You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

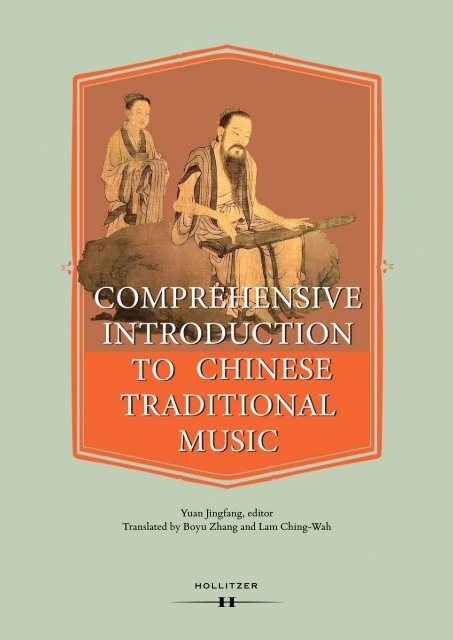

Yuan Jingfang, editor<br />

Translated by Boyu Zhang and Lam Ching-Wah

Comprehensive Introduction to <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

<strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong>

National Key Teaching Materials for<br />

General Higher Education<br />

<strong>Chinese</strong> Arts Education Series · <strong>Music</strong> Volume<br />

Comprehensive Introduction to <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

<strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong><br />

Yuan Jingfang (Editor-in-Chief)<br />

Zhou Qingqing, Yang Minkang,<br />

Zhang Hongyi, and Qian Rong<br />

Translated by Boyu Zhang and<br />

Lam Ching-Wah<br />

Central Conservatory of <strong>Music</strong> Press

Yuan Jingfang (ed.):<br />

Comprehensive Introduction to <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong><br />

Translated by Boyu Zhang and Lam Ching-Wah<br />

Wien: HOLLITZER Verlag, 2023<br />

Cover Image<br />

Wang Zhenpeng: Boya Playing Qin (detail), Yuan dynasty (1271-1368),<br />

The Palace Museum, Beijing<br />

All rights reserved<br />

© Central Conservatory of <strong>Music</strong> Press, Beijing and Hollitzer Verlag, Wien<br />

Printed and bound in the EU<br />

ISBN 978-3-99094-097-6 (e-book)

NOTES FROM THE TRANSLATORS<br />

This book is translated from the <strong>Chinese</strong> book entitled Introduction to <strong>Traditional</strong><br />

<strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong>, one of the books of <strong>Chinese</strong> Art Education Series, published by<br />

the Shanghai <strong>Music</strong> Press in 2000. The <strong>Chinese</strong> version is part of “National Key<br />

Teaching Materials” of “Ninth Five-Year Projects” (1996–2000) for General Higher<br />

Education—<strong>Chinese</strong> Arts Education Series·<strong>Music</strong> Volume. The authors include the<br />

teachers from the <strong>Music</strong>ology Department of Central Conservatory of <strong>Music</strong>, Yuan<br />

Jingfang, Zhou Qingqing, Yang Minkang, Zhang Hongyi, Qian Rong. The chief<br />

editor is Prof. Yuan Jingfang. General Editorial Board of <strong>Chinese</strong> Arts Education<br />

Series include: General Editor-in-Chief Zhao Feng; Honorary Director Pan Zhenzhou;<br />

Director: Tao Chunxiao; Deputy Directors Du Changsheng, Lin Yongjun, Dai Jiafang,<br />

Wang Jinsui; Executive Director Ying Feng; Executive Deputy Directors Zheng<br />

Shuzhen, Zhu Qi, Niu Gengfu; together with 31 board members.<br />

Members of the Editorial Board of Introduction to <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong><br />

include Editor-in-chief: Yuan Jingfang; Deputy Editor-in-chief: Zhou Qingqing;<br />

Editorial Board: (in order of strokes of <strong>Chinese</strong> Characters): Xiao Xuejun, Yang<br />

Minkang, Zhang Hongyi, Zhou Qingqing, Xiang Yang, Qian Rong, Yuan Jingfang.<br />

During the translation, several changes have been made by the translators. The<br />

first, the <strong>Chinese</strong> version of the book includes two parts: <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong><br />

and <strong>Chinese</strong> Religious <strong>Music</strong>. The English version contains only the first part.<br />

The second, during the translation, the translators follow the text flow of the<br />

<strong>Chinese</strong> version, but added explanation sentences and made slightly necessary<br />

variations in order to be understandable by English readers.<br />

The third, the <strong>Chinese</strong> terms appeared with the Pinyin romanizations and English<br />

translations, either the <strong>Chinese</strong> Pinyin first, with the English translation in brackets, or<br />

English translation first, with the Pinyin in brackets, depending on the text flow.<br />

The fourth, Pinyin romanizations of names of books as well as their English<br />

translations in brackets are italic; other terms, such as instrument names, song titles,<br />

etc., only Pinyin romanizations using italic, if the <strong>Chinese</strong> Pinyin is first, and both<br />

italic, if the English translation is first.<br />

The fifth, a long list of <strong>Chinese</strong> glossary is added at the end of the book.<br />

The sixth, a bibliography and recommended sound recordings that were listed at<br />

end of each chapter in <strong>Chinese</strong> have been moved to the end of the book.<br />

The seventh, as a theoretical book, it is impossible to show too many music<br />

examples necessary to discuss music artistic features. Readers can find most of the<br />

music pieces discussed in the book in the <strong>Music</strong> Scores Compiled for the Course of the<br />

