Booklet - Österreichisches Filmmuseum

Booklet - Österreichisches Filmmuseum

Booklet - Österreichisches Filmmuseum

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 1<br />

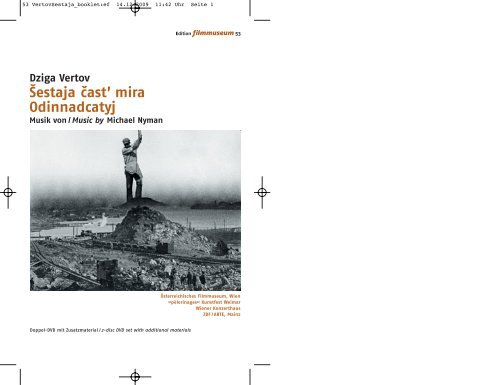

Dziga Vertov<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira<br />

Odinnadcatyj<br />

Musik von /Music by Michael Nyman<br />

Doppel-DVD mit Zusatzmaterial /2-disc DVD set with additional materials<br />

53<br />

<strong>Österreichisches</strong> <strong>Filmmuseum</strong>, Wien<br />

»pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar<br />

Wiener Konzerthaus<br />

ZDF / ARTE, Mainz

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 2<br />

<strong>Filmmuseum</strong> ist: Forschung & Vermittlung. In diesem Sinne versteht sich diese DVD-Edition<br />

als Verlängerung des Kinos (dem Ort des Films) und des Museums (als Ort der Bewahrung<br />

und Ausstellung) in die Bereiche der künstlerischen und wissenschaftlichen Exploration.<br />

Mit dieser Veröffentlichung wollen wir zwei rare Meisterwerke Dziga Vertovs einer neuen<br />

Öffentlichkeit zugänglich machen; zugleich präsentiert die DVD Ergebnisse eines inter -<br />

disziplinären Forschungsprojekts (Digital Formalism. The Vienna Vertov Collection), in<br />

welchem die Universität Wien, die Technische Universität Wien und das <strong>Filmmuseum</strong><br />

Vertovs Werk einer erneuten Untersuchung unterzogen haben. Für diese Zusammenarbeit<br />

gilt unser Dank den wissenschaftlichen Partnern Klemens Gruber, Andrea B. Braidt und<br />

Christian Breiteneder.<br />

Ein Glücksfall ist die Kooperation mit dem Komponisten Michael Nyman, dessen<br />

Enthusiasmus für Vertovs Werk sich in gleich zwei neuen Soundtracks manifestiert. Seine<br />

Neugier und die Initiative von Annette Gentz, Matthias Schneider und Barbara Wurm gaben<br />

den Anstoß für diese Zusammenarbeit.<br />

Doch ohne Geld keine Musik (und keine Forschung) – so gilt unser Dank nicht zuletzt den<br />

Förderern dieses Projekts. Dem WWTF als Ermöglicher des Forschungsprojekts; »pèlerinages«<br />

Kunstfest Weimar (Nike Wagner, Ulrich Hauschild) für den Kompositions auftrag der Musik<br />

zu Odinnadcatyj; der Wiener Konzerthausgesellschaft für den Kom positions auftrag zu<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira; und der unermüdlichen Nina Goslar (ZDF / ARTE) für ihren Einsatz für<br />

den Stummfilm in der deutschsprachigen Fernsehlandschaft.<br />

<strong>Filmmuseum</strong> is: research and education. In this sense, we can consider this DVD an<br />

extension of the cinema (the figurative “home” to films) and the museum (as home to<br />

the acts of conservation and exhibition) in the realm of artistic and scientific exploration.<br />

With this DVD publication, we hope to make two rare masterpieces by Dziga Vertov<br />

accessible to a new audience – and, at the same time, present the results of an inter -<br />

disciplinary research project (Digital Formalism. The Vienna Vertov Collection), in which the<br />

University of Vienna, the Vienna University of Technology and the Austrian Film Museum<br />

have been reappraising Vertov’s work. Our thanks go to our project partners Klemens<br />

Gruber, Andrea B. Braidt and Christian Breiteneder.<br />

The co-operation with composer Michael Nyman, whose enthusiasm for Vertov is<br />

manifest in his two new soundtracks, has been a stroke of luck. It was his curiosity –<br />

and the initiatives of Annette Gentz, Matthias Schneider and Barbara Wurm – that gave<br />

impulse to this collaboration.<br />

Of course, without money there can be no music (and no research) – and so, not least<br />

of all, our thanks go to the project sponsors: to the WWTF for enabling the research project;<br />

to »pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar (Nike Wagner, Ulrich Hauschild) for commissioning the<br />

new soundtrack to Odinnadcatyj; to Vienna Konzerthaus for co-commissioning the music<br />

for Šestaja čast’ mira; and to Nina Goslar (ZDF/ARTE) for her tireless commitment to bringing<br />

silent films to German-speaking television audiences.<br />

Alexander Horwath Šestaja čast’ mira, Odinnadcatyj

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 4<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira (1926) / Odinnadcatyj (1928)<br />

Barbara Wurm<br />

„Ein Sechstel der Erde ist mehr als ein Film, mehr als wir unter der Bezeichnung ‚Film‘<br />

zu verstehen gewöhnt sind. Teils Chronik, teils Komödie, teils künstlerischer Filmreißer.<br />

