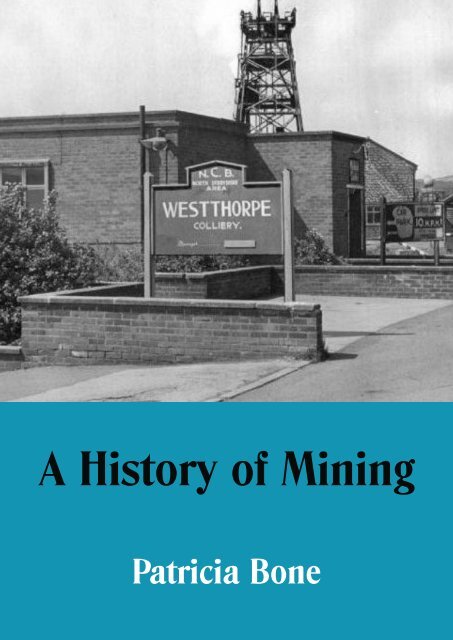

A History Of Mining by Patricia Bone

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong><br />

<strong>Patricia</strong> <strong>Bone</strong>

This book is dedicated to Eric Marshall, my Dad,<br />

who would have encouraged and supported me.<br />

Produced <strong>by</strong> Killamarsh Heritage Society<br />

Book design and graphics <strong>by</strong> Nick Wallace<br />

www.thedoorsteppa.com<br />

Printed and bound in Great Britain <strong>by</strong> Acorn Press Ltd<br />

www.acornpress.co.uk

CONTENTS<br />

4 Introduction<br />

CHAPTER ONE<br />

THE HISTORY<br />

OF MINING<br />

5 The <strong>History</strong> of Coal<br />

6 Pit Ponies<br />

7 The Life and Times<br />

of Jem The Pit Pony<br />

9 Women and Children<br />

Working in Mines<br />

10 The Much Needed<br />

Introduction of<br />

Legislation<br />

13 The Pit Brow Lasses<br />

CHAPTER THREE<br />

REMEMBERING<br />

WESTTHORPE<br />

COLLIERY<br />

38 The <strong>History</strong> of<br />

Westthorpe Colliery<br />

- 1923 - 1984<br />

39 The Managers at<br />

Westthorpe Colliery<br />

40 Westthorpe<br />

Collieries Day of<br />

Fame<br />

41 The Record Breakers<br />

42 The Pit Mascot<br />

51 The West End Hotel<br />

52 The Der<strong>by</strong>shire<br />

Miners Convalescent<br />

Home<br />

53 Holbrook and<br />

Westthorpe St John<br />

Ambulance Brigade<br />

54 The Pit Explosion<br />

57 A Love of Sports<br />

58 The Miners Strike<br />

1984-1985<br />

59 My Memories of<br />

being a Westthorpe<br />

Colliery Miner<br />

60 The Westthorpe<br />

Colliery Memorial<br />

15 Truck and the<br />

Miners - The Truck<br />

Act 1831<br />

16 The many collieries<br />

in Killamarsh<br />

17 The Davy Lamp<br />

17 A Miner’s Snap<br />

18 The Underground<br />

Front -<br />

Remembering<br />

The Bevin Boys<br />

22 Nationalisation -<br />

1947<br />

CHAPTER TWO<br />

WESTTHORPE<br />

COLLIERY<br />

IN PICTURES<br />

24 A selection of<br />

photographs of<br />

Westthorpe colliery<br />

over the years<br />

42 The Pit Hooter<br />

43 The Much Needed<br />

Pit Head Baths<br />

44 Westthorpe Colliery<br />

Canteen<br />

44 The Time and Wages<br />

<strong>Of</strong>ice<br />

45 The Telephone<br />

Exchange<br />

46 The <strong>History</strong> of the<br />

Pit Check<br />

48 Der<strong>by</strong>shire Miners<br />

Holiday Camps<br />

51 The Miss Westthorpe<br />

Competition<br />

CHAPTER FOUR<br />

THE COAL<br />

AUTHORITY TODAY<br />

61 The Coal Authority<br />

CHAPTER FIVE<br />

MINING POEMS<br />

62 Heaven or Hell?<br />

62 The Old Miner<br />

63 Proud Sarah<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

I would like to thank the following for<br />

their help and support in writing this book<br />

Killamarsh Parish Council, Lee Rowley MP, The Coal Authority, Nick Wallace,<br />

Acorn Press Ltd and Killamarsh Heritage Society. Thank you Westthorpe<br />

miners and their families for the information, their memories and photographs.<br />

Also Kevin <strong>Bone</strong> and Margaret Marshall for their moral support.<br />

And of course thank you to the many men and women who worked<br />

at Westthorpe Colliery during its history.

Introduction<br />

Killamarsh has a long and proud histor as a coal mining area, with coal being<br />

mined since at least the 15 th centr with many small pits being opened over the centries.<br />

Westthorpe Colliery opened in 1923 when the first sod was cut on the 17 th of<br />

March.<br />

During its lifetime the pit provided employment for many men and women and was<br />

successful in attaining many targets in coal production.<br />

Westthorpe Colliery played a huge part in the working and social lives of the people<br />

of Killamarsh and the surrounding villages and resulted in a very close community.<br />

Many ex-miners still live in Killamarsh and the surrounding villages although,<br />

of course, many are no longer with us.<br />

However, many of their children, grandchildren and great grandchildren still live in<br />

the area and for them the memory of Westthorpe Colliery should be kept alive.<br />

This is important to me as my Grandad, Dad, brothers, uncles and cousins all<br />

worked at Westthorpe pit during its life.<br />

So I decided to write this book to mark Westthorpe’s 100 year anniversary.<br />

Although I am not an historian, in the first part of the book I have tried to cover what<br />

miners had to endure in the past.<br />

The second part of the book remembers Westthorpe Colliery and I hope will bring<br />

back memories.<br />

I know everyone loves to see old photographs so I have included a section with<br />

photographs of Westthorpe which I feel don’t need an explanation for those who<br />

remember the pit so well.<br />

Everyone will have their own memories, reminiscences and recollections. And of<br />

course everyone has anecdotes.<br />

I have tried to make the book as accurate as possible but hope you will forgive any<br />