“Introduction to <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong>” (2 volumes), edited by Zhou Qingqing,<br />

and published by the Central Conservatory of <strong>Music</strong> Press in 2007.<br />

Beijing, 2022

LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES<br />

Note: The mark indicates that audio examples are available at the Central<br />

Conservatory of <strong>Music</strong> Press.<br />

Chapter I<br />

Example 1-1. Bend Your Back to Hook the Timber (Hayao’gua)<br />

Example 1-2. Tamping Song (Dawo’ge) from Macheng, Hubei Province<br />

Example 1-3. Rice-husking Song (Chongmi Haozi)<br />

Example 1-4. Introduction and Sanyao’tai part of Lishui River Boatmen Song (Lishui<br />

Chuangong Haozi)<br />

Example 1-5. Jiaofu Diao (Tune of the Deliverer)<br />

Example 1-6. The Mountain Keeps Us Apart (Liaobujian Meimei Shan Dangzhule)<br />

from Hequ, Shanxi<br />

Example 1-7. Typical use of Zhi mode of mountain songs of Jiangsu and Zhejiang<br />

Example 1-8. Picking Grapes. Eastern Sichuan mountain song, arranged by Zheng<br />

Chenglu<br />

Example 1-9. All the Way Following the Sun. Sichuan Shange (Mountain Song of<br />

Sichuan)<br />

Example 1-10. Ganma’diao (Horse Riding Song), from Binchuan, Yunnan<br />

Example 1-11. Midu Shange (Midu Mountain Song), from Midu, Yunnan<br />

Example 1-12. Shuiniuer (Water Snail), from Beijing<br />

Example 1-13. Embroidering a Small Pouch (Xiu’hebao), from Cangshan, Shandong<br />

Example 1-14. Embroidering a Small Pouch (Xiu’hebao), from Yibin, Sichuan<br />

Example 1-15. Peng’hama (Weighing Crabs), from Qianjiang, Hubei<br />

Example 1-16. Mengjiang’nu (Lady Mengjiang), from Jiangsu<br />

Example 1-17. Farewell My Love (Song’qinglang), from Liaoning<br />

Example 1-18. Dropping Watermelon (Shuai’xigua), from Shenxian, Hebei<br />

Example 1-19. Flower Drum Tune (Huagu Diao), from Kaifeng, Henan<br />

Example 1-20. Visiting In-Law’s Family (Tan’qingjia), from Central Hebei<br />

Example 1-21. Meeting Mother-in-Law (Hui Qingjia), from Linxi, Hebei<br />

Example 1-22. The tone row used in the song Laili Gul<br />

Example 1-23. Arirang, from Luda, Liaoning<br />

Example 1-24. The third phrase of Gesangla<br />

Example 1-25. The fourth phrase of Gesangla

VIII<br />

LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES<br />

Chapter II<br />

Example 2-1. Caicha’yao (Tea-picking Ballad) of Yudu, Jiangxi<br />

Example 2-2. Tea-picking in Twelve Months from Yulin, Guangxi<br />

Example 2-3. Kaihuang (Cultivation from Bare Land) in Yulin Tea-picking Genre<br />

Example 2-4. Song of Wang Sanjie Ganji (Sister Wang Goes to Market)<br />

Example 2-5. The dance song Shidui Hua (Ten Passages of Flower Song)<br />

Example 2-6. Badou Kaihua (Croton is Blossoming, also called “Laoninglang”).<br />

Female chorus, Cangyuan County, Yunnan<br />

Example 2-7. Melodic variation of Liu Qingniang (Slender Lady)<br />

Example 2-8. The main section of the dance music for Lusheng<br />

Example 2-9. Melody development of the dance music for Lusheng<br />

Example 2-10. Jiaoban Dian (Starting Rhythmic Pattern) of Shandong Guzi Yangge<br />

(Drum Field Dance of Shandong)<br />

Example 2-11. Proceeding drumbeat of Shandong Guzi Yangge (Drum Field Dance of<br />

Shandong)<br />

Example 2-12. Ending rhythmic pattern of Shandong Guzi Yangge (Drum Field Dance<br />

of Shandong)<br />

Example 2-13. Rhythmic patterns of percussion music of Elephant-Foot Drum Suite<br />

of Peacock Dance in Dehong Prefecture<br />

Example 2-14. Gengu’diao (Hanban’guang), sung by Jing E<br />

Example 2-15. The structure of single-section piece in Sänäm of Naghma of Čäbbiyat<br />

Muqam<br />

Example 2-16. The most common scales used in the Twelve Muqam<br />

Example 2-17. The Rhythms of Dap Hand Drum<br />

Chapter III<br />

Example 3-1. Wukongzai “Antong’nao”<br />

Example 3-2. Sikongzai “Ma Sange” (Scolding Third Brother)<br />

Example 3-3. “Haidi’fan” (Rebellion under the Sea), a piece belongs to Wukong<br />

Zanianzai (Varied Recitals in the Wukong Mode)<br />

Example 3-4. Fengyangge (Fengyang Song) “Shuangganche” (On the Cart)<br />

Example 3-5. Duozi’ban used in Liangzhu Xiashan (Liang and Zhu Departing the<br />

Mountain)<br />

Example 3-6. A comparison of two versions of Xianhua’diao (Flower Tune)<br />

Example 3-7. Early version of Changcheng’diao (Excerpt from Duanqiao)<br />

Example 3-8. Changcheng’diao (Tune of the Great Wall) (Excerpt from Duanqiao,<br />

