European Journal of Scientific Research - EuroJournals

European Journal of Scientific Research - EuroJournals

European Journal of Scientific Research - EuroJournals

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

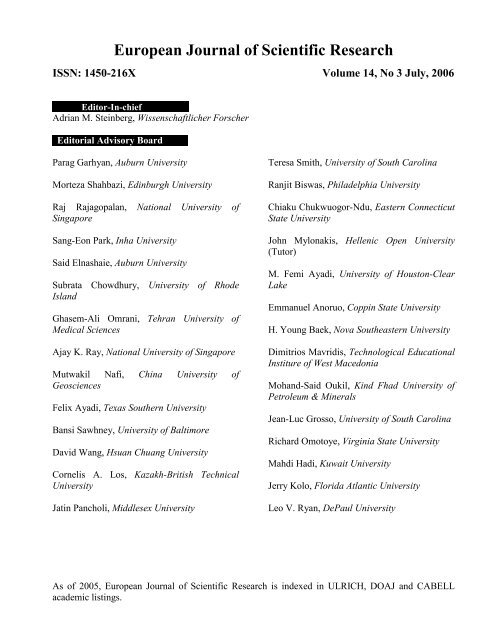

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

ISSN: 1450-216X Volume 14, No 3 July, 2006<br />

Editor-In-chief or e<br />

Adrian M. Steinberg, Wissenschaftlicher Forscher<br />

Editorial Advisory Board e<br />

Parag Garhyan, Auburn University<br />

Morteza Shahbazi, Edinburgh University<br />

Raj Rajagopalan, National University <strong>of</strong><br />

Singapore<br />

Sang-Eon Park, Inha University<br />

Said Elnashaie, Auburn University<br />

Subrata Chowdhury, University <strong>of</strong> Rhode<br />

Island<br />

Ghasem-Ali Omrani, Tehran University <strong>of</strong><br />

Medical Sciences<br />

Ajay K. Ray, National University <strong>of</strong> Singapore<br />

Mutwakil Nafi, China University <strong>of</strong><br />

Geosciences<br />

Felix Ayadi, Texas Southern University<br />

Bansi Sawhney, University <strong>of</strong> Baltimore<br />

David Wang, Hsuan Chuang University<br />

Cornelis A. Los, Kazakh-British Technical<br />

University<br />

Jatin Pancholi, Middlesex University<br />

Teresa Smith, University <strong>of</strong> South Carolina<br />

Ranjit Biswas, Philadelphia University<br />

Chiaku Chukwuogor-Ndu, Eastern Connecticut<br />

State University<br />

John Mylonakis, Hellenic Open University<br />

(Tutor)<br />

M. Femi Ayadi, University <strong>of</strong> Houston-Clear<br />

Lake<br />

Emmanuel Anoruo, Coppin State University<br />

H. Young Baek, Nova Southeastern University<br />

Dimitrios Mavridis, Technological Educational<br />

Institure <strong>of</strong> West Macedonia<br />

Mohand-Said Oukil, Kind Fhad University <strong>of</strong><br />

Petroleum & Minerals<br />

Jean-Luc Grosso, University <strong>of</strong> South Carolina<br />

Richard Omotoye, Virginia State University<br />

Mahdi Hadi, Kuwait University<br />

Jerry Kolo, Florida Atlantic University<br />

Leo V. Ryan, DePaul University<br />

As <strong>of</strong> 2005, <strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong> is indexed in ULRICH, DOAJ and CABELL<br />

academic listings.

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm<br />

Editorial Policies:<br />

1) <strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong> is an international <strong>of</strong>ficial journal publishing high quality<br />

research papers, reviews, and short communications in the fields <strong>of</strong> biology, chemistry, physics,<br />

environmental sciences, mathematics, geology, engineering, computer science, social sciences,<br />

medicine, industrial, and all other applied and theoretical sciences. The journal welcomes submission<br />

<strong>of</strong> articles through ejsr@eurojournals.com.<br />

2) The journal realizes the meaning <strong>of</strong> fast publication to researchers, particularly to those working in<br />

competitive & dynamic fields. Hence, it <strong>of</strong>fers an exceptionally fast publication schedule including<br />

prompt peer-review by the experts in the field and immediate publication upon acceptance. It is the<br />

major editorial policy to review the submitted articles as fast as possible and promptly include them in<br />

the forthcoming issues should they pass the evaluation process.<br />

3) All research and reviews published in the journal have been fully peer-reviewed by two, and in some<br />

cases, three internal or external reviewers. Unless they are out <strong>of</strong> scope for the journal, or are <strong>of</strong> an<br />

unacceptably low standard <strong>of</strong> presentation, submitted articles will be sent to peer reviewers. They will<br />

generally be reviewed by two experts with the aim <strong>of</strong> reaching a first decision within a three day<br />

period. Reviewers have to sign their reports and are asked to declare any competing interests. Any<br />

suggested external peer reviewers should not have published with any <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>of</strong> the manuscript<br />

within the past five years and should not be members <strong>of</strong> the same research institution. Suggested<br />

reviewers will be considered alongside potential reviewers identified by their publication record or<br />

recommended by Editorial Board members. Reviewers are asked whether the manuscript is<br />

scientifically sound and coherent, how interesting it is and whether the quality <strong>of</strong> the writing is<br />

acceptable. Where possible, the final decision is made on the basis that the peer reviewers are in<br />

accordance with one another, or that at least there is no strong dissenting view.<br />

4) In cases where there is strong disagreement either among peer reviewers or between the authors and<br />

peer reviewers, advice is sought from a member <strong>of</strong> the journal's Editorial Board. The journal allows a<br />

maximum <strong>of</strong> two revisions <strong>of</strong> any manuscripts. The ultimate responsibility for any decision lies with<br />

the Editor-in-Chief. Reviewers are also asked to indicate which articles they consider to be especially<br />

interesting or significant. These articles may be given greater prominence and greater external<br />

publicity.<br />

5) Any manuscript submitted to the journals must not already have been published in another journal or<br />

be under consideration by any other journal, although it may have been deposited on a preprint server.<br />

Manuscripts that are derived from papers presented at conferences can be submitted even if they have<br />

been published as part <strong>of</strong> the conference proceedings in a peer reviewed journal. Authors are required<br />

to ensure that no material submitted as part <strong>of</strong> a manuscript infringes existing copyrights, or the rights<br />

<strong>of</strong> a third party. Contributing authors retain copyright to their work.<br />

6) Submission <strong>of</strong> a manuscript to Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s, Inc. implies that all authors have read and agreed to its<br />

content, and that any experimental research that is reported in the manuscript has been performed with<br />

the approval <strong>of</strong> an appropriate ethics committee. <strong>Research</strong> carried out on humans must be in<br />

compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, and any experimental research on animals should follow<br />

internationally recognized guidelines. A statement to this effect must appear in the Methods section <strong>of</strong><br />

the manuscript, including the name <strong>of</strong> the body which gave approval, with a reference number where

appropriate. Manuscripts may be rejected if the editorial <strong>of</strong>fice considers that the research has not been<br />

carried out within an ethical framework, e.g. if the severity <strong>of</strong> the experimental procedure is not<br />

justified by the value <strong>of</strong> the knowledge gained. Generic drug names should generally be used where<br />

appropriate. When proprietary brands are used in research, include the brand names in parentheses in<br />

the Methods section.<br />

7) Manuscripts must be submitted by one <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>of</strong> the manuscript, and should not be submitted<br />

by anyone on their behalf. The submitting author takes responsibility for the article during submission<br />

and peer review. To facilitate rapid publication and to minimize administrative costs, the journal<br />

accepts only online submissions through ejsr@eurojournals.com. E-mails should clearly state the name<br />

<strong>of</strong> the article as well as full names and e-mail addresses <strong>of</strong> all the contributing authors.<br />

8) The journal makes all published original research immediately accessible through<br />

www.Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s.com without subscription charges or registration barriers. <strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong> indexed in ULRICH, DOAJ and CABELL academic listings. Through its open<br />

access policy, the <strong>Journal</strong> is committed permanently to maintaining this policy. All research published<br />

in the. <strong>Journal</strong> is fully peer reviewed. This process is streamlined thanks to a user-friendly, web-based<br />

system for submission and for referees to view manuscripts and return their reviews. The journal does<br />

not have page charges, color figure charges or submission fees. However, there is an article-processing<br />

and publication charge.<br />

Further information is available at: http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm<br />

© Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s Publishing, Inc. 2005

Contents<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

Volume 14, No 3 July 2006<br />

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from Scotland 311-318<br />

Odeyinka, S.M, Hector, B.L and Ørskov, E.R<br />

Determination <strong>of</strong> Sample Size 319-325<br />

Nadia Saeed, Muhammad Khalid Pervaiz and Muhammad Qaiser Shahbaz<br />

Model-Based Adaptive Chaos Control using Lyapunov Exponents 326-332<br />

Amin Yazdanpanah Goharrizi and Mehdi Semin<br />

Investigation <strong>of</strong> Complex Formation PDTC with Ni(II) in Physiological Conditions 333-338<br />

S. J. Fatemi , A. Badiei and A. Hooshmand<br />

Germination Studies in Selected Native Desert Plants <strong>of</strong> Kuwait 339-345<br />

Sameeha Zaman, Shyamala Padmesh, Narayan R. Bhat and Harby Tawfiq<br />

Age at Menarche, Current Premenstrual Syndrome and<br />

Health Risk Behaviour <strong>of</strong> Young People in Ibadan, Nigeria 346-353<br />