inaccuracies – to quote – recollections may vary.<br />

But most of all I hope you enjoy.<br />

<strong>Patricia</strong> <strong>Bone</strong><br />

Killamarsh Heritage Society<br />

2023<br />

4 Introduction

The <strong>History</strong> of Coal <strong>Mining</strong><br />

in the United Kingdom<br />

Coal, as we all know, is solid fel but millions of<br />

years ago the world had no coal reseres.<br />

So where did it come om?<br />

345 to 280 million years ago, the world was mostly<br />

covered with a luxuriant vegetation which grew in<br />

swamps.<br />

A large number of these plants were types of fern, and<br />

some were as big as trees.<br />

This vegetation died off and became submerged under<br />

water. It gradually decomposed and as it decomposed,<br />

the vegetable matter lost oxygen and hydrogen atoms, it<br />

left a deposit which contained a high percentage of<br />

carbon.<br />

Peat was formed first, but over the years layers of sand<br />

and mud settled, from the water, over some of the<br />

peat. Pressure from the layers above, the movements of<br />

the earth's crust, plus at times volcanic heat,<br />

compressed and hardened the deposits.<br />

Through this process coal was formed.<br />

In some areas of Britain, evidence has been discovered<br />

that indicates stone-age inhabitants collected and used<br />

coal.<br />

Flint axes have been found embedded in layers of coal<br />

in excavations at Monmouthshire and Stanley in<br />

Der<strong>by</strong>shire. Excavations frequently turn up the remains<br />

of coal fires, which the Romans used to fuel their<br />

heating systems.<br />

Up to the 18th century coal was only mined near the<br />

surface beside outcrops, this type of mining was known<br />

<strong>by</strong> the names, "bell pits" and "adit mines".<br />

In the 13th century a charter dealing with and<br />

recognising the importance of coal supplies was granted<br />

to the freemen of Newcastle, allowing them to dig for<br />

coals unhindered.<br />

Another method of mining were drift mines which<br />

were usually sunk into the hillside. The coal seam was<br />

usually visible at the side of the hill (known as outcrop<br />

coal). The coal was first removed from the side of the<br />

hill, then the miners had to follow the seam further and<br />

further underground, the coal was worked until the<br />

working conditions became unsafe. The mine was then<br />

abandoned.<br />

By 1683, some of the bigger mines were using timber<br />

to support the roof, this enabled coal to be mined<br />

much further away from the mine entrance.<br />

In 1832 deeper mines were using a technique which we<br />

know as:-<br />

(a) bord and pillar<br />

(b) pillar and stall<br />

(c) room and pillar<br />

(d) stoop and room.<br />

The name varied depending upon the part of the<br />

country the mining took place, however the method<br />

was basically the same.<br />

Coal was extracted from an area underground, (the<br />

'rooms', stalls etc.), pillars of coal were left in to support<br />

the roof. When a boundary was reached they began<br />

working their way backwards, removing the pillars on a<br />

retreat basis.<br />

<strong>Mining</strong> as we know it<br />

had arrived.<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 5

Pit Ponies<br />

As mines became larger there was more undergound haulage; boys aged 10 to 14<br />

were considered old enough to gide horses along the roadways.<br />

The horse pulled tubs of coal to the base of a hoist;<br />

where a 'gin', on the surface, completed the work of<br />

raising the coal to the surface. A 'gin' usually consisted<br />

of a horse going in a circle, and working a wheel that<br />

winds up or lets down various loads into the pit.<br />

They also transported wood and other supplies into<br />

the mine to the working places. Mines were now using<br />

a lot of wood to timber up the roadways.<br />

The first known recorded use of ponies underground<br />

in Great Britain was in the Durham coalfield in 1750.<br />

At one time, around 70,000 of the miniature horses<br />

worked underground, even living in stables in the pits<br />

and seeing daylight only once a year.<br />

A pit pony was a horse, pony or mule used<br />

underground in mines from the mid-18th until the<br />

mid-20th century. The term "pony" was broadly applied<br />

to any equine working underground .<br />

For protection they wore a skullcap and bridle made of<br />

leather. A pony had to be three years old before it was<br />

allowed down the pit. They learned to walk with their<br />

heads down and could open air doors in the roadway,<br />

and knew which door needed pulling and which doors<br />

it could push.<br />

In shaft mines, ponies were normally stabled<br />

underground and fed on a diet with a high proportion<br />

of chopped hay and maize and they came to the<br />

surface only during the colliery’s annual holiday. In<br />

slope and drift mines the stables were usually on the<br />

surface near the mine entrance.<br />

Typically, they would work an eight-hour shift each<br />

day, during which they might haul 30 tons of coal in<br />

tubs on the underground mine railway. In 1911, it<br />

was estimated that the average working life of coal<br />

mining mules was only 3½ years, whereas 20 year<br />

working lives were common on the surface.<br />

Prevention of Cruelty to Pit Ponies, Countess Maud<br />

Fitzwilliam, awarded a young Elsecar Colliery mine<br />

worker, John William Bell of Wentworth, the<br />

Fitzwilliam Medal for Kindness for an act of bravery<br />

that saved the life of his equine workmate. Bell’s story<br />

of staying behind while his human workmates were<br />

able to escape through a small opening, to ensure that<br />

the pony would have a chance of rescue, became a<br />

successful tool for the Countess in promoting pit pony<br />

rights.<br />

In 1911, Sir Harry Lauder became an outspoken<br />

advocate, “pleading the cause of the poor pit ponies”<br />

to Sir Winston Churchill, when introduced to him at<br />

the House of Commons, reporting to the Tamworth<br />

Herald that he “could talk for hours about my wee<br />

four-footed friends of the mine. But I think I<br />

convinced him the time has now arrived when<br />

something should be done <strong>by</strong> the law of the land to<br />

improve the lot and working conditions of the<br />

patient, equine slaves who assist so materially in<br />

carrying on the great mining industry of this<br />

country.”<br />

Pit ponies were used in mining to the late 20 th century.<br />

In 1913, at the peak, there were 70,000 ponies<br />

underground in Britain. In later years, mechanical<br />

haulage was introduced on the main underground<br />

roads replacing pony hauls, and ponies tended to be<br />

confined to the shorter runs from coal face to main<br />

road which were more difficult to mechanise. This<br />

dropped to 21,000 after the nationalisation of the<br />

mines in 1947.<br />

In 1984 there were still 55 ponies in use with the<br />

National Coal Board in Britain, chiefly at Ellington in<br />

Northumberland. The last pony left Ellington in 1994.<br />

The British Coal Mines Regulation Act 1887 presented<br />

the first national legislation to protect<br />

horses working underground. Due to pressure from<br />

the National Equine Defense League (formerly the<br />

Pit Ponies Protection Society) found in 1908 <strong>by</strong> animal<br />

and human rights advocate Francis Albert<br />

Cox – and the Scottish Society to Promote Kindness to<br />

Pit Ponies, in 1911 a Royal Commission report<br />

was published, detailing conditions, which resulted<br />

in protective legislation.<br />

In 1904, the president for the Association for the<br />

6 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

The Life and Times of<br />

Jem The Pit Pony<br />

At this time there was lile or no mechanisation in the mining indust as we<br />

know it today. So small ponies were bred specially to work in the small roadways<br />

in the early days of coal mining in the 20 th centr.<br />

At this time there was little<br />

or no mechanisation in<br />

the mining industry as we<br />

know it today.<br />

So small ponies were bred<br />

specially to work in the small<br />

roadways in the early days of<br />

coal mining in the<br />

20 th century.<br />

In those early days, conditions underground were very<br />

poor with many hazards, due to small, poorly<br />

supported roadways, water, dust and of course the very<br />

dangerous gas methane, which caused many explosions<br />

and consequently deaths.<br />

There were many fatalities for both men and animals.<br />

Safety at that time was not really a priority, the mine<br />

owners being more interested in the amount of coal<br />

brought to the surface and their profit.<br />

Men worked in seams that were not very thick and<br />

sometimes in very wet and hazardous conditions.<br />

It was even worse for the ponies who sometimes<br />

worked longer hours than the men and most never saw<br />

the sunshine and the light of day except for two weeks’<br />

when the mine ceased working for the annual two<br />

weeks holiday. Many died underground and were<br />

instantly replaced <strong>by</strong> others who were condemned to<br />

the same fate. Pit ponies to the mine owners were a<br />

very valuable asset, because obviously they didn’t need<br />

payment. They were worked until they were exhausted<br />

and when they were of no more use they would be<br />

brought to the surface and shot and possibly sold for<br />

dog meat.<br />

The stables for the ponies were very close to the<br />

bottom of the shaft and as you entered, it opened up<br />

into a square room which worked as a reception area.<br />

The harnesses were arranged on hooks fastened to the<br />

wall.<br />

Here the pony drivers first gathered to pick up their<br />

allocated charge and to make the pony ready for his<br />

work for the shift. Stored also in this room were sacks<br />

of feed, oats and associated grain and also in a corner a<br />

large container filled with water, sometimes clean and<br />

sometimes not so clean. From this room, led off to a<br />

corridor, which on either side were rows of stalls which<br />

housed the ponies, each with his name above the<br />

entrance.<br />

Jem was a sturdy pony with strong muscular legs, a<br />

brown chestnut coloured coat and mane with a white<br />

blaze on his forehead. When I first entered his stall I<br />

had to unhook his tether and then harness him ready<br />

for work. He had headgear and blinkers to protect<br />

him from low beams and the rest of his harness was<br />

arranged around his body to which was then attached a<br />

metal frame, called limmers which were used to attach<br />

him to empty and full coal tubs.<br />

Jem was very intelligent with an acute sense of hearing<br />

and other senses to match. I sometimes used to try to<br />

sneak into the stables <strong>by</strong> opening the door very slowly,<br />

but you could never fool him because his senses were<br />

so acute. They had to be because of the inherent<br />

dangers within the mine. The joy at seeing me at the<br />

start of the shift was unbelievable, he would whinny a<br />

welcome and would not quieten down until he had<br />

found <strong>by</strong> sniffing around my pockets for his morning<br />

treat, his favourite being a juicy red apple. There was<br />

always some treat for Jem, my large pockets usually<br />

contained sweets, lumps of sugar, carrots and other<br />

titbits as well.<br />

Pit ponies at this time were used extensively for a<br />

variety of difficult jobs but sometimes they were very<br />

badly ill-treated. At times I would see him before we<br />

commenced our shift covered in mud, all his legs and<br />

the underside of his body, because he had been<br />

working the previous night.<br />

I would never leave him in such a state. I would fetch a<br />

bucket of water and clean him of all the mud collected<br />

on him during the shift and make sure he was<br />

comfortable in his stall before I went home.<br />

I have mentioned before about their super senses.<br />

They could foresee danger long before human senses<br />

recognised there was danger imminent.<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 7