Broken Bridge).<br />

Example 3-9. Chaqu song Wanxia (The Sunset Glow) sung by Ma Tanhui<br />

Example 3-10. Yaeryo from Danxian Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-11. Daxin’chun (The New Year Begins) (Excerpt from Dangpi’xiang-<br />

Pawning the Leather Trunk)<br />

Example 3-12. Qutou (Opening Tune) used in Danxian Paiziqu

LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES<br />

IX<br />

Example 3-13. Shuchang (Rapping Tune) used in Danxian Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-14. Taiping’nian (Peaceful Year) used in Danxian Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-15. Nancheng Diao (Southern City Tune) used in Danxian Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-16. Qie’kuaishu (Rural Copper Clapper Reciting) used in Danxian<br />

Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-17. Liushui’ban (Flowing Water Beat) used in Danxian Paiziqu<br />

Example 3-18. Hongna’ao (Red Padded Jacket) used in Sichuan Jinqianban<br />

Example 3-19. Sichuan Jinqian’ban: Xiucai Guogou (A Scholar Crossing the Ditch)<br />

Example 3-20. Linchong Fapei (Banishment of Lin Chong) from Jingyun Dagu<br />

Example 3-21. First phrase of Zhaoyun Jiejiang (Zhao Yun Recovering Liu Shan in<br />

the River)<br />

Example 3-22.The Long Melody in Linchong Fapei (Banishment of Lin Chong)<br />

Example 3-23. Linchong Taxue (Lin Chong Walking in the Snow). Chen Style, sung<br />

by Liu Tianyun<br />

Example 3-24. Gongyuan (Complaints from the Palace). Yu Style, sung by Zhu<br />

Huizhen<br />

Example 3-25. Yingying Baiyue (Cui Yingying Worshipping the Moon). Xiao<br />

Yangdiao, sung by Yang Renlin<br />

Example 3-26. Sidiao from Shuang Zhufeng (Huo Dingjin Mourning for Her<br />

Husband). Qi Style, sung by Qi Lianfang<br />

Example 3-27. Fangqing Xie’jiaxin (Fang Qing Writing a Family Letter). Ma Style,<br />

sung by Wei Hanying.<br />

Example 3-28. Kuta of Zhenzhu Ta (Crying before the Pagoda in The Pearl Pagoda),<br />

Suzhou Tanci<br />

Example 3-29. Youhui Jidi (Swimming Back to the Base) in Jiang Style, Suzhou<br />

Tanci<br />

Example 3-30. Du Shiniang (Lady Du Shiniang), Suzhou Tanci<br />

Example 3-31. Danyu Fengao (Daiyu Burning Manuscripts), Suzhou Tanci<br />

Chapter IV<br />

Example 4-1. Chao’tianzi (Paying Respect to the Emperor), version 1. Unison chorus<br />

in Act Hunting of the Play Huanshaji<br />

Example 4-2. Chao’tianzi (Paying Respect to the Emperor) , version 2. Unison chorus<br />

in Act Hunting of the Play Huanshaji<br />

Example 4-3. Shanpo’yang (The Sheep on Hill), version 1. Vocal melody sung by<br />

Wu Feixia (female role) in Act Cangzhou (Hiding the Boat) of the Play<br />

Yujia’le (Happiness of A Fishing Family)<br />

Example 4-4. Shanpo’yang (The Sheep on Hill), version 2. Song sung by Du Liniang<br />

(female role) in Act Jingmeng (Waking Dream) of the Play Mudan’ting<br />

(Love Story of the Peony Pavilion)<br />

Example 4-5. Possible melodic flow for the <strong>Chinese</strong> character “Yin” in level tone used<br />

in Kunqu opera

X<br />

LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES<br />

Example 4-6. Possible melodic flow for the <strong>Chinese</strong> character “Yang” in rising tone<br />

used in Kunqu opera<br />

Example 4-7. The relationship between melody and text in Mandarin and Suzhou<br />

dialects<br />

Example 4-8. Lanhua’mei (Skipping Make Up for Eyebrows), a Labelled Piece of<br />

Chuanju Gaoqiang<br />

Example 4-9. The padding character using the rhyme of the preceding character<br />

Example 4-10. Dragging tunes must use the “an” rhyme<br />

Example 4-11. The application of padding words displaying the most distinctive<br />

geographical characteristics<br />

Example 4-12. Colorful tune used in Qinqiang Opera<br />

Example 4-13. Song of Cui Jinding in Sanshang’jiao (The Chaste Female Who Takes<br />

Revenge) sung by Chen Suzhen<br />

Example 4-14. Song of Bai Suzhen in Baishe’zhuan (Legend of the White Snake)<br />

sung by Chang Xiangyu<br />

Example 4-15. A long first of the Paired Phrases of Erhuang Original Best in Beijing<br />

Opera<br />

Example 4-16. The Condensed Paired Phrases of Erhuang Original Best in Beijing<br />

Opera<br />

Example 4-17. A long second of the Paired Phrases of Erhuang Original Best in<br />

Beijing Opera<br />

Example 4-18. “Ending Phrases” of Erhuang Original Best in Beijing Opera<br />

Exmaple 4-19. Comparison of the melodic, metric and modal structures between<br />

Original Metre used by male and female roles<br />

Example 4-20. The character “er” is clearly pronounced in Pingju Opera<br />

Example 4-21. Gadayin of Pingju<br />

Example 4-22. Madam Xianglin (Xianglin’sao)<br />

Example 4-23. Fanyue’diao Tune Pattern used in Pingju Opera<br />

Example 4-24. Two paired phrases of five-character phrase used in Pingju Opera<br />