Moronkola, O.A and Aladesanyi, O.A<br />

The Assesment <strong>of</strong> Participation Decisionmaking <strong>of</strong> Head Nurses to<br />

According Training Programs and Supply Medical Equipment and<br />

Safty <strong>of</strong> Occupational Health and Alloceation Budget and Related<br />

between their Individual Variables at the Training Hospitals <strong>of</strong> Iran<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences 2005 354-358<br />

Maryam Nooritajer, Faezeh Nouroozinjad, Ezatjafarchla, Fatemeh and Hosseini<br />

Aetiology and Epidemiology <strong>of</strong> Sever Infantile Diarrhoea in Baghdad, Iraq 359-371<br />

E. N. Al-Kaissi, M. Makki and M. Al-Khoja<br />

Islam and Education from Religious Man’s Perspectives 372-387<br />

Nazenin Ruso<br />

Characterization <strong>of</strong> a Possible Modification <strong>of</strong> the Relation Rain-Flow in a<br />

Climatic Context <strong>of</strong> Variability: Case <strong>of</strong> the Catchment Area <strong>of</strong> the<br />

N’zi (Bandama) (Côte.D'ivoire) 388-400<br />

Amani Michel Kouassi, K<strong>of</strong>fi Fernand Kouame, Bi Tié Albert Goula,<br />

Jean-Emmanuel Paturel, Théophile Lasm and Jean Biemi<br />

Seedling Growth <strong>of</strong> Gmelina Arborea (Roxb) as Influenced by Crude Oil in Soil 401-406<br />

Agbogidi, O. M, Dolor, D. E and Okechukwu, E. M

A Comparative Analysis <strong>of</strong> Gibberellic Acid Content with Respect to<br />

Tuber Induction in Potato Plants Grown Under Differential Photoperiod<br />

and Temperature 407-416<br />

Ahmed Malkawi<br />

<strong>Research</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Characteristics <strong>of</strong> a Solar Panel Radiated with Со2 Laser, as<br />

Means for Injection on Fading Satellites 417-425<br />

M. Zamfirov<br />

Feature Selection Based on Statistical Analysis 426-433<br />

Nooritawati Md Tahir, Aini Hussain, Salina Abdul Samad,<br />

Hafizah Husain and Mohd Yus<strong>of</strong> Jamaluddin<br />

Sublingual Schwannoma in a Nigerian African-a Case Report 434-438<br />

Rahman G.A, Alabi.B.S, Afolabi.O.A, Bramoh.K.T and Buhari.M.O<br />

Health Impact Assessement <strong>of</strong> Multinational Corporations Oil Exploration in<br />

the Niger-Delta Region <strong>of</strong> Nigeria 439-446<br />

Ewhrudjakpor, Christian<br />

Development <strong>of</strong> Organic Carbon Sequestration Models for<br />

Dipterocarpus Turbinatus, Acacia Auriculiformis and Eucalyptus Camaldulensis<br />

and their Potentiality 447-455<br />

Md. Shahadat Hossain and Gouri Rani Banik

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

ISSN 1450-216X Vol.14 No.3 (2006), pp. 311-318<br />

© Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s Publishing, Inc. 2006<br />

http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm<br />

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from<br />

Scotland<br />

Odeyinka, S.M<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Animal Science, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Agriculture<br />

Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria<br />

Email:smodeyinka@yahoo.co.uk<br />

Hector, B.L<br />

The Macaulay Institute, Craigiebuckler<br />

Aberdeen AB15 8QH, UK<br />

Ørskov, E.R<br />

The Macaulay Institute, Craigiebuckler<br />

Aberdeen AB15 8QH, UK<br />

Abstract<br />

The nutritive value <strong>of</strong> twelve Scottish plants (trees, legumes and grasses): 1. Pinus<br />

sylvestris L., 2. Lolium perenne L., 3. Calluna vulgaris L., 4. Picea sitchensis (Bong.)<br />

Carr; 5. Chamaenerion angustifolium (L.) Scop., 6. Luzula sylvatica, 7. Pseudotsuga<br />

menziesii F. Mirb., 8. Fagus sylvatica L., 9. Vaccinum myrtillus L., 10. Brassica oleracea,<br />

11. Acer pseudoplatanus L., 12. Juncus effusus L. were determined using in vitro gas<br />

production, in sacco DM degradability and in vivo digestibility.<br />

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) was used in the gas production to determine presence <strong>of</strong><br />

phenolic related antinutritive factor. Species had significant effect on in vitro gas<br />

production (P

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from Scotland 312<br />

Introduction<br />

Nutrition is perhaps the most important consideration in livestock management. The nutritive value <strong>of</strong><br />

a feed is essentially a function <strong>of</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> its energy and nutrient contents. According to Van<br />

Soest (1983), nutritive value is multifaceted, but useful attributes <strong>of</strong> a feed are feed consumption and<br />

digestibility. Browse (shrubs and tree foliage) plays a significant role in providing fodder for ruminants<br />

in many parts <strong>of</strong> the world (Adugna et.al. 1997). Tree fodder is generally richer in protein and minerals<br />

and is used as a dry season supplement to poor quality natural pasture and or fibrous crop residues<br />

(Devendra, 1990; Kibbon and Orskov, 1993).<br />

In vitro methods for laboratory estimations and feed degradation are important tools for<br />

ruminant nutritionists. The Hohenheim in vitro gas test is extensively used for the estimation <strong>of</strong> in vivo<br />

digestibility and metabolizable energy for ruminants (Menke et al., 1979). Internationally, the gas test<br />

is <strong>of</strong> increasing interest because <strong>of</strong> the possibility <strong>of</strong> estimating the extent and rate <strong>of</strong> degradation in<br />

one sample by time series measurement <strong>of</strong> the accumulating gas volume (Blummel et al., 1990;<br />

Khazaal et al., 1993, Orskov, 2000). However, the presence <strong>of</strong> tannins and other phenolic compounds<br />

in a large number <strong>of</strong> nutritionally important shrubs and tree leave decrease their utilization as animal<br />

feed. In general, most browse species contain phenolic compounds that reduce digestibility and<br />

availability <strong>of</strong> protein, and contribute to unpalatability and reduced intake (Woodward and Reed, 1989;<br />

Kumar and Vaaithiyanaathan, 1990; Kibon and Ørskov, 1993). There have been several studies aimed<br />

at inactivating phenolic compounds using polyvinyl pyrolidone (PVP) or polyethylene glycol (PEG).<br />

Thus PEG has been used to adsorb plant phenolics during the extraction <strong>of</strong> enzymes because <strong>of</strong> its<br />

hydrophobic properties (Badran and Jones, 1965). A potential increase in in vitro (Kumar and<br />

Vaithiyanathan, 1990) and in vivo (Jones and Mangan, 1977) digestibility <strong>of</strong> tannin rich feeds by the<br />

addition <strong>of</strong> PEG-4000 has also been reported.<br />

While the nutritional potential and limitations <strong>of</strong> many tropical and Mediterranean browse<br />

species have been documented, comparatively little has been done on temperate trees species. Thus, the<br />

objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to assess the nutritive value <strong>of</strong> some tree species from Scotland based on<br />

their in vitro gas production, DM degradability in sacco and in vivo digestibility.<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

The forages used in the study were 1. Pinus sylvestris L. (Scots pine), 2. Lolium perenne L. (grass)<br />

/Trifolium repens L. (Clover) mixture, 3. Calluna vulgaris L. (Heather), 4. Picea sitchensis (Bong.)<br />

Carr. (Sitka spruce), 5. Chamaenerion angustifolium (L.) Scop. (Roseby willowherb), 6. Luzula<br />

sylvatica (Great Woodrush), 7. Pseudotsuga menziesii F. Mirb. (Douglas fir), 8. Fagus sylvatica L.<br />

(Beech), 9. Vaccinum myrtillus L. (Vaccinum), 10. Brassica oleracea (Cabbage), 11. Acer<br />

pseudoplatanus L. (Sycamore), 12. Juncus effusus L. (S<strong>of</strong>t Rush)<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the tree leaves and browse species were hand harvested at Macaulay <strong>Research</strong><br />

Institute's experimental station at Glensaugh, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. The L. perenne was machine<br />

harvested while the B. oleracea was purchased from a local farmer. The samples were oven dried at<br />

70ºC for 48 hours and milled using a 1-mm screen.<br />

In vitro gas production<br />

In vitro gas production was measured using the method described by Blummel and Orskov (1993) by<br />

incubating the forage samples with buffer and rumen fluid and recording the volume <strong>of</strong> gas produced<br />

over time. Measurements were made after 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours <strong>of</strong> incubation. Analysis was<br />

carried out in triplicate in the presence and absence <strong>of</strong> 200mg PEG, molecular weight 4000 (Sigma-<br />

Aldrich Company Ltd, Poole, Dorset, UK). The gas syringes were incubated by suspension from a rack<br />

fitted above a water bath. The rumen fluid was taken from two sheep, fitted with permanent rumen<br />

cannulae, receiving a diet <strong>of</strong> dried L. perenne pellets and hay.