Ein Sechstel der Erde geht irgendwie über die Grenze dieser Begriffsbestimmung hinaus –<br />

das ist schon die nächste Stufe der Auffassung über Kinematografie. […] Unsere Losung ist:<br />

Alle Bürger der UdSSR von 10 bis 100 Jahren müssen diesen Film sehen. Am 10. Jahrestag des<br />

Oktobers darf es auch nicht einen Tungusen geben, der Ein Sechstel der Erde nicht gesehen<br />

hat.“ 1<br />

Dziga Vertov hatte erstmals in seiner Karriere allen Grund zur Begeisterung. Šestaja čast’<br />

mira wurde hymnisch gefeiert, eine veritable Medienkampagne war im Gang. Auch wenn<br />

später kritische Stimmen zu hören waren – Šestaja čast’ mira, im Untertitel mal trocken<br />

„Kinoglaz-Wettlauf durch die UdSSR. Export und Import von Gostorg der UdSSR“, mal<br />

euphorisch „revolutionär-pathetischer Hit“ genannt, das war zunächst: das erste, gleich -<br />

zeitig ultimative „Poem der Fakten“; eine den Körper durchdringende rhythmische Melodie,<br />

eine „Filmsymphonie mit kontrapunktischer Struktur, wiederkehrenden Themen, Crescendos<br />

und Diminuendos, Prestos und Lentos“; ein Film, der „100% UNSERER ist, SOWJETISCH“; eine<br />

Demonstration des „filmischen Phrasenbauens“; ein „Poem über die Welt – und ihre zwei<br />

gigantischen miteinander konkurrierenden Blöcke“; die „einzige Waffe“ im Kampf gegen<br />

die immanenten Kunstgesetze; der erste emanzipatorische Film „über die Neue Frau“; nicht<br />

mehr „Geburtsschrei“ oder „erste Schritte“, sondern „die ersten Worte des Kindes“ namens<br />

Sowjetkino.<br />

Der Film war auch der endgültige Durchbruch für Dziga Vertov und seine Kinoki. Endlich<br />

schien sein Konzept aufzugehen, dem Nicht-Spielfilm jenes Filmische (zurück) zu geben, das<br />

ihm aufgrund seines starken Realitätsbezugs grundsätzlich abgesprochen worden war. Die<br />

Exkursion des Kino-Auges bis an die Grenzen des Sowjetreiches, der genuine Blick auf die<br />

Kulturen der Ethnien und der Produktion, die Grundlagendarstellung der ökonomischen<br />

Prinzipien von Gostorg, der Staatlichen Handelsorganisation, ebenso wie der Blick ‚hinüber’<br />

auf die Lebensweise und Gedankenwelt der NEP-Männer und Kolonialisten, auf Foxtrottund<br />

Leuchtreklamenwelt, auf den Kapitalismus „am Rande seines historischen Untergangs“<br />

eben, wie es in einem Zwischentitel heißt – dieser so lokal geschilderte globale Kampf<br />

der Welt des OKTOBERs gegen die Welt des KAPITALs wäre ohne die strenge Form, ohne<br />

die Rhythmik und Dynamik der Zwischentitel-Bild-Montage völlig unbedeutend geblieben.<br />

Vertov rüttelt mit Šestaja čast’ mira – das wird besonders bei den vielen ethnographischen<br />

Szenen deutlich – an herkömmlichen Genre- und Gattungsdefinitionen. Jeder seiner<br />

Filme ist eine Revolution, diesmal in Sachen Film-Gattung-Form, wie auch die eingangs<br />

zitierte Passage belegt. Erstmals traten bei Vertov, dem Anti-Kunst-Filmer, die künstlerischen<br />

Verfahren so dominant hervor, dass sich sogar der bis dahin kritische Viktor Šklovskij<br />

1 Dziga Vertov in einem Interview über Šestaja čast’ mira für die Filmzeitung „Kino“ vom 17. 8. 1926<br />

(dt. in: Sowjetischer Dokumentarfilm, hg. v. Wolfgang Klaue / Manfred Lichtenstein, Berlin 1976, S. 188).<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira<br />

(ausgerechnet von einem Auftragsfilm Vertovs) zu seinem neuen Forschungsinteresse innerhalb<br />

der russisch-formalistischen Filmtheorie inspirieren ließ. Šestaja čast’ mira war für<br />

ihn „Kino der Poesie“ mit Parallelismus-Formel und Triolett-Struktur. „Es gibt“, schreibt er<br />

„ein Kino der Prosa und ein Kino der Poesie – und dies ist eine grundlegende Einteilung<br />

der Gattungen. Sie unterscheiden sich nicht durch den Rhythmus […] allein, sondern durch<br />

die Vorherrschaft technisch-formaler Momente (im poetischen Film) über semantische.<br />

Die formalen Momente ersetzen hierbei die semantischen, indem sie die Komposition<br />

zur Lösung bringen. Der sujetlose Film ist der vershafte Film.“ Vertov markierte innerhalb<br />

der umfassenden Gattungstheorie Adrian Piotrovskijs, die ebenfalls im formalistischen<br />

Sammelband Poetika kino erschienenen war, sogar den Paradigmenwechsel zum „sujetlosen<br />