The Life and Times of<br />

Jem The Pit Pony (CONT.)<br />

There was always the incidents of roof collapse<br />

because of poor wooden support systems, and a pony<br />

pulling a set of full or empty tubs would suddenly stop<br />

and not move any further if he sensed the roadway in<br />

front was going to collapse. Sometimes they could be<br />

ill-treated to make them move forward but they still<br />

would not move.<br />

Nothing would induce them when they sensed danger.<br />

This sort of action has many times saved the lives of<br />

both men and animals.<br />

Such was the life, or should I say fate of Jem and all the<br />

other pit pones who lived and worked underground<br />

deep in the bowels of the earth.<br />

When some of the lucky ones were brought to the<br />

surface during the annual two weeks holiday and<br />

turned out into a field with all its views of the<br />

countryside and of course that lovely sweet green grass,<br />

it must have been such a wonderful feeling.<br />

Then, of course, after those wonderful two weeks they<br />

would be taken back underground and would never<br />

see the light of day again for another year.<br />

It was during 1939/1940, that I started working<br />

underground and these condition were as I have stated.<br />

The lamps we carried were heavy and gave only poor<br />

light. The ponies did not even have a light and had to<br />

rely on the one that the pony driver carried.<br />

In most circumstances they would actually lead the way<br />

and once they had got used to a certain area they<br />

would do it without an order.<br />

If they were treated properly, they would show their<br />

appreciation <strong>by</strong> the amount of work they achieved<br />

during the shift.<br />

They really were remarkable and sincere little animals.<br />

Alf Mather, <strong>Mining</strong> Engineer (Retired)<br />

8 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

Women & Children Working in Mines<br />

When we think back to the histor of mining, our minds oſten<br />

conjure up images of hardworking men covered in coal, working<br />

undergound. However, what we oſten don’t think about is the<br />

women and children who also worked in mining –<br />

and the roles they played.<br />

As the population in Britain increased, the need for<br />

fuel supplies also increased, wood became scarce as<br />

great tracts of forest were felled for both fuel and<br />

building materials.<br />

In the early coal industry women and girls worked<br />

underground alongside men and boys in small coal<br />

pits. This was common practice in Lancashire,<br />

Cumberland, Yorkshire, the East of Scotland and<br />

South Wales.<br />

From the 1600s in Lancashire it was common for<br />

whole families to be employed in the pits. Colliers<br />

relied on their wives, sons and daughters who were<br />

employed as drawers. The daughters of colliers usually<br />

married within the mining community. As the industry<br />

grew the population expanded and more members of<br />

extended mining families obtained work. Pit work in<br />

South-West Lancashire resulted in the area around<br />

Wigan having the highest rates of female employment<br />

in the country in the 19 th century.<br />

It is difficult for us to believe or understand, but<br />

children of all ages were used in the coal mines, as<br />

soon as a child was seen as old enough to help, the<br />

child began work.<br />

Children as young as five worked at jobs that were<br />

dangerous and exhausting.<br />

For a child going underground for the first time the<br />

mine would be a very scary place, it was pitch black, a<br />

candle or an oil lamp was all the illumination a child<br />

would have, if the candle went out or the oil ran out<br />

they could spend hours in complete darkness. During<br />

that time they would hear all sorts of noises, strata<br />

moving, pieces of roof or sides falling, and rats were<br />

common in the mines, so they would hear them<br />

scurrying around them. Children were on average five<br />

times cheaper to employ than adults and were<br />

expected to work the same hours which could mean a<br />

14-hour day.<br />

One of their first jobs would be as a trapper. A trapper<br />

is stationed at traps (canvas flaps) or doors in various<br />

parts of the pit, the trapper opened the trap so that<br />

trams of coal could pass through, then they<br />

immediately closed it again when the trams had passed<br />

through the trap. Air ventilation was stringently<br />

controlled and if the trap was not closed correctly, parts<br />

of the mine would lack adequate ventilation and<br />

dangerous gases would<br />

build up.<br />

Another job for children<br />

was as a carter. They<br />

used to drag carts loaded<br />

with coal from the coal face to the<br />

main road, a distance of sixty yards. The carts had no<br />

wheels. Leather belts were placed on the child's<br />

shoulders, the child had to drag the coal with ropes<br />

over their shoulders.<br />

Trappers kept the airflow going which stopped the<br />

build-up of dangerous gases. Drawers dragged<br />

truckloads of coal to the surface. Older children<br />

operated the mine shaft pulleys.<br />

The older children were employed as hurriers, pulling<br />

and pushing tubs full of coal along roadways from the<br />

coal face to the pit-bottom.<br />

The younger children worked in pairs, one as a<br />

hurrier, the other as a thruster, but the older children<br />

worked alone.<br />

Many women and children were employed below<br />

ground. Mine owners employed women as they were<br />

able pay them half a man’s wage. In 1841 2,350<br />

women were employed in coal mines – in a variety of<br />

roles. Although women are often thought to have only<br />

worked at the surface of mines, women did in fact<br />

often hold roles that required them to work<br />

underground.<br />

In 1842, the Mines and Collieries Act banned females<br />

of any age from working underground and required<br />

boys who worked underground to be no younger than<br />

ten years old.<br />

The Mines Act, as it was commonly known, was<br />

passed in 1842, as a result of Lord Shaftesbury’s report<br />

into the employment of women and young children in<br />

coal mines. The law stopped all females and children<br />

under 18 years of age from working underground. From<br />

1843 the act was extended so that all women had to stop<br />

working underground. For many mining families, the loss<br />

of income from these working women was a disaster.<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 9

The Much Needed Introduction<br />

of Legislation<br />

Miners were fired <strong>by</strong> a sense of solidarit, but also <strong>by</strong> dangerous<br />