313 Odeyinka, S.M, Hector, B.L and Ørskov, E.R<br />

Estimations <strong>of</strong> rumen degradability were made using the nylon bag technique described by<br />

Ørskov et al. (1980). The nylon bags used were 8cm x 14cm, 40 to 60-micron pore size (IFRU, The<br />

Macaulay Institute, Aberdeen, UK). Duplicate samples were incubated in 2 different sheep receiving<br />

the same diet as above. The following incubation times were used: 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours.<br />

The results <strong>of</strong> the experiments were analysed using “Fitcurve” macro (Chen, X.B., 1995. IFRU,<br />

The Macaulay Institute, Aberdeen, UK) for Micros<strong>of</strong>t Excel. The program is a utility for processing<br />

data <strong>of</strong> feed degradability or in vitro gas production, it fits the data to the exponential equation<br />

p=a+b(1-e -ct ) developed by Ørskov and McDonald (1979). For degradability characteristics, p is the<br />

percentage degraded at time t, a is the intercept <strong>of</strong> the line at time zero, b is the insoluble but<br />

degradable fraction, therefore a+b is the potential degradability and c is the rate <strong>of</strong> degradation. While<br />

this equation was originally developed for protein supplements in which the intercept was also an<br />

approximate expression <strong>of</strong> solubility, this is not the case for trees and shrubs due to the occurrence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

lag phase or a period in which there is no net disappearance <strong>of</strong> the insoluble but fermentable substrate<br />

(Ørskov and Ryle, 1990). Accordingly, A is solubility and small particle loss, B is the insoluble but<br />

fermentable fraction (B=(a+b)–A). For in vitro gas production, the data is fitted to the same equation, p<br />

is the volume <strong>of</strong> gas produced at time t, a is the intercept <strong>of</strong> the line at time zero, b is the potential gas<br />

production and c is the rate constant (Ørskov and Ryle, 1990).<br />

In vivo digestibility<br />

In this experiment, 12 mature sheep were used. Animals were housed in metabolism crates. Total 24hour<br />

urine and faeces collections were made throughout the experiment by means <strong>of</strong> chutes and<br />

separators fitted underneath the metabolism crates. The experiment consisted <strong>of</strong> individual<br />

experimental periods, separated by periods <strong>of</strong> 14 days. During each experimental period, animals were<br />

randomly allocated to different experimental treatments in a partial Latin square design.<br />

Animal 1 Animal 2 Animal 3 Animal 4 Animal 5 Animal 6<br />

Period 1 A B A+B+C D E D+E+F<br />

Period 2 B A+B B+C E D+E E+F<br />

Period 3 C C A+C F F D+F<br />

Period 4 A+B+C B+C A D+E+F E+F D<br />

Period 5 A+B A A+B D+E D D+E<br />

Period 6 B+C A+C B E+F D+F E<br />

Period 7 A+C A+B+C C F+D D+E+F F<br />

Animal 7 Animal 8 Animal 9 Animal 10 Animal 11 Animal 12<br />

Period 1 G H G+H+I J J J<br />

Period 2 H G+H H+I K K K<br />

Period 3 I I G+I L L L<br />

Period 4 G+H+I H+I G J+K+L J+K+L J+K+L<br />

Period 5 G+H G G+H J+K J+K J+K<br />

Period 6 H+I G+I H K+L K+L K+L<br />

Period 7 I+J G+H+I I L+J L+J L+J<br />

A letter (A, B, C, D, etc) represents an individual plant material.<br />

Statistical Analysis: The results were subjected to statistical analysis using GENSTAT 5<br />

Release 4.1 s<strong>of</strong>tware package. Analysis <strong>of</strong> variance was done to detect differences between treatments.<br />

Differences between treatments were analysed using means across replications. Least significant<br />

difference (LSD) test was used to compare treatment means

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from Scotland 314<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

Table 1 shows the in vitro gas production characteristics <strong>of</strong> the different Scottish forage species. As<br />

expected, gas production increased with the duration/length <strong>of</strong> incubation (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Species<br />

and PEG had significant effect on in vitro gas production (P L.<br />

perenne > F. sylvatica >A. pseudoplatanus > C. angustifolium > C. vulgaris J. effusus > P. sylvestris<br />

> L. sylvatica > P. menziesii > P. sitchensis >V. myrtillusi. There was no significant difference in gas<br />

production <strong>of</strong> L. perenne and A. pseudoplatanus and also P.sylvestris and J. effuses at the 96hr . There<br />

was significant increase in gas production with the addition <strong>of</strong> PEG (P

315 Odeyinka, S.M, Hector, B.L and Ørskov, E.R<br />

Gas Production (ml)<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Figure 1: In vitro gas production <strong>of</strong> the leaves <strong>of</strong> Scottish plant species<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100<br />

Hours<br />

Table 2: Effect <strong>of</strong> PEG on in vitro gas production <strong>of</strong> Scottish plants<br />

Fagus sylvatica<br />

Brassica oleraceae<br />

Pseudotsuga<br />

menziesii<br />

Lolium perenne<br />

Calluna vulgaris<br />

Chamaenerion<br />

angustifolium<br />

Luzula sylvatica<br />

Pinus sylvestris<br />

Picea sitchensis<br />

Acer pseudoplatanus<br />

Vaccinium myrtillus<br />

Juncus effusus<br />

Time, h<br />

Species s 3 6 12 24 48 72 96<br />

Fagus sylvatica 3.56 a 6.87 a 11.70 a 21.75 a 33.69 a 36.03 a 37.38 a<br />

Fagus sylvatica + PEG 4.86 b 9.75 b 15.58 b 26.30 b 33.90 a 40.12 b 42.86 b<br />

Brassica oleraceae 7.92 a 18.11 a 34.81 a 46.98 a 55.75 a 59.15 a 60.85 a<br />

Brassica oleraceae + PEG 7.93 a 19.09 b 36.71 b 49.05 b 57.56 b 61.38 b 63.44 b<br />

Pseudotsuga menziesii 2.45 a 6.01 a 12.17 a 18.89 a 23.07 a 25.43 a 25.98 a<br />

Pseudotsuga menziesii+PEG 4.05 b 8.66 b 14.76 b 21.15 b 25.29 b 27.09 b 27.09 b<br />

Lolium perenne 3.80 a 9.10 a 21.10 a 31.74 a 39.80 a 43.30 a 44.90 a<br />

Lolium perenne + PEG 3.81 a 9.53 a 21.93 a 33.53 a 41.23 a 44.13 a 45.22 a<br />

Calluna vulgaris 3.30 a 6.90 a 12.57 a 22.38 a 27.43 a 29.54 a 30.92 a<br />

Calluna vulgaris + PEG 4.31 b 9.19 b 15.28 b 25.97 b 30.65 b 31.64 b 32.98 b<br />

Chamaenerion angustifolium 2.21 a 4.44 a 10.14 a 19.18 a 23.98 a 25.82 a 26.10 a<br />

Chamaenerion angustifolium + PEG 3.02 b 6.89 b 15.58 b 25.39 b 32.08 b 34.46 b 34.74 b<br />

Luzula sylvatica 2.69 a 5.67 a 11.22 a 19.48 a 24.96 a 27.56 a 28.37 a<br />

Luzula sylvatica EG 3.04 a 6.38 a 12.63 a 21.38 a 26.45 a 28.85 a 29.68 a<br />

Pinus sylvestris 2.75 a 5.80 a 12.30 a 21.85 a 26.63 a 27.91 a 28.46 a<br />

Pinus sylvestris PEG 3.27 b 6.83 b 13.54 b 22.99 b 27.99 b 29.54 b 30.35 b<br />

Picea sitchensis 2.97 a 6.23 a 10.18 a 16.04 a 19.91 a 20.90 a 21.44 a<br />

Picea sitchensis + PEG 4.07 b 8.71 b 14.85 b 19.92 b 23.27 b 24.81 b 24.81 b<br />

Acer pseudoplatanus 2.46 a 4.66 a 8.65 a 18.39 a 32.74 a 41.34 a 45.24 a<br />

Acer pseudoplatanus + PEG 2.73 b 4.67 a 8.66 a 18.42 a 32.96 a 41.40 a 45.44 a<br />

Vaccinum myrtillus 1.86 a 4.27 a 8.67 a 14.42 a 18.76 a 20.53 a 21.06 a<br />

Vaccinum myrtillus + PEG 2.69 b 6.75 b 13.10 b 19.75 b 23.87 b 25.94 b 26.48 b<br />

Juncus effusus 1.08 a 2.73 a 5.60 a 16.36 a 26.75 a 34.79 a 37.50 a<br />

Juncus effuses + PEG 1.10 a 3.04 a 6.49 b 18.74 b 31.18 b 37.12 b 39.59 b<br />

SE Difference 0.09 0.15 0.23 0.32 0.47 0.51 0.53<br />

Means with different superscripts for the same species in the same column and the same hour are statistically different<br />

(P L. perenne >A. pseudoplatanus

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from Scotland 316<br />

> L. sylvatica > P. sylvestris > J. effusus > V. myrtillus > P. sitchensis > P. menziesii > C. vulgaris<br />

>F. sylvatica (Table 4).<br />

Table 3: Degradation characteristics <strong>of</strong> the Scottish plant species as described by p = a + b (1-e -ct )<br />