Film“: „Die Gattung von Šestaja čast’ mira ist völlig frei von Fabelverkettungen, völlig frei<br />

auch von der Illusion einer voranschreitenden Bewegung der Zeit. Menschen und Dinge,<br />

Menschen und Natur werden hier als ihren Zweck in sich selbst tragende semantische<br />

Größen gezeigt. Ihre Aufeinanderfolge gehorcht allein den sich selbst genügenden Gesetzen<br />

der Montage, insbesondere den Gesetzen der rhythmischen Komposition. Dieses Moment,<br />

das Moment des Rhythmus, ist sicherlich in jeder Filmgattung vorhanden, jedoch im Aufbau<br />

von nicht-fabelgebundenen Filmen ist seine Bedeutung ganz außerordentlich. Es ist die<br />

rhythmisch ausgewogene Montage, welche Šestaja čast’ mira von der altherbekannten,<br />

aber außerhalb der künstlerischen Filmgattungen stehenden Kategorie der Wochenschau<br />

unterscheidet. Für die Filme der Kinoki ist der Rhythmus ein ebenso grundlegender<br />

Kompositionsfaktor wie die Steigerung der Tricks für den Abenteuerfilm und der Wechsel<br />

von Großaufnahmen für die lyrische Idylle.“<br />

Ob Hymne auf den Oktober oder Pionier der reinen Filmform, Šestaja čast’ mira galt als<br />

Film der Superlative – und das auch finanziell: nach einem Riesenkrach wurde Vertov von

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 6<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira Odinnadcatyj<br />

Sovkino entlassen. Die Debatten eskalierten und zogen sich bis tief in das Jahr 1927. Für die<br />

einen war Vertov der einzige Sowjetfilmer von internationalem Format, filmhistorisch längst<br />

neben Griffith, Chaplin und Gance einzuordnen, während in den Polemiken der anderen<br />

die bis heute aktuellen Grundsatzdebatten des Dokumentarischen geführt wurden. Mit<br />

Odinnadcatyj, dem Jubiläumsfilm im elften Jahr nach der Oktoberrevolution, realisiert von<br />

der VUFKU in Kiev, trieb Vertov das Spiel weiter – nicht mehr und nicht weniger als die<br />

„Zusammenfassung der neuen Visualität“ sollte entstehen. Obwohl der Establishing Shot<br />

in beiden Filmen jeweils ein über die Landschaft kreisendes Flugzeug zeigt – Index für die<br />

schwindelnde Höhe, von der aus die Beobachtung des Lebens, das „Ich-Sehe“ der Kamera<br />

einsetzt – entwickelt sich Odinnadcatyj formal in eine gänzlich andere Richtung. Hier steht<br />

nicht mehr die rhythmische Zwischentitel-Bild-Montage von mehrheitlich statischen Bild -<br />

kompositionen im Vordergrund, sondern ein fast lyrisches, dynamisches Fließen bewegter<br />

Einstellungen, die zwar teilweise ikonischen Status erlangen (wie die auf den Wasser -<br />

massenguss projizierte Lenin-Büste), oft aber auf nichts anderes als pure Visualität von<br />

Bewegung verweisen (die Anzahl der Zwischentitel ist drastisch reduziert). Spektakuläre<br />

Fotografie- und Überblendungsexperimente erzeugen einen „geschichteten Raum“.<br />

Auf diese Weise wird, ähnlich wie in Šestaja čast’ mira, der stilistische Grundtenor des<br />

Films zu seinem Thema: Waren es dort die Topoi der Verschaltung und Vernetzung auf allen<br />

Ebenen, so steht die Hymne auf die Industrialisierung der Ukrainischen SSR am Beispiel<br />

der Wasserkraftwerke an Dnepr und Volchov für die Überlagerung, Überschichtung und<br />

Übertragung als den Grundelementen des Kreislaufs der Energie. Je nach Fokus entfaltet<br />

sich – ausgehend von der einen Idee der „Erhebung der Elektrokraft“ – eine fundamentale<br />

ökonomische Archäologie der Menschheitsgeschichte oder aber eine radikalformalistische<br />

Studie von „ihren Zweck in sich selbst tragenden semantischen Größen“. Form und Inhalt<br />

sind untrennbar. Odinnadcatyj stand naturgemäß unter Formalismus-Verdacht, gerade<br />

deshalb aber inspiriert der Film bis heute zu filmanalytischer Kreativität.<br />

Noch vor dem absoluten Meta-Kino des Čelovek s kinoapparatom (Der Mann mit der<br />

Kamera) sorgten die selbstreflexiven Film-im-Film-Szenen in Šestaja čast’ mira für Aufruhr:<br />

Die Zuschauer konnten sich hier ‚selbst‘ auf der Leinwand erblicken und wurden damit<br />

aktiver Bestandteil des Films, was alle bisherigen Vorstellungen von einem partizipatorischen<br />

Kino übertraf. Ob die zeitgenössische Rezeption flächendeckend war, so wie Vertov<br />

das einforderte, sei dahingestellt. Odinnadcatyj sahen in den ersten drei Tagen wohl 10.000<br />