Example 4-25. Nanqiang’diao (Southern Melodies) used Yuejuin Opera<br />

Example 4-26. Sigong’qiang used in Yueju Opera<br />

Chapter V<br />

Example 5-1. Comparison of the melodies of the first four phrases in four variations<br />

of Wu’bangzi to appreciate the performing style of Feng Zicun and folk<br />

wind music in general<br />

Example 5-2. The introduction of Qudi flute piece Zhegu’fei (Flying Partridges,<br />

arranged by Lu Chunling)<br />

Example 5-3. Prelude of South Liaoning Wind-and-Drum Piece Jianghe’shui (Water<br />

in River)<br />

Example 5-4. Bainiao Chaofeng (Hundred Birds Facing the Phoenix), from First<br />

Section

LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES<br />

XI<br />

Example 5-5. The Introduction and Theme of Erquan Yinyue played by Abing in<br />

1950. Transcribed by Yang Yinliu, with fingering by Chu Shizhu and Li<br />

Songshou<br />

Example 5-6. Excerpt from Erquan Yingyue<br />

Example 5-7. Prelude of Tingsong. Performed by Hua Yanjun, 1950<br />

Example 5-8. Theme A of Erhu Piece Guangming’xing<br />

Example 5-9. Theme B of Erhu Piece Guangming’xing<br />

Example 5-10. Excerpt from second section of Qin Piece Meihua Sannong<br />

Example 5-11. Excerpt from the second section of Liushui<br />

Example 5-12. Excerpt from the fourth section of Liushui<br />

Example 5-13. Comparison of melodies of each section of Chaozhou Zheng piece<br />

Hanya Xishui: Erban, Kaopai, Sanban, Sanban Cui<br />

Example 5-14. Excerpt from Yuzhou Changwan<br />

Example 5-15. Excerpt from Lieying of Shimian Maifu<br />

Example 5-16. “Wujiang Ziwen” from Shimian Maifu<br />

Example 5-17. Excerpt from Yinggu of Pipa piece Bawang Xiejia<br />

Example 5-18. Excerpt from Shengzhang of Pipa piece Bawang Xiejia<br />

Example 5-19. Bieji of Pipa piece Bawang Xiejia<br />

Example 5-20. The prelude and the theme of Xiyang Xiaogu (Sounds of Vertical Flute<br />

and Drum at Moonlit Night)<br />

Example 5-21. Theme of Jiangnan Sizhu piece Sanliu (Three-six)<br />

Example 5-22. “Yunyang Ban” of Jiangnan Sizhu piece Xingjie<br />

Example 5-23. Excerpt from Cantonese music Yuda Bajiao<br />

Example 5-24. Excerpt from first section of Cantonese music Shuangsheng’hen<br />

Example 5-25. Excerpt from Sailong Duojin<br />

Example 5-26. Prelude and theme of Chaozhou Xianshi music Shizi Xiqiu<br />

Example 5-27. “Hewei” (Common Tail) of each section of Fujian Nanyin piece<br />

Bajun’ma<br />

Example 5-28. First section of Fanglyu of “Association of Southern Style”<br />

Example 5-29. Excerpt from the third section of Fanglyu<br />

Example 5-30. Excerpt from the piece “Caicha” of Badatao in north Shanxi province<br />

Example 5-31. “Sanban” of Luxinan Guchui’yue Yizhi Hua (A Flower) performed by<br />

Ren Tongxiang, with score transcribed by Chen Jiaqi<br />

Example 5-32. Excerpt from “Suizi” of Luxinan Guchui’yue: Dahe’tao<br />

Example 5-33. Luogu Paizi piece Shiba Liusi’er<br />

Example 5-34. Luogu Paizi piece Yuhe’ba<br />

Example 5-35. “Hetou”(Common Head) of “Dasi’duan”<br />

Example 5-36. Ending of first part of Hou Manting’fang<br />

Example 5-37. Excerpt from Jiangjun Desheng’ling<br />

Example 5-38. First “Xia” of Xi’an Guyue “Full Set of Eight-Beat Sitting <strong>Music</strong> in<br />

Chediao Mode and Using Double Yunluo Set of Gongs”: Chi-Gong-<br />

Chi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

Illustration 1-1. The structure of A Man is Singing a Mountain Song Outdoors<br />

Illustration 2-1. The structure of Yulin (Guangxi) Tea-picking Songs and Dances<br />

Illustration 2-2. The structure of Gengu’diao<br />

Illustration 2-3. Second Mashrap of the Rak Muqam and its binary structure<br />

Illustration 2-4. The structure of the melody in Sänäm of Naghma of Čäbbiyat Muqam<br />

Illustration 3-1. Phrasal relationship of Chaqu between melody and lyrics<br />

Illustration 3-2. Thirteen Rhymes of <strong>Chinese</strong> Putonghua<br />

Illustration 3-3. Part of the verses of Ezuo Mizuo (Sky and Earth) from Hani ethnic<br />

group<br />

Illustration 4-1. Outlines of the characteristics of Banqiang form<br />

Illustration 4-2. Outlines of the characteristics of Qupai form<br />

Illustration 4-3. The “Four-tone Melodic Pattern” of South Kunqu<br />

Illustration 4-4. Relationship of Bang (Vocal ensemble accompaniment), Da<br />

(percussion) and Chang (singing) in Sichuan Opera<br />

Illustration 4-5. Chuanju uses unique symbols, pronunciations and beating methods of<br />

its notation forpercussion music<br />

Illustration 4-6. A list of Xiqu Genres based on Bangzi Melodic Type<br />

Illustration 4-7. Characteristics of Banhu fiddle in different operatic genres<br />