Species a b c RSD A B (A+B)<br />

Fagus sylvatica 19.4 11.3 0.0325 0.447 16.4 14.3 30.7<br />

Brassica oleracea 37.2 62.8 0.1077 5.839 62.3 37.7 100<br />

Pseudotsuga menziesii 26.3 19.7 0.0516 1.643 32.7 13.3 46.0<br />

Lolium perenne 11.5 80.4 0.0671 6.114 32.3 60.3 92.6<br />

Calluna vulgaris 12.0 31.7 0.0374 1.443 10.4 32.1 42.5<br />

Chamaenerion angustifolium 6.5 91.5 0.0440 8.352 24.2 73.8 98.0<br />

Luzula sylvatica 10.0 56.2 0.0178 4.117 16.1 50.0 66.1<br />

Pinus sylvestris 18.7 41.1 0.0366 2.193 20.9 38.9 59.8<br />

Picea sitchensis 27.6 18.8 0.0401 1.303 24.5 21.9 46.4<br />

Acer pseudoplatanus 10.9 62.5 0.0831 3.809 27.5 45.9 73.4<br />

Vaccinum myrtillus 18.3 37.9 0.0387 3.717 18.6 37.6 56.2<br />

Juncus effusus 7.5 59.2 0.0179 1.608 16.7 50.0 66.7<br />

a = solubility and small particle loss<br />

b = insoluble but fermentable fraction<br />

c = rate constant.<br />

A = Washing loss (%)<br />

B = Degradation <strong>of</strong> water insoluble (%)<br />

A+B = Potential degradability (%)<br />

Table 4: Ranking <strong>of</strong> Scottish species according to in vitro gas production, DMD and in vivo digestibility<br />

Species Ranking <strong>of</strong> 48hr invitro Ranking <strong>of</strong> 48hr Ranking <strong>of</strong> in vivo<br />

Gas<br />

DMD<br />

digestibilty<br />

Fagus sylvatica 3 (33.69) 12 (27.70) 8 (36.81)<br />

Brassica oleracea 1 (55.75) 1 (100.00) 1 (77.83)<br />

P. menziesii 10 (23.07) 10 (43.79) 9 (35.38)<br />

Lolium perenne 2 (40.61) 3 (87.84) 2 (71.96)<br />

Calluna vulgaris 6 (27.43) 11 (38.65) 6 (45.15)<br />

Chamaenerion angustifolium 5 (32.08) 2 (90.61) 10 (34.66)<br />

Luzula sylvatica 9 (26.45) 5 (54.77) 5 (47.72)<br />

Pinus sylvestris 8 (26.63) 6 (53.64) 12 (33.28)<br />

Picea sitchensis 11 (19.91) 9 (43.82) 3 (58.13)<br />

Acer pseudoplatanus 4 (32.74) 4 (70.91) 11 (34.40)<br />

Vaccinum myrtillus 12 (18.76) 8 (50.90) 7 (36.88)<br />

Juncus effusus 7 (26.75) 7 (50.93) 4 (48.44)<br />

The ranking is shown from the highest to the lowest (1 to 12) with the actual values in brackets<br />

Species had significant effect on the in vivo DM digestibility <strong>of</strong> the forage species. B. oleracea<br />

had the highest % (77.83) in vivo DM digestibilty as observed with in vitro gas production and in<br />

sacco DM degradability. P. sylvestris had the lowest in vivo digestibility (33.28%). The ranking <strong>of</strong> the<br />

forages in terms <strong>of</strong> in vivo DM digestibility was B. oleracea (77.83%) > L. perenne > (72.00%) > P.<br />

sitchensis (58.13%) > J. effusus (48.44) > L. sylvatica (47.72) > C. vulgaris (45.15%) > V. myrtillus<br />

(36.88%) > F. sylvatica (36.81%) > P. menziesii (35.38%) > C. angustifolium (34.66%) > A.<br />

pseudoplatanus (34.40) > P. sylvestris (33.28%). The ranking <strong>of</strong> the species according to in vitro gas<br />

production, DMD and in vivo digestibility is shown in Table 4. Some plant species (B. oleracea, P.<br />

menziesii and L. perenne) showed consistency / position in the three rankings.<br />

There was a high positive correlation co-efficient between gas production and in sacco. DM<br />

degradability at both 48hr and 72hr (0.72 and 0.71 respectively). The correlation co-efficient <strong>of</strong> the<br />

relationship between 12hr in vitro gas production and in vivo digestibility was 0.71 while that <strong>of</strong> 16hr<br />

in sacco. DM degradability and in vivo digestibility was 0.71. The correlation co-efficient <strong>of</strong> 48hr in

317 Odeyinka, S.M, Hector, B.L and Ørskov, E.R<br />

vitro gas production and in vivo digestibility was 0.65 while that <strong>of</strong> 48hr in sacco. DM degradability<br />

and in vivo digestibility was 0.51. Either in vitro gas or Dmd can be used to predict in vivo digestibility.<br />

The increase in gas production with the addition <strong>of</strong> PEG (P

Nutritive Evaluation <strong>of</strong> Some Trees and Browse Species from Scotland 318<br />

References<br />

[1] Adugna, T., Khazaal, K., and Ørskov, E.R. (1997). Nutritive evaluation <strong>of</strong> some browse<br />

species. Animal Feed Science and Technology 67: 181-195.<br />

[2] Apori, S.O., Castro, F.B., Shand, W.J., and Ørskov, E.R. (1998). Chemical composition, in<br />

sacco degradation and in vitro gas production <strong>of</strong> some Ghanaian browse plants. Animal Feed<br />

Science and Technology 76: 129-137.<br />

[3] Badran, A.M. and Jones, D.E. (1965). Polyethylene glycol- tannin interaction in extracting<br />

enzyme. Nature, 206: 622-623<br />

[4] Blummel, M., Makkar, H.P.S., and Becker, K. (1990). In vitro gas production: a technique<br />

revisited. J. Anim. Physiol and Anim. Nutr. 77: 24-34<br />

[5] Blummel, M. and Ørskov, E. R. (1993). Comparison <strong>of</strong> in vitro gas production and nylon bag<br />

degradability <strong>of</strong> roughages in prediction <strong>of</strong> feed intake in cattle. Animal Feed Science and<br />

Technology 40, 109-119.<br />

[6] Devendra, C; (1990). The use <strong>of</strong> shrubs and tree fodders by ruminants. In: Shrubs and Tree<br />

fodders for Farm Animals, proceedings <strong>of</strong> a workshop in Denpasar, Indonesia 24-29 July,<br />

IDRC, Ottawa, Canada, pp. 42-60.<br />

[7] Jones, W.T. and Mangan, J.L. (1977). Complexes <strong>of</strong> the condensed tannins <strong>of</strong> sainfoin with<br />

fraction 1 leaf protein and with submaxillary mucoproteins and their reversal by polyethylene<br />

glycol and p H J . Sci Food Agric., 28: 126-136.<br />

[8] Khazaal, K., Markantonatos, X., Nastis, A. and Orskov, E.R. (1993). Changes with maturity in<br />

fibre composition and levels <strong>of</strong> extractable poly phenols in Greek browse: Effects on in vitro<br />

gas production and in sacco DM degradation. J. Sci. Food Agric., 63: 237-244<br />

[9] Kibbon, A. and Ørskov, E.R. (1993). The use <strong>of</strong> degradation characteristics <strong>of</strong> browse plants to<br />

predict intake and digestibility by goats. Anim. Prod. 57: 247- 251.<br />

[10] Kumar, R. and Vaithiyanathan, S. (1990). Occurrence, nutritional significance and effect on<br />

animal productivity <strong>of</strong> tannins in tree leaves. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech., 30: 21-38.<br />

[11] Menke, K., Raab, L., Salewski, A., Steingass, H., Fritz, D. and Schneider, W. (1979). The<br />

estimation <strong>of</strong> digestibility and metabolizable energy content <strong>of</strong> ruminant feedstuffs from the gas<br />

production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. J. Agric. Sci., Camb. 3: 217-<br />

222.<br />

[12] Odeyinka, S.M., Hector, B.L., Ørskov, E.R. (2003). Evaluation <strong>of</strong> the nutritive value <strong>of</strong> the<br />

browse species Gliricidia sepium (Jacq). Walp, Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit. and<br />

Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp from Nigeria. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Animal and Feed Sciences, 12: 341-349<br />

[13] Ørskov, E. R. (2000). New concepts <strong>of</strong> feed evaluation for Ruminants with Emphasis on<br />

Roughages and Feed intake. Asian - Australian J. Anim. Sci 13: 128-136<br />

[14] Ørskov , E.R and McDonald, I., (1979). The estimation <strong>of</strong> protein degradability in the rumen<br />

from incubation measurements weighted according to the rate <strong>of</strong> passage. J. Agric. Sci., Camb.<br />

92: 499-503.<br />

[15] Ørskov E.R., Hovell F.D.DeB., Mould F., 1980. The use <strong>of</strong> the nylon bag technique for the<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> feedstuffs. Trop. Anim. Prod. 5, 195-213<br />

[16] Ørskov, E. R., Reid, G.W., and Kay, M.M. (1988). Prediction <strong>of</strong> intake by cattle from<br />

degradation characteristics <strong>of</strong> roughages. Animal Production 46: 29-34<br />

[17] Ørskov E.R., Ryle M., (1990). Energy Nutrition in Ruminants. Elsevier Applied Science,<br />

London, UK pp 133-144<br />

[18] Sundstoøl, F., Homb, T., Ekern, A. and Breirem, K (1986). Sammensetning og Naeringsverdi<br />

av Norske Formidler. K.K. Heje Lommehandbok, P. F. Steensballes Forlag.<br />

[19] Van Soest, P.J. (1983). Nutritional Ecology <strong>of</strong> the Ruminant O and B Books, Corvalis<br />