Menschen. Heute muss dagegen eine in der Filmgeschichte einzigartige Diskrepanz zwischen<br />

dem Aha-Effekt eines Regie-Namens und der tatsächlichen Unzugänglichkeit des Œuvres<br />

konstatiert werden. Wer Vertov schrieb, meinte meist nur Čelovek s kinoapparatom, vielleicht<br />

noch Kinoglaz oder Tri pesni o Lenine. Die vorliegende Doppel-DVD ist also schon<br />

allein deshalb eine Sensation, weil sie jene zwei unmittelbar nacheinander (und vor dem<br />

chef d’œuvre) entstandenen Werke zusammen bringt, die von der Hochphase der avant gardistischen<br />

20er Jahre und damit der rigorosesten Experimentierphase Vertovs geprägt sind.<br />

Dazu kommen aber noch zwei editorische Specials: einerseits die Tatsache, dass<br />

Starkomponist Michael Nyman bei einer Tasse Tee am Londoner Kamin einverstanden war,<br />

sich an beide filmischen Rhythmus-Extreme aus musikalischer Perspektive heranzuwagen;<br />

andererseits die wissenschaftlich-archivarische Edition durch das Österreichische <strong>Filmmuseum</strong><br />

im Rahmen des Digital Formalism-Projekts. Odinnadcatyj, der bis dato wohl unbekannteste<br />

aller Vertov-Filme und ein Paradefall für die Schwierigkeiten der Überlieferung, erhält hier<br />

eine Maximalaufbereitung. Mit dem „Fund“ des Endstücks von Odinnadcatyj, einem Glücks -<br />

fall der filmanalytischen Forschung, wird Geschichte geschrieben. Vertov hätte gesagt:<br />

„Alle Bürger von 10 bis 100 Jahren müssen diesen Film sehen.“

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 8<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira (1926) / Odinnadcatyj (1928)<br />

Barbara Wurm<br />

“A Sixth Part of the World is more than a film, than what we have got used to under -<br />

standing by the word ‘film’. Whether it is a newsreel, a comedy, an artistic hit-film,<br />

A Sixth Part of the World is somewhere beyond the boundaries of these definitions; it is<br />

already the next stage after the concept of ‘cinema’ itself. […] Our slogan is: All citizens<br />

of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics from 10 to 100 years old must see this work.<br />

By the tenth anniversary of October there must not be a single Tungus who has not seen<br />

A Sixth Part of the World.” 1<br />

For the first time in his career, Dziga Vertov had every reason to be enthusiastic. Šestaja<br />

čast’ mira had been eulogistically praised; a veritable media campaign was in full swing.<br />

Even if critical voices were later to be heard, Šestaja čast’ mira – sometimes dryly referred<br />

to as (in the words of its own sub-title) a “Kino-Eye Race around the USSR: Export and<br />

Import by the State Trading Organization of the USSR” and sometimes euphorically as a<br />

“revolutionary-emotional hit” – met with descriptions such as: the first and ultimate<br />

“poem of facts”; a “cinema symphony with contrapuntal structure, recurring themes,<br />

crescendos and diminuendos, prestos and lentos”, a rhythmic melody pervading the<br />

body; a film that was “100 percent ours, Soviet!”; a demonstration of “cinematic phrasemaking”;<br />

a “poem about the Earth, about its two gigantic struggling blocks”; “our only<br />

weapon against the ‘immanent laws of art’”; the first emancipatory film “featuring the<br />

New Woman”; not “the first cry of the child” or “first steps”, but “the first words of a<br />

child” named Soviet cinema.<br />

The film was also the final breakthrough for Dziga Vertov and his Kinoki. At long last,<br />

his concept seemed to work out: to give (back) the filmic to non-fiction film (which,<br />

owing to its close relationship with reality, had been denied it as a matter of principle).<br />

The Kino-Eye’s excursion to the very borders of the Soviet realm, its genuine view of ethnic<br />

and production cultures, its key depiction of the economic principles of Gostorg, the State<br />

trade organisation, as well as its glance towards the lives and ideas of NEP men and colonialists,<br />

the world of the foxtrot and luminous advertising, and finally at capitalism “on<br />

the verge of its historical collapse”, as one of the intertitles puts it – this global (but<br />

locally anchored) struggle between the world of OCTOBER and the world of CAPITAL would<br />

not have had any effect if it weren’t for its strict form and the rhythm and dynamics of<br />

its montage of images and intertitles.<br />

As becomes particularly apparent from the film’s many ethnographic scenes, Vertov<br />

shook the traditional definitions of genre. As the opening quotation also suggests, each<br />

of his films is a revolution, in this case concerning the relation of film, genre, and form.<br />

For the first time in Vertov’s “anti-art” oeuvre, artistic devices prevailed; to the point<br />

where even the previously critical Viktor Shklovsky was inspired (by, of all things, Vertov<br />

1 Dziga Vertov in an interview on Šestaja čast’ mira for the newspaper Kino, August, 17, 1926,<br />

In: Lines of Resistance. Dziga Vertov and the Twenties. Ed. by Yuri Tsivian. Sacile/Pordenone 2004, p. 182–84).<br />

