Read the COW Magazine Online - Creative COW Magazine

Read the COW Magazine Online - Creative COW Magazine

Read the COW Magazine Online - Creative COW Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

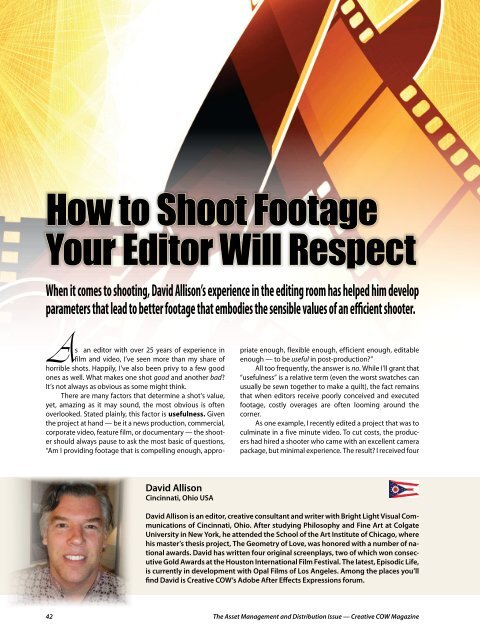

How to Shoot Footage<br />

Your Editor Will Respect<br />

When it comes to shooting, David Allison’s experience in <strong>the</strong> editing room has helped him develop<br />

parameters that lead to better footage that embodies <strong>the</strong> sensible values of an efficient shooter.<br />

A s an editor with over 25 years of experience in<br />

film and video, I’ve seen more than my share of<br />

horrible shots. Happily, I’ve also been privy to a few good<br />

ones as well. What makes one shot good and ano<strong>the</strong>r bad?<br />

It’s not always as obvious as some might think.<br />

There are many factors that determine a shot’s value,<br />

yet, amazing as it may sound, <strong>the</strong> most obvious is often<br />

overlooked. Stated plainly, this factor is usefulness. Given<br />

<strong>the</strong> project at hand — be it a news production, commercial,<br />

corporate video, feature film, or documentary — <strong>the</strong> shooter<br />

should always pause to ask <strong>the</strong> most basic of questions,<br />

“Am I providing footage that is compelling enough, appro-<br />

42<br />

David Allison<br />

Cincinnati, Ohio USA<br />

priate enough, flexible enough, efficient enough, editable<br />

enough — to be useful in post-production?”<br />

All too frequently, <strong>the</strong> answer is no. While I’ll grant that<br />

“usefulness” is a relative term (even <strong>the</strong> worst swatches can<br />

usually be sewn toge<strong>the</strong>r to make a quilt), <strong>the</strong> fact remains<br />

that when editors receive poorly conceived and executed<br />

footage, costly overages are often looming around <strong>the</strong><br />

corner.<br />

As one example, I recently edited a project that was to<br />

culminate in a five minute video. To cut costs, <strong>the</strong> producers<br />

had hired a shooter who came with an excellent camera<br />

package, but minimal experience. The result? I received four<br />

David Allison is an editor, creative consultant and writer with Bright Light Visual Communications<br />

of Cincinnati, Ohio. After studying Philosophy and Fine Art at Colgate<br />

University in New York, he attended <strong>the</strong> School of <strong>the</strong> Art Institute of Chicago, where<br />

his master’s <strong>the</strong>sis project, The Geometry of Love, was honored with a number of national<br />

awards. David has written four original screenplays, two of which won consecutive<br />

Gold Awards at <strong>the</strong> Houston International Film Festival. The latest, Episodic Life,<br />

is currently in development with Opal Films of Los Angeles. Among <strong>the</strong> places you’ll<br />

find David is <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>COW</strong>’s Adobe After Effects Expressions forum.<br />

The Asset Management and Distribution Issue — <strong>Creative</strong> <strong>COW</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

and a half hours of material, 25 minutes of which was useable.<br />

Let me repeat that: I received four and a half hours of<br />

material to edit a five-minute video — bad enough — yet<br />

only 25 minutes of it was even remotely useful!!! (Fade-up<br />

scream SFX.)<br />

To say that <strong>the</strong> decision to hire an inexpensive shooter<br />

cost more money than it saved would be an understatement.<br />

Without going into too much detail, just ponder <strong>the</strong><br />

extra time I spent making data space for 4½ hours of material,<br />

ingesting 4½ hours of material, reviewing 4½ hours of<br />

material, culling shots from 4½ hours of material, dealing<br />

with system sluggishness brought on by 4½ hours of material<br />

etc., etc. so on and so forth, multiplied by seventeen days<br />

of editing.<br />

Is it any wonder why I eventually decided to put gripes<br />

like this down on paper?<br />

In addition to being an editor, I’ve also experienced<br />

what it’s like to be a director, producer, writer, and, yes, a<br />

shooter. I’ve studied under people who’ve studied under<br />

Orson Welles. I’ve worked in <strong>the</strong> realm of <strong>the</strong> avant-garde<br />

with figures of varying quirkiness, such as Peter Kubelka<br />

and P. Adams Sitney. I’ve logged long hours with A-list, commercial<br />

directors who’ve agonized over <strong>the</strong> best way to sell<br />

donuts and cottage cheese.<br />

Through it all, I’ve developed a reasonably good feel<br />

for The Big Picture: Why are we all doing what we are doing?<br />

What particulars help (or hurt) <strong>the</strong> process that leads to <strong>the</strong> end<br />

goal?<br />

When it comes to shooting, my experience in <strong>the</strong> editing<br />

room has helped me develop parameters that lead to<br />

better footage. While I tend not to think of <strong>the</strong>se parameters<br />

as rigid or static (we’re not talking “The Ten Commandments”<br />

here), a list of common problems — and common<br />

solutions — has naturally taken form over <strong>the</strong> years. I eventually<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>the</strong> list under one umbrella, which I fondly<br />

call: How to Shoot Video Your Editor Will Respect In <strong>the</strong> Morning.<br />