[20] Woodword, A. and Reed, J.D. (1989). The influence <strong>of</strong> polyphenolics on the nutritive value <strong>of</strong><br />

browse: a summary <strong>of</strong> research conducted at ILCA. ILCA Bull. 35: 2-11

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

ISSN 1450-216X Vol.14 No.3 (2006), pp. 319-325<br />

© Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s Publishing, Inc. 2006<br />

http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm<br />

Determination <strong>of</strong> Sample Size<br />

Nadia Saeed<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics, GC University (GCU)<br />

Lahore (Pakistan)<br />

E-mail: nadia_gcu@yahoo.com<br />

Muhammad Khalid Pervaiz<br />

Chairperson, Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics<br />

GC University (GCU), Lahore (Pakistan)<br />

E-mail: drkhalidpervaiz@hotmail.com<br />

Muhammad Qaiser Shahbaz<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics, GC University (GCU)<br />

Lahore (Pakistan)<br />

E-mail: drshahbaz@gcu.edu.pk<br />

Abstract<br />

The sample size determination is one <strong>of</strong> the most frequent problems in the<br />

discipline <strong>of</strong> Statistics. Although standard formulae are available for determining sample<br />

size in many situations, yet specific methodology is lacking. The purpose <strong>of</strong> the paper is to<br />

highlight the factors involved in determining a desirable sample size for a research project.<br />

The paper <strong>of</strong>fers the brief review <strong>of</strong> determining the sample size under varying situations.<br />

Some new formulae are also developed with special reference <strong>of</strong> cost function and degree<br />

<strong>of</strong> affordable error.<br />

Key Words: Sample size, error, clinical trials, power analysis and cost function.<br />

1. Introduction<br />

The size <strong>of</strong> the sample is not only an essential element in every statistical procedure but it is also an<br />

item <strong>of</strong> great economic importance. In a sample survey, a statistician must determine the sample size.<br />

Statistical studies (surveys, experiments, observational studies, etc.) are always better when they are<br />

carefully planned. Good planning has many aspects. The study must be <strong>of</strong> adequate size, relative to the<br />

goals <strong>of</strong> the study. Sample size is important for economic reasons: An under-sized study can be a waste<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources for not having the capability to produce useful results, while an over-sized one uses more<br />

resources than are necessary (Mace, 1964; Kraemer & Thiemann, 1987; Cohen, 1988; Desu &<br />

Raghavarao, 1990; Lipsey, 1990; Shuster, 1990; and Odeh & Fox, 1991).<br />

The points to be considered while selecting a sample size are:<br />

i) Parameter: The population parameters to be estimated like mean the difference between<br />

means or proportion.<br />

ii) Variance: The samples are taken to form estimates <strong>of</strong> some characteristics <strong>of</strong> interest, like<br />

determination <strong>of</strong> mean in simple random sampling, stratified random sampling and cluster<br />

sampling. Most <strong>of</strong> the work has been done to determine the sample size based on precision to

Determination <strong>of</strong> Sample Size 320<br />

minimize the variance. (Greenland, 1988; Samuels, 1992; Buderer, 1996; Satten & Kupper,<br />

1990; Streiner, 1994 and Beal, 1989).<br />

iii) Issues and Prior Information: If the process has been studied before, then the prior<br />

information can be used to reduce sample sizes. This can be done by using prior mean and<br />

variance estimates and by stratifying the population to reduce variation within groups. Increase<br />

in sample size may reduce the sampling error but may cause increase in non-sampling error.<br />

iv) Clinical Trials: At the planning stage <strong>of</strong> a clinical trial a key question is "How many patients<br />

do we need?” This requires a sample size that ensures sufficient statistical power to detect a<br />

clinically relevant improvement. Sample size must be planned carefully to ensure that the<br />

research time, patient effort & support and costs invested in any clinical trial are not wasted.<br />

v) Power Analysis: power analysis and sample size estimation is an important aspect <strong>of</strong><br />

experimental design, because without these calculations, sample size may be too high or too<br />

low. If sample size is too low, the experiment will lack the precision to provide reliable answers<br />

to the questions it is investigating. If sample size is too large, time and resources will be wasted,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten for minimal gain.<br />

vi) Cost: The cost <strong>of</strong> sampling issue helps to determine how precise the estimate should be. When<br />

choosing sample sizes, it is required to select risk values (affordable error). If the decisions<br />

made from the sampling activity are very valuable, then these will have low risk values and<br />

hence larger sample sizes. So some cost functions in different situations have been discussed.<br />

Choosing the sample size is a problem faced by anyone doing a survey <strong>of</strong> any type. ‘What<br />

sample size do I need?’ is one <strong>of</strong> the most frequently asked questions to the statisticians. The response<br />

always starts “It depends on...” The sample size must depend on what you want to know about and<br />

how well you want to know about it. In order to make rational sample size choices, both the quantities<br />

to be estimated and the precision required must be specified.<br />

Sample-size planning is very important and almost always difficult. It requires care in eliciting<br />

scientific objectives and in obtaining suitable quantitative information prior to the study. Successful<br />

resolution <strong>of</strong> the sample-size problem requires the close and honest collaboration <strong>of</strong> statisticians and<br />

subject-matter experts (Russell, 2001).<br />

Sample-size problems are context-dependent. For example, how important it is to increase the<br />

sample size to account for such uncertainty depends on practical and ethical criteria. Moreover, sample<br />

size is not always the main issue; it is only one aspect <strong>of</strong> the quality <strong>of</strong> a study design (Russell, 2001).<br />

The objective <strong>of</strong> the paper is to mention available literature relevant to the determination <strong>of</strong><br />

sample size under various situations and to develop new formulae with reference to cost and affordable<br />

error.<br />

2. Sample size Estimation<br />

In this Section a review <strong>of</strong> above mentioned points is given with reference to estimating parameters,<br />

right variance, issues <strong>of</strong> interest, clinical trials, effect size, and power analysis.<br />

2.1. Parameters<br />

Chochran (1977) had given the simplest case for determination <strong>of</strong> sample size is concerned with<br />

infinite normal population with known variance. Desu and Raghavarao (1990) had provided brief<br />

review on sample size methodology. Further more the paired sample approach is employed by Dupont,<br />

(1988); Parker & Bregman, (1986); Nam, (1992); Lu & Bean, (1995); Lachenbruch, (1992); Lachin,<br />

(1992); Royston, (1993); Nam, (1997). A brief review has been given in literature to determine the<br />

sample size for the tests <strong>of</strong> proportions by Chochran, 1977; Casagrande, Pike & Smith, 1978; Feigl,<br />

1978; Haseman, 1978; Fleiss, 1981; Lemeshow, Hosmer & Klar, 1988; O’Neill, 1984; Thomas, 1992;<br />

Whitehead, 1993 and Gordon & Watson, 1996 for infinite population.

321 Nadia Saeed, Muhammad Khalid Pervaiz and Muhammad Qaiser Shahbaz<br />

2.2. Variance<br />

Another situation exists when someone is interested to find the right variance (Birkett & Day, 1994;<br />

Gould, 1995; Browne, 1995; Shih & Zhao, 1997) since some <strong>of</strong> the power functions usually involve<br />

parameters unrelated to the hypotheses. Most notably, they <strong>of</strong>ten involve one or more variances. For<br />

instance we need to know the residual variance <strong>of</strong> the measurements in the planned two-sample<br />

experiments, there may be substantial uncertainty in variance estimates obtained from historical or<br />

pilot data. There is some literature on dealing with variation in pilot data; a good starting point is<br />

Taylor and Muller (1995). Also, Muller and Benignus (1992) and Thomas (1997) discuss various<br />

simpler ways <strong>of</strong> dealing with these issues, such as sensitivity analyses.<br />

2.3. Issues and Prior Information<br />

At times the researcher has no choice about sample size. Often a study has limited budget. Sample size<br />

determination is an important issue because not all sample-size problems are the same, nor is sample<br />

size equally important in all studies. For example, the ethical issues in an opinion poll are very<br />

different from those in a medical experiment, and the consequences <strong>of</strong> an over or under-sized study<br />

also differ. Additional complications can hold for attribute data due to failures <strong>of</strong> asymptotic tests and<br />

inability to achieve a stated size due to discreteness or unusual situations such as inferences about rare<br />

attributes (Wright, 1997) and in case <strong>of</strong> Poisson and logistic regression (Whittemore, 1981; Hsieh,<br />

1989; Flack & Eudey, 1993; Bull, 1993 and Signorini, 1991). There are numerous articles, especially<br />

in biostatistics journals, concerning sample-size determination for specific tests like tests <strong>of</strong> continuous<br />

variables (Cohen, 1969; Pearson & Hartley, 1970 and Day & Graham, 1991). The extent to which<br />

sample size is adequate or inadequate in published studies provided by Freiman, Chalmers, Smith, and<br />

Kuebler, (1986). They worked on the importance <strong>of</strong> beta, the type-II error and sample size in the<br />

design and interpretation <strong>of</strong> the randomized controlled trial. Sample size determination can be done<br />

with the help <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>twares. There is a growing amount <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>tware for sample-size determination,<br />

including Query Advisor (Elash<strong>of</strong>f, 2000), PASS (Hintze, 2000), UnifyPow (O’Brien, 1998), and<br />

