Creating Transformation: Ten principles for the - Central Europe

Creating Transformation: Ten principles for the - Central Europe

Creating Transformation: Ten principles for the - Central Europe

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Brigitte Scholz<br />

<strong>Creating</strong> <strong>Trans<strong>for</strong>mation</strong>:<br />

<strong>Ten</strong> <strong>principles</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Treatment of post-mining landscapes<br />

Dipl.-Ing. Brigitte Scholz<br />

Interim Professor<br />

Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus<br />

Department of Regional Planning<br />

Konrad-Wachsmann-Allee 1<br />

03046 Cottbus<br />

Germany<br />

Fon: +49 (0)355 69 2138<br />

Fax: +49 (0)355 69 3907<br />

Email: brigitte.scholz@tu-cottbus.de<br />

This project is implemented through <strong>the</strong> CENTRAL EUROPE Programme co-financed by <strong>the</strong> ERDF.<br />

www.resource-ce.eu<br />

Seite 1 von 8

The rehabilitation of <strong>for</strong>mer mines, industrial sites and brownfields are challenging<br />

tasks. The legacy of mining provides special problems, but also very unique<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> regional development. This was <strong>the</strong> starting point of an<br />

Internationale Bauausstellung (International Building Exhibition), a well known<br />

planning instrument in Germany. The article describes <strong>the</strong> background and aims of<br />

IBA and gives an outlook to future rehabilitation quality standards.<br />

1. Background: The region Lausitz-Spreewald<br />

For ten years <strong>the</strong> organization, International Bauausstellung (IBA) Fürst-Pückler-<br />

Land, has been active in shaping <strong>the</strong> post-mining landscape in Brandenburg (in<br />

eastern Germany). This region was known as <strong>the</strong> energy district of <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer<br />

German Democratic Republic because of its huge deposits of lignite. The excavation<br />

of lignite began around 150 years ago. Initially, mining was below ground but was<br />

later carried out by means of huge open-cast mines. Mining brought o<strong>the</strong>r industries<br />

such as briquette factories, power stations, coke plants and related branches of<br />

industry. A total of seventeen open-cast mines were in operation in 1989. Subsequent<br />

to <strong>the</strong> radical political change in 1989/1990, <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> open-cast mines and<br />

industries were abruptly shut down. Today <strong>the</strong> swedish energy firm, Vattenfall,<br />

operates five open-cast mines and three power stations in <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

As a result of this deindustrialization, <strong>the</strong> region has experienced a high rate of<br />

unemployment up to 25 Percent. The German government has devised new<br />

employment strategies <strong>for</strong> a limited time, so called job-creating measures. Also, <strong>the</strong><br />

whole political and social structure in <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mer GDR has changed, e.g. <strong>the</strong> school<br />

and <strong>the</strong> health care systems. The <strong>for</strong>mer Chancellor Helmut Kohl promoted<br />

“prosperous landscapes,” but in reality, <strong>the</strong> population in <strong>the</strong> eastern part of Germany<br />

has been shrinking. In 2005, <strong>the</strong> German Spatial Planning office documented <strong>the</strong><br />

simultaneity of growth and shrinkage in Germany. In Lusatia, <strong>the</strong> population has<br />

shrunk by about 20 percent since 1990.<br />

Normally, <strong>the</strong> recultivation of post-mining landscapes is an integral part of <strong>the</strong><br />

production process. For <strong>the</strong> closed-down lignite industry from GDR, legal mining<br />

responsiblity fell to <strong>the</strong> government as proprietor of <strong>the</strong> lignite business that could<br />

not be privatized. A company, LMBV (Lausitzer und Mitteldeutsche<br />

Bergbauverwaltungsgesellschaft), was set up to deal with this task. The german<br />

government allocated spezial funds <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> recultivation of <strong>the</strong> post-mining<br />

landscapes. A total of just under ten billion euros was budgeted yet. Also, IBA has<br />

been financed by this budget.<br />

2. IBA as an planning instrument<br />

In Germany, building exhibitions are a well known, project oriented planning<br />

method that provides new impulses within a limited time, guarantees a high-quality<br />

standard of (landscape) architecture and leads to innovative designs.<br />

The IBA Fürst-Pückler-Land Association, supported by four rural districts in<br />

