br />

advice, enquiries, reflections on subjects they have been reading about, and so<br />

forth, always concluding with a “I remain, &c”. These ‘letters’ cover all manner<br />

of topics – from theodicy to English parliamentarism, from war to fashion, the art<br />

of fencing, the art of catching flies, Chinese theatre, deism, tolerance in matters<br />

of faith, coffee vs. tea, Islam vs. Christianity, dogs vs. cats, the potential threat<br />

from Russia, religious open-mindedness, and so on and so forth – all in all, well<br />

over 500 essays. From time to time, the ‘epistles’ also discuss quite controversial<br />

subjects in an elegant and witty tone, embedding the strong points being made in an<br />

entertaining and above all readily accessible form. <strong>Holberg</strong> the academic despised,<br />

with all his heart, academic pomposity and pedantry. As a good Socratesian, he<br />

deploys irony and paradox to lure his reader onto thin ice with seemingly extreme<br />

claims – such as suggesting that the popular masked entertainments, the masquerades,<br />

should be interpreted as a “philosophical amusement”. Epistle 347 relates closely<br />

to its writer’s comedic play Maskerade (‘Masquerade’, 1724, this volume pp. 21–96),<br />

written a quarter of a century earlier in defence of this masked “amusement”,<br />

which was very much an ingredient in the workings of the theatre building in<br />

which the play itself was to be performed; in 1724, however, the authorities banned<br />

public masquerades. The epistle even calls the servant in the play Masquerade as a<br />

witness for the defence of masquerades. The lengthy period of pietistic influence<br />

over Danish affairs, which had led to the uncompromising disapproval of theatre<br />

performances and masque players, had come to an end two years before the epistle<br />

was written, but public masquerades continued to be banned until 1768. For<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> to rekindle the masquerade theme in one of his epistles, unambiguously<br />

moving it into his philosophical-dialectic reasoning, tells us that the play was more<br />

than simply a bold shot in the arm to help out the theatre now that one source of<br />

15

evenue had dried up. In brief, the essay is about usage and significance; and, in a<br />

slightly wider perspective, about nature and culture. Excessive usage of anything<br />

– be it something as harmless as barley-flour porridge! – can cause harm. But<br />

if intelligently managed and identified for what it is, then the masquerade is an<br />

intelligent invention. On one side, <strong>Holberg</strong> operates with nature, i.e. primordial<br />

conditions; on the other side, he operates with frameworks drawn up by convention<br />

and culture, i.e. hierarchies, categories and ceremonies, which are at best hollow<br />

enactments and at worst unquestionably inconsistent with nature. As an example<br />

of the latter, <strong>Holberg</strong> addresses the relationship between the sexes: nature has<br />

created men and women as equals; that men per definition take precedence over<br />

women is contrary to nature and should be resolutely quashed.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> associates the masquerade with a primordial condition – the natural<br />

condition – that is in itself characterised by equality between human beings. He<br />

practically formulates a mythology by relating the arbitrary and artificial breach<br />

– also known as culture or civilisation – to a Fall from which the masquerade<br />

momentarily grants immunity while reflecting a pre-Fall condition. Being the<br />

good dialectician, <strong>Holberg</strong> also adopted the opposite view, in which the natural<br />

condition involves the risk of a free-for-all, the ultimate prospect of which is a<br />

scene of total carnage. Culture was thus a necessary regulating parameter, represented<br />

by a power centre designed to curb the threat of chaos and install a functional<br />

social structure. The point, however, is that this must operate on terms stipulated<br />

by nature and reason, giving credit for ability and effort, not for gender and<br />

class. The masquerade denies and dismantles the convention.<br />

Further reading:<br />

Holm, Bent, Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>, A Danish Playwright on the European Stage, Hollitzer Verlag,<br />