Power and Precision (Borenstein, 1997). Similarly Web resources include a comprehensive list <strong>of</strong><br />

power-analysis s<strong>of</strong>tware and online calculators (Thomas, 1998; Lenth, 2000). Wheeler (1974) provided<br />

some useful approximations for use in linear models; Castelloe (2000) gave an up-to-date overview <strong>of</strong><br />

computational methods.<br />

Though it is an important issue with respect to Statistics, social sciences and natural sciences<br />

but there is surprisingly small amount <strong>of</strong> published literature. One step in the sample size problem<br />

requires eliciting an effect size <strong>of</strong> scientific interest. It is not up to statistical consultant to decide this;<br />

however, it is his responsibility to try to elicit this information from the researchers involved in<br />

planning the study. Boen & Zahn (1982) discussed some <strong>of</strong> the human dynamics involved in<br />

discussing sample size (mostly as distinct from effect size). They suggested asking directly for an<br />

upper bound on sample size, relating that most clients will respond readily to this question.<br />

2.4. Clinical Trials<br />

Adequate sample size can help to ensure academically interesting result, whether or not a statistically<br />

significant difference is eventually found in the study (Eng & Siegelman, 1997). There is a need to<br />

know that how certain study design characteristics affect sample size and how to calculate sample size<br />

for several simple study designs, which are discussed in different scientific fields especially in clinical<br />

trials (Eng, 2003). An inadequate sample size also has ethical implications. If a study is not designed to<br />

include enough individuals to adequately test the research hypothesis, then the study unethically<br />

exposes individuals to the risks and discomfort <strong>of</strong> the research even though there is no potential for<br />

scientific gain. Although the connection between research ethics and adequate sample size has been<br />

recognized for at least 25 years (Newell, 1978), the performance <strong>of</strong> clinical trials with inadequate

Determination <strong>of</strong> Sample Size 322<br />

sample sizes remains widespread (Halpern, Karlawish & Berlin, 2002). So Rosner, (2000) described<br />

some Practical Consequences <strong>of</strong> Mathematical Properties.<br />

2.5. Power Analysis<br />

In sample size calculations, appropriate values for the smallest meaningful difference and the estimated<br />

SD are <strong>of</strong>ten difficult to obtain. In this case, power refers to the sensitivity <strong>of</strong> the study to enable<br />

detection <strong>of</strong> a statistically significant difference <strong>of</strong> the magnitude observed in the study. This activity,<br />

known as retrospective power analysis, is sometimes performed to aid in the interpretation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

statistical results <strong>of</strong> a study. If the results were not statistically significant, the investigator might<br />

explain the result as being due to a low power. So a lot <strong>of</strong> work is available in literature on power<br />

analysis by Detsky & Sackett (1985); Lubin & Gail (1990); Roebruck & Kuhn (1995); Thomas (1997);<br />

Castelloe (2000); Lenth (2001); Hoenig & Heisey (2001); Feiveson (2002).<br />

3. Cost Function and Degree <strong>of</strong> Affordable Error<br />

In this section, some new formulae for estimating sample size by changing affordable error in cost<br />

function have been developed.<br />

Let us have a cost function<br />

C C0<br />

C1n<br />

+ =<br />

Where ‘ C ’ is total cost, C 0 is overhead cost and C 1 is cost per unit.<br />

2<br />

Further suppose that the affordable error is <strong>of</strong> the form ε ( y − Y )<br />

The expected loss for a sample <strong>of</strong> size ‘n’ will be:<br />

2<br />

S ( n)<br />

= E[<br />

C]<br />

+ E ε ( y − Y )<br />

2<br />

εS<br />

S(<br />

n)<br />

= C0<br />

+ C1n<br />

+<br />

n<br />

2<br />

2 S<br />

Where E(<br />

y − Y ) =<br />

n<br />

After partially differentiating S (n) with respect to ‘n’ we can get:<br />

2<br />

1/<br />

2<br />

1 ⎟⎟<br />

⎛ εS<br />

⎞<br />

n = ⎜<br />

⎝ C ⎠<br />

Similarly if error function is changed to ε y − Y with the similar cost function, then sample<br />

size can be determined as:<br />

⎛ 2εS<br />

⎞<br />

n = ⎜<br />

5 ⎟<br />

⎝ C1<br />

⎠<br />

2 / 3<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The authors would like to thank Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Khalid Aftab, Vice Chancellor GCU for his anonymous<br />

support behind all the research activities in GC University, Lahore (Pakistan).

323 Nadia Saeed, Muhammad Khalid Pervaiz and Muhammad Qaiser Shahbaz<br />

References<br />

[1] Beal SL. Sample Size Determination for Confidence Intervals on the Population Mean and on<br />

the Difference Between Two Population Means. Biometrics 1989; 45:969-77.<br />

[2] Birkett MA, Day SJ. Internal Pilot Studies for Estimating Sample Size. Statistics in<br />

Medicine1994; 13:2455-2463.<br />

[3] Boen, J. R. and Zahn, D. A. (1982), The Human Side <strong>of</strong> Statistical Consulting, Lifetime<br />

Learning Publications, Belmont, CA.<br />

[4] Borenstein, M., Rothstein, H., and Cohen, J. (1997), Power and Precision, Biostat, Teaneck, NJ,<br />

S<strong>of</strong>tware for MS-DOS systems.<br />

[5] Browne RH. On the use <strong>of</strong> a Pilot Sample for Sample Size Determination. Statistics in<br />

Medicine 1995; 14:1933-1940.<br />

[6] Buderer NMF. Statistical Methodology: I. Incorporating the Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Disease into the<br />

Sample Size Calculation for Sensitivity and Specificity. Academic Emergency Medicine 1996;<br />

3:895-900.<br />

[7] Bull SB. Sample Size and Power Determination for a Binary Outcome and an Ordinal Exposure<br />

when Logistic Regression Analysis is Planned. American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 1993;<br />

137:676-684.<br />

[8] Castelloe, J. (2000), “Sample Size Computations and Power Analysis with the SAS System,” in<br />

Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Twenty-Fifth Annual SAS User’s Group International Conference, Cary,<br />

NC, SAS Institute, Inc., Paper 265-25.<br />

[9] Casagrande JT, Pike MC, Smith PG. An Improved Approximate Formula for Calculating<br />

Sample Sizes for Comparing Two Binomial Distributions. Biometrics 1978; 34:483-486.<br />

[10] Chochran, W.G., Sampling Technque s, John Wiley & Sonns, New York, (1977).<br />

[11] Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Academic Press,<br />

1969.<br />

[12] Cohen, J. (1988), Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Academic Press, New<br />

York, 2 nd ed.<br />

[13] Day SJ, Graham DF. Sample Size Estimation for Comparing Two or More Treatment Groups<br />

in Clinical Trials. Statistics in Medicine 1991; 10:33-43.<br />

[14] Detsky AS, Sackett DL. When was a "negative" clinical trial big enough? How many patients<br />

do you need depends on what you have found? Arch Intern Med 1985; 145:709.<br />

[15] Desu, M. M. and Raghavarao, D. (1990), Sample Size Methodology, Academic Press, Boston.<br />

[16] Dupont WD. Power Calculations for Matched Case-Control Studies. Biometrics 1988;44:1157-<br />

1168<br />

[17] Elash<strong>of</strong>f, J. (2000), nQuery Advisor Release 4.0, Statistical Solutions, Cork, Ireland, S<strong>of</strong>tware<br />

for MS-DOS systems.<br />

[18] Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology 2003;<br />

227:309.<br />

[19] Eng J, Siegelman SS. Improving radiology research methods: what is being asked and who is<br />

being studied? Radiology 1997; 205:651-655.<br />

[20] Feiveson AH. Power by simulation. STATA J 2002; 2:107.<br />

[21] Feigl P. A Graphical Aid for Determining Sample Size When Comparing Two Independent<br />

Proportions. Biometrics 1978; 34:111-122.<br />

[22] Flack VF, Eudey TL. Sample Size Determinations Using Logistic Regression with Pilot Data.<br />

Statistics in Medicine 1993; 12:1079-1084.<br />

[23] Freiman, J. A., Chalmers, T. C., Smith, Jr., H., and Kuebler, R. R. (1986), “The Importance <strong>of</strong><br />

Beta, the Type II Error, and Sample Size in the Design and Interpretation <strong>of</strong> the Randomized<br />

Controlled Trial: Survey <strong>of</strong> 71 “Negative” Trials,” in Medical Uses <strong>of</strong> Statistics, eds. J. C.<br />

Bailar III and F. Mosteller, chap. 14, pp. 289–304, NEJM Books, Waltham, Mass.<br />

[24] Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Second Edition. New York: Wiley &<br />

Sons, 1981.