Odinnadcatyj<br />

and a “commissioned” film) to shift his research interests within Russian formalist film<br />

theory. For Shklovsky, Šestaja čast’ mira was “poetic cinema” with a parallelism formula<br />

and a triolet structure: “In cinema, both prose and poetry exist, and this is the basic<br />

division between the genres: they are distinguished from one another not by rhythm […]<br />

alone, but by the prevalence in poetic cinema of technical and formal over semantic<br />

features, where formal features displace the semantic and resolve the composition. Plotless<br />

cinema is ‘verse’ cinema.” In Adrian Piotrovsky’s broad genre theory, which had likewise<br />

appeared in the formalist anthology Poetika kino, Vertov even represented the changing<br />

paradigms of the “plotless film”: “The genre of A Sixth Part of the World is completely free<br />

from the convention of narrative linkage and from the illusion of a linear progression of<br />

time. People and objects, people and nature, are shown here as self-contained signifying<br />

units. Their alternation is subject only to the self-contained laws of montage, specifically to<br />

the laws of rhythmic composition. The function of rhythm can hardly be disputed in regard<br />

to any cine-genre, but in the construction of plotless films it acquires extreme importance.<br />

A montage regulated by rhythm is the feature that marks the newly invented genre of<br />

The Sixth Part of the Earth as an aesthetic genre, distinguishing it from the established<br />

category of the newsreel, which lies outside the field of artistic cine-genres. Rhythm is the<br />

basic compositional factor for the genre invented by the Kinoki, just as the build-up of<br />

stunts is for the adventure film, and the alternative of close-ups is for the lyrical idyll.”<br />

Whether as a hymn to the October revolution or as a pioneering example of pure film<br />

form, Šestaja čast’ mira was considered a film of superlatives – including financial super -<br />

latives (Vertov had been dismissed by Sovkino following a massive dispute). The debates<br />

escalated and dragged on well into 1927. For one side, Vertov was the only “international”<br />

Soviet filmmaker who would rank alongside Griffith, Chaplin and Gance in film history. For

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 10<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira Odinnadcatyj<br />

the other, he was a central and “problematic” figure in the polemical debate (still raging<br />

today) about the basic principles of documentary film. With Odinnadcatyj, the “celebration<br />

film” realised by the VUFKU in Kiev in the 11 th year following the October revolution, Vertov<br />

took the game even further – aiming at nothing less than the “summary film” of a “new<br />

visuality”. Although the establishing shots in both films show a plane circling over the earth<br />

– an index of the dizzying heights from which the “I-Can-See” of the camera establishes<br />

its observation of life –, Odinnadcatyj unfolds in a quite different direction, at least on the<br />

formal level. Here, the rhythmic montage of (mostly) static compositions is replaced by an<br />

almost lyrical, dynamic flow of moving shots. In several cases, these images attain iconic<br />

status (as, for example, the bust of Lenin projected upon the gushing water), but often<br />

they refer simply to the pure visuality of movement (the number of intertitles is drastically<br />

reduced here). Spectacular photography and experimental super-impositions constitute a<br />

“layered space”. Thus, in a manner similar to Šestaja čast’ mira, the stylistic essence of the<br />

film reaches its point: In the earlier film, it had been the topoi of wiring and networking<br />

on all levels. In Odinnadcatyj, the anthem for the industrialisation of the Ukrainian SSR as<br />

exemplified by the hydroelectric stations on the Dnepr and Volchov rivers, suggests that<br />

superimposition, overlap and transmission are the basic elements in the circular flow of<br />

energy. From a single idea – the “rise of electric force” – two potential readings develop:<br />

an in-depth economic archaeology of human history or a radical formalist study of “selfcontained<br />

signifying units”. Form and content are inseparable. Naturally, Odinnadcatyj<br />

was suspected of formalism. For this very reason, however, the film still inspires creativity<br />

in film analysis today.<br />

Three years before the absolute “Meta-Cinema” of Čelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with<br />

a Movie Camera), the self-reflexive film-within-a-film scenes in Šestaja čast’ mira created<br />

a stir: Audience members could catch a glimpse of their very selves on-screen and, as a<br />

result, became an active component of the film, surpassing all previous conceptions of<br />

a participatory cinema. The issue of whether contemporary reception of the film was<br />

truly nationwide, as Vertov claimed, remains a subject for further research. But apparently<br />

10,000 people saw Odinnadcatyj during its first three days of release. In contrast, we are<br />

today faced with one of film history’s unique discrepancies – between the “Eureka” effect<br />

produced by a director’s name and the actual inaccessibility of his oeuvre. Those who<br />

say “Vertov” mostly mean Čelovek s kinoapparatom; perhaps also Kinoglaz or Tri pesni o<br />

Lenine. This double-disc DVD can, therefore, be seen as something of a sensation simply<br />

for bringing together two of his major works, produced back-to-back at the creative<br />

pinnacle of the 1920s avant-garde movement – Vertov’s most rigorously experimental<br />

phase. In addition, however, it offers two curatorial “specials”: the fact that composer<br />

Michael Nyman accepted, over a cup of tea by his London fireside, the challenge of giving<br />

a musical perspective to these rhythmic extremes of cinema; and the extensive scholarly<br />

“bonus” materials laid out here by the Austrian Film Museum, all resulting from the<br />

Digital Formalism research project in Vienna. Odinnadcatyj – perhaps the least known<br />

of Vertov’s features and a textbook example of the difficulties of historical transmission –<br />

receives extensive treatment. The discovery of its “lost finale” – a stroke of luck in film<br />

analysis and archival research – is a historical moment. As Vertov himself would have said:<br />

“All citizens from 10 to 100 years old must see this work.”