Vienna 2018, pp. 37–46 (on the condemnation of theatre and masquerades during<br />

the rule of pietism).<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong>, Ludvig, <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume I, Hollitzer Verlag, Vienna 2020, pp. 11–21 (<strong>Holberg</strong>’s<br />

defence of theatre, 1723).<br />

16

EPISTLE 347<br />

from<br />

Epistles <strong>Vol</strong>ume 4<br />

1749<br />

Comprising a number of historical, political, metaphysical, moral,<br />

philosophical and indeed droll matters<br />

17

To * *<br />

In my critical reflections on oaths, 1 it has been shown that a good many oaths<br />

of the greatest implication are attributed the least significance, whereas the most<br />

insignificant are ascribed the greatest weight, so that it is not the oaths in themselves<br />

but the epithets used and the ways in which they are expressed that strike<br />

the various degrees of alarm. The same observations can be made of games and<br />

amusements, given that some of the least morally reprehensible and least improper<br />

are considered most offensive and foolish, in such a manner that outrage seems<br />

greater about the name than about the activity.<br />

No amusement, no pastime is considered more foolish and indecent than that<br />

which carries the name of masquerade, notwithstanding that none of all is more<br />

appropriate and better substantiated; for its very invention is clever, and the<br />

offence consists in its misuse. I say that the invention is clever because it allows<br />

enactment of the original human state, rendering all human beings equal, and it<br />

brings all constraint and onerous rituals to a halt for a while. It is an imitation of<br />

the old Saturnalia, 2 which were held at certain times of year in order to re-evoke<br />

the original human state, when there was no difference between high and low,<br />

between masters and servants, between persons and persons of title and rank. It<br />

is for this reason that folk wear masks during the period of carnival, such that<br />

mixing can be free, without constraint, without fear and deference, such that a<br />

subject might be on terms of familiarity with their King, and a servant with their<br />

master, which cannot be anything other than favourable for high and low alike;<br />

for high, since they can temporarily assume the façon for which many of them<br />

wish but which conventions do not allow them to fulfil, likening them to armed<br />

folk, who feel soothed and able to draw breath once the heavy armour is laid aside,<br />

or to those who walk on stilts so as to seem taller than they are, who feel relieved<br />

at being equal in height to others; it must likewise be favourable for lowly folk<br />

and servants, given that they can accordingly be compared to imprisoned and<br />

confined people for whom the doors to the prison are opened and they are given<br />

freedom to go where they will; because the conventional human state, in which<br />

we live in communities and other social orders, is such that some say with a sigh:<br />

“If only we dared,” others: “If only circumstances would allow us.”<br />

Inasmuch as this was the aim of the masquerades, then it must be admitted<br />

that the invention of such is clever, indeed that it is a philosophical amusement,<br />

or that it at least gives occasion to philosophical reflections, since all thereby are<br />

1 This is a reference to Epistle 267, in which <strong>Holberg</strong> reflects on uses of oaths and the varying effectiveness<br />

of cursing dependent on to whom or to what the oath refers – e.g. God, ill fortune, a dog,<br />

a bitch, a goose.<br />

2 The ancient Roman pagan festival in celebration of the deity Saturn; associated with unrestrained<br />

indulgence, orgiastic revelry.<br />

18

eminded of the condition to which humankind was assigned by God at first creation,<br />

and from which through sin is fallen: it is accordingly possible to say that<br />

the conventional human state in which we live is a constant masquerade, since<br />

social order, conventions and customs impose masks upon us, which in this kind<br />

of amusement we lay aside, as it were, and that strictly speaking we are not truly<br />

masked except when bare faced.<br />

Since this is the origin of the masquerade, it has to be wondered why no other<br />

amusement or pastime is so berated. It is accordingly necessary to look at the other<br />

side of this amusement, and examine the consequences that critics claim arise<br />

therefrom and upon what they base their harsh criticism. They claim that night is<br />

thereby turned into day, and day into night. Such objection has been addressed by<br />

