Download the entire issue - American Association for Clinical ...

Download the entire issue - American Association for Clinical ...

Download the entire issue - American Association for Clinical ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

What are <strong>the</strong> three most important<br />

elements of safe process design?<br />

The first is accounting <strong>for</strong> human factors.<br />

It is important to recognize that processes<br />

which rely on perfect human per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

are incapable of high reliability. The second<br />

is standardization with limited discretionary<br />

variability (See “Examples,” below).<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, reasons <strong>for</strong> appropriate variation<br />

should be captured and fed into <strong>the</strong><br />

process design. The third is organizational<br />

culture. It is essential to have a positive reporting<br />

culture that exposes misses and<br />

near misses, because no process or procedure<br />

is failure-proof. Successful reporting<br />

cultures also identify key vulnerabilities.<br />

How do attitudes about safety in <strong>the</strong><br />

laboratory affect process design?<br />

All processes that rely on vigilance and hard<br />

work are incapable of per<strong>for</strong>ming at a high<br />

level of reliability. If leadership and/or <strong>the</strong><br />

front line worker do not understand <strong>the</strong><br />

limitations of human per<strong>for</strong>mance, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

high levels of reliability will not be possible.<br />

Also, a positive reporting culture is essential.<br />

Punishment <strong>for</strong> human error will impede<br />

process improvement and make <strong>the</strong><br />

organization less safe and less reliable.<br />

14 CliniCal laboratory news July 2011<br />

PATIENT SAFETY FOCUS<br />

TAkING AIM AT REDuCING LAB ERRORS<br />

Designing Processes <strong>for</strong> Patient Safety<br />

The Key is Finding <strong>the</strong> Vulnerabilities and Fixing Them<br />

richard gitomer, Md, Mba, is chief quality<br />

officer <strong>for</strong> emory university Hospital<br />

Midtown and is a general internist by<br />

training. He has led numerous improvement<br />

projects related to access, efficiency,<br />

and innovation in <strong>the</strong> ambulatory setting<br />

and care of patients with chronic conditions.<br />

dr. gitomer is a recognized leader<br />

in process improvement through his collaborations<br />

with <strong>the</strong> institute <strong>for</strong> Healthcare<br />

improvement and <strong>the</strong> association of<br />

american Medical Colleges.<br />

this inteRview was ConDuCteD By CoRinne Fantz, phD.<br />

<strong>Clinical</strong> laboratories routinely monitor<br />

key processes. Is it not enough to know<br />

what errors occur and why <strong>the</strong>y occur?<br />

Measurement alone does not result in improvement,<br />

but it is essential <strong>for</strong> identifying<br />

areas that need improvement and <strong>for</strong> monitoring<br />

improvement. There is a saying, “You<br />

don’t fatten <strong>the</strong> chicken by weighing it.” (See<br />

Figure, above).<br />

What opportunities and challenges do<br />

new technology bring to old processes?<br />

New technologies increase <strong>the</strong> capability of<br />

systems. For example, autoverification in<br />

<strong>the</strong> lab is faster and more reproducible than<br />

manual verification of results. But technology<br />

comes with some inherent risks. For<br />

those technologies that still require human<br />

intervention, <strong>the</strong> interface between humans<br />

and <strong>the</strong> technology remains <strong>the</strong> most<br />

vulnerable point. These vulnerabilities<br />

include incorrect human operation, due<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r to human error or errors that result<br />

from interacting with <strong>the</strong> new technology.<br />

All systems will fail at some point. With<br />

older technology, we know those failure<br />

modes and have designed processes to limit<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir impact. We do not have <strong>the</strong> same understanding<br />

of new technologies. So, until<br />

lab examples of standardization<br />

with limited variability<br />

® standardized procedures across all sites<br />

® standardized phlebotomy trays<br />

® one type of point- of-care glucometer in <strong>the</strong> health system<br />

® automation that limits <strong>the</strong> care providers choice of tube types<br />