Brandenburg as well as <strong>the</strong> city of Cottbus and promoted by <strong>the</strong> Federal Land<br />

Brandenburg, has been <strong>the</strong> heart of a network connecting <strong>the</strong> people involved on site<br />

Seite 2 von 8

with one ano<strong>the</strong>r and with national and international experts by means of a planningrelated<br />

target. IBA combined creative and technical innovation, called upon both <strong>the</strong><br />

sciences and arts to serve this objective, drawed international attention to <strong>the</strong> region -<br />

and thus created regional circular flows in terms of <strong>the</strong> economy and new jobs.<br />

Main Topics of IBA<br />

IBA Fürst-Pückler-Land has been engaged in a total of 30 projects that comprise a<br />

“Workshop <strong>for</strong> New Landscapes”. All projects are owned and operated by <strong>the</strong><br />

municipalities or independent associations <strong>the</strong>mselves, not by IBA. The philosophy<br />

of IBA aimed to enable <strong>the</strong> region to find new perspectives <strong>for</strong> regional<br />

development. IBA was dealing with seven main topics:<br />

Industrial heritage: The aim of IBA was not only to preserve outstanding examples<br />

of Lusatian industrial heritage, but also to invent new concepts <strong>for</strong> use at those sites.<br />

These monuments are important to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> identity of places and to give <strong>the</strong><br />

people a bridge between <strong>the</strong> region’s past and future. One pre-emiment example is a<br />

<strong>for</strong>mer conveyor bridge, which had been rededicated as <strong>the</strong> Visitors’ Mine F60.<br />

Originally constructed to remove <strong>the</strong> excavated earth above <strong>the</strong> lignite, this device –<br />

<strong>the</strong> biggest movable tool in <strong>the</strong> world – became redundant after only thirteen months<br />

of operation when <strong>the</strong> mine closed down. Today, several thousand of people each<br />

year visit <strong>the</strong> steel giant, <strong>the</strong> so called “horizontal Eiffel-Tower”, which is over 500<br />

metres long and 80 metres high. At night, a light and sound installation trans<strong>for</strong>ms<br />

<strong>the</strong> bridge again and turns it into a work of art. The Visitors’ Mine F60 and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

industrial momuments are connected by <strong>the</strong> ENERGY-Route of Lusatian Industrial<br />

Heritage, part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>an Route of Industrial Heritage, thus creating a unique<br />

tourism experience.<br />

Waterscapes: One main aspect of <strong>the</strong> post-mining landscape in Lusatia will be <strong>the</strong><br />

new surface water. The coal pits that have fallen into disuse – around 30 in <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

region – will be flooded to become lakes. The “heart” of <strong>the</strong> new “Lusatian<br />

Lakeland” is a chain of ten lakes over 35 kilometres long, linked by navigable canals.<br />

The emphasis of this successively emerging water landscape is on active and<br />

sporting recreation – from sailing and surfing to cycling, skating, riding and even<br />

golfing. Besides this, large areas are also reserved <strong>for</strong> quiet development in tune with<br />

nature. IBA developed <strong>the</strong> overall concept <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> new waterscape and invented a<br />

new hallmark of <strong>the</strong> Lusatian Lakeland, <strong>the</strong> floating houses. These houses will keep<br />

<strong>the</strong> shores free from construction and enable use of <strong>the</strong> lakes during <strong>the</strong> several years<br />

in which <strong>the</strong>y are being filled. The first three projects have already been realised, and<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r projects are planned. For example, IBA organised a competition <strong>for</strong> mobile<br />

floating architecture and developed a concept <strong>for</strong> a pontoon bridge. The Lusatian<br />

Lakeland will become a new tourist destination and a “hot spot” <strong>for</strong> regional<br />

development after mining. Although <strong>the</strong> flooding of <strong>the</strong> lakes will take until 2015,<br />

<strong>the</strong> new structures allow one to visit <strong>the</strong> region now.<br />