Henrik in the play; 3 and to this I would add that card playing and large evening<br />

meals also turn night into day, and yet these evening and night-time gatherings<br />

are not so besmirched as masquerades, although harsher judgements ought to befall<br />

these given that ailments incurred from the former can be expelled by the latter,<br />

and that folk leave a dance hall more satisfied than they leave a gaming room,<br />

where many lose their wherewithal.<br />

They claim, secondly, that masquerades give occasion for improper love<br />

intrigues. This objection would seem to be of significance in Spain and Italy, where<br />

the lady is locked away and is invisible, but absolutely not here in Scandinavia,<br />

where society between the sexes is open and unconstrained all year round, facilitating,<br />

without the agency of masquerades, declarations of love.<br />

They base, thirdly, their judgement upon the indecency in disguising oneself,<br />

and on men donning women’s costume and women donning men’s costume, taking<br />

corroboration from sermons and writings by the old Church Fathers against this<br />

practice. But a good many reasonable writers, such as M. Barbeyrac, 4 have shown<br />

that the moral philosophy of the old Fathers is often poorly thought through, and<br />

others are of the opinion that many a harsh judgement passed by preachers on<br />

matters of indifference could be scratched from our books of sermons.<br />

My lord must not believe that I am seeking in my letter to recommend<br />

masquerades; for what should compel me to advocate something of which I have<br />

never been a devotee. My intention is purely to show the same error is made here<br />

as is made in the case of oaths; for a blind eye is turned to certain pastimes that<br />

are most misguided and reprehensible. The night-time gatherings held in gaming<br />

houses and wine cellars, where folk sit speaking ill of their neighbour and berating<br />

the authorities until being guided home drunk, are the least vilified, albeit<br />

they give most substance thereto. I will however admit that many have had good<br />

3 A reference to Henrik in Masquerade, Act 2, scene 3, see pp. 50–56.<br />

4 Jean Barbeyrac (1674–1744), a Huguenot refugee from religious persecution in France; a leading<br />

theorist and translator of works on Protestant natural law theory.<br />

19

eason to sermonise against masquerades, since at certain places they have been<br />

the subject of misuse. But the same can be said against all kinds of pastimes when<br />

they are undertaken too often and are hence misused. Everything that occurs of<br />

excess and without moderation becomes reprehensible and damaging; for one can<br />

even eat one’s way to a feverish ailment by means of barley-flour porridge, albeit<br />

this is not only a harmless but also a healthy dish when consumed in an appropriate<br />

quantity.<br />

Otherwise, I can see no good reason for such vehement declamation against<br />

masquerades or denunciation of such amusements; all I can say about the matter<br />

is this: that greater cautiousness must be applied when permitting masquerades<br />

than in the case of other diversions, on account of the great pleasure people derive<br />

herein, and which means that therein no moderation will be kept unless restrictions<br />

are attached. In conclusion, I will say this: that it is hard to understand why<br />

masquerades are considered an innocent amusement and are allowed throughout<br />

Italy and other countries where one might fear ill consequences thereof, whereas<br />

they are denounced in Scandinavia where they can have no ill effects.<br />

I remain, &c.<br />

20

INTRODUCTION<br />

MASQUERADE<br />

(MASKERADE)<br />

Written 1723/24. First performance 1724. Published 1724.<br />

Masquerade presents a patriarchal hierarchical structure in conflict with the masquerade’s<br />

non-hierarchical non-structure. The play delves into the discussion about<br />

the usefulness of the useless, the haven of imagination from the masquerade of convention.<br />

The backdrop to the play – the family – also presents a picture of the (class)<br />

society in which a master of the house sits at the almighty centre while the other<br />

characters, from spouse to servant, (circum)navigate a hierarchical-planetary orbit.<br />

In September 1722, a new playhouse opened in Copenhagen; in addition to<br />

a stage repertoire with plays now for the first time performed in Danish, the<br />

theatre also hosted masquerades. At these masked entertainments, citizens could<br />

leave their ‘normal’ identities at the door and indulge in other varieties of reality<br />

