Piotr KLEMENSIEWICZ « nuance » - Galerie Mons

Piotr KLEMENSIEWICZ « nuance » - Galerie Mons

Piotr KLEMENSIEWICZ « nuance » - Galerie Mons

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

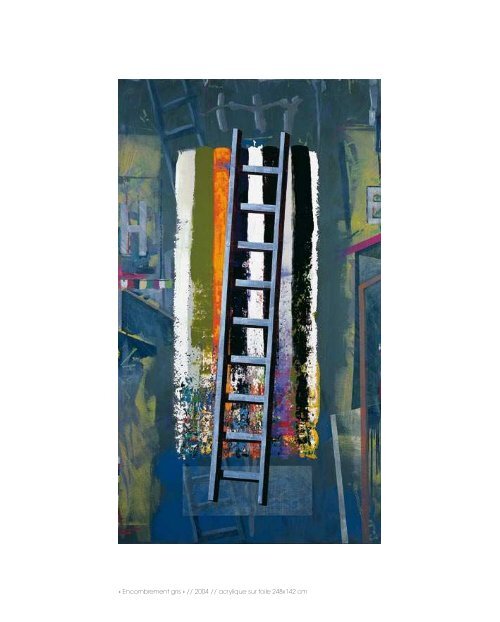

<strong>«</strong> Encombrement gris <strong>»</strong> // 2004 // acrylique sur toile 248x142 cm<br />

qu’une image ? faut-il qu’elle soit aussitôt lisible ? quelle portion du<br />

monde désigne-t-elle ? quels rapports entretient-elle avec son fond,<br />

son contexte, et les autres images ?<br />

Dans ces séries de paysages mentaux – au sens où la peinture de<br />

Magritte, par exemple, est une peinture mentale – j’aimerais maintenant<br />

m’attacher à celle intitulée les <strong>«</strong> Tas <strong>»</strong> (2000-03). Sur des fonds<br />

très variables d’un tableau à l’autre, mais où domine le bleu ou le<br />

violet, on voit se dresser dans la moitié inférieure la masse informe<br />

d’une sorte de <strong>«</strong> tas <strong>»</strong> plus ou moins géométrique, tandis que la<br />

moitié supérieure de la toile est occupée par un nuage-mensonge,<br />

aux contours, à l’étirement, à la texture variables. Le tas, ou le grand<br />

tas, c’est bien sûr et avant tout un <strong>«</strong> tas de peinture <strong>»</strong>, qu’on dirait<br />

peint à la manière d’un Philip Guston, avec un mépris hautain pour<br />

la <strong>«</strong> belle peinture <strong>»</strong> et le style <strong>«</strong> léché <strong>»</strong>. C’est, si l’on veut, la présence<br />

manifeste, concrète, brute et brutale, de la matérialité de la peinture.<br />

C’est ce tas qui encombrait les tables de peinture récupérées<br />

par Klemensiewicz, ce tas originel à partir duquel le peintre va créer<br />

ses lignes ou ses surfaces sur la toile ; et puis on ne peut s’empêcher<br />

de penser à ces autres tas de peinture alignés en haut des<br />

TotemtaboO avant que l’artiste ne prenne sa règle et n’en fasse<br />

des bandes raclées, arasant ainsi les reliefs, étalant la matière picturale<br />

en longs rectangles approximatifs. Mais dans la série dite des<br />

<strong>«</strong> Tas <strong>»</strong>, c’est aussi, et en même temps, une sorte de montagne sur<br />

fond de ciel, une montagne sans cesse reprise, dans ses variations,<br />

et le paysage de la Sainte-Victoire peint par Cézanne se profile<br />

assez vite à l’horizon imaginaire du tableau, d’autant plus que <strong>Piotr</strong><br />

Klemensiewicz a passé plusieurs années entre ce haut lieu de la peinture<br />

moderne et les cheminées verticales des usines de Gardanne.<br />

Au-dessus du pesant tas de peinture flotte un nuage cerné de<br />

noir, qui est peut-être la vue en coupe d’un objet indéfini ou bien,<br />

je l’ai dit, une carte, un monstre. À ces possibilités, j’ajouterai une<br />

autre interprétation, suggérée par la série antérieure intitulée<br />

<strong>«</strong> Planévations <strong>»</strong>, dont le titre inclut un plan et une élévation d’architecture<br />

