InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 6

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

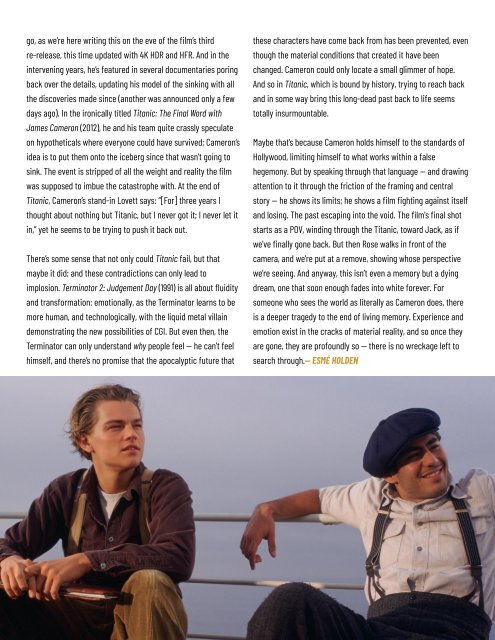

go, as we’re here writing this on the eve of the film’s third<br />

re-release, this time updated with 4K HDR and HFR. And in the<br />

intervening years, he’s featured in several documentaries poring<br />

back over the details, updating his model of the sinking with all<br />

the discoveries made since (another was announced only a few<br />

days ago). In the ironically titled Titanic: The Final Word with<br />

James Cameron (2012), he and his team quite crassly speculate<br />

on hypotheticals where everyone could have survived; Cameron’s<br />

idea is to put them onto the iceberg since that wasn’t going to<br />

sink. The event is stripped of all the weight and reality the film<br />

was supposed to imbue the catastrophe with. At the end of<br />

Titanic, Cameron’s stand-in Lovett says: “[For] three years I<br />

thought about nothing but Titanic, but I never got it; I never let it<br />

in,” yet he seems to be trying to push it back out.<br />

There’s some sense that not only could Titanic fail, but that<br />

maybe it did; and these contradictions can only lead to<br />

implosion. Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) is all about fluidity<br />

and transformation: emotionally, as the Terminator learns to be<br />

more human, and technologically, with the liquid metal villain<br />

demonstrating the new possibilities of CGI. But even then, the<br />

Terminator can only understand why people feel <strong>—</strong> he can’t feel<br />

himself, and there’s no promise that the apocalyptic future that<br />

these characters have come back from has been prevented, even<br />

though the material conditions that created it have been<br />

changed. Cameron could only locate a small glimmer of hope.<br />

And so in Titanic, which is bound by history, trying to reach back<br />

and in some way bring this long-dead past back to life seems<br />

totally insurmountable.<br />

Maybe that’s because Cameron holds himself to the standards of<br />

Hollywood, limiting himself to what works within a false<br />

hegemony. But by speaking through that language <strong>—</strong> and drawing<br />

attention to it through the friction of the framing and central<br />

story <strong>—</strong> he shows its limits; he shows a film fighting against itself<br />

and losing. The past escaping into the void. The film's final shot<br />

starts as a POV, winding through the Titanic, toward Jack, as if<br />

we’ve finally gone back. But then Rose walks in front of the<br />

camera, and we’re put at a remove, showing whose perspective<br />

we’re seeing. And anyway, this isn’t even a memory but a dying<br />

dream, one that soon enough fades into white forever. For<br />

someone who sees the world as literally as Cameron does, there<br />

is a deeper tragedy to the end of living memory. Experience and<br />

emotion exist in the cracks of material reality, and so once they<br />

are gone, they are profoundly so <strong>—</strong> there is no wreckage left to<br />

search through.<strong>—</strong> ESMÉ HOLDEN