– all the while adding to the theatre’s coffers. This playing with illusion, an<br />

unregulated non-reality with potential for frivolity, caused alarm in the legislative<br />

chambers and after a little over a year the authorities banned masquerades.<br />

<strong>Holberg</strong> wrote his play in defence of the beleaguered theatre, but his efforts were<br />

in vain. The ban was imposed as the play reached the stage – and remained in force<br />

for more than four decades, even after pietism had lost its sway over governance<br />

of the Danish realm. So <strong>Holberg</strong> was defying the formal executive mindset: he<br />

was insisting that the genre was not outrageous, immoral and a waste of time, but<br />

was both useful and necessary; he saw the masquerade as a vitalising recreation<br />

and a thought-provoking corrective to rigid role patterns.<br />

The two fathers in Masquerade – Jeronimus and Leonard – are, respectively,<br />

severely overbearing and moderately tolerant. As men of authority, however, they<br />

have feet of clay. When Jeronimus is challenged by his own wife (Magdelone), and<br />

when Leonard is challenged by his own daughter (Leonora) and her maidservant<br />

(Pernille), cracks appear in the façade and the two men overplay the essence of<br />

their roles: Jeronimus becomes an outright despot, tyrannising his household;<br />

Leonard’s moderation implodes under pressure, and out pops his structural smallmindedness.<br />

Jeronimus has particular difficulty in controlling his son and Henrik<br />

the servant, both of whom have a stronger urge to party than to respect the paternal<br />

rulebook. When matters of the heart disrupt the chain of command, the fathers<br />

find themselves negotiating uncharted terrain.<br />

21

Henrik champions the masquerade with (on the face of it) social arguments.<br />

Leonard stands up for the masquerade on philosophical and moral grounds. Nevertheless,<br />

none of the characters in the play are serving as a spokesperson advocating<br />

the playwright’s opinions. Or rather: in one way or another, they are all doing<br />

just that. Jeronimus sometimes expresses critical opinions with which <strong>Holberg</strong><br />

would agree. Even the servant Arv, albeit something of a killjoy, occasionally<br />

approximates a view shared by his playwright. <strong>Holberg</strong> does not work in any<br />

banal sense with ‘good’ and ‘evil’, ‘wise’ and ‘stupid’ characters; as a bona fide<br />

dramatist, he engages his audience in a dialectic-dialogic arc.<br />

The very concept of the masquerade undermines the patriarchal ideology<br />

imbued with fixed social roles defined on the basis of, for example, gender and class.<br />

Anyone ascribing absolute authority to that roleplay lives in an illusion. Henrik is<br />

a knowing roleplayer; he has no illusions; with his contempt for a stagnated ideology,<br />

he dances along to the anarchic tune of the masquerade.<br />

For a detailed analysis of Masquerade, see:<br />

Holm, Bent, Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>, A Danish Playwright on the European Stage, Hollitzer<br />