working conditions, which resulted in high death and injur rates.<br />

In parallel with factories, mills and workshops,<br />

Victorian legislators responded to concern about<br />

working conditions in coal mines, especially the<br />

employment of women and children.<br />

In the 1830s there was a movement towards social<br />

reform, especially towards the employment of<br />

children in the burgeoning industries in England. In<br />

1833 Parliament introduced the Factory Act which<br />

prevented the employment of children under nine<br />

from working in textile mills. Following this was a<br />

campaign to offer similar protection to children, and<br />

women, employed below ground in mines.<br />

It is believed that the general British public learned<br />

for the first time that women and children worked in<br />

the mines, following reports of an accident in a coal<br />

mine in 1838 in Barnsley. After violent<br />

thunderstorms, a stream overflowed into the mine’s<br />

ventilation system and 26 children - 11 girls and 15<br />

boys (some as young as 8 -years old) were<br />

accidentally drowned.<br />

The London papers reported this and there was a<br />

public outcry. It came to the attention of Queen<br />

Victoria who put pressure on the Prime Minister to<br />

hold an inquiry into the working conditions of<br />

women and children in mines and factories. Charles<br />

Dickens also expressed his concern after visiting<br />

mines for himself.<br />

As a result, in 1840, Parliament established the Royal<br />

Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment<br />

in Mines. The Commission was headed <strong>by</strong> Anthony<br />

Ashley Cooper, the 7 th Earl of Shaftesbury, with a<br />

report compiled <strong>by</strong> Richard Henry Horne, a friend<br />

of Charles Dickens and sometime contributor to<br />

Dickens’ Daily News.<br />

The result of a three-year investigation into working<br />

conditions in mines and factories in England, Ireland,<br />

Scotland and Wales, the Report of the Children’s<br />

Employment Commission is one of the most<br />

important documents in British industrial history.<br />

Comprising thousands of pages of oral testimony<br />

(sometimes from children as young as five), the<br />

report’s findings shocked society and swiftly led to<br />

legislation to secure minimum safety standards in<br />

mines and factories, as well as general controls on the<br />

employment of children.<br />

The Commission report probably helped make a<br />

decisive impact on Victorian Society.<br />

Between 1838 and 1841, 28 children had died in the<br />

Halifax, Huddersfield and Low Moor coal mines.<br />

Women and children were regularly employed in<br />

mines in the area.<br />

As part of the Royal Commission of Inquiry, an<br />

investigation was carried out <strong>by</strong> Sub-Commissioner<br />

Samuel Scriven iin the Halifax, Huddersfield and<br />

Bradford areas.<br />

Mr Scriven used a different method to other<br />

inspectors in different areas <strong>by</strong> interviewing the<br />

children and miners. This enabled him to get a<br />

much more detailed look into their lives. He was<br />

helped in Halifax <strong>by</strong> local Surgeon James Holroyd<br />

who knew the local mine and mill owners well.<br />

Scriven interviewed the miners and children inside<br />

the mines, wearing suitable clothing and talked to<br />

them when they were on their limited rest breaks.<br />

Sometimes he would crawl in tunnels just 20 inches<br />

tall.<br />

He was shocked <strong>by</strong> the adult miners’ appearance<br />

when working naked and that they were ‘mashed up’<br />

<strong>by</strong> the physical work <strong>by</strong> their 40s. The children<br />

interviewed <strong>by</strong> Scriven in Halifax tended to be<br />

muscular but stunted in growth, which Scriven<br />

attributed to ‘severe labour exacted from them during<br />

a period of infancy and adolescence’. Both girls and<br />

boys did identical work, the girls often as ‘vulgar’ and<br />

‘obscene in language’ as the boys.<br />

Sub-Commissioner Scriven went into a shaft in<br />

Staffordshire in 1841 expecting to find a place of<br />

work. Instead, he descended into hell.<br />

Quite apart from the children who laboured in<br />

dangerous conditions, men and women worked side<strong>by</strong>-side,<br />

stripped to the waist and sweating furiously in<br />

the heat. There was “something truly hideous and<br />

Satanic about it,” Scriven said - not least because<br />

some of the women, if they weren’t completely<br />

naked, were wearing trousers.<br />

10 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

This, along with their bare breasts was an affront to<br />

Victorian modesty. These young women would be<br />

“unsuitable for marriage and unfit to be mothers.”<br />

The Labour Tribune, which called itself the “Organ<br />

of the Miner,” went further still saying: “A woman<br />

accustomed to such work cannot be expected to<br />

know much of household duties or how to make a<br />

man’s home comfortable.”<br />

Trousers were shocking. The Manchester Guardian<br />

called them “the article of clothing which women<br />

ought only to wear in a figure of speech”, the Daily<br />

News claimed that the “habitual wearing of the<br />

costume tends to destroy all sense of decency,” and<br />

even the Miners’ Union said they were a “most<br />

sickening sight.”<br />

But women miners had few options when it came to<br />

clothing: flimsier, cooler clothing, which revealed the<br />

contours of their body, were seen as “an invitation to<br />

promiscuity.”<br />

Trousers and other practical garments were<br />

“unwomanly” – and often led to wardrobe<br />

malfunctions.<br />

In his 1842 speech to Parliament, Lord Ashley<br />

described how the work sometimes wore holes in the<br />

crotch of these women and girls’ trousers:<br />

underground work for women and girls, and for boys<br />

under 10.<br />

In 1842 a report <strong>by</strong> the Royal Commission<br />

on the employment of women<br />

and children in mines caused<br />

widespread public dismay at<br />

the depths of human degradation<br />

that were revealed.<br />

Owners showed a critical<br />

lack of concern or responsibility for<br />

the welfare of the workers.<br />

Further legislation in 1850 addressed the frequency<br />

of accidents in mines. The Coal Mines Inspection<br />

Act introduced the appointment of Inspectors of<br />

Coal Mines, setting out their powers and duties, and<br />

placed them under the supervision of the Home<br />

<strong>Of</strong>fice.<br />

The Coal Mines Regulation Act of 1860 improved<br />

safety rules and raised the age limit for boys from 10<br />

to 12.<br />

He said: “The chain passing high up between the legs<br />

of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers.<br />

Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can<br />

scarcely be imagined than these girls at work. No<br />

brothel can beat it”.<br />

This shook the prudish Victorian society, and<br />

resulted in women being banned from working<br />

underground, not because of safety, but because ‘it<br />

made girls unsuitable for marriage and unfit to be<br />

mothers.’<br />

Having women in the mines was financially<br />

advantageous to both their bosses and their families.<br />

One “underlocker” told the Commission that women<br />

were paid roughly half of what men were, allowing<br />

their employer, the Collier, to spend “one shilling to<br />

one shilling and sixpence more at the alehouse”.<br />

It was common for children aged eight to be<br />

employed, but they were often younger. In mines in<br />

the east of Scotland girls as well as boys were put to<br />

work. In order to reinforce its message to MPs, the<br />

Commissioners Report was graphically illustrated<br />

with images of women and children at their work.<br />

The Mines and Collieries Bill, which was supported<br />

<strong>by</strong> Anthony Ashley-Cooper, was hastily passed <strong>by</strong><br />