Illustration 4-8. Classification and explanations of the metircal patterns of Qinqiang<br />

Illustration 4-9. Yudong melodic style<br />

Illustration 4-10. Metrical patterns of Yuju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-11. Schools and transmission relationship of Beijing Opera<br />

Illustration 4-12. The classification of roles of Beijing Opera<br />

Illustration 4-13. Metrical patterns of Erhuang<br />

Illustration 4-14. Metrical patterns of Xipi<br />

Illustration 4-15. Rhythmic patterns of Zhengdiao in Pingju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-16. Rhythmic patterns of Fandiao in Pingju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-17. The voice ranges of Yuediao of Pingju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-18. Metrical patterns used in Pingju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-19. Metrical patterns used in Zhengdiao Pile Metre (Duoban) of Pingju<br />

Opera<br />

Illustration 4-20. Metrical patterns of Manban and Mizi of Pingju Opera<br />

Illustration 4-21. Metrical patterns of Pingju<br />

Illustration 4-22. 28 Initials notated in Yue dialect<br />

Illustration 4-23. 41 Vowels, including “r,” but not appeared in the table, notated in<br />

Yue dialect

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

XIII<br />

Illustration 4-24. The relationship between the <strong>Chinese</strong> characters with entering tone<br />

and melody treatments<br />

Illustration 5-1. The tuning and range of each type of Banhu<br />

Illustration 5-2. The range of Zheng of different designs<br />

Illustration 5-3. There are different ways of tuning the Pipa, three most common ones<br />

being<br />

Illustration 5-4. The modes of each piece of “Thirteen Suites for String Ensemble”<br />

and the relationship of key and tuning system for each instrument<br />

Illustration 5-5. Illustration of the names of the modes, fingerings and the relationship<br />

between keys and tunings of strings of Erren’tai Paizi’qu<br />

Illustration 5-6. The relationship of mode names, fingerings, tunings, pitch names and<br />

pitches of leading instruments Dizi and Erhu in Jiangnan Sizhu music<br />

Illustration 5-7. The names of the modes, the relationship between keys and tunings of<br />

strings of Yuehu fiddle used in Guangdong Yinyue<br />

Illustration 5-8. The relationship of keys, fingering sequences and pitches of Guanzi<br />

Pipe as principal instrument in ensemble of “Association of Southern<br />

Style”<br />

Illustration 5-9. The relationship of mode names, fingering techniques and tone pitch<br />

of Guanzi pipe as principal instrument of Badatao<br />

Illustration 5-10. Key relationships of the four modes used in Badatao of Shanxi<br />

Illustration 5-11. The relationship of modal names, fingering sequences and keys of<br />

Suona in the Luxinan Guchui’yue<br />

Illustration 5-12. The relationship of modes, fingering techniques and pitches of the<br />

Suona used in Wind-and-Drum <strong>Music</strong> in Shanxi Province<br />

Illustration 5-13. The relationship of modes, fingering techniques and pitches of<br />

Suona used in Wind-and-Drum <strong>Music</strong> in Liaoning<br />

Illustration 5-14. The relationship between modal names, fingering techniques,<br />

degrees and pitches of Di flute used in Shifan Luogu<br />

Illustration 5-15. Characteristics of rhythmic changes of each variation of “Dasi’duan”<br />

(Great Four Variations) of Xiaxi’feng of Shifan Luogu<br />

Illustration 5-16. Arrangement of Ten Sets Gongs in Zhedong Luogu<br />

Illustration 5-17. Key names, fingerings, tablature pitches and key relations of the<br />

Suona<br />

Illustration 6-18. The plan of sitting music shawm in Zhedong Luogu<br />

Illustration 5-19. Pitches (in Gongche notation) of the double Yunluo

Contents<br />

Notes from the translator and proofreader<br />

List of music examples<br />

List of illustrations<br />

V<br />

VII<br />

XII<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

I. Long History of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 1<br />

II. Rich Connotation of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 8<br />

III. Main Features of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 11<br />

CHAPTER I FOLK SONGS<br />

● SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 17<br />

I. Definition of Folk Songs 17<br />

II. Historical Evolution of Folk Songs 17<br />

III. Status of Folk Songs in Lives of the <strong>Chinese</strong> 18<br />

● SECTION 2 TYPES OF FOLK SONGS AND THEIR<br />

ARTISTIC FEATURES 29<br />

I. Folk Songs of Han People 29<br />

II. Genres of Folk Songs of Ethnic Groups 69<br />

CHAPTER II DANCE MUSIC<br />

● SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 85<br />

I. Definition of Dance <strong>Music</strong> 85

XVI<br />

Contents<br />

II. Historical Evolution of <strong>Chinese</strong> Dance <strong>Music</strong> 85<br />

III. Artistic Features of Folk Dance 94<br />

● SECTION 2 DANCE MUSIC AND ITS ARTISTIC FEATURES 98<br />

I. Vocal Dance <strong>Music</strong> 98<br />

II. Instrumental Dance <strong>Music</strong> 121<br />

III. Composite Dance <strong>Music</strong> 137<br />

CHAPTER III NARRATIVE SINGING<br />

● SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 151<br />

I. Definition of Narrative Singing 151<br />

II. Historical Evolution of Narrative Singing 153<br />

III. The Position of Narrative Singing in <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> Culture 165<br />

● SECTION 2 CATEGORIES AND ARTISTIC CHARACTERISTICS<br />

OF NARRATIVE SINGING 170<br />

I. Labeled Piece-based Narrative Singing 170<br />

II. Narrative Singing: Gushu (Drum Songs) 203<br />

III. The Art of Narrative Singing of Ethnic Minorities 256<br />

CHAPTER IV MUSIC OF CHINESE OPERA (XIQU)<br />

● SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 269<br />

I. Definition of <strong>Music</strong> of <strong>Chinese</strong> Opera (Xiqu) 269<br />

II. Historical Evolution of Xiqu <strong>Music</strong> 274<br />

III. Position of Xiqu Art in <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> Culture 279<br />

● SECTION 2 CATEGORIES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF<br />