QUITTERS NEVER WIN (except in production)<br />

Imagine for a moment that you are in <strong>the</strong> editing room,<br />

watching your editor pore over some footage you shot.<br />

(You should always imagine this, by <strong>the</strong> way). Now let’s say<br />

you arrive at a series of tabletop product shots. In <strong>the</strong> first<br />

shot, you accidently “miss <strong>the</strong> landing pad” (or as Mary Lou<br />

Retton would say, you didn’t “stick it”).<br />

This is harmless enough. No shooters are automatons,<br />

and “sticking <strong>the</strong> landing” can be tricky business. The editor<br />

watches in silence as you stay with your final position for<br />

<strong>the</strong> traditional five seconds.<br />

Shot 2 comes along. Again, you don’t quite nail <strong>the</strong> final<br />

position, but dutifully stay with it — hoping that something<br />

salvageable might result.<br />

Shot 3 represents a variation on <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me: you miss<br />

<strong>the</strong> landing, but proceed to sneak back with <strong>the</strong> camera until<br />

you arrive at a flawlessly composed, final position.<br />

After ten similar attempts, just when evidence is developing<br />

that you’re getting closer and closer to <strong>the</strong> Holy<br />

Grail, <strong>the</strong> editor turns to you and says, “You know what your<br />

problem is? You never quit.”<br />

Hunh??! What’s that about?! You were always taught that<br />

quitters never win! Well, what’s going on here is that your<br />

well-mannered (and no doubt good-looking) editor is politely<br />

telling you that you are wasting valuable post-production<br />

time, and probably costing someone money, to boot.<br />

You see, unlike in <strong>the</strong> Olympic world of Mary Lou, if<br />

you don’t “stick” <strong>the</strong> landing, you can’t simply fling up your<br />

arms, arch your back, and hope <strong>the</strong> judges like your spunky<br />

exuberance. Dude, you repeatedly missed your mark (no<br />

sin), and <strong>the</strong>n chose to hang with <strong>the</strong> shot for five agonizingly<br />

long, utterly worthless seconds!<br />

While our example only demonstrates <strong>the</strong> loss of a<br />

minute of time, you should never lose sight of how quickly<br />

<strong>the</strong>se wasted minutes add up. The cumulative effect <strong>the</strong>se<br />

types of decisions can have on an edit session can be significant.<br />

What’s more, your reputation as a camera op will<br />

never be enhanced if you continually provide lengthy useless<br />

shot after lengthy useless shot.<br />

The same trouble can surface with a simple, rackfocus.<br />

If you miss your destination, immediately quit on <strong>the</strong><br />

shot. I mean, c’mon, tenacity may be a virtue, but addictive<br />

stubbornness surely is not. Efficiency is what results from<br />

common sense and determination, not super-human abilities.<br />

No shooter would ever be able to produce footage that<br />

leads to a 1:1 ratio, but every shooter is capable of eliminating<br />

those senseless frames of abject uselessness.<br />

NOT STICKING THE BEGINNING EITHER<br />

An inversion of <strong>the</strong> Quitters Never Win (except in postproduction)<br />

motif occurs when <strong>the</strong> beginning of a shot is<br />

flubbed, but <strong>the</strong> camera rolls on obliviously. I call this <strong>the</strong><br />

“I Didn’t Quite Catch <strong>the</strong> Beginning, But Let’s Roll With It Anyway”<br />

Syndrome.<br />

That 12 year-old genius who is happily flourishing in<br />

<strong>the</strong> local med school is your assignment du jour, but as she<br />

holds a hypodermic needle up to <strong>the</strong> natural light for a<br />

quick tap, you’re late establishing focus. No matter, you tell<br />

yourself, you’ll just keep following her as she strolls over to<br />

her patient and swabs down his arm.<br />

CUT to <strong>the</strong> post-pro suite, where your editor, upon<br />

viewing this near-miss of a spectacular shot, is screaming<br />

at <strong>the</strong> monitor, “Would it have killed you to ask her to stop<br />

and do it again?!!!!”<br />

Here, your stunningly-handsome editor is merely trying<br />

to remind you of <strong>the</strong> most important tool a shooter has<br />

at his or her disposal: A VOICE! Even when a director is calling<br />

<strong>the</strong> shots, your professionalism is elevated when you exhibit<br />

some responsibility for addressing small failures such<br />

as this.<br />

REWIND: you’re back in <strong>the</strong> hospital. You pull your eye<br />

away from <strong>the</strong> lens and interrupt <strong>the</strong> medical prodigy, “Excuse<br />

me, Dr. Jennifer-In-Training, but would mind terribly if<br />

I asked you to go back over to that window and tap that<br />

needle-thingy again? I missed it…”<br />

Jennifer obliges, <strong>the</strong> director nods approvingly, and<br />

soon, your editor will be salivating over <strong>the</strong> marvelously useful<br />

shot you just helped to manufacture.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r incarnation of <strong>the</strong> Quitters Never Win (except<br />

in post-production) motif is what I call The “I Know There’s a<br />

Drunk Peeing In <strong>the</strong> Background, But The University President<br />

Is Still Welcoming The Famous Actress Back to Campus” Di-<br />

<strong>Creative</strong> <strong>COW</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> — The Asset Management and Distribution Issue 43