Parliament in 1842. The Act prohibited all<br />

The Result of the Inquiry<br />

The outcome of the Inquiry was swift. As a result of<br />

the report, politician and reformer Anthony Ashley<br />

Cooper introduced the Mines and Collieries Act on<br />

the 4 th of August 1842 to Parliament and from 1 st<br />

March 1843 it became illegal for women, girls and<br />

boys under 10 (later amended to 13) from working<br />

underground in Britain.<br />

There was no compensation for those made<br />

unemployed which caused much hardship. This led<br />

to the widespread use of horses and ponies in<br />

mining, though child labour lingered on to varying<br />

extents until finally eliminated <strong>by</strong> a variety of factors<br />

including further laws, improved inspection regimes<br />

and changing economics.<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 11

The Much Needed Introduction<br />

of Legislation (CONT.)<br />

The Result of the Inquiry (CONT.)<br />

The Royal Commission 1840 focused on children,<br />

but it was women and girls who were most<br />

immediately affected <strong>by</strong> the report, which led to the<br />

exclusion of all women and girls from British mines.<br />

The 1842 Mines and Collieries Act banned all<br />

women and children under the age of 10 from<br />

working underground. No-one under 15 years was to<br />

work winding gear in mines. Families felt this sudden<br />

loss of income acutely.<br />

One female miner said afterwards, that though<br />

working underground was not pleasant, it was<br />

certainly better than starving.<br />

The Government appointed a civil servant, Hugh<br />

Tremenheere, to be the first Inspector of Mines. A<br />

barrister with no experience of mining, he had 2,000<br />

pits to oversee and no powers, but he secured<br />

compliance with the Act in four years.<br />

The prohibition of underground female labour<br />

caused much suffering and hardship and was greatly<br />

resented. The employment of women did not end<br />

abruptly in 1842, with the connivance of some<br />

employers, women dressed as men continued to<br />

work underground for several years.<br />

Penalties for employing women were small and<br />

inspectors were few and some women were so<br />

desperate for work they willingly worked illegally for<br />

less pay.<br />

Also children continued working underground at<br />

some pits. At Coppull Colliery’s Burgh Pit, three<br />

females died after an explosion in November 1846,<br />

one was eleven years old.<br />

The Mines Act may have stopped women from<br />

working underground, but did not forbid girls and<br />

women from working on the surface of the mine and<br />

many women continued to work in the Pits.<br />

However, not all women who had worked<br />

underground gained employment as surface workers.<br />

Lighter work on the surface had been reserved for<br />

older men and men who had been injured below<br />

ground and some colliery owners considered pits<br />

unsuitable places for women.<br />

Other colliery owners were happy to employ women<br />

who had proved themselves reliable and strong<br />

workers and were used to the language and habits of<br />

the miners.<br />

But <strong>by</strong> 1860 hostility to employing women became<br />

more apparent. Many men working in cotton mills<br />

were out of work because of the cotton famine<br />

during the American Civil War and it was felt that<br />

women should not be doing jobs that could be filled<br />

<strong>by</strong> men.<br />

Once again the women came into the public<br />

consciousness, stimulated <strong>by</strong> reports of calls to ban<br />

them.<br />

In 1863 the National Miners’ Association resolved at<br />

its conference to ask the Government to prevent<br />

female employment in collieries.<br />

The proposal came from a Barnsley delegate, an area<br />

that was staunchly against employing women.<br />

It read: “The practice of employing females on or<br />

about the pit bank of mines and collieries is<br />

degrading to the sex, leads to gross immorality and<br />

stands like a foul blot on the civilisation and<br />

humanity of the kingdom”.<br />

Arthur Mun<strong>by</strong>, a Cambridge academic with an<br />

interest in women who worked in dirty and unusual<br />

conditions, commissioned many photographs and<br />

had visited the Wigan area many times over many<br />

years, interviewing working-class women and<br />

recording what they had to say about their jobs, pay<br />

and living conditions.<br />

Mun<strong>by</strong> described the women as lacking formal<br />

education, “rough and ready” in their ways and<br />

speech but not coarse, uncouth or immoral.<br />

By the 1880s, around 11,000 women had found work<br />

above ground at the coalmines, sorting coal.<br />

Conditions were cold and dirty, and so they wore a<br />

striking ensemble, as described <strong>by</strong> one onlooker:<br />

“She wears a pair of trousers which formerly were<br />

scarcely hidden at all, but are now covered with a<br />

skirt reaching just below the knees. Her head is<br />

bandaged with a red handkerchief, which entirely<br />

protects the hair from coal dust; across this is a piece<br />

of cloth which comes under the chin, with the result<br />

that only the face is exposed. A flannel jacket<br />

completes the costume.”<br />

The women famous for this outfit were known as the<br />

Pit Brow Lasses.<br />

12 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

The Pit Brow Lasses<br />

Fifty Shades of Black<br />

Pit brow lasses (in some areas known as pit brow<br />

women, pit head women) or tip girls were female<br />

surface labourers. They worked at the coal screens on<br />

the pit brow at the shaft top until the 1960s.Their job<br />

was to pick stones and sort the coal after it was hauled<br />

to the surface.<br />

Most pit brow women were unmarried and came from<br />

mining families. They often left pit work when they<br />

married and had families. They started work at six in<br />

the morning and worked either at screening tables or<br />

pushing coal tubs. The shifts were not the same as the<br />

men underground, as the coal was to be sorted when it<br />

reached the surface.<br />

A Pit Brow Wench for Me<br />

“I am an Aspull collier, I like a bit of fun<br />

To have a go at football or in the sports to run<br />

So good<strong>by</strong>e old companions, adieu to jollity<br />

For I have found a sweetheart,<br />

and she’s all the world to me<br />

Could you but see my Nancy,<br />

among the tubs of coal<br />

In tucked up skirt and breeches,<br />

she looks exceedingly droll<br />

Her face besmear’d with coal dust,<br />

as black as black can be<br />

She is a pit brow lassie,<br />

but she’s all the world to me”<br />

They worked outdoors and developed a distinctive<br />

mode of dress that was practical for the work involved<br />

but appeared strange to Victorian sensibilities and<br />

aroused considerable curiosity. They wore a distinctive<br />

‘uniform’ of clogs, trousers covered with a skirt and<br />

apron, old flannel jackets or shawls and headscarves to<br />

protect their hair from coal dust. Their<br />

unconventional, but practical dress drew them to the<br />

attention of the public and card portraits and later<br />

postcards of them in working clothes were produced<br />

commercially and sold as novelties<br />

But few other mines outside of Wigan had women<br />

customarily wearing trousers and seemed proud to<br />

have shaken of this moral affront. Scottish women<br />

miners were said to “dress like ordinary females, they<br />

do not dress like the Wigan ladies,” while<br />

the inspector for South Wales described the local<br />

women there as “respectably dressed.”<br />

But the pit brow women didn’t seem to be especially<br />

unhappy about their costume. They had other<br />

considerations to worry about, like feeding their<br />

families on half the wage that the men received.<br />

Many married male miners and were part of a tightknit<br />

local community, and even sparked the anonymous<br />

poem, “A Pit Brow Wench for Me”. (See Poetry<br />

section).<br />

Many pit brow lasses were very much in favour of<br />

being allowed to work in and around coal mines,<br />

choosing to sort coal above the surface, as opposed to<br />

working in mills or factories which were stuffy and<br />

unsanitary, and workplace accidents were almost as<br />

common.<br />

These women shocked some parts of Victorian society,<br />

and were seen <strong>by</strong> some as the prime example of<br />

degraded womanhood. But even though many thought<br />

of them as unladylike, they did what they<br />

By Anon<br />

could to assert their femininity in the pit among the<br />

dirt and dust. A French visitor described their “taste<br />

for feminine things and a love of ribbons, most of<br />

them, in fact wore ties around their neck, whose folds<br />

will soon become nothing more than little nests of coal<br />

dust.”<br />

There was a lot of camaraderie amongst the pit brow<br />

lasses, it even being suggested that they enjoyed it.<br />

Making the best of it was probably the best way to<br />

describe it. The women still needed to prepare food<br />

and carry out household chores. Dust and dirt were a<br />

constant menace. Life was described as a ‘turn’ at<br />

work then a ‘turn’ at home.<br />

Women were viewed as unskilled and were required<br />

to do additional jobs, such as cleaning the Manager’s<br />

office and even his home. Pit women were not<br />

encouraged to join in any of the men’s recreational<br />

activities. When not at the Colliery they spent their<br />

time with each other, with neighbours and close<br />

relatives, often helping each other. This ‘bonding’<br />

would explain why, when needed, they were so good at<br />

organising and supporting the men during the troubled<br />

times.<br />

The Fight Continued<br />

An even greater threat to women’s continuing<br />

employment emerged with a clause prohibiting the<br />

employment of women in the Mines Regulation Bill in<br />

1886. The 1,400 women working on the pit brow in<br />

the Wigan area received support from across the<br />

country. A meeting of support for the pit brow<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 13

