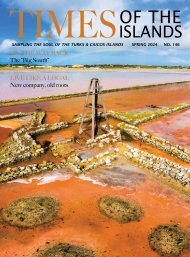

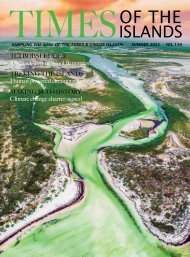

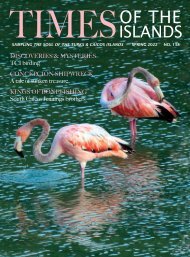

Times of the Islands Winter 2023/24

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, real estate, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Presents the "soul of the Turks & Caicos Islands" with in-depth features about local people, culture, history, environment, real estate, businesses, resorts, restaurants and activities.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

green pages newsletter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> department <strong>of</strong> environment & coastal resources<br />

body and a hard outer shell. However, over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir evolution, cephalopods lost this protective covering<br />

in favor <strong>of</strong> more sophisticated “squishy” defenses, such as<br />

crypsis, enhanced predator detection abilities (sight and<br />

“smell”), and a complex nervous system. Cephalopods<br />

do not have <strong>the</strong> rigid system <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r internal or external<br />

hard structures (bones or exoskeletons) that we and<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>r animals use to get around. In human bodies,<br />

our bones work toge<strong>the</strong>r with our cartilage, muscles,<br />

ligaments, and tendons to produce movement. The muscles<br />

are attached to <strong>the</strong> rigid skeleton which provides<br />

anchor points and support against which muscles can<br />

push and pull. Octopods, by contrast, lack this support,<br />

and instead utilize <strong>the</strong> pressure created by <strong>the</strong> fluid-filled<br />

tissues inside <strong>the</strong>ir bodies to provide support for limb<br />

movement.<br />

Instead <strong>of</strong> bones or an exoskeleton, octopods are<br />

composed almost entirely <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t muscle and tissue. The<br />

muscles <strong>of</strong> octopod arms are organized into two groups<br />

which perform opposing but complementary actions to<br />

produce movement: While one group <strong>of</strong> muscles contracts<br />

to provide force, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r group relaxes, causing it<br />

to elongate and stretch, thus causing limb extension. The<br />

general lack <strong>of</strong> hard parts in <strong>the</strong>ir bodies allows octopods<br />

a wider range <strong>of</strong> motion than o<strong>the</strong>r species, since <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are not limited by <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> motion <strong>of</strong> a joint, but can<br />

bend a limb almost anywhere along its length. Moreover,<br />

<strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> hard parts in <strong>the</strong> octopod body (except <strong>the</strong><br />

beak) gives <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> ability to squeeze through any gap<br />

or hole in <strong>the</strong> substrate that is wider than that beak.<br />

So, if <strong>the</strong>y don’t have any rigid structures, how do<br />

octopods use <strong>the</strong>ir limbs to walk or run? Ra<strong>the</strong>r than utilizing<br />

bendable limbs with a joint like vertebrates and<br />

arthropods do, octopods use ei<strong>the</strong>r a smooth continuous<br />

rolling motion along <strong>the</strong> length <strong>of</strong> two arms, or alternate<br />

between a stiffened LIV and RIV. In <strong>the</strong> algae octopus,<br />

coconut octopus, and sand octopus, bipedal locomotion<br />

is achieved by <strong>the</strong> octopod rolling backwards along <strong>the</strong><br />

rearmost pair <strong>of</strong> arms (IV), while <strong>the</strong> common octopus<br />

“hops” backwards on two arms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same side, such as<br />

RIII and RIV or LII and LIII.<br />

Stepping into <strong>the</strong> light:<br />

Discovering bipedalism in o<strong>the</strong>r octopods<br />

Bipedal locomotion has now been documented in four<br />

genera <strong>of</strong> octopods living in three ecologically-distinct<br />

regions: <strong>the</strong> Indo Pacific, <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean, and <strong>the</strong><br />

tropical western Atlantic. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se was discovered<br />

recently by students and scientists at <strong>the</strong> School for Field<br />

Studies Center for Marine Resource Studies (CMRS) on<br />

South Caicos in <strong>the</strong> Turks & Caicos <strong>Islands</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Fall <strong>of</strong><br />

2021.<br />

The research team (nicknamed “NoctoSquad”)<br />

“stumbled” upon this fascinating behavior while filming<br />

Callistoctopus furvus for a directed research project on<br />

octopus foraging and skin patterning. In <strong>the</strong>se video<br />

sequences, three C. furvus can be seen “walking” bipedally<br />

using mainly arms LIV and RIV on fifteen separate<br />

occasions from anywhere between one and a dozen steps.<br />

While doing so, <strong>the</strong> octopuses turn brown and engage in<br />

<strong>the</strong> flamboyant display, causing <strong>the</strong>m to resemble strands<br />

<strong>of</strong> brown algae floating nearby. Recognizing <strong>the</strong> importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first sightings <strong>of</strong> this behavior in this genus<br />

and species <strong>of</strong> octopus, faculty and staff <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CMRS<br />

published <strong>the</strong>ir observations in <strong>the</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Molluscan<br />

Studies. Their observations were also notable in that <strong>the</strong><br />

individuals that engaged in this behavior were distinctly<br />

larger than was thought possible for bipedalism to occur<br />

in octopuses.<br />

Bipedalism is likely even more widespread among<br />

octopods than currently recognized. More observations<br />

<strong>of</strong> octopod behavior in <strong>the</strong> wild are needed, especially as<br />

new species <strong>of</strong> octopods are discovered or reclassified<br />

every year. (Currently <strong>the</strong>re are around 300 species.)<br />

Formal research is critical to this effort, but so too is<br />

“community-” or “citizen-” science. Anyone living in proximity<br />

to an ocean can grab <strong>the</strong>ir mask, fins, and camera<br />

and non-invasively (no touching!) document cephalopods<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r marine animals in <strong>the</strong>ir native habitats, no credentials<br />

needed. So, get out <strong>the</strong>re and explore! a<br />

This article was originally published on OctoNation.<br />

com, https://octonation.com/bipedal-locomo-<br />

tion-two-legged-walking-in-octopods/?fbclid=IwAR2L-<br />

Hjf5Sf9tsHy5p_9HI04-zZlTFvvcsbN-2-XZbzgtGKfTFY-<br />

9JrEGHwFc.<br />

For detailed article references or more information<br />

about The School for Field Studies, contact Director Heidi<br />

Hertler on South Caicos at hhertler@fieldstudies.org or<br />

visit www.fieldstudies.org.<br />

36 www.timespub.tc