XIQU MUSIC 282<br />

I. Classification of Xiqu <strong>Music</strong> 282

Contents<br />

XVII<br />

II. Four Major Xiqu Melodic Types and Their Characteristics 287<br />

III. Introduction to Selected Emerging Regional Xiqu Genres 353<br />

CHAPTER V INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC<br />

● SECTION 1 OVERVIEW 377<br />

I. Definition of Instrumental <strong>Music</strong> and the Concept of Yuezhong<br />

(<strong>Music</strong> Genre) 377<br />

II. Historical Evolution of Instrumental <strong>Music</strong> 379<br />

III. The Roles of <strong>Chinese</strong> Instrumental Ensembles in <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

<strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 393<br />

● SECTION 2 SOLO AND ENSEMBLE GENRES AND THEIR<br />

CHARACTERISTICS 395<br />

I. Types of Solo <strong>Music</strong> and Their <strong>Music</strong> Characteristics 395<br />

II. Major Types of Ensemble <strong>Music</strong> and Their Artistic Characteristics 454<br />

REFERENCES<br />

● CONTINUING READING MATERIALS 527<br />

● SOUND RECORDINGS FOR LISTENING AND ANALYSES<br />

RELATED TO EACH CHAPTER 529<br />

APPENDIX<br />

● GLOSSARY OF CHINESE TERMS 533<br />

● ABOUT AUTHORS AND TRANSLATORS 646

INTRODUCTION<br />

I. Long History of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture<br />

The musical culture in China has a long history. This is not surprising, as the country<br />

has a written history over 5000 years, and its history of music culture can be traced<br />

even further, a piece of solid evidence being the some 20 bone flutes excavated at the<br />

tomb of Neolithic Age Site in Jiahu Village, Wuyang County, Henan Province during<br />

1986 to 1987. The flutes are sophisticated, made to a high standard, with unified<br />

shape and structure. The hollow pipe body measures about 20 cm in length, carved<br />

with 7 holes (with an additional small hole at the back). After a trial performance and<br />

acoustic test, the most intact bone flute (M282: 20) can emit accurate pitches of the<br />

heptatonic scale; five of these instruments can produce a complete pentatonic scale.<br />

These flutes dated back to 7000 to 8000 years based on Carbon-14 dating tests, that<br />

is, the same age as Neolithic culture. Hence, the discovery of the bone flutes is the<br />

earliest tangible proof of the origin of music culture in China. The precious legacy<br />

from early history also includes over 160 bone flutes unearthed at Hemudu Site,<br />

Yuyao County, Hangzhou Bay, Zhejiang Province. These instruments are of different<br />

shapes and designs, and of different sizes. It is possible to conclude that they bear<br />

rudimentary features of three structures, namely open, close and retractable pipes,<br />

after thorough study of the positions of sound holes, blow holes, and the principle<br />

of sound production. This indicates that, in China, as early as seven millennia ago,<br />

there was a good understanding of various principles of making and performing wind<br />

instruments.<br />

Fig. 1. The bone flutes excavated at the tomb of Neolithic Age site in Jiahu Village, Wuyang County,<br />

Henan Province (used with licence)

2 INTRODUCTION<br />

Dating back three millennia to the Shang Dynasty, the character “ (yue, music)”<br />

was found inscribed on oracle. The diagrammatic features can be interpreted as a<br />

stringed instrument resting on a wooden stand. In the ensuing Zhou Dynasty some<br />

2500 years ago, Confucius was believed to have compiled the classic of poetry<br />

Shijing (Book of Songs), which contains 305 sung poetry, and can be considered as the<br />

oldest extant <strong>Chinese</strong> songs. These were believed to be sung to an accompaniment.<br />

From the verse structure, it is possible to distinguish over ten music forms, and these<br />

provide the basis for study of <strong>Chinese</strong> music. The advent of Book of Songs marks<br />

the early effort of folk song collection and collation in China. The social and cultural<br />

life inherent in the texts is the beginning of realism in literature and art in China, and<br />

they have a significant impact on the development of music and literature of later<br />

generations.<br />

The long history of bell-chimes dating back to pre-Qin period in the third century<br />

B.C. is a unique feature of music culture in China, showing on the one hand the<br />

great advancement of bronze casting technology, and on the other hand the pinnacle<br />

of the theory of temperament and acoustic science in general. In the late Western<br />

Zhou Dynasty (1045–771 B.C.), the number of bells included in a set had developed<br />

from three or five to eight pieces. The famous set of bell-chimes unearthed at tomb<br />

of Marquis Yi of Zeng of the Warring States Period in Sui County (present Suizhou<br />

City), Hubei Province in 1978 comprises 64 regular bells and a Bo (large bell of<br />

distinct shape). The finding has generated much interest in archaeological research<br />

in organology, since the bells are the largest and most complete set of <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