: ce qui dans la série des <strong>«</strong> tas <strong>»</strong> apparaît comme un<br />

nuage pourrait être le plan au sol du tas inférieur, une hypothèse<br />

renforcée par le fait que la largeur du <strong>«</strong> nuage <strong>»</strong> supérieur est toujours<br />

à peu près identique à celle du tas inférieur. Comme pour les<br />

<strong>«</strong> Planévations <strong>»</strong>, on aurait donc deux vues du même objet et le<br />

tableau proposerait dans son espace propre et suturé deux représentations<br />

selon des plans perpendiculaires : en bas le tas comme<br />

paysage, en haut le tas comme plan.<br />

Néanmoins, cette forme cernée de noir est avant tout un nuagemensonge¸<br />

c’est-à-dire une idée, ou plutôt l’image d’une idée : le<br />

nuage est un animal pour Philostrate, mais il est redevenu un simple<br />

nuage pour le badaud convoqué par le philosophe ; pour nous il<br />

contient le fantôme d’Adam et celui de Eve ; pour le peintre il est<br />

l’image de <strong>«</strong> mon songe <strong>»</strong>, l’image de <strong>«</strong> mon idée <strong>»</strong> et, in fine, l’image<br />

picturale exemplaire de l’idée, l’image incarnée de la peinture<br />

comme idée, cosa mentale selon Léonard de Vinci. Alors, le sens<br />

ultime du tableau est à chercher du côté de la confrontation violente<br />

entre ces deux éléments incompatibles et pourtant réunis ici : en<br />

bas, la matière informe, excrémentielle, de la peinture brute ; en<br />

haut, l’entité aérienne, tantôt une trouée, une percée, tantôt un<br />

objet vaporeux, idéel, placé devant le fond d’un ciel parfois strié de<br />

coulures qui masquent un autre fond, lui-même incluant peut-être des<br />

images recouvertes… La profondeur est à la fois métaphysique<br />

– et l’on peut considérer tout l’œuvre peint de <strong>Piotr</strong> Klemensiewicz<br />

comme le déploiement de tels conflits sur une scène théâtrale<br />

proprement métaphysique – et très physique, matérielle, car elle<br />

s’inscrit dans le processus pictural d’effacements successifs, de<br />

disparitions programmées, où le fond, captant soudain l’attention<br />

plus que le motif, laisse entrevoir un double, voire un triple fond qui<br />

entraîne le regard vers une ou plusieurs dimensions cachées du<br />

tableau. À cet égard, l’artiste m’a confié s’être longtemps intéressé<br />

aux Annonciations de la Renaissance, et surtout à leur partie centrale,<br />

située entre l’ange Gabriel et la vierge Marie, cet espace intermédiaire<br />

désinvesti du rapport entre le messager divin et la mortelle<br />

élue, ce lieu du fond par excellence, ce no man’s land insidieusement<br />

investi par la pure peinture pour y manifester en douce et en<br />

toute clandestinité sa magnificence et son règne.<br />

Les Encombrements jouent d’inversions et de recouvrements<br />

similaires. Les motifs, abstraits ou reconnaissables, en général frag-<br />

painted in the manner of Philip Guston, with a haughty despise of<br />

the <strong>«</strong> beautiful painting <strong>»</strong> and of the great style. It is, in a way, the manifest<br />

presence, the brutal evidence of the materiality of painting. It<br />

is this heap which congested the tables of painting salvaged by Klemensiewicz,<br />

this original heap on the palette from which the painter<br />

is going to create his lines or his surfaces on the canvas ; and one<br />

cannot stop thinking of these other heaps of paint which form a line<br />

on the upper part of the TotemtaboO before the artist takes his ruler<br />

and transforms them into scraped strips, levelling the reliefs, spreading<br />

the pictural matter into long approximative rectangles. Even<br />

in the series called the <strong>«</strong> Heaps <strong>»</strong>, it is also and at the same time, a<br />

kind of mountain on a background of sky, repeated over and over<br />

with different variations, and the landscape of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire<br />

painted by Cézanne comes quickly to the mind, all the<br />

more so when you learn that <strong>Piotr</strong> Klemensiewicz has spent several<br />

years between this landmark of modern painting and the vertical<br />

chimneys of the Gardanne factories. Over this heavy heap of paint<br />

hovers a black-lined cloud, which could be the cross section of an<br />

indefinite object or, as I have said, a map, a monster. To these possibilities,<br />