Energy Landscapes: The extensive, sparsely populated region provides ideal<br />

preconditions <strong>for</strong> electricity production from regenerative energy sources like wind,<br />

sun and biomass. IBA has been examining concepts <strong>for</strong> energy landscapes to<br />

combine different energy sources <strong>for</strong> a new, variably usable and ecologically<br />

enduring cultural landscape. In <strong>the</strong> project “Energy Landscape Welzow”, <strong>for</strong><br />

example, Brandenburg University of Technology has been investigating in<br />

cooperation with <strong>the</strong> mining companies, different agriculture and <strong>for</strong>estry systems in<br />

Seite 3 von 8

otation with plantations of wood <strong>for</strong> energy use. This wood is used <strong>for</strong> energyproduction<br />

<strong>for</strong> a settlement that had to be relocated to make way <strong>for</strong> mining, and now<br />

provides an example of a new energy standard.<br />

New Land: Open-cast mining allows one to shape newly filled-in landscapes with a<br />

new contour and new uses. IBA has been developing several different approaches <strong>for</strong><br />

post-mining landscapes to give <strong>the</strong>m a characteristic design - landscapes that do not<br />

represent a denial of mining and give <strong>the</strong> region outstanding examples of landscape<br />

architecture. One project that remained unrealised, addressed <strong>the</strong> possibility of<br />

maintaining a barren, bizarre post-mining landscape with its unique relief, a desert<br />

along with an oasis. This landscape would have been both a touristic attraction and a<br />

nature protection area. Misgivings and rejections of <strong>the</strong> unusual landscape concept<br />

among <strong>the</strong> population, as well as technical difficulties, led to <strong>the</strong> project’s<br />

abandonment. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> mining landscapes inspire artists from around <strong>the</strong><br />

world. Our project “Art-Landscape” tries to show, how land art could add to postmining<br />

landscape a new design and new impulses <strong>for</strong> regional development. This<br />

could also stimulate regeneration of small villages in post-mining landscapes, which<br />

are threatened by depopulation and an aging demographic.<br />

Border Landscapes: Besides <strong>the</strong> mining landcapes, <strong>the</strong> region offers ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

opportunity <strong>for</strong> regional development, <strong>the</strong> cross-border cooperation with Poland. The<br />

drawing of <strong>the</strong> border following <strong>the</strong> Second World War has separated cultural<br />

landscapes and towns that <strong>for</strong>merly belonged toge<strong>the</strong>r. IBA tried to reconnect <strong>the</strong>m<br />

and establish new structures, e.g. <strong>the</strong> international Geopark Muskau Coal Crescent.<br />

This landscape was <strong>for</strong>med by glaciers during <strong>the</strong> ice age and due to its resources of<br />

brown coal, mining started here in <strong>the</strong> 19 th century. Now, you can find a special<br />

cultural landscape that offers <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> tourism. IBA wanted to establish a<br />

German-Polish association to coordinate activities to this end. Special funds from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an Union have been offered <strong>for</strong> this project.<br />

Cityscapes: As I showed in <strong>the</strong> beginning, a huge decrease in population has resulted<br />

from <strong>the</strong> deindustrialization of <strong>the</strong> region. In particular, this affects <strong>the</strong> towns that<br />

had previously grown because of <strong>the</strong> industrialization, and which now, in turn, are<br />

shrinking. IBA has been accompanying <strong>the</strong> conversion of towns and demonstrating<br />

new approaches to demolition and <strong>the</strong> re-valuing of spaces. For example, a<br />

skyscraper was trans<strong>for</strong>med into five village clusters and a network of common areas<br />

were established. At <strong>the</strong> same time as <strong>the</strong> Lusatian IBA undertook <strong>the</strong>se projects,<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r IBA in <strong>the</strong> Federal Land Sachsen-Anhalt focussed on <strong>the</strong> challenge of urban<br />

redevelopment in shrinking regions. These projects were also presented in 2010.<br />

Transitional Landscapes: Open-cast mining results in desert- and canyon-like<br />

interim landscapes, which radiate a bizarre beauty. However, <strong>the</strong>se landscapes have a<br />

limited life span: They will disappear eventually. Through open-cast mining tours,<br />