Fig. 2. The set of bell-chimes unearthed at tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng of the Warring States Period<br />

in Sui County (present Suizhou City), Hubei Province

Long History of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 3<br />

tuned percussion instruments so far. The bell chimes cover a range of three octaves<br />

chromatically. In addition, the bells are cast with temperament inscriptions and other<br />

texts of over 2,800 ancient <strong>Chinese</strong> characters. There is a feeling amongst <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

scholars that the music treasure buried over 2400 years has become the testimony of<br />

one aspect of advanced development of <strong>Chinese</strong> music culture in ancient times.<br />

The <strong>Chinese</strong> believe that music is a composite art, meaning that a performance<br />

usually comprises singing, instrumental playing, dance or acrobatics. In other<br />

words, it is often difficult to single out one aspect of performance. Hence in the Han<br />

Dynasty, when a new art form known as Xianghe 1 appeared, it encompasses songs,<br />

dance, acrobatics and instrumental performance, and the genre later developed to<br />

folk songs in Eastern and Western Han, Wei and Jin Dynasties. Songs in the Han can<br />

be divided into two kinds, namely Xianghe’ge and Xianghe Daqu according to style<br />

and context of performance. Xianghe’ge refers to the songs and ballads “sung in<br />

streets”, that is, folk songs. These were first performed in style of Tuge (bare songs),<br />

sung unaccompanied, and they were also known as Dange; these songs were later<br />

performed with instrumental accompaniment. The singer usually holds a clapper to<br />

mark the tempo, while the accompaniment may include Di bamboo flute, Sheng mouth<br />

organ, Qin zither, Pipa lute and Zheng zither. Xianghe Daqu is a kind of large-scale<br />

combined art form featuring songs, dance and music, developed from Xianghe’ge; the<br />

former is performed as a kind of suite, and sections are organized according to certain<br />

type of structure. When the instrumental part is played independently, the music is<br />

called Danqu. After the Sui and Tang Dynasties, Xianghe Daqu was incorporated<br />

into Qingyue Daqu with a new outlook. There was a general recognition of the value<br />

of wind and drum music of Xianghe, and it had an important role to play in the<br />

development of ceremonial music.<br />

<strong>Music</strong> of western regions had a profound influence during the Sui and Tang<br />

Dynasties, and various genres, including those developed amongst ethnic minorities,<br />

began to have a more marked influence on Han music of central regions. The music<br />

records in Suishu (Annals of Sui) and Jiu Tangshu (Old Annals of Tang) include<br />

detailed descriptions of ensembles from western regions performed at court, which<br />

included seven categories. For example, the description of Tianzhu music (from<br />

India) refers to costumes of the musicians as monk’s gowns, inferring to ceremonial<br />

Buddhist music; Qiuci music describes music of ancient Kucha (Qiuci), or present<br />

Kuche County, Xinjiang, and it was considered the most influential type of foreign<br />

music (Hubu’yue) at the Tang court; Xiliang music, originally known as Qinhan<br />

music, developed from Han music in central regions by absorbing local Qiuci music<br />

and folk music of northwest regions, and Xiliang music assumed a prominent position<br />

at the <strong>Chinese</strong> court for many generations; Gaochang music originated from the<br />

present Turpan of Xinjiang, and the music ensemble was established after Emperor<br />

Taizong of Tang ascended to the throne; Kangguo music is originated near Samarkand<br />

in Central Asia, the most outstanding feature being Whirling Dance (Huxuan’wu);<br />

1 相 和

4 INTRODUCTION<br />

Anguo music has links with music of the present Bukhara of Central Asia; Shule music<br />

was music performed in present Shule and Yengisar areas of Xinjiang. While the<br />

music of these genres is lost, the detailed description of the instrumental ensembles<br />

throws some light on the acculturation that has been taking place.<br />

In addition to influence of music from ethnic minorities of west regions,<br />

important music genres of the Sui and Tang Dynasties included Yanyue (Ancient<br />

Court Entertaining <strong>Music</strong>), Faqu (Buddhist <strong>Music</strong>), Guchui’yue (Wind-and-Drum<br />

<strong>Music</strong>) and Guqin zither music. Yanyue refers to a kind of composed songs under the<br />

influence of Qingyue (Han <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong>), while Huyue (<strong>Music</strong> of Ethnic Minorities)<br />

was one of the six types of Zuobu’ji (Seated Performing Section) of the Tang court;<br />

Faqu originated in the Sui Dynasty, and it was further developed in the Tang Dynasty.<br />

It was a kind of song and dance Daqu (Composite <strong>Music</strong>) built on <strong>Chinese</strong> folk music<br />

while absorbing foreign music; Guchui’yue (Wind-and-Drum <strong>Music</strong>) of Tang court<br />

had many opportunities to develop. According to the instruments used in different<br />

performing contexts, the genre could be divided into Wind-and-Drum <strong>Music</strong> Section<br />

(Guchui’bu), Ritual <strong>Music</strong> Section (Yubao’bu), Cymbals-and-Wind <strong>Music</strong> Section<br />

(Naochui’bu), Big Horizontal Flute <strong>Music</strong> Section (Da Hengchui’bu) and Small<br />

Horizontal Flute Section (Xiao Hengchui’bu).<br />

Gewu Daqu (Song-and-Dance Composite <strong>Music</strong>) assumed an important position<br />

in the Sui and Tang Dynasties. The genre is based on large-scale musical form, and<br />

huge varieties of instrumentation facilitated by rapid development of the art of making<br />

instruments, resulting in music of grand scale. Gewu Daqu has much influence on<br />

music of East and Southeast Asia.<br />

<strong>Music</strong> for Pipa (four-stringed pear-shaped lute) became very fashionable in the<br />