The Pit Brow Lasses (CONT.)<br />

women called <strong>by</strong> the Reverend<br />

Fox at St Peter’s Church in<br />

Bryn near Wigan was attended<br />

<strong>by</strong> two hundred women and<br />

letters of support from the<br />

clergy, the nobility and others<br />

were read. Lord Crawford of<br />

Haig Hall wrote that he did<br />

not consider the pit girls were<br />

immoral and that their<br />

clothing, “the inheritance of<br />

their mothers and<br />

grandmothers”, was only<br />

objected to <strong>by</strong> “ignorant<br />

prudes”, who, if left along<br />

would probably put a “frill”<br />

round the ankles of their<br />

kitchen table.<br />

A deputation of pit brow<br />

women, taking with them their<br />

pit clothes, and accompanied <strong>by</strong> Mrs Park, the Lady<br />

Mayoress of Wigan, the Reverend Mitchell and Mrs<br />

Burrows, wife of the part owner of Atherton Collieries,<br />

went to London in May 1887 to lob<strong>by</strong> the Home<br />

Secretary.<br />

The parliamentary committee convened in 1866 to<br />

consider the work of women in the pits, took evidence<br />

from many sources, and found allegations of indecency<br />

and immorality unfounded and the clause was<br />

withdrawn.<br />

While pit work remained open to women, hostility<br />

remained, particularly from the Unions who did admit<br />

women as members.<br />

In 1911, women’s employment was again under threat.<br />

Miners were asking for a minimum wage,<br />

unemployment was high, women’s suffrage was on the<br />

agenda and an amendment to the proposed Mines Act<br />

threatened women with being excluded from work on<br />

the pit brow. Meetings were organised in Wigan where<br />

the Major, Sam Woods, and Stephen Walsh, the<br />

Labour MP for Ince, addressed the crowds in support<br />

of the women. Walsh asserted the women’s right to<br />

work at the pit head and denied they were degraded <strong>by</strong><br />

the work, but would have preferred them have more<br />

options for employment. The suffragette Annie<br />

Kenney of the Women’s Socialist and Political Union<br />

(WSPU) was sent to Wigan to help the pit<br />

brow women organise their opposition to the proposed<br />

legislation, and the organisation placed its campaigning<br />

expertise at their disposal. The WSPU objected to<br />

working-class women being denied the opportunity to<br />

work, rejecting the idea that conditions at the pit brow<br />

were any more harmful to women’s health than<br />

working in their own homes, and that the work was not<br />

physically beyond them.<br />

On Thursday the 8 th of August, the Lady Mayoress,<br />

Mrs Woods accompanied a delegation of forty-seven<br />

pit brow women from the Wigan area to London. The<br />

women created a stir as they headed towards the<br />

House of Commons dressed in their working clothes<br />

and clogs.<br />

More support came from local doctors who testified<br />

that the work was healthier than factory work. After<br />

much debate the amendment barring women from<br />

work at the pit head was withdrawn and women were<br />

free to continue.<br />

During the First World War, the number of women<br />

working the pit brow increased to about 11,300<br />

replacing men who went to fight. Women continued<br />

to work on the pit brow and in 1953, despite increased<br />

mechanisation, nearly 1,000 women worked for the<br />

National Coal Board. The last pit brow woman in<br />

Lancashire worked at Golborne Colliery until 1966,<br />

and the last ever worked in Whitehaven until 1972.<br />

Women Underground Again<br />

Women were not allowed to work underground in mines until the Employment Act of 1989 replaced<br />

sections of the Coal Mines Act 1842 and the Mines and Quarries Act of 1954 (which also prohibited this<br />

type of work for women).<br />

150 years after their ban, women were once again allowed to work underground.<br />

14 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

Truck and The Miners -<br />

The Truck Act 1831<br />

Truck was the practice of paying employees in goods<br />

rather than money, or compelling them to spend their<br />

wages at a store the employer either owned or was<br />

interested in financially and many miners were paid in<br />

this way. Although payment in kind continued well<br />

into the twentieth century, <strong>by</strong> the 1890s workers had<br />

become more concerned about other practices that<br />

prevented them from receiving the full value of their<br />

wages. These included employers taking heavy<br />

deductions from wages for disciplinary fines, for<br />

damaged work, for the rental of tools and materials,<br />

and for providing heat, light or standing room in the<br />

workplace.<br />

During the nineteenth century laws were passed to<br />

regulate these methods of cheating workers out of the<br />

full value of their earnings. The 1831 Truck Act made<br />

it illegal to pay certain artificers in anything but the<br />

current coin of the realm. The Act allowed workers in<br />

specifically listed trades to bring an action before two<br />

magistrates, who could award the worker the full<br />

monetary value of any wages paid in truck, and fine<br />

the offending employer. The 1887 Truck<br />

Amendment Act expanded these protections to nearly<br />

all manual workers, including those in Ireland, and<br />

entrusted their enforcement to the inspectors of mines<br />

and factories.<br />

The 1896 Truck Act was promoted <strong>by</strong> a Conservative<br />

government as offering protections to workers against<br />

arbitrary fines and deductions from wages, but<br />

sceptical trade-union leaders believed its primary<br />

purpose was to give employers a clear statutory right to<br />

take deductions. Section one of that Act applied to<br />

manual workers and shop assistants and enacted that<br />

disciplinary fines were only legal if they were<br />

authorised in a signed contract or a posted notice.<br />

The document had to list the specific acts or omissions<br />

for which a person could be fined, and the amounts<br />

that would be taken for each offence. Fines were only<br />

allowed for acts or omissions that harmed the business<br />

and had to be ‘fair and reasonable’. The remainder of<br />

the Act applied only to manual workers. It regulated<br />

deductions for damaged or spoiled work, stipulating<br />

that they also had to be part of a contract or posted<br />

notice, could not exceed the estimated loss to the<br />

employer, and had to be ‘fair and reasonable having<br />

regard to all circumstances of the case’. It also<br />

required deductions for materials and services<br />

provided <strong>by</strong> the employer to be part of a contract,<br />

and could not exceed the true cost, and had to be fair<br />

and reasonable.<br />

One objective of the 1831 Truck Act was to stop<br />

employers paying workers with cheques redeemable at<br />

distant banks or their own company stores located<br />

near the workplace. This was a barely disguised form<br />

of payment in kind (which the 1831 Act sought to<br />

outlaw), since the only place it was practicable for the<br />

employee to use the cheque was the company store.<br />

To prevent this, the Act allowed an employer to pay<br />

wages <strong>by</strong> cheque with the employee’s consent if it was<br />

drawn on a real bank ‘duly licensed to issue bank<br />

notes’ and located within fifteen miles of the place of<br />

payment.<br />

Cheques were ‘an instrument of torture’ for those who<br />

had no bank accounts, and often lived great distances<br />

from banks. If the cheque was delayed, the man’s wife<br />

could not shop unless she secured credit from the local<br />

shopkeeper. If the cheque arrived on Saturday<br />

morning, the husband would still be at work, and the<br />

wife could not cash it without his endorsement. She<br />

would have to travel to his work site or wait until his<br />

shift ended: ‘the cheque system makes the harassed<br />

housewife’s task of balancing her slender budget an<br />

impossible one’. This was especially so during<br />

wartime, with shortages of goods, when those with<br />

ready cash had first access to them.<br />

The inconvenient location of banks meant having<br />

cheques cashed <strong>by</strong> a publican, which wives wanted to<br />

avoid because of money lost on drink. Another option<br />

was a local shopkeeper, who would expect patronage<br />

for this service, and the shopkeeper would ‘know his<br />

earnings’.<br />

For most of the twentieth century, the majority of<br />

manual workers in England and Wales received their<br />

wages in cash – notes and coins – every week. As late<br />

as 1979, 77% of all manual workers still received cash<br />

wages weekly. In 1969, even 52% of non-manual<br />

workers still received cash wages; of manual workers<br />

only 5% were paid <strong>by</strong> cheque and 6% <strong>by</strong> bank transfer.<br />

Manual workers, individually and through their unions,<br />

repeatedly expressed a desire to be paid their wages in<br />

cash weekly.<br />

Over the years, the 1831 Truck Act has had a huge<br />

impact on and has heavily influenced workers’ rights.<br />

From the mid-1950s until the early 1960s, there was an<br />

ongoing tussle between British employers and the<br />

Trades Union Congress (TUC) over whether to repeal<br />

the 1831-96 Truck Acts which established the right of<br />

manual workers to be paid in cash (‘coin of the<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 15