Verlag, Vienna 2018, pp. 90–109.<br />

22

MASQUERADE<br />

by<br />

Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong><br />

1723/24<br />

23

Masquerade<br />

Play in 3 Acts<br />

24

Characters:<br />

Jeronimus<br />

Magdelone<br />

Leander<br />

Henrik<br />

Arv<br />

Leonard<br />

Leonora<br />

Pernille<br />

Woman<br />

Man<br />

Two soldiers<br />

Boy<br />

Town watchmen<br />

a townsman<br />

his wife<br />

their son<br />

Leander’s servant<br />

an outdoor servant<br />

a townsman<br />

his daughter<br />

Leonora’s maidservant<br />

delivering masquerade costumes<br />

delivering masquerade masks<br />

25

ACT 1<br />

Scene 1<br />

LEANDER, HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

(in his morning robe, rubbing his eyes) Henrik, what’s the time?<br />

(yawning) Time must be on the way to breakfast, sir, but I<br />

don’t know why we have to get up so early. Just look at the<br />

clock, sir.<br />

Good heavens! Is this possible? Can we really have slept so<br />

long, four hours past dinner? My timepiece says four o’clock.<br />

Ay, that is not possible, sir, it must be four o’clock in the<br />

morning.<br />

You think it’s as light as this at four o’clock in January!<br />

Then the sun can’t be going right. It can’t possibly be<br />

afternoon; we’ve only just got up.<br />

Even if the sun’s not going right, I know my pocket watch<br />

isn’t going wrong; it’s an English watch. 1<br />

Ehh sir, the workings of pocket watches and sundials are<br />

guided by the sun. If you now try to put the sun back to<br />

ten or nine, sir, just you see how the watch will straightway<br />

advance back. No doubt in my mind.<br />

What hogwash. You’re obviously still drunk from the<br />

masquerade.<br />

(yawning) In a word, sir, if it’s only four o’clock, then it’s four<br />

o’clock in the morning.<br />

But we didn’t get home from the masquerade until four<br />

o’clock.<br />

I do actually feel rather hungry. But there’s Arv. I’ll ask him<br />

what time it is.<br />

1 A guarantee of its quality and accuracy. On misleading descriptions in the book trade, <strong>Holberg</strong><br />

later commented (Epistle 126, 1748) that “[…] no shopkeeper hesitates to pass off homemade as<br />

English clothing, and no clockmaker has any scruples about putting London on a pocket watch<br />

made in Copenhagen.”<br />

26

Scene 2<br />

HENRIK, ARV, LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

ARV<br />

HENRIK<br />

ARV<br />

LEANDER<br />

Good morning, Arv. What’s the time?<br />

Had you had as many calamities as there are hours since this<br />

morning, you could be a moneyed man.<br />

So what’s the time now?<br />

The clock is hanging on the steeple, and you ought to be<br />

hanging on the gallows.<br />

Oh hark that ill-bred pillock. Tell me the time, will you?<br />

ARV It’s four o’clock, monsir. 2<br />

LEANDER<br />

ARV<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

ARV<br />

HENRIK<br />

ARV<br />

LEANDER<br />

ARV<br />

LEANDER<br />

ARV<br />

So is it after dinner then?<br />

According to time-honoured reckoning, then it’s past dinner<br />

when it’s four o’clock in the afternoon.<br />

There you have it, Henrik, my pocket watch is working.<br />

The devil take these conventions. Now I’ve slept through my<br />

nice dinner. What did we have for dinner, Arv?<br />

Sweet sago soup, and dried cod.<br />

And you’ve of course left some for me?<br />

No. We gave your share to Sultan the guard dog; because the<br />

master says that anyone who doesn’t come to the table at the<br />

right time may not have any food. You could try getting it<br />

back from Sultan.<br />

Did Papa dine at home?<br />

Yes, he ate in his cage, as he usually does.<br />

Fool! I’m not asking about the parrot, I’m asking about my<br />

father.<br />

No, the master ate with the stranger, Monsieur Leonard,<br />

today.<br />

2 <strong>Holberg</strong>’s characters use several pronunciation versions of ‘monsieur’, a common form of address<br />

for men at the time. They also use ‘Seigneur’ and ‘Mamselle’ as forms of address.<br />

