alfred 2 - University of Winchester

alfred 2 - University of Winchester

alfred 2 - University of Winchester

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

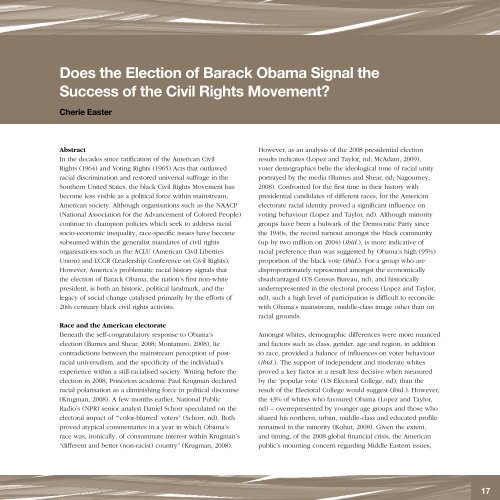

Does the Election <strong>of</strong> Barack Obama Signal the<br />

Success <strong>of</strong> the Civil Rights Movement?<br />

Cherie Easter<br />

Abstract<br />

In the decades since ratification <strong>of</strong> the American Civil<br />

Rights (1964) and Voting Rights (1965) Acts that outlawed<br />

racial discrimination and restored universal suffrage in the<br />

Southern United States, the black Civil Rights Movement has<br />

become less visible as a political force within mainstream,<br />

American society. Although organisations such as the NAACP<br />

(National Association for the Advancement <strong>of</strong> Colored People)<br />

continue to champion policies which seek to address racial<br />

socio-economic inequality, race-specific issues have become<br />

subsumed within the generalist mandates <strong>of</strong> civil rights<br />

organisations such as the ACLU (American Civil Liberties<br />

Union) and LCCR (Leadership Conference on Civil Rights).<br />

However, America’s problematic racial history signals that<br />

the election <strong>of</strong> Barack Obama, the nation’s first non-white<br />

president, is both an historic, political landmark, and the<br />

legacy <strong>of</strong> social change catalysed primarily by the efforts <strong>of</strong><br />

20th centuary black civil rights activists.<br />

Race and the American electorate<br />

Beneath the self-congratulatory response to Obama’s<br />

election (Barnes and Shear, 2008; Montanaro, 2008), lie<br />

contradictions between the mainstream perception <strong>of</strong> postracial<br />

universalism, and the specificity <strong>of</strong> the individual’s<br />

experience within a still-racialised society. Writing before the<br />

election in 2008, Princeton academic Paul Krugman declared<br />

racial polarisation as a diminishing force in political discourse<br />

(Krugman, 2008). A few months earlier, National Public<br />

Radio’s (NPR) senior analyst Daniel Schorr speculated on the<br />

electoral impact <strong>of</strong> “‘color-blurred’ voters” (Schorr, nd). Both<br />

proved atypical commentaries in a year in which Obama’s<br />

race was, ironically, <strong>of</strong> consummate interest within Krugman’s<br />

“different and better (non-racist) country” (Krugman, 2008).<br />

However, as an analysis <strong>of</strong> the 2008 presidential election<br />

results indicates (Lopez and Taylor, nd; McAdam, 2009),<br />

voter demographics belie the ideological tone <strong>of</strong> racial unity<br />

portrayed by the media (Barnes and Shear, nd; Nagourney,<br />

2008). Confronted for the first time in their history with<br />

presidential candidates <strong>of</strong> different races, for the American<br />

electorate racial identity proved a significant influence on<br />

voting behaviour (Lopez and Taylor, nd). Although minority<br />

groups have been a bulwark <strong>of</strong> the Democratic Party since<br />

the 1940s, the record turnout amongst the black community<br />

(up by two million on 2004) (ibid.), is more indicative <strong>of</strong><br />

racial preference than was suggested by Obama’s high (95%)<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> the black vote (ibid.). For a group who are<br />

disproportionately represented amongst the economically<br />

disadvantaged (US Census Bureau, nd), and historically<br />

underrepresented in the electoral process (Lopez and Taylor,<br />

nd), such a high level <strong>of</strong> participation is difficult to reconcile<br />

with Obama’s mainstream, middle-class image other than on<br />

racial grounds.<br />

Amongst whites, demographic differences were more nuanced<br />

and factors such as class, gender, age and region, in addition<br />

to race, provided a balance <strong>of</strong> influences on voter behaviour<br />

(ibid.). The support <strong>of</strong> independent and moderate whites<br />

proved a key factor in a result less decisive when measured<br />

by the ‘popular vote’ (US Electoral College, nd), than the<br />

result <strong>of</strong> the Electoral College would suggest (ibid.). However,<br />

the 43% <strong>of</strong> whites who favoured Obama (Lopez and Taylor,<br />

nd) – overrepresented by younger age groups and those who<br />

shared his northern, urban, middle-class and educated pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

remained in the minority (Kohut, 2008). Given the extent,<br />

and timing, <strong>of</strong> the 2008 global financial crisis, the American<br />

public’s mounting concern regarding Middle Eastern issues,<br />

17