Determination <strong>of</strong> Sample Size 324<br />

[25] Gould AL. Planning and Revising the Sample Size for a Trial. Statistics in Medicine<br />

1995;14:1039-1051<br />

[26] Greenland S. On Sample -size and Power Calculations for Studies Using Confidence Intervals.<br />

American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 1988; 128:231-237.<br />

[27] Halpern SD, Karlawish JHT, Berlin JA. The continuing unethical conduct <strong>of</strong> underpowered<br />

clinical trials. JAMA 2002; 288:358-362.<br />

[28] Hintze, J. (2000), PASS 2000, Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, UT, S<strong>of</strong>tware<br />

for MS-DOS systems.<br />

[29] Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse <strong>of</strong> power: the pervasive fallacy <strong>of</strong> power calculations for<br />

data analysis. Am Stat 2001; 55:19.<br />

[30] Hsieh FY. Sample Size Tables for Logistic Regression. Statistics in Medicine 1989; 8:795-802.<br />

[31] Kraemer, H. C. and Thiemann, S. (1987), How Many Subjects? Statistical Power Analysis in<br />

<strong>Research</strong>, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.<br />

[32] Lachenbruch PA. On the Sample Size for Studies Based Upon McNemar’s Test. Statistics in<br />

Medicine 1992; 11:1521-1525.<br />

[33] Lachin JM. Power and Sample Size Evaluation for the McNemar Test with Application to<br />

Matched Case-Control Studies. Statistics in Medicine 1992; 11:1239-1251.<br />

[34] Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Klar J. Sample Size Requirements for Studies Estimating Odds<br />

Ratios or Relative Risks. Statistics in Medicine 1988; 7:759-764.<br />

[35] Lenth RV. Some practical guidelines for effective sample size determination. Am Stat 2001;<br />

55:187.<br />

[36] Lenth, R. V. (2000), “Java applets for power and sample size,”<br />

http://www.stat.uiowa.edu/~rlenth/ Power/.<br />

[37] Lipsey, M. W. (1990), Design Sensitivity: Statistical Power for Experimental <strong>Research</strong>, Sage<br />

Publications, Newbury Park, CA<br />

[38] Lubin JH, Gail MH. On Power and Sample Size for Studying Features <strong>of</strong> the Relative Odds <strong>of</strong><br />

Disease. American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 1990;131:552-66.<br />

[39] Lu Y, Bean JA. On the Sample Size for One-Sided Equivalence <strong>of</strong> Sensitivities Based Upon<br />

McNemar’s Test. Statistics in Medicine 1995; 14:1831-1839.<br />

[40] Mace, A. E. (1964), Sample-size determination, Reinhold, New York.<br />

[41] Muller, K. E. and Benignus, V. A. (1992), “Increasing scientific power with statistical power,”<br />

Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 14, 211–219.<br />

[42] Nam JM. Sample Size Determination for Case-Control Studies and the Comparison <strong>of</strong><br />

Stratified and Unstratified Analyses. Biometrics 1992; 48:389-395.<br />

[43] Nam JM. Establishing Equivalence <strong>of</strong> Two Treatments and Sample Size Requirements in<br />

Matched-Pairs Design. Biometrics 1997; 53:1422-30.<br />

[44] Newell DJ. Type II errors and ethics (letter). BMJ 1978; 4:1789.<br />

[45] O’Brien, R. G. (1998), UnifyPow.sas Version 98.08.25, Department <strong>of</strong> Biostatistics and<br />

Epidemiology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, Available for download from<br />

http://www.bio.ri.ccf. org/power.html.<br />

[46] Odeh, R. E. and Fox, M. (1991), Sample Size Choice: Charts for Experiments with Linear<br />

Models, Marcel Dekker, New York, second ed.<br />

[47] O’Neill RT. Sample Sizes for Estimation <strong>of</strong> the Odds Ratio in Unmatched Case-Control<br />

Studies. American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 1984; 120:145-153.<br />

[48] Parker RA, Bregman DJ. Sample Size for Individually Matched Case-Control Studies.<br />

Biometrics 1986; 42: 919-926.<br />

[49] Pearson ES, Hartley HO. Biometrika Tables for Statisticians. Third Edition. Cambridge:<br />

Cambridge University Press, 1970 (Volume I).<br />

[50] Roebruck P, Kuhn A. Comparison <strong>of</strong> Tests and Sample Size Formulae for Proving Therapeutic<br />

Equivalence Based on the Difference <strong>of</strong> Binomial Probabilities. Statistics in Medicine 1995;<br />

14:1583-1594.

325 Nadia Saeed, Muhammad Khalid Pervaiz and Muhammad Qaiser Shahbaz<br />

[51] Rosner B. Fundamentals <strong>of</strong> biostatistics 5th ed. Pacific Grove, Calif: Duxbury, 2000; 308.<br />

[52] Royston P. Exact Conditional and Unconditional Sample Size for Pair-Matched Studies with<br />

Binary Outcome: A Practical Guide. Statistics in Medicine 1993; 12:699-712.<br />

[53] Russell V. Lenth (2001), some practical guidelines for effective sample-size determination.<br />

[54] Samuels ML, Lu TFC. Sample Size Requirement for the Back-<strong>of</strong>-the-Envelope Binomia l<br />

Confidence Interval. American Statistician 1992; 46:228-231.<br />

[55] Satten GA, Kupper LL. Sample Size Requirements for Interval Estimation <strong>of</strong> the Odds Ratio.<br />

American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 1990; 131:177-84.<br />

[56] Shih WJ, Zhao PL. Design for Sample Size Re-estimation with Interim Data for Double Blind,<br />

Clinical Trials with Binary Outcomes. Statistics in Medicine 1997; 16:1913-1923.<br />

[57] Shuster, J. J. (1990), CRC Handbook <strong>of</strong> Sample Size Guidelines for Clinical Trials, CRC Press,<br />

Boca Raton.<br />

[58] Signorini DF. Sample Size for Poisson Regression. Biometrika 1991; 78:446-450.<br />

[59] Singh, D., Chaudhary, F.S., Sample Survey Desins, New Age International Publishers, New<br />

Delhi, (1968).<br />

[60] Streiner DL. Sample -Size Formulae for Parameter Estimation. Perceptual and Motor Skills<br />

1994; 78:275-84.<br />

[61] Thomas, L. (1998), “Statistical power analysis s<strong>of</strong>tware,” http://www.forestry.ubc.ca/<br />

conservation/power/.<br />

[62] Thomas, L. (1997), “Retrospective Power Analysis,” Conservation Biology, 11, 276–280.<br />

[63] Thomas RG, Conlon M. Sample Size Determination Based on Fisher’s Exact Test for Use in 2<br />

2 Comparative Trials with Low Event Rates. Controlled Clinical Trials 1992; 13: 134-147.<br />

[64] Taylor, D. J. and Muller, K. E. (1995), “Computing Confidence Bounds for Power and Sample<br />

Size <strong>of</strong> theGeneral Linear Univariate Model,” The American Statistician, 49, 43–47.<br />

[65] Wheeler, R. E. (1974), “Portable Power,” Techno metrics, 16, 193–201.<br />

[66] Whitehead J. Sample Size Calculations for Ordered Categorical Data. Statistics in Medicine<br />

1993; 12:2257-2271.<br />

[67] Whittemore AS. Sample Size for Logistic Regression with Small Response Probability. <strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> the American Statistical Association 1981; 76:27-32<br />

[68] Wright, T. (1997), “A simple algorithm for tighter exact upper confidence bounds with rare<br />

attributes in finite universes,” Statistics and Probability Letters, 36, 59–67. 11

<strong>European</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

ISSN 1450-216X Vol.14 No.3 (2006), pp. 326-332<br />

© Euro<strong>Journal</strong>s Publishing, Inc. 2006<br />

http://www.eurojournals.com/ejsr.htm<br />

Model-Based Adaptive Chaos Control using Lyapunov<br />

Exponents<br />

Amin Yazdanpanah Goharrizi<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineering<br />

K. N. Toosi University <strong>of</strong> Technology<br />

Tehran, Iran<br />

Mehdi Semin<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Electrical Engineering<br />

Tabriz University, Tabriz, Iran<br />

E-mail: yazdanpanah@ee.kntu.ac.ir<br />

Abstract<br />

A model-based approach to adaptive control <strong>of</strong> chaos in non-linear chaotic discrete<br />

time systems is presented. In the case <strong>of</strong> unknown or time varying chaotic plants, the<br />

Lyapunov exponents may vary during the plant operation. In this paper, an effective<br />

adaptive strategy is proposed for on-line identification <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents. The control<br />

aim is that the plant output changes in accordance with the output <strong>of</strong> the linear desired<br />

model. Also, a nonlinear observer for estimation <strong>of</strong> the states is proposed. Simulation<br />

results are provided to show the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the proposed methodology.<br />

1. Introduction<br />

The analysis and control <strong>of</strong> chaotic behavior in dynamical systems has been widely investigated in<br />

recent years [1], [2], [3], [4] and [5].Also, Lyapunov exponents have been used to characterize and<br />

quantify the chaoticity <strong>of</strong> complex dynamical systems [6], and the computation <strong>of</strong> the Lyapunov<br />

exponents for nonlinear dynamical systems is an effective tool in this respect [7]. In [8], a model-based<br />

approach for anticontrol <strong>of</strong> some discrete-time systems is proposed and in this paper, a reverse method<br />

for control <strong>of</strong> chaotic systems is presented and also, a new method to adaptive control <strong>of</strong> chaos via<br />

adaptive calculation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents is introduced. The adaptive calculation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov<br />

exponents proposed in [9-10-11], greatly facilities the design <strong>of</strong> adaptive chaos control. Thus, a<br />

generalized adaptive algorithm recursive least square for estimation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents is<br />

developed when the parameters <strong>of</strong> the system change abruptly. We use an efficient QR based method<br />

for the computation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents [12]. Then, if the maximum Lyapunov exponent becomes<br />

positive it's indicates the chaotic behavior and the control aim is that the plant output changes in<br />

accordance with the output <strong>of</strong> the linear desired model. So, the behavior <strong>of</strong> the closed-loop system<br />

depends on the linear model and it can be periodic or tends to zero after controlling. With the above<br />

strategy and adaptive calculation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents an efficient methodology for adaptive chaos<br />

control is presented. Also, a nonlinear observer is proposed when the sate <strong>of</strong> nonlinear chaotic plant are<br />

not available. Finally, simulation results for Henon map with time varying parameters are provided to<br />

show the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> the proposed methodology.