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 12<br />

Der Schatten eines Zweifels<br />

Odinnadcatyj und Im Schatten der Maschine<br />

Die „Affäre Blum“<br />

Als Dziga Vertov im Mai 1929 zum ersten Mal ins Ausland reist und auf seiner Vortragstournee<br />

vor deutschen Filmklubs unter anderem Ausschnitte seines Films Odinnadcatyj<br />

zeigt, bezichtigt man ihn in der Presse des Plagiats. Er hätte Aufnahmen aus dem deutschen<br />

Film Im Schatten der Maschine von Albrecht Viktor Blum und Leo Lania ungekennzeichnet<br />

in seinen Film Odinnadcatyj übernommen. Vertov ist fassungslos, denn tatsächlich verhält<br />

es sich genau umgekehrt: Sein bisher in Deutschland noch nicht gezeigter Film war von<br />

Blum und Lania für ihre Kompilation ausgeplündert worden.<br />

Im Schatten der Maschine war als ein „Musterfilm“ für den kommunistischen Volksfilm<br />

verband (VFV) als reine Kompilation angelegt und ist als erste Eigenproduktion des<br />

Volks filmverbandes wohl extra für diesen Zweck, unter großem Zeitdruck produziert worden.<br />

Blum: „Er wird aus Ausschnitten von zum Teil noch nicht vorgeführten ukrainischen Filmen<br />

zusammengesetzt sein (…) Auch einige amerikanische Filme sind mitverwandt worden.<br />

Um ein möglichst eindringliches Material zu bekommen, wurden etwa 50–60 Filme<br />

durchgesehen.“<br />

Interessant ist daran, dass Blum die im Kontext einer Begeisterung für die Technik<br />

gedrehten sowjetischen Bilder durch die neue Kontextualisierung und durch Umarbeitung<br />

der Zwischentitel in eine Technikkritik umdreht. Seine Intention beschreibt er wie folgt:<br />

„Die Maschine, vom Menschen erfunden zu dem Zweck, dass sie dem Menschen dient,<br />

wird mehr und mehr zum Beherrscher des Erfinders. Ja, im Endresultat wird der Mensch<br />

nur noch ein Handlanger, ein Sklave der Maschine selbst.“ 1 Die technikfeindliche<br />

Ausrichtung ist dem Einsatz des Films unter kapitalistischen Verhältnissen geschuldet,<br />

in denen das Industrieproletariat Technik allein als Rationalisierung und Taylorisierung<br />

erfährt; Blum zeigt u.a. Großaufnahmen von durch Maschinen verstümmelten Händen<br />

und Fingern. 2 Die Autoren hatten laut Blum ausdrücklich die Zielgruppe der Industrie -<br />

arbeiterInnen im Auge, insbesondere die Gewerkschaften.<br />

Blum hatte laut eigenen Angaben seine Kompilation im Wesentlichen aus dem fünften<br />

(Halb-)Akt von Aleksandr Dovženkos Zvenigora (SU 1928) und dem letzten Akt von Dziga<br />

Vertovs Odinnadcatyj zusammengestellt. Aus Vertovs Film habe er 86 m (= 3’50’’ bei 20<br />

Bilder/Sekunde) „nur mit ganz geringfügigen Änderungen als fertige Montage komplexe“<br />

übernommen, da diese Partien, so Blum, „den auszudrückenden Gedanken schon be -<br />

inhalteten“. Unerwähnt bleiben hier seine Eingriffe in das Material, z. B. mit Hilfe der<br />

neuen Zwischentitel.<br />

Vertov sieht sich zu Richtigstellungen in der deutschen Presse genötigt, obwohl das<br />

sowjetische Filmkontor die Affäre aus politischen Gründen unter dem Teppich kehren<br />

1 Albrecht Viktor Blum: „Protokoll vom 5. 8. 1929 über die Angelegenheit Blum/Vertov“, in: Thomas Tode /<br />

Alexandra Gramatke (Hg.): Dziga Vertov – Tagebücher / Arbeitshefte, Konstanz: UVK 2000, S. 25.<br />

2 Vermutlich eine Anregung für seine weitere Kompilation Hände (D 1928/29).<br />

Odinnadcatyj, Čelovek s kinoapparatom<br />

möchte. Vertov betrachtet die Angelegenheit ganz im Sinne des bürgerlichen Gesetzbuchs<br />

als einen Fall von Diebstahl geistigen Eigentums. Blum erklärt, er sei von seinem Auftrag -<br />

geber Weltfilm daran gehindert worden, die Quellen anzugeben, da er aufgrund der<br />

Kontingentbestimmungen „in dem als deutsche Produktion eingereichten Kurzfilm<br />

keinen Meter ausländisches Material verwenden durfte“.<br />

Thomas Tode<br />

Auf den Spuren des Materials<br />

Wie bei vielen sowjetischen Filmen ist auch bei Odinnadcatyj die Überlieferungslage unklar.<br />

Die Originallänge von Odinnadcatyj betrug laut offiziellem „Repertuarnyj bulletin“ und<br />

„Repertuarnyj ukazatel’“ 1600 Meter (nach anderen Quellen: 1428 Meter). Die Länge der im<br />

Gosfilmofond und im Österreichischen <strong>Filmmuseum</strong> erhaltenen Kopie beträgt 1229,1 Meter.<br />

