Introductory notes to the Semiotics of Music - Philip Tagg's home page

Introductory notes to the Semiotics of Music - Philip Tagg's home page

Introductory notes to the Semiotics of Music - Philip Tagg's home page

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

General semiotic concepts P Tagg: <strong>Introduc<strong>to</strong>ry</strong> <strong>notes</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Semiontics <strong>of</strong> <strong>Music</strong> 11<br />

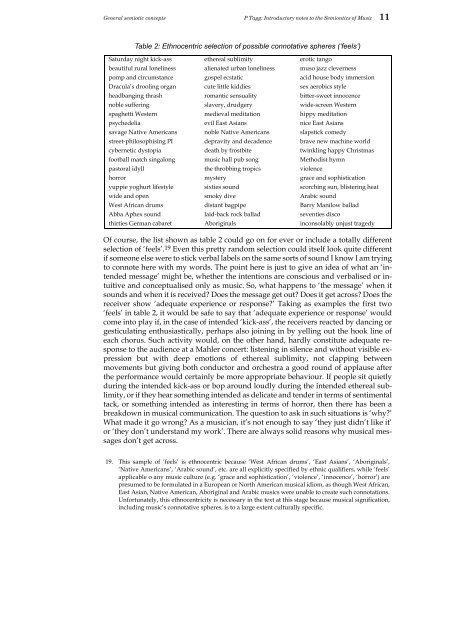

Table 2: Ethnocentric selection <strong>of</strong> possible connotative spheres (‘feels’)<br />

Saturday night kick-ass e<strong>the</strong>real sublimity erotic tango<br />

beautiful rural loneliness alienated urban loneliness muso jazz cleverness<br />

pomp and circumstance gospel ecstatic acid house body immersion<br />

Dracula’s drooling organ cute little kiddies sex aerobics style<br />

headbanging thrash romantic sensuality bitter-sweet innocence<br />

noble suffering slavery, drudgery wide-screen Western<br />

spaghetti Western medieval meditation hippy meditation<br />

psychedelia evil East Asians nice East Asians<br />

savage Native Americans noble Native Americans slapstick comedy<br />

street-philosophising PI depravity and decadence brave new machine world<br />

cybernetic dys<strong>to</strong>pia death by frostbite twinkling happy Christmas<br />

football match singalong music hall pub song Methodist hymn<br />

pas<strong>to</strong>ral idyll <strong>the</strong> throbbing tropics violence<br />

horror mystery grace and sophistication<br />

yuppie yoghurt lifestyle sixties sound scorching sun, blistering heat<br />

wide and open smoky dive Arabic sound<br />

West African drums distant bagpipe Barry Manilow ballad<br />

Abba Aphex sound laid-back rock ballad seventies disco<br />

thirties German cabaret Aboriginals inconsolably unjust tragedy<br />

Of course, <strong>the</strong> list shown as table 2 could go on for ever or include a <strong>to</strong>tally different<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> ‘feels’. 19 Even this pretty random selection could itself look quite different<br />

if someone else were <strong>to</strong> stick verbal labels on <strong>the</strong> same sorts <strong>of</strong> sound I know I am trying<br />

<strong>to</strong> connote here with my words. The point here is just <strong>to</strong> give an idea <strong>of</strong> what an ‘intended<br />

message’ might be, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> intentions are conscious and verbalised or intuitive<br />

and conceptualised only as music. So, what happens <strong>to</strong> ‘<strong>the</strong> message’ when it<br />

sounds and when it is received? Does <strong>the</strong> message get out? Does it get across? Does <strong>the</strong><br />

receiver show ‘adequate experience or response?’ Taking as examples <strong>the</strong> first two<br />

‘feels’ in table 2, it would be safe <strong>to</strong> say that ‘adequate experience or response’ would<br />

come in<strong>to</strong> play if, in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> intended ‘kick-ass’, <strong>the</strong> receivers reacted by dancing or<br />

gesticulating enthusiastically, perhaps also joining in by yelling out <strong>the</strong> hook line <strong>of</strong><br />

each chorus. Such activity would, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, hardly constitute adequate response<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience at a Mahler concert: listening in silence and without visible expression<br />

but with deep emotions <strong>of</strong> e<strong>the</strong>real sublimity, not clapping between<br />

movements but giving both conduc<strong>to</strong>r and orchestra a good round <strong>of</strong> applause after<br />

<strong>the</strong> performance would certainly be more appropriate behaviour. If people sit quietly<br />

during <strong>the</strong> intended kick-ass or bop around loudly during <strong>the</strong> intended e<strong>the</strong>real sublimity,<br />

or if <strong>the</strong>y hear something intended as delicate and tender in terms <strong>of</strong> sentimental<br />

tack, or something intended as interesting in terms <strong>of</strong> horror, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re has been a<br />

breakdown in musical communication. The question <strong>to</strong> ask in such situations is ‘why?’<br />

What made it go wrong? As a musician, it’s not enough <strong>to</strong> say ‘<strong>the</strong>y just didn’t like it’<br />

or ‘<strong>the</strong>y don’t understand my work’. There are always solid reasons why musical messages<br />

don’t get across.<br />

19. This sample <strong>of</strong> ‘feels’ is ethnocentric because ‘West African drums’, ‘East Asians’, ‘Aboriginals’,<br />

‘Native Americans’, ‘Arabic sound’, etc. are all explicitly specified by ethnic qualifiers, while ‘feels’<br />

applicable o any music culture (e.g. ‘grace and sophistication’, ‘violence’, ‘innocence’, ‘horror’) are<br />

presumed <strong>to</strong> be formulated in a European or North American musical idiom, as though West African,<br />

East Asian, Native American, Aboriginal and Arabic musics were unable <strong>to</strong> create such connotations.<br />

Unfortunately, this ethnocentricity is necessary in <strong>the</strong> text at this stage because musical signification,<br />

including music’s connotative spheres, is <strong>to</strong> a large extent culturally specific.