Model-Based Adaptive Chaos Control using Lyapunov Exponents 327<br />

2. Adaptive Estimation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov Exponents<br />

Consider a nonlinear discrete-time dynamical system given by<br />

n<br />

⎪⎧<br />

x(<br />

k + 1)<br />

= f [ x(<br />

k)]<br />

x(<br />

k)<br />

∈ R<br />

⎨<br />

⎪⎩ x0<br />

− given<br />

(1)<br />

Where f is assumed to be continuously differentiable, at least locally in a region <strong>of</strong> interest<br />

and k = 0,<br />

1,...<br />

is the number <strong>of</strong> the sampling instants. Each <strong>of</strong> the scalar state variables in the nonlinear<br />

discrete-time dynamical system given by equation (1), can be rewritten in the following form<br />

T<br />

x j ( k + 1)<br />

= ϕ 1 j ( k)<br />

θ1<br />

+ ϕ2<br />

j ( k)<br />

θ 2 + ... + ϕij<br />

( k)<br />

θi<br />

= ϕ j ( k)<br />

θ j k = 0,<br />

1,...<br />

j = 1,...,<br />

n<br />

,<br />

,<br />

Where, x j are the scalar state variables, θ ij s are parameters to be determined, and ϕ ij s are<br />

known functions that may depend on other known variables. The vectors<br />

T<br />

ϕ ( k)<br />

= [ ϕ ( k)<br />

ϕ ( k)<br />

... ϕ ( k)]<br />

j<br />

1 j<br />

2 j<br />

ij<br />

θ j = ( θ1<br />

j θ2<br />

j ...<br />

T<br />

θij<br />

)<br />

(2)<br />

have also been introduced. By invoking the recursive least square (RLS) algorithm, the parameters <strong>of</strong><br />

the model in (2) can be updated recursively [13]:<br />

ˆ ˆ<br />

T<br />

θ ( ) ( 1)<br />

( )[ ( ) ( ) ˆ<br />

j k = θ j k − + K k x j k −ϕ<br />

j k θ j ( k −1)]<br />

(3)<br />

Where<br />

T<br />

−1<br />

K ( k ) = P(<br />

k −1)<br />

ϕ j ( k )[ λI<br />

+ ϕ j ( k ) P(<br />

k −1)<br />

ϕ j ( k )]<br />

(4)<br />

And<br />

T<br />

P ( k ) = [ I − K ( k ) ϕ j ( k )] P ( k − 1)<br />

/ λ<br />

(5)<br />

And, λ is the forgetting factor and I is an i × i identity matrix. Let J k be the Jacobian matrix<br />

<strong>of</strong> (1) which is updated at each iteration by adaptive calculation <strong>of</strong> the system parameters. It is shown<br />

that the QR-factorization <strong>of</strong> the matrix product J m J m−<br />

1...J1<br />

gives the Lyapunov exponents <strong>of</strong> the plant<br />

in equation (1). This process is started with Q 0 = I , and is as follows:<br />

qr[<br />

J J ... J ] = qr[<br />

J J ... J ( J Q )] =<br />

qr[<br />

J<br />

qr[<br />

J<br />

qr[<br />

J<br />

m<br />

m<br />

m<br />

m<br />

J<br />

J<br />

J<br />

m−1<br />

m−1<br />

m−1<br />

m−1<br />

... J<br />

...( J Q )][ R R ] = ...<br />

... J<br />

1<br />

3<br />

i<br />

( J Q )][ R ] =<br />

3<br />

Q<br />

2<br />

2<br />

i−1<br />

1<br />

][ R<br />

m<br />

2<br />

i−1<br />

R<br />

m−1<br />

1<br />

1<br />

i−<br />

2<br />

... R<br />

2<br />

2<br />

R<br />

1<br />

1<br />

0<br />

] = ...<br />

Qm<br />

[ Rm<br />

... R2<br />

R1]<br />

= Qm<br />

R<br />

(6)<br />

Where, qr[.] denotes the QR-factorization process. Starting with J 1 , at each step, a pre-<br />

B J Q followed by a QR-factorization <strong>of</strong> = J Q − = Q R i = 1,<br />

2,...,<br />

m is<br />

multiplication i = i i−1<br />

performed. Matrix R is the product <strong>of</strong> the matrices ... R2R1<br />

Bi i i 1 i i,<br />

Rm obtained in this sequential manner.<br />

Furthermore, each <strong>of</strong> the diagonal elements <strong>of</strong> R is simply the product <strong>of</strong> the corresponding diagonal<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> all the<br />

,<br />

s . Hence, approximation to the n Lyapunov exponents are provided as:<br />

R i<br />

m 1<br />

λ j = lim ∑ ln Ri<br />

( j,<br />

j)<br />

j = 1,<br />

2,...,<br />

n<br />

m→∞<br />

m i=<br />

1<br />

(7)<br />

Since the Jacobian matrix <strong>of</strong> (1) is updated at each iteration, the Lyapunov exponents <strong>of</strong> the<br />

system are calculated adaptively at each iteration.

328 Amin Yazdanpanah Goharrizi and Mehdi Semin<br />

3. Design Methodology<br />

l<br />

Let the controlled dynamical system (1), with the input sequence u( k)<br />

∈ R , be as follows:<br />

x ( k + 1)<br />

= f [ x(<br />

k)]<br />

+ u(<br />

k)<br />

(8)<br />

For this system finding a feedback control law u ( k)<br />

= g[<br />

x(<br />

k)]<br />

, where g: R R<br />

n → is an<br />

appropriate function such that the resulting closed loop system exhibits appropriate behavior, is<br />

desired. So, consider the linear desired model is as follows:<br />

x ( k + 1)<br />

= Ax(<br />

k)<br />

(9)<br />

n<br />

n×<br />

n<br />

Where x ∈ R , A∈<br />

R is a constant matrix and k = 0,<br />

1,<br />

2,...<br />

is the discrete time index. So, the<br />

controlled system orbit can behave like the system model "(9)," depends on how the eigenvalues <strong>of</strong> the<br />

matrix A is chosen. If the eigenvalues lie in the unit disc then the control action is like a regulation<br />

problem but if the eigenvalues are on the unit disc the behavior <strong>of</strong> the closed loop system becomes<br />

periodic. So, it's sufficient to choose the appropriate control input as follows:<br />

u ( k)<br />

= − f [ x(<br />

k)]<br />

+ Ax(<br />

k)<br />

Then, the methodology is as follows:<br />

(10)<br />

⎧0<br />

u(<br />

k)<br />

= ⎨<br />

⎩−<br />

f [ x(<br />

k)]<br />

+ Ax(<br />

k)<br />

if λmax<br />

< 0<br />

if λmax<br />

> 0<br />

(11)<br />

The control action can be applied by adaptive calculation <strong>of</strong> Lyapunov exponents <strong>of</strong> the system,<br />

as discussed in the pervious section.<br />

4. Nonlinear Observer Design Methodology<br />

Consider the controlled nonlinear chaotic system as follows:<br />

x(<br />

k + 1)<br />

= f [ x(<br />

k),<br />

u(<br />

k)]<br />

y(<br />

k)<br />

= h[<br />

x(<br />

k)]<br />

(12)<br />

n<br />

where f : ℜ<br />

p ≤ n .<br />

n<br />

n<br />

→ ℜ , and h : ℜ<br />

p<br />

→ ℜ are assumed to be differentiable and smooth functions and<br />

An observer is a dynamic system driven by the observations which is shown in figure (1):<br />

xˆ ( k + 1)<br />

= f [ xˆ<br />

( k),<br />

u(<br />

k)]<br />

+ L(<br />

k)[<br />

h(<br />

x)<br />

− h(<br />

xˆ<br />

)]<br />

In the case <strong>of</strong> state estimation, we have<br />

(13)<br />

lim[ xˆ<br />

( k)<br />

− x(<br />

k)]<br />

→ 0<br />

k →∞<br />

An approach to the observer design for system (12) is:<br />

(14)<br />

J ( x(<br />

k + 1),<br />

xˆ<br />

( k + 1))<br />

≤ ∆ when k > k ∗<br />

(15)<br />

With some nonnegative function J , and threshold value ∆ > 0 .

Model-Based Adaptive Chaos Control using Lyapunov Exponents 329<br />

Figure 1: The Nonlinear observer.<br />

Substituting x ( k + 1)<br />

and x ˆ ( k + 1)<br />

from (12) and (13) into (15), and using the gradient method<br />

for computing the gain <strong>of</strong> observer we have:<br />

L( k + 1)<br />

= L(<br />

k)<br />

− α∇<br />

( ( 1),<br />

ˆ<br />

L(<br />

k ) J x k + x(<br />

k + 1))<br />

(16)<br />

Where, α > 0 . Algorithm (16) makes the current observer gain correction<br />

∆ L( k)<br />

= L(<br />

k + 1)<br />

− L(<br />

k)<br />

in the descent direction <strong>of</strong> the current goal function J .<br />

5. Simulation Results<br />

+<br />

u<br />

k<br />

+<br />

+<br />

Chaotic<br />

Plant<br />

Z -1<br />

xˆ k + 1<br />

k<br />

fˆ<br />

( ⋅)<br />

Consider the Henon map as:<br />

2<br />

xk<br />

+ 1 = yk<br />

+ 1−<br />

axk<br />

yk<br />

+ 1 = bxk<br />

(17)<br />