Für diesen großen Unterschied in der Länge gibt es keine definitiven Erklärungen, es<br />

konnten bislang weder in der russischen Presse der 1920er Jahre, noch im Vertov-Archiv<br />

in Moskau Aufzeichnungen darüber gefunden werden, ob eine andere Fassung des Films<br />

hergestellt wurde. Ein Vergleich der Zwischentitel in der vorhandenen Filmkopie mit einer<br />

Zwischentitelliste von 1928, die in der Vertov-Sammlung des ÖFM vorhanden ist, zeigt einige<br />

interessante Abweichungen. In der Filmkopie fehlen demzufolge insgesamt sieben Titel, die<br />

sich ursprünglich an Anfang und Ende eines Halbaktes befanden. Details dazu finden sich<br />

im ROM-Bereich der DVD.<br />

In jedem Fall erklärt sich die geringere Metrage der erhaltenen Kopie von Odinnadcatyj<br />

nicht aus Eingriffen der Zensur; denn schon in der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 1931 wurde<br />

der Film aus dem Verleih genommen, deshalb bestand keinerlei Notwendigkeit, eine neu<br />

montierte Version herzustellen. Es scheint plausibel, dass VUFKU das Material des Films für<br />

verschiedene Zwecke „recycelt“ hat. Einen Teil des Original-Negativs konnte der russische<br />

Regisseur Abram Room verwenden, als er in den Jahren 1929-1930 seinen Montagefilm<br />

Pjatiletka herstellte. Die Hoffnung, hierdurch verlorene Sequenzen aus Vertovs Film rekonstruieren<br />

zu können, wird leider enttäuscht – Pjatiletka gilt als verloren. Es kann auch nicht<br />

ausgeschlossen werden, dass Vertov selbst Teile des Negativs in der Montage von Čelovek<br />

s kinoapparatom (Der Mann mit der Kamera) (den er kurz nach der Uraufführung von<br />

Odinnadcatyj fertigstellte), ˙Entuziazm (Enthusiasmus) und Tri pesni o Lenine (Drei Lieder<br />

über Lenin) wiederverwendete. In der berühmten „Schneideraum-Sequenz“ von Čelovek<br />

s kinoapparatom erscheinen zahlreiche Dubletten und „Alternativen“ zu aus Odinnadcatyj<br />

bekannten Motiven und Sujets; in Tri pesni o Lenine findet sich zum Beispiel eine lange,<br />

alternierend montierte Sequenz von Aufnahmen vom Bau des Dnjeprostroj-Kraftwerks, die<br />

große Ähnlichkeit zu den von Vertov in einem Autographen (V 72 in der Wiener Vertov-<br />

Sammlung) festgehaltenen Sujets für Odinnadcatyj aufweisen.

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 14<br />

Im Projekt Digital Formalism wurden zum ersten Mal systematisch und ausführlich<br />

die widersprüchlichen Literaturangaben über die ursprüngliche Länge des Films überprüft.<br />

Dazu wurden zunächst alle Schnitte von Odinnadcatyj manuell annotiert (insgesamt<br />

654 Einstellungen) und diese anschließend mittels automatischer Shot-Erkennung mit<br />

Im Schatten der Maschine verglichen. Insgesamt konnten 30 Einstellungen in Im Schatten<br />

der Maschine als aus Odinnadcatyj stammend identifiziert werden, die bis auf eine alle<br />

aus dem letzten Akt stammen. Wir können also sicher sagen, dass Blum 39,5 Meter Vertov<br />

in seinen Film kompiliert hat, was – bei 20 Bildern pro Sekunde – etwa 103 Sekunden<br />

entspricht.<br />

Das Finale von Im Schatten der Maschine besteht darüber hinaus aus 39 zusätzlichen,<br />

rasant montierten Einstellungen. So gut wie alle diese Bilder verweisen auf Vertovs Film,<br />

wie wir ihn kennen – manchmal sind sie mit Einstellungen aus Odinnadcatyj ident, in<br />

manchen Fällen sind es Variationen auf uns bereits bekannte Einstellungen. Wir können<br />

also annehmen, dass zumindest ein Teil des verlorenen Finales von Odinnadcatyj in Blums<br />

Kompilation erhalten ist.<br />

Laut eigenen Angaben hat Blum aber 86 Meter aus Odinnadcatyj entwendet – eine<br />

Metrage, die sich selbst unter Einbeziehung dieses vermeintlichen Finales nicht verifizieren<br />

lässt. Hat Blum sich bei der Niederschrift dieser Meterangabe schlicht geirrt? Oder bezieht<br />

sich seine Längenangabe auf das gesamte Teilstück, das er zur Nachbearbeitung aus der<br />

Kopie entfernt hatte? Manche Fragen bleiben auch weiterhin offen.<br />

Adelheid Heftberger, Aleksandr Derjabin<br />

Der ROM-Bereich auf Disc 2 enthält ein ausführlicheres Dossier zur „Affäre Blum“<br />

Shadow of a doubt<br />

Odinnadcatyj and Im Schatten der Maschine<br />

The Blum Affair<br />

When Dziga Vertov traveled abroad for the first time in May of 1929, screening excerpts of<br />

his film Odinnadcatyj (The Eleventh Year) during his lectures at German film clubs, the press<br />

accused him of plagiarism. He supposedly used scenes from the German film In the Shadow<br />

of the Machine by Albrecht Viktor Blum and Leo Lania in his film The Eleventh Year without<br />

crediting them. Vertov was perplexed because the opposite was true: his film had not yet<br />

been shown in Germany, and was ransacked by Blum and Lania for their compilation.<br />