27

LEANDER<br />

(ARV leaves)<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

It’s fortunate, Henrik, that my father didn’t dine at<br />

home, otherwise he would have found out we were at the<br />

masquerade.<br />

Will you not go in and dress, sir; because your father might<br />

arrive at any moment, and it looks a little suspicious to be<br />

wearing a morning robe so late in the day.<br />

If he is with my future father-in-law, then he won’t be<br />

coming so soon.<br />

If I may, sir. Your future sweetheart, is she attractive?<br />

I really have no idea.<br />

It’s odd to marry someone you’ve never seen.<br />

I saw her when she was six years old, at which point she<br />

looked like she would turn out very pretty.<br />

So how old is she now?<br />

Eighteen.<br />

Good heavens, the lustre could have worn off in all that time.<br />

But people say she’s still pretty. I’m going over there<br />

tomorrow, so I’ll see if it’s true. If she is not as she has been<br />

described to me, then the visit will end at the civilities. But<br />

let’s go in and see if we can get some food; time is flying<br />

by. We’ll be off to the masquerade again at eight.<br />

Ay, excellent. I expect lots of fillies there this evening.<br />

It is to be regretted, Henrik, that so many common girls show up.<br />

Eh, sir, that’s the blessing of the masquerade, everyone’s<br />

treated alike as peas in a pod. Besides, all the mamselles I’ll<br />

be seeing are quality folk, I can assure you. There’s one of<br />

the mayor’s housemaids, Per the saddler’s daughter, Else the<br />

schoolmaster’s daughter, Lisbed the bitter-orange-seller’s<br />

youngest daughter (because her eldest has the toothache),<br />

along with three other lovely unattached girls who live off<br />

their assets. 3<br />

3 The ‘toothache’ is most likely a euphemism for pregnancy; ‘live off their assets’ is most likely a<br />

euphemism for prostitution.<br />

28

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

LEANDER<br />

HENRIK<br />

No truer word, Henrik, all quality folk, particularly the<br />

three who live off their assets.<br />

But here comes the lady of the house.<br />

My mother is welcome. Perhaps I can persuade her to come<br />

along to the masquerade this evening.<br />

Well that would be fun. I shall, upon my word, dance with<br />

her.<br />

If she doesn’t recognise you, then that might very well be the<br />

case.<br />

Consider it done. I’ll make sure I’m masked in such a way<br />

that she won’t recognise me.<br />

29

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

LEANDER<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

(She sings and dances)<br />

HENRIK<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

HENRIK<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

Scene 3<br />

MAGDELONE, LEANDER, HENRIK<br />

My dear son, how was the masquerade last night?<br />

How does Mama know that I was there?<br />

I heard it from Arv.<br />

That lad can never keep his mouth shut. But it doesn’t matter,<br />

so long as my father doesn’t get to hear about it.<br />

Do old ladies attend the masquerade, too?<br />

We don’t refuse anyone entry, young and old alike attend.<br />

If an old lady is not refused entry, then I know someone who<br />

would like to attend this evening.<br />

Which lady would that be?<br />

That would be me myself.<br />

Why, faith, not a bad idea, on condition that it is done in so<br />

artful a fashion that my father doesn’t get to hear of it.<br />

Ay, how would he get to hear of it? He is early to bed and late<br />

to rise. I shall say that I am unwell this evening, then he’ll<br />

sleep on his own.<br />

That could work, but can Mama dance?<br />

Dance? Yes, upon my word I can, look at this.<br />

Good heavens! My lady’s feet are going like drumsticks.<br />

In my youth, I could dance every dance in the book up to and<br />

including the Folie d’Espagne. See, it goes like this. (dances<br />

and sings a Folie d’Espagne) 4<br />

That went admirably, I must say. Ah, give us another<br />

folie, good lady.<br />

No, I shall save my legs for this evening. But there is my husband.<br />

I hope he didn’t see me dancing.<br />

4 French version of the originally Iberian La Folia, an old European musical theme – here accompanying<br />

a dance.<br />

30

Scene 4<br />

JERONIMUS, MAGDELONE, HENRIK, LEANDER<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