IBA opened <strong>the</strong> possibility to experience <strong>the</strong>se landscapes, enabling visitors to<br />

discover new beauties in a landscape that has fundamentally changed and to open<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir minds to new developments (fig. 12). Thus, people had an opportunity to<br />

observe <strong>the</strong> process from mining to rehabilitation. This <strong>for</strong>m of tourism helps to<br />

close <strong>the</strong> gap between mining and post-mining and to initiates a tourism<br />

development.<br />

Seite 4 von 8

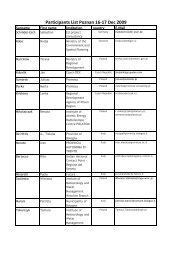

Fig. 1 IBA Projects (IBA-Archiv)<br />

Fig. 2 Lusatian Lakeland (Aerial Foto: Radke LMBV IBA-Archiv)<br />

Seite 5 von 8

3. <strong>Ten</strong> <strong>principles</strong> concerning <strong>the</strong> treatment of Post-Mining landscapes<br />

Based on IBA’s experiences, IBA has <strong>for</strong>mulated ten <strong>principles</strong> concerning <strong>the</strong><br />

treatment of post-mining landscapes. The aim is to establish a common<br />

understanding how to deal with post-mining landscape so that <strong>the</strong>y can serve as a<br />

precondition <strong>for</strong> new economic uses and gives future perspectives <strong>for</strong> people and<br />

enterprises. The premise of <strong>the</strong> <strong>principles</strong> is a worldwide obligation <strong>for</strong> sustainable<br />

development. This implies that in <strong>the</strong> development of post-mining landscapes, social,<br />

economic and ecological matters must be balanced. The overall concept is <strong>the</strong><br />

creation of a diverse, multifunctional post-mining landscape as a condition <strong>for</strong> new<br />

economic activities and future perspectives <strong>for</strong> people and enterprises in <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

Sustainable rehabilitation and development thus represent an added-value investment<br />

in <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

1. Setting an Example<br />

The development of a post-mining landscape must be exemplary. As a consciously<br />

planned treatment of a cultural landscape, <strong>the</strong> development has a model character<br />

and must contribute to <strong>the</strong> implementation of international goals and standards of<br />

sustainable development.<br />

2. Using Resources<br />

The legacy of mining, land, buildings, and infrastructures are industrial-heritage<br />

resources <strong>for</strong> a sustainable development. The preservation and re-use of typical<br />

components creates special places that shape <strong>the</strong> look of a region and bridge <strong>the</strong> past<br />

and <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

3. Fostering Identity<br />

A post-mining landscape must have its own, new characteristics. The original<br />

landscape and <strong>the</strong> lost home cannot be reproduced. New developments must begin at<br />

meaningful locations, with <strong>the</strong> goal of promoting identification and shaping a new<br />

identity.<br />

4. Broadening <strong>the</strong> Planning Horizon<br />

The planning <strong>for</strong> a post-mining landscape must begin be<strong>for</strong>e mining lays claim to <strong>the</strong><br />

land. From <strong>the</strong> beginning, planning must represent goals <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> future design and<br />

development and must make possible new options <strong>for</strong> temporary use. Planning must<br />

accompany mining processes and react flexibly to changing framework conditions.<br />

5. Shaping <strong>the</strong> Process<br />

The process of redesign must be tangible. In<strong>for</strong>mation, staging of changes, and<br />

intermediate uses are important elements of <strong>the</strong> process that convey change and<br />

provide departure points <strong>for</strong> a change of identity.<br />

6. Allowing <strong>for</strong> Creativity and Innovation<br />

The development of new cultural landscapes requires a vanguard and creativity,<br />

exchange of insider and outsider perspectives, as well as open decision-making<br />

structures. The process must be organized in such a way as to facilitate innovative<br />

solutions and new pathways.<br />

Seite 6 von 8

7. Generating Pictures<br />

Pictures and outlines of a future development are important as eye-openers and<br />

vehicles <strong>for</strong> imagining <strong>the</strong> future. Even at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> conversion process<br />

events and constructed images are indispensable as landmarks to manifest <strong>the</strong> goals<br />

and perspectives of development.<br />

8. Ensuring Transparency<br />

The development of post-mining landscapes must be open and transparent. The triad<br />