® selection of a primary referral laboratory<br />

® use of templates <strong>for</strong> interpretative reports<br />

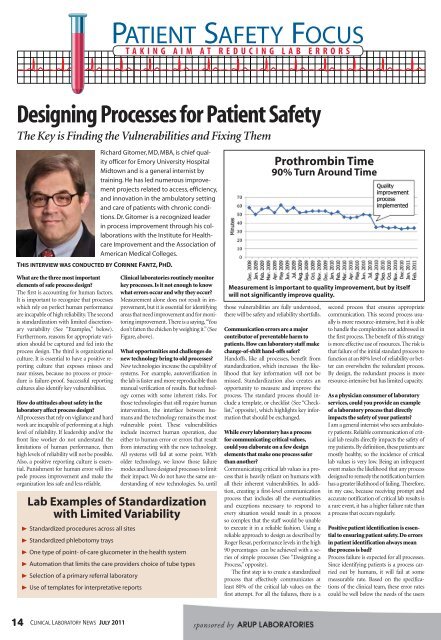

Prothrombin Time<br />

90% Turn around Time<br />

measurement is important to quality improvement, but by itself<br />

will not significantly improve quality.<br />

those vulnerabilities are fully understood,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re will be safety and reliability shortfalls.<br />

Communication errors are a major<br />

contributor of preventable harm to<br />

patients. How can laboratory staff make<br />

change-of-shift hand-offs safer?<br />

Handoffs, like all processes, benefit from<br />

standardization, which increases <strong>the</strong> likelihood<br />

that key in<strong>for</strong>mation will not be<br />

missed. Standardization also creates an<br />

opportunity to measure and improve <strong>the</strong><br />

process. The standard process should include<br />

a template, or checklist (See “Checklist,”<br />

opposite), which highlights key in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

that should be exchanged.<br />

While every laboratory has a process<br />

<strong>for</strong> communicating critical values,<br />

could you elaborate on a few design<br />

elements that make one process safer<br />

than ano<strong>the</strong>r?<br />

Communicating critical lab values is a process<br />

that is heavily reliant on humans with<br />

all <strong>the</strong>ir inherent vulnerabilities. In addition,<br />

creating a first-level communication<br />

process that includes all <strong>the</strong> eventualities<br />

and exceptions necessary to respond to<br />

every situation would result in a process<br />

so complex that <strong>the</strong> staff would be unable<br />

to execute it in a reliable fashion. Using a<br />

reliable approach to design as described by<br />

Roger Resar, per<strong>for</strong>mance levels in <strong>the</strong> high<br />

90 percentages can be achieved with a series<br />

of simple processes (See “Designing a<br />

Process,” opposite).<br />

The first step is to create a standardized<br />

process that effectively communicates at<br />

least 80% of <strong>the</strong> critical lab values on <strong>the</strong><br />

first attempt. For all <strong>the</strong> failures, <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

second process that ensures appropriate<br />

communication. This second process usually<br />

is more resource-intensive, but it is able<br />

to handle <strong>the</strong> complexities not addressed in<br />

<strong>the</strong> first process. The benefit of this strategy<br />

is more effective use of resources. The risk is<br />

that failure of <strong>the</strong> initial standard process to<br />

function at an 80% level of reliability or better<br />

can overwhelm <strong>the</strong> redundant process.<br />

By design, <strong>the</strong> redundant process is more<br />

resource-intensive but has limited capacity.<br />

As a physician consumer of laboratory<br />

services, could you provide an example<br />

of a laboratory process that directly<br />

impacts <strong>the</strong> safety of your patients?<br />

I am a general internist who sees ambulatory<br />

patients. Reliable communication of critical<br />

lab results directly impacts <strong>the</strong> safety of<br />

my patients. By definition, <strong>the</strong>se patients are<br />

mostly healthy, so <strong>the</strong> incidence of critical<br />

lab values is very low. Being an infrequent<br />

event makes <strong>the</strong> likelihood that any process<br />

designed to remedy <strong>the</strong> notification barriers<br />

has a greater likelihood of failing. There<strong>for</strong>e,<br />

in my case, because receiving prompt and<br />

accurate notification of critical lab results is<br />

a rare event, it has a higher failure rate than<br />

a process that occurs regularly.<br />

Positive patient identification is essential<br />

to ensuring patient safety. Do errors<br />

in patient identification always mean<br />

<strong>the</strong> process is bad?<br />

Process failure is expected <strong>for</strong> all processes.<br />

Since identifying patients is a process carried<br />

out by humans, it will fail at some<br />

measurable rate. Based on <strong>the</strong> specifications<br />

of <strong>the</strong> clinical team, <strong>the</strong>se error rates<br />

could be well below <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong> users