HENRIK<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

(has a little beard) 5 Are you all just standing here, my dears,<br />

so idle? Is there nothing to occupy you in the house?<br />

I am incapable of doing anything today, dear heart. For, faith,<br />

I have as if a fever in my body, so I fear I shall have a restless<br />

night tonight.<br />

That pains me to hear. Is it in your head?<br />

Ah yes. It feels as if my head were cloven.<br />

Are you also thirsty?<br />

Intolerably. And I have such restlessness in my body, too, that<br />

I must sleep alone this night.<br />

Indeed, you are more than welcome. But since you have a<br />

bout of fever, you must act before it is too late. You must be<br />

bled.<br />

Ah no, dear heart, to be sure, I am not so very ill that I must<br />

resort to bleeding.<br />

What nonsense. Do you really want to be bedridden with a<br />

fever tomorrow? Henrik, run and fetch Master Herman, 6 and<br />

request him to come hither and bleed my wife.<br />

(aside) Good heavens! How is this going to turn out?<br />

Ah no, my dear husband!<br />

Hush, dear heart, I shall be the judge of that. Let me feel<br />

your pulse. Good heavens, it is high time you were bled. I<br />

detect an imbalance in your veins. 7 Off you go immediately,<br />

5 Beards had fallen out of fashion at the time the play was written, so Jeronimus is being characterised<br />

as an old-fashioned gent, and in Act 3, scene 7 it is this beard that leads to him being thought<br />

Jewish.<br />

6 Master Herman, the barber, appears in several of <strong>Holberg</strong>’s plays; at the time, barbers also undertook<br />

procedures that were later the domain of medical doctors (bleeding, treating sores and<br />

fractures, for example).<br />

7 Reference to the Ancient Greek theory of the ‘humours’, still current in the early 18th century,<br />

whereby the body was a system of four fluid ‘humours’ or ‘temperaments’: blood, phlegm, black<br />

bile and yellow bile. Any imbalance of these vital fluids could cause physical illnesses or personality<br />

disturbances.<br />

31

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

LEANDER<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

LEANDER<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

LEANDER<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

HENRIK<br />

Henrik, and request him to attend personally; for I do not<br />

trust any of his assistants in this matter.<br />

Ah, my very dearest husband, just allow me to wait and see<br />

for an hour or so first.<br />

An hour or so will make no difference. But you will, upon<br />

my word, be bled before you go to bed. And you, young<br />

buck, why are you still in your morning robe at this advanced<br />

hour. You were perhaps, as usual, out late last night?<br />

No, in faith, I was not. I have been busy writing all day long.<br />

I would wish that were the case, and that the time will come<br />

when you might adopt a sober-minded life style. You are<br />

already of an age when you ought to start thinking more<br />

sensibly and abandon the coxcombry for which you have a<br />

penchant.<br />

But I have never committed any excesses other than those<br />

committed by most young people in this town.<br />

Meaning: you have sometimes partaken of lavish banquets,<br />

gambled away your money, chased women and lived like a<br />

veritable Jean de France. 8 There is nothing odious in this; for<br />

most young people live in a similar fashion.<br />

So did you, Papa, live a restrained life in your youth?<br />

In my youth, people lived in an entirely different fashion,<br />

albeit we had twice as much money. There were only four<br />

closed carriages in the whole town. Distinguished persons<br />

were seen being guided home by their maidservants carrying<br />

lanterns. Were the weather bad, you wore boots. In my<br />

youth, I had no idea what it was like to ride in a carriage.<br />

Now, however, you cannot walk three paces without having a<br />

servant idling at your heels, or pass along a street without the<br />

services of a conveyance.<br />

Then the streets can’t have been so mucky as they are now.<br />

8 Title character from <strong>Holberg</strong>’s play Jean de France, first performance 1722, in which ‘Jean’ (real<br />

name: Hans Frandsen) is ridiculed for his fixation with all things French. He also features in<br />

Witchcraft, or False Alarm (see Ludvig <strong>Holberg</strong>: <strong>Plays</strong>, <strong>Vol</strong>ume II).<br />