— comprehensive participation by those who are affected, common decisionmaking,<br />

and implementation of planning with <strong>the</strong> participating actors — must be<br />

guaranteed in all phases of planning.<br />

9. Building <strong>the</strong> Organizational Structure<br />

The implementation of <strong>the</strong> planning goals must be secured by an organizational<br />

structure that is capable of acting and sufficiently equipped with funding and<br />

personnel. The organizational structure takes over <strong>the</strong> process management,<br />

establishes networks, and organizes funding and promotions. The requirement <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se functions is a binding legal framework that identifies planning levels, tasks and<br />

responsibilities.<br />

10. Taking Responsibility<br />

The polluter-pays principle applies to rehabilitation. The task of qualitative<br />

development that produces added value cannot be solved on <strong>the</strong> local level alone. It<br />

must be supported by entrepreneurial and higher-level public responsibility as well<br />

as by cooperation among local authorities and additional partners.<br />

The <strong>principles</strong> have been signed as a Lusatian-Charter in September 2010. This<br />

Charter serves as a self-obligation <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> stakeholders in <strong>the</strong> region to continue <strong>the</strong><br />

trans<strong>for</strong>mation process in a high quality in a laboratory, that’s unique in <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

3. Conclusions<br />

The project and <strong>principles</strong> of IBA demonstrate <strong>the</strong> opportunities inherent in <strong>the</strong><br />

rehabilitation of post-mining landscapes. It is necessary to have an overall concept,<br />

closely connected with <strong>the</strong> endogenous potentials of <strong>the</strong> region, in combination with<br />

an project oriented planning method. This planning method is typical <strong>for</strong> Germany.<br />

International starting points are heterogeneous and countries have differing<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> good redevelopment practice.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> differences, it is generally important to develop special strategies <strong>for</strong><br />

each region and to involve local people, not simply to enlist a variety of <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

cooperation, but also to shift a commitment to a civil society into <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>eground.<br />

This approach allows one to discover new ideas and potentials <strong>for</strong> regional<br />

development and to invent new regional governance structures.<br />

Overall <strong>the</strong> Principles <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Treatment of Post-Mining Landscapes do not represent<br />

a universal strategy, but an important basis <strong>for</strong> being able to identify and<br />

communicate <strong>the</strong> key qualitative demands made on redeveloping mining landscapes<br />

in all <strong>the</strong>ir dimensions in future. Their value lies in <strong>the</strong>ir claim to set standards that<br />

Seite 7 von 8

can be examined all over <strong>the</strong> world in <strong>the</strong> appropriate context and under different<br />

conditions and to serve as quality standards. And, of course, <strong>the</strong>y stand as a measure<br />

of quality <strong>for</strong> Lusatia as well: <strong>the</strong> process of post-mining redesign in <strong>the</strong> region does<br />

not end with <strong>the</strong> conclusion of IBA. For <strong>the</strong> IBA finale in 2010, <strong>the</strong> <strong>principles</strong> are to<br />

be developed fur<strong>the</strong>r as a »Lusatia Charter«, to be signed by those who are politically<br />

responsible and those running <strong>the</strong> mining operation – as a self-imposed obligation <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> future.<br />

5. References<br />

Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) Fürst-Pückler-Land (ed.) (2005) Trans<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

Landscapes. Recommendations based on three industrially disturbed landscapes in<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>. An Italian – Polish – German project “Restructuring cultural landscapes”<br />

REKULA (INTERREG III B Cadses). Großräschen.<br />

Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) Fürst-Pückler-Land (ed.) (2010a) Post-Mining<br />

Landscapes. Conference Documentation. Berlin: Jovis-Verlag.<br />

Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) Fürst-Pückler-Land (ed.) (2010b) New<br />

Landscape Lusatia. Catalog 2010. Berlin: Jovis-Verlag.<br />

Scholz, Brigitte (2009) Moving Land: International Building Exhibition Fürst-<br />

Pückler-Land 2000-2010 in Lower Lusatia. Conference „Landscape –Great Idea”<br />

(Proceedings), Vienna.<br />

Seite 8 von 8