Sui and Tang Dynasties. In spite of its ethnic origin from western regions, Pipa music<br />

developed much, as it was performed at court as well as used as a folk instrument,<br />

undergoing Sinicization, and being enriched by improved techniques of instrumental<br />

making and performing skills. The art of Guqin zither (or simply Qin) also developed,<br />

with the emergence of famous Guqin musicians such as He Ruobi, Zhao Yeli, Dong<br />

Tinglan, Xue Yijian and Chen Kangshi, who had made extraordinary contributions<br />

and had far-reaching influence; many songs and Qin compositions are still extant,<br />

thanks to the discovery of Guqin notation, which had further helped the preservation<br />

and dissemination of its music. The earliest extant Guqin notation is a rather lengthly<br />

text notation in the Tang Dynasty recorded by Liang Qiuming of the Southern Dynasty<br />

(494~590 AD), entitled Jieshi’diao Youlan (Secluded Orchid in Jieshi Mode). During<br />

the Sui and Tang Dynasties, Zhao Yeli, Chen Zhuo, Cao Rou and other Qin musicians<br />

reformed Guqin text notation, and finally discovered the Jianzi notation (abbreviated<br />

characters notation). This special notation of Guqin is still in use today. The Qin<br />

making technology reached unprecedented height in the Tang Dynasty. The Lei family<br />

in Sichuan was famous for Qin making, Lei Wei being the most famous. Shen Liao<br />

and Zhang Yue from south of the Yangtze River were “master players of Qin” in the<br />

period.<br />

Narrative singing took its shape in the Tang Dynasty and was marked by Bianwen

Long History of <strong>Traditional</strong> <strong>Chinese</strong> <strong>Music</strong> Culture 5<br />

(Changing Scriptures) and Jiangchang (Storytelling and Singing) in the temples.<br />

In the Song Dynasty, Ci poem music (Ciyue) and Guqin music were most<br />

important. Ci poem music is a vocal genre sung to Ci poem, and the core music<br />

materials dated back to the Sui and Tang Dynasties. During the later part of the<br />

Tang dynasty, the literati were more involved in writing song texts, therefore greatly<br />

improving the artistic value of Ci. By the way, Ci was a popular literary genre during<br />

the Five Dynasties, and it reached its heyday in the Song Dynasty. Structurally<br />

Ci has a structure comprising long and short verses, and such flexibility allows<br />

juxtapositioning between texts according to the length, and the twists and turns of the<br />

tune. Cipai (poetic labels set musically) has a framework, its feature being “structure<br />

with sentence pattern; a sentence with word pattern, and a word with sound pattern.”<br />

Cipai includes Ling, Jin and Man categories based on its length. In Ciyuan (Origin<br />

of Ci ) written by Zhang Yan, there is a reference to Yang Zuan’s Zuoci Wu’yaosu<br />

(Five Elements for Ci Creation), which states that the first step is to choose a tune,<br />

second is to set a tempo, third is to juxtapose words with music, fourth is to rhyme,<br />

and the last is to introduce new ideas. Yang’s idea of Ci is therefore not limited to<br />

the literary aspect, but rather encompassing creativity in music. Ci music therefore<br />

refers to art songs in ancient China, and it has absorbed ethnic and foreign music, in<br />

addition to folk music. Folk musicians and literati also created new form of this music<br />

genre, known as Ziduo’qu (self-composed song). The famous Baishi Daoren Gequ (A<br />

Song Collection by Baishi Daoren) by Jiang Kui (whose pen name is Baishi Daoren)<br />

includes music notations along Ci music, which had enabled scholars of many<br />

generations to investigate an authentic style of performance.<br />

In addition to Ci poem music, Guqin zither music developed much in the Southern<br />

Song Dynasty, which also led to everlasting influence in the history of <strong>Chinese</strong><br />

music. Famous masters of the Guqin of the period included Guo Mian (literary name<br />

Chuwang, c.1190–1260 AD), and he was recognized for his interpretation of famous<br />

pieces such as Xiaoxiang Shuiyu (Mist and Clouds over Xiaoxiang Lake), Fan<br />

Canglang (Waves Coming Over) and Qiuhong (Autumn Geese); Liu Zhifang was<br />

remembered for his famous pieces Wangji (Empty Mind) and Wujiang’yin (The Song<br />

of Wujiang River); Mao Minzhong was highly regarded for his famous pieces Yuge<br />

(Fisherman Song), Qiaoge (Song of Woodcutter) and Peilan (Having Orchid).<br />

During the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, opera and narrative music came into limelight.<br />

The former genre mainly includes Zaju (Miscellaneous Dramatic Performances) and<br />

Nanxi (Southern Opera), while the latter refers to Zhugong’diao (Tunes in Multiple<br />

Modes).<br />

In the Northern Song Dynasty, Zaju (Miscellaneous Dramatic Performances)<br />

was a general term for different formats of performance, such as farce, puppet show,<br />

shadow puppets, narrative singing, song-and-dance, acrobatics and martial arts, but<br />

it can also refer to a special kind of operatic performance. In the ensuing Southern<br />

Song Dynasty, there was an understanding that “only Zaju is idiomatic” 2 . Zaju was,<br />

2 From Ducheng Jisheng (Records of the Capital), written by Nai Deweng in the Southern Song Dynasty.