32

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

HENRIK<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

That is true, the streets were clean. But what causes their<br />

uncleanness other than all those coaches? In the old days,<br />

fine folk walked to Gyldenlund, 9 but it is now considered<br />

ignominious to walk beyond the town gates. Is what I say not<br />

true, my dear wife?<br />

Certainly. I lived in my parents’ house as if living in a<br />

convent.<br />

You poor lady.<br />

Thus, I now have no desire for worldly foolishness; for I<br />

acquired no taste for it in my youth.<br />

9 Gyldenlund: now Charlottenlund Forest and Castle, just north of Copenhagen. The area had been<br />

taken over by King Christian IV in 1622 and laid out as a deer park. In 1663, King Frederik <strong>III</strong> had<br />

given permission for the area to include an inn and entertainment (and a brothel). Around 1672,<br />

one of the king’s illegitimate children, Ulrik Frederik Gyldenløve, took over the area, which then<br />

became known as Gyldenlund (‘golden grove’). In 1682, the area returned to the Crown and in<br />

1690 Christian V built a small castle, rebuilt in 1733 and renamed Charlottenlund Slot (Castle).<br />

33

Scene 5<br />

A WOMAN (carrying masquerade costumes), JERONIMUS, MAGDELONE, HENRIK<br />

WOMAN<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

WOMAN<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

WOMAN<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

HENRIK<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

WOMAN<br />

HENRIK<br />

WOMAN<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

My dear lady, here is the masquerade costume you ordered.<br />

I’m quite sure it will fit you.<br />

What the devil is this? Are you going to the masquerade?<br />

She must have come to the wrong place, my dear husband.<br />

To whom shall the masquerade costume be delivered,<br />

clothier?<br />

To the lady who has ordered it for this evening.<br />

You have been hoodwinked, my child. It is not for my wife.<br />

That’s strange, she sent for me half an hour ago.<br />

Shame on you, lying about me like that.<br />

She’s drunk, sir, plumes of snaps 10 are rising from her throat<br />

like smoke from a chimney.<br />

Go home and sleep it off, goodwife.<br />

How hideous a spectacle is a drunken woman.<br />

(weeping) No one is telling the truth when accusing me of<br />

drinking. I might be poor, but I am nonetheless honest.<br />

(aside) If she wasn’t bled before, then she surely will be now.<br />

She stood there just half an hour ago and spoke with me and<br />

said she was going to the masquerade and asked me to provide<br />

her with a lovely costume. Yes, really, that she did. I am<br />

neither drunk nor crazy.<br />

Get away from me, woman, I can’t stand that stench of snaps.<br />

If you do not leave, I shall have you marched off to spin yarn<br />

in the house of correction.<br />

10 A Danish form of aquavit with a high alcohol content.<br />

34

A MAN<br />

WOMAN<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

Scene 6<br />

A MAN, WOMAN, JERONIMUS, MAGDELONE<br />

(enters carrying a selection of masks) Here are some masks, my<br />

lady, now you can choose the one that fits best, but they cost<br />

two rix-dollars 11 apiece.<br />

Can you see now, sir, that I’m neither drunk nor crazy?<br />

Aaah! This is disgraceful. Now I understand where that fever<br />

comes from, that restlessness in your body, why you want to<br />

sleep on your own.<br />

MAGDELONE But my dear husband ...<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

MAGDELONE<br />

JERONIMUS<br />

(They leave)<br />

Hush, you cannot dress this up to look any better than it is.<br />

A woman of your age going to a masquerade! What a fine<br />

example to set young people, particularly your child and the<br />

servants.<br />

I just the once wanted to see what goes on there, so I would<br />

then be better equipped to reprimand others.<br />

A splendid excuse! Just you stay indoors with no further ado,<br />

madam, and keep out of everyone’s sight for a few days until<br />

you have done penance. And you others, with your masks and<br />

masquerade costumes, if you ever come to my house again<br />

with such fripperies, I shall see to it that you have your arms<br />

and legs broken.<br />

11 Former northern European silver coin and money of account used for domestic and trading purposes.<br />

One Danish rigsdaler was of not inconsiderable value.<br />

35