I’d like to add another interpretation, suggested by a prior<br />

series untitled <strong>«</strong> Planévations <strong>»</strong>, a title which alludes to a plan and an<br />

architectural elevation : that which in the <strong>«</strong> Heap <strong>»</strong> series appears as<br />

a cloud could be the blueprint of the inferior heap, this hypothesis<br />

being reinforced by the fact that the width of the upper <strong>«</strong> cloud <strong>»</strong> is<br />

always approximately the same as that of the bottom heap. As for<br />

the <strong>«</strong> Planévations <strong>»</strong>, we would then have two views of the same object<br />

and the painting would propose in its own reconciliated space<br />

two representations of perpendicular plans : in the bottom the heap<br />

as landscape, in the upper part the heap as plan.<br />

However, this black-lined form is before all a cloud-lie, that is to say<br />

an idea, or rather, the image of an idea : the cloud is an animal for<br />

Philostratus, but it has become again a simple cloud for the ordinary<br />

man summoned by the philosopher ; and for us, it welcomes<br />

the ghosts of Adam and of Eve ; for the painter, it is the image of <strong>«</strong><br />

mon songe <strong>»</strong> (my dream), the image of <strong>«</strong> my idea <strong>»</strong> and, in fine, the<br />

pictural image of the Idea, the incarnate image of painting as Idea,<br />

cosa mentale according to Leonardo da Vinci. Then the ultimate<br />

meaning of the painting must be sought in the violent confrontation<br />

between these two incompatible but here reunited elements :<br />

in the bottom, the informal matter, the excrement of brute paint ; in<br />

the upper part, the airy entity, now a hole, a breakthrough, then a<br />

vaporous object, an ideal, placed in front of a sky sometimes streaked<br />

with drippings that dissimulate another background, which itself<br />

contains maybe other overlapped images… The deepness is at the<br />

same time metaphysical - and all the painted work of Klemensiewicz<br />

can be viewed as the display of such conflicts on a theatrical scene<br />

which is also metaphysical –, and very physical, material, since it occurs<br />

in the pictural process of successive erasings, of programmed<br />

disappearances, where the background, suddenly getting much<br />

more attention than the motif, allows the perception of a second<br />

or of a third background, which leads the eye towards one or several<br />

hidden dimensions of the painting. On this matter, the artist<br />

has told me that for a long time he’s been interested in the Renaissance<br />

Annunciations, and mostly in their central part, between the<br />

angel Gabriel and the virgin Mary, this intermediary surface which<br />

seemingly has no importance in the fundamental religious relation<br />

between the godly messenger and the chosen woman, this elective<br />

place of the background, this no man’s land stealthily stolen by<br />

pure painting, where it can manifest and smuggle its munificence<br />

and its reign.<br />

The Encombrements show similar inversions and overlappings. The<br />

motifs, abstract or recognizable, generally fragmentary, are cast<br />

on the periphery of the painting, which gets paradoxically <strong>«</strong> disencumbered<br />

<strong>»</strong>. The central zone is then occupied by an absence, an<br />

emptiness, where the painting probably gives its full scale, where it<br />

vibrates most, and where it reveals itself absolutely as painting. The<br />

background becomes the raison d’être of the painting, in its interaction<br />

with all these centrifugal objects which disencumber it and<br />

flee towards the margins in order to offer it to the onlooker – the<br />

truncated K, a piece of a house, many fragments of small paintings<br />

in the painting, a few geometrical structures reminding us of the<br />

wood pieces of a stretcher, sometimes at the bottom of the can-