Truck and The Miners (CONT.)<br />

realm’) and regulated employers’ ability to fine them<br />

or take deductions from their wages. Many<br />

employers advocated repeal, insisting that Truck<br />

legislation was not suited to the modern economy,<br />

interfered with freedom to contract and impeded<br />

more efficient forms of paying wages. Organised<br />

labour, through the TUC, argued that these laws<br />

protected workers from arbitrary deductions and<br />

prevented employers from imposing unpopular<br />

methods of paying wages (such as <strong>by</strong> cheque or bank<br />

transfer).<br />

Conclusion: from union voice<br />

to union exclusion<br />

The 1960 Payment of Wages Act operated for a<br />

quarter of a century. The passage of this law illuminates<br />

how organised labour gave working men and women<br />

some voice in their workplaces and government.<br />

Employers wanting new methods of paying wages<br />

would have to win workers’ consent, and sometimes<br />

this required concessions and incentives.<br />

By contrast, the 1986 Wages Act – which repealed<br />

all truck legislation and the 1960 Payment of Wages<br />

Act – was passed over the strenuous objections of<br />

organised labour and those bodies that provided legal<br />

advice to the poor.’ It made it much easier for<br />

employers to impose, as conditions of employment,<br />

methods of paying wages and the terms for deductions<br />

from wages (which no longer had to be ‘fair and<br />

reasonable’).<br />

The 1986 Act was part of an onslaught to make it<br />

easier for employers to resist union demands and<br />

recast the employment relationship as more individual<br />

and less collective. In 1960 a Conservative government<br />

had considered it necessary to consult and consider<br />

(and, in this case, be persuaded <strong>by</strong>) the views of<br />

workers, as represented <strong>by</strong> trade unions. By the 1980s<br />

it was explicit government policy to reduce the political<br />

power of trade unions and greatly limit their influence<br />

in the formation of public policy.<br />

Many UK workers now accept cashless pay as a fact of<br />

life. Although some struggle with access to banking<br />

services (as banks and cash machines are shut down or<br />

charge fees), many find cashless pay convenient. In<br />

1960, manual workers had many reasons to object to<br />

cashless pay or any dilution of the Truck Acts.<br />

Because of the trade-union organisation, and<br />

recognition <strong>by</strong> the Government of its legitimacy,<br />

workers then had a voice in possible changes to how<br />

they were paid. For example, before imposing<br />

cashless pay, employers, the state and banks would<br />

have to address concerns about the accessibility of<br />

banking.<br />

During the debates over the 1960 Payment of Wages<br />

Act, workers (through the TUC) were able to<br />

determine some of the rules under which they worked<br />

and lived.<br />

That was much less the case in 1986, and even less so<br />

today.<br />

The many collieries in Killamarsh<br />

Coal has been mined in Killamarsh since the 15 th<br />

century.<br />

Killamarsh has a long history as a mining village and<br />

there were many small mines in the 1800s.<br />

The first major mining operation opened at Norwood<br />

resulting in the population of Killamarsh almost<br />

doubling between 1861 and 1871.<br />

Westthorpe and High Moor pits followed and were the<br />

last two remaining, but are now gone, casualties of the<br />

early 1980s pit closure programme.<br />

Here are some of the smaller mines with names you<br />

may recognise.<br />

Comberwood Colliery Soft coal belonging to ESC<br />

Pole Esq was worked <strong>by</strong> Jonathan Batty and Co. From<br />

1853 to 1861.<br />

Messrs Webster took over the lease from March 1861<br />

to February 1865. Two shafts were sunk in 1852 and<br />

later a pumping pit added.<br />

The Many Pits<br />

in Killamarsh<br />

California • Water Wheel • Norwood<br />

Killamarsh Meadows • Netherthorpe<br />

Nether Moor • Sheepcote Hill • Old Delph<br />

Upperthorpe • Westthorpe • Ashley<br />

Dale • Webster’s • Killamarsh (Turner Ward)<br />

‘Perseverance Colliery’<br />

Mallender’s • Tuke’s<br />

Norburn’s Engine<br />

Hall’s Upperthorpe<br />

Westthorpe • Newland<br />

Bagley • High Moor<br />

16 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

The Davy Lamp<br />

Safet has always been an issue for mining om its early days to more recent<br />

mining accidents and catastophes.<br />

The humble miner’s safety lamp is, arguably, one of<br />

the most important inventions of the 1800s. The<br />

industrial revolution saw coal overtake wood as the<br />

most important fuel source for new industries and<br />

cities, with an ever increasing demand driving<br />

production and placing pressure on safe and efficient<br />

extraction. A lamp that could light the way, without<br />

causing a disastrous explosion was as essential a piece<br />

of miner’s equipment as a pick-axe.<br />

As the industrial revolution began to gather pace in the<br />

early 1800s, the demand for coal to fuel steam<br />

powered machines, trains and ships grew at a rapid<br />

rate. Coal mines opened across Britain particularly in<br />

Central and Northern England, South Wales and<br />

Scotland.<br />

<strong>Mining</strong> was<br />

exhausting, dirty<br />

and dangerous<br />

work. One of the<br />

biggest hazards was<br />

‘firedamp’ – the<br />

name given to the<br />

explosive gases that<br />

lay in between the<br />

layers of coal. In<br />

the early 1800s,<br />

miners used candles<br />

to light their way.<br />

Unsurprisingly, explosions<br />

were all too common, as<br />

the gases were released<br />

and ignited <strong>by</strong> the naked flames. Something needed to<br />

be done.<br />

One of the biggest advances to mining safety was the<br />

invention in 1815 of the safety lamp <strong>by</strong> Sir Humphry<br />

Davy, which became known as the ‘Davy lamp’.<br />

The lamp helped to prevent explosions caused <strong>by</strong> the<br />

presence of methane in the pits. Methane was also<br />

known as ‘firedamp’ and ‘minedamp’. The holes in<br />

the screen around the flame did not allow the fire to<br />

ignite the methane around the lamp. The flames of<br />

the lamp helped to notify miners of the invisible<br />

presence of flammable gases <strong>by</strong> burning brighter and<br />

with a blue tinge when flammable gases were present.<br />

Regulations were put in place that required all miners<br />

to use the new safety lamps. If they did not, and risked<br />

the safety of everyone in the colliery, they could be<br />

fined or imprisoned. Also, a miner could be<br />

disciplined for failing to operate his lamp safely.<br />

The safety lamp continued to evolve until the electric<br />

cap lamp began to take over in the 1900s.<br />

A Miner’s Snap<br />

When going on their shiſt Weshore miners would take their snap tin with them.<br />

Snap is a word that originally came from mining,<br />

and is a Yorkshire dialect word meaning food, and<br />

a snap tin is a metal container made the same<br />

shape as a slice of bread. It is thought that the<br />

sound of the tin snapping open and shut led to the<br />

food itself being referred to as snap.<br />

The snap tin was used <strong>by</strong> a miner to carry his<br />

lunch to keep him going during a long shift and<br />

usually contained bread and jam or bread and<br />

dripping. Other types of food were either too<br />

expensive or went off quickly in the hot conditions<br />

underground. Coal dust made the<br />

miners fingers dirty so dirty bread crusts were<br />

usually discarded.<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 17

The Underground Front -<br />

Remembering The Bevin Boys<br />

The stor of the Bevin Boys has been largely untold; the many men who spent their<br />

war on the so-called ‘undergound ont’ went unrecogised for almost half a centr.<br />

The story of the Bevin Boys has been largely untold;<br />

the many men who spent their war on the so-called<br />

‘underground front’ went unrecognised for almost half<br />

a century.<br />

At the start of World War II, the UK was highly<br />

dependent on coal, not only to power ships and trains,<br />

but as the main source of energy for electricity<br />

generation. Although output from mines had increased<br />

as the world economy recovered from the Great<br />

Depression, it was in decline again <strong>by</strong> the time war<br />

broke out in September 1939.<br />

At the beginning of the war, despite mining being a<br />

reserved occupation which exempted those working in<br />

it from military service, this only applied to men aged<br />

30 and over. Many men took advantage of this and<br />

went on to work in other reserved occupations that had<br />

better pay and working conditions, such as munitions<br />

factories.<br />

The Government, underestimating the value of strong<br />

younger coal miners conscripted them into the armed<br />

forces. By mid-1943 the coal mines had lost 36,000<br />

workers and they were generally not replaced because<br />

other likely young men were also being conscripted to<br />

the armed forces or transferred to higher paid war<br />

industries.<br />

Attempts were made to bring them back to mining,<br />

offering a better minimum wage. However, this only<br />

brought back around 500 men, which was not enough<br />

to solve the problem.<br />

Industrial relations were also poor. In the first half of<br />

1942, there were several local strikes over wages across<br />

the county, which also reduced output. In response,<br />

the Government increased the minimum weekly pay to<br />

83 shillings for those over the age of 21 working<br />

underground and established a new Ministry of Fuel,<br />

Light and Power, under the leadership of Gwilym<br />

Lloyd George, to oversee the reorganisation of coal<br />

production for the war effort. In late summer, a bonus<br />

scheme was proposed to reward workers in mines that<br />

exceeded their output targets. These measures<br />

resulted in an increase in production in the second half<br />

of 1942, although volumes were still short of the<br />

tonnage required.<br />

Absenteeism with miners taking time off work as a<br />

result of sickness for example, also rose through the<br />

war from 9.65% in December 1941 to 10.79% and<br />

14.40% in the Decembers of 1942 and 1943<br />

respectively.<br />

By October 1943, Britain was becoming desperate for<br />

a continued supply of coal, both for the industrial war<br />

effort and for keeping homes warm throughout the<br />

winter.<br />

Appeal for volunteers<br />

On 23 June 1941, Ernest Bevin made a broadcast<br />

appeal to former miners, asking them to volunteer to<br />

return to the pits, with an aim of increasing numbers of<br />

mineworkers <strong>by</strong> 50,000. He also issued a ‘standstill’<br />

order, to prevent more miners being called up to serve<br />

in the armed forces.<br />

On 12 th November 1943, Bevin made a radio<br />

broadcast aimed at sixth-form boys, to encourage<br />

them to work in the mines when they registered for<br />

National Service. He promised the students that, like<br />

those serving in the armed forces, they would be<br />

eligible for the Government’s further education<br />

scheme.<br />

“We need 720,000 men continuously<br />

employed in this industry. This is<br />

where you boys come in. Each one of<br />

you, I am sure, is full of enthusiasm<br />

to win this war. You are looking<br />

forward to the day when you can<br />

play your part with your friends and<br />

brothers who are in the Navy, the<br />

Army, the Air Force …<br />

But believe me, our fighting men will<br />

not be able to achieve their purpose<br />

unless we get an adequate supply<br />

of coal ….<br />

So when you go to register and the<br />

question is put to you “Will you go<br />

into the mines?” let your answer be,<br />

“Yes, I will go anywhere<br />

to help win this war”.<br />

Ernest Bevin 12 November 1943<br />

18 The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I

Conscription<br />

In 1943, four years into World War II the British<br />

government faced a terrible predicament – it was<br />

estimated that there were only three weeks of vital coal<br />

supply left.<br />

With an urgent need for more coal to fuel the war<br />

effort, and unable to attract enough workers to meet this<br />

demand, a large workforce of men was conscripted to<br />

work in the coal mines. Young British men were<br />

conscripted to work in coal mines between<br />

December 1943 and March 1948 to increase the rate<br />

of coal production, which had declined through the<br />

early years of World War II. The programme was<br />

named after Ernest Bevin, the Labour<br />

Party politician who was Minister of Labour and<br />

National Service in the wartime coalition government.<br />

They became known as the Bevin Boys.<br />

On 12 October 1943 Gwilym Lloyd George, Minister<br />

of Fuel and Power, announced in the House of<br />

Commons that some conscripts would be directed to<br />

the mines.<br />

On 2 December 1943 Ernest Bevin explained the<br />

scheme in more detail in Parliament, announcing his<br />

intention to draft 30,000 men aged 18 to 25 <strong>by</strong> 30<br />

April 1944.<br />

The selection of conscripts<br />

In 1943, Ernest Bevin, drew up plans to create a<br />

conscription scheme to send young men, between the<br />

ages of 18 and 25, down the mines. The men who<br />

were chosen had their National Service number drawn<br />

out of a hat and if it matched the last four digits of their<br />

number, they were sent to work in the mines rather<br />

than serve in the armed forces. To make the process<br />

random, from 14 December 1943 every month for 20<br />

months, one of Bevin’s secretaries drew numbers from<br />

his distinctive Homburg hat. If the number drawn<br />

matched the last digit of a man’s National Service<br />

number, he was directed to work in the mines. This<br />

was with the exception of any selected for highly skilled<br />

war work such as flying planes and in submarines, and<br />

men found physically unfit for mining.<br />

When boys were nearly 18 years old they received an<br />

official notification instructing them to report to a<br />

training centre in five days’ time. They were not<br />

allowed to say ‘No’. The arrival of the envelope<br />

explaining that their ‘number had come up’ changed<br />

the expectations and lives of many young men who<br />

were preparing to join the Services.<br />

This meant that many of the men chosen were not<br />

from areas that had coal mines or probably even knew<br />

what one was. Chosen <strong>by</strong> lot as ten per cent of all male<br />

conscripts, plus some volunteering as an alternative to<br />

military conscription, nearly 48,000 Bevin Boys<br />

performed vital and dangerous civil<br />

conscription service in coal mines.<br />

Conscripted miners came from many different trades<br />

and professions, from desk work to heavy manual<br />

labour, and included some who might otherwise have<br />

become commissioned officers.<br />

It wasn’t a popular choice for conscripts as 1 in 4 of<br />

those called up appealed the decision and some of<br />

those who still refused were sent to prison for their<br />

protest. Those who were sent to prison didn’t win as<br />

they were still sent to the mines after the end of their<br />

prison sentence. Even though there was defiance<br />

against it, there were also many who chose to work in<br />

the mines on their call up forms.<br />

An appeals process was set up, to allow conscripts the<br />

opportunity to challenge the decision to send them to<br />

the pits, although decisions were rarely overturned. By<br />

31st May 1944, 285 conscripts had refused to serve as<br />

miners, of whom 135 had been prosecuted and 32 had<br />

been given a prison sentence.<br />

However, this caused a lot of upset, as many young<br />

men wanted to join the fighting forces and felt that as<br />

miners they would not be valued.<br />

Training<br />

Whatever way men were called up, they would have<br />

had to pass a medical examination before they could<br />

go on to do their training.<br />

Around 2,300 of them were sent to the Der<strong>by</strong>shire and<br />

Nottinghamshire coalfields. Two such training centres<br />

were at Ollerton Colliery in Nottinghamshire and<br />

Creswell Colliery in Der<strong>by</strong>shire.<br />

Bevin Boys with no previous experience of mining<br />

were given six weeks' training (four in a classroom-type<br />

setting and two at their assigned colliery). For their<br />

first four weeks of underground work, they were<br />

supervised <strong>by</strong> an experienced miner. With the<br />

exception of those working in the South Wales<br />

coalfields, the conscripts could not work at the coalface<br />

until they had accrued four months' experience<br />

underground. When compared with the seasoned<br />

miners already working in the mines, many of whom<br />

had been there since they were young teenagers<br />

themselves, the Bevin Boys were viewed with suspicion<br />

for their lack of experience.<br />

For the most part, the Bevin Boys were not directly<br />

involved in cutting coal from the mine face, but acted<br />

The <strong>History</strong> of <strong>Mining</strong> - Chapter I 19

Remembering The Bevin Boys (CONT.)<br />

instead as colliers’ assistants, responsible for filling tubs<br />

or wagons and hauling them back to the shaft for<br />

transport to the surface. Conscripts were supplied with<br />

helmets and steel-capped safety boots. After training<br />

was over, they were sent to a colliery in the same<br />

district as their training had taken place. This would<br />

have been anywhere that they were needed. For many<br />

it meant their first experience of the real working<br />

conditions miners dealt with. It was a harsh life, and<br />

many didn’t attend their shifts regularly. It would also<br />