In mid-October of 1928 Austrian communist activist Albrecht Viktor Blum received the<br />

commission to produce an “exemplary short” for the VFV (Volksfilmverband) entitled In<br />

the Shadow of the Machine by the head of VFV, author-playwright Leo Lania. The film<br />

was produced as a compilation film. Blum reported in Film-Kurier (5.11.1928): “It will be<br />

assembled from excerpts of partly unpublished Ukrainian films. […] Some American footage<br />

has also been used. To get material as impressive as possible, a number of films, 50–60,<br />

have been viewed.”<br />

What is interesting, from a methodological point of view, is the fact that Blum, through<br />

his editing, instills the images with a reverse meaning: enthusiasm for technical progress<br />

turns into its criticism. As he described it in his own words: “The machine invented by man<br />

to serve man progressively turns into man’s master. Indeed, in the end, man will be no<br />

more than a handyman, a slave of the machine itself.” This concept stems from Lania who<br />

had developed it earlier in his report “Machine and Poetry” (Arbeiter-Zeitung, 22.11.1927).<br />

Presseartikel aus der Vertov-Sammlung /<br />

Press clippings from the Vienna Vertov<br />

Collection

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 16<br />

The film’s techno-critical intention is due to the German proletarian context for which<br />

the film was made: Under capitalist conditions, workers perceive technology as mere<br />

rationalization and Taylorization.<br />

Blum’s film consists mainly of the 5 th reel of Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Zvenigora (SU 1928)<br />

and the last part of Dziga Vertov’s Odinnadcatyj. According to Blum, he had inte grated<br />

282 feet (= 3’50’’ at 20 frames per sec) from Vertov’s film almost unaltered into his own<br />

film, as “these passages already included the thoughts to be expressed.” But there is no<br />

mention, for example, of his intervention in the footage by inserting title cards.<br />

This prompted Vertov to defend himself vehemently in the press against these accusations,<br />

although the Soviet Trade Commission wanted to hush up the affair for political reasons.<br />

Vertov regarded the matter as a legal affair of copyright infringement and plagiarism. Blum<br />

stated that his patron, Weltfilm, stopped him from naming the sources for his film because<br />

of import quota regulations. To be declared a German film by the censorship committee,<br />

it had to be free of any foreign material.<br />

Thomas Tode<br />

Trailing the footage<br />

As with many of Dziga Vertov’s films, the original shape of The Eleventh Year remains unclear.<br />

According to “Repertuarnyj bulletin“ and “Repertuarnyj ukazatel,“ the original length of<br />

the film was 5,250 feet. Other sources say it was only 4,685 feet. The print preserved at<br />

Gosfilmofond of Russia and the Austrian Film Museum measures 4,032 feet. As of yet, there<br />

is no definite explanation for these differences. There are no records of another version of<br />

the film to be found in the Russian press or the Vertov archive in Moscow. A comparison<br />

of the intertitles in the existing copy with a list of intertitles from a 1928 autograph in the<br />

Vertov collection at the Austrian Film Museum shows some interesting divergences. Seven<br />

title cards are missing from the print, which were all meant to appear at the beginning<br />

and end of a film reel. This is documented in the Rom section on this DVD.<br />

In any case, the existing copy of The Eleventh Year has most likely not been a victim<br />

of censorship. Already in the second half of 1931, the film was pulled from distribution;<br />

therefore there was no need to create a new version. It seems more plausible that VUFKU<br />

reused the footage for different purposes. Film director Abram Room used parts of the<br />

original negative when he edited his compilation film Pjatiletka. Unfortunately, this<br />

work cannot support a reconstruction of lost sequences from Vertov’s film – Pjatiletka is<br />

considered a lost film. It is also possible that Vertov himself reused parts of the negative in<br />

the making of Man with a Movie Camera (which he finished shortly after the premiere of<br />

The Eleventh Year), Enthusiasm and Three Songs of Lenin. Vertov’s concept of an “author’s<br />

filmotheque” which he documented in diagrams and writings as a register of shots which<br />

can be reused in various contexts, would solidify this theory. In the canonical “editing<br />

room” sequence of Man with a Movie Camera, which visualizes this concept, one can<br />

spot numerous duplicates and alternative takes of motives and subjects known from<br />

The Eleventh Year. In Three Songs of Lenin there is a long sequence of shots depicting<br />

the construction of the Dnepr Hydroelectric Station – which is quite similar to subjects<br />

described by Vertov in an autograph on Odinnadcatyj (V 72 in the Vienna Vertov Collection).<br />

The project Digital Formalism verified the contradicting references to the original length<br />

of the film for the first time, systematically and extensively. First, all takes from The Eleventh<br />

Year were manually annotated, and then compared with Blum’s German compilation film<br />

via automatic shot identification. Blum’s statement about the use of footage from Vertov’s<br />

film could now be evaluated based on the actual footage. Altogether, 30 takes from In the<br />

Shadow of the Machine were identified as stemming from The Eleventh Year; all but one<br />

from the last reel. Further, each of the identical shots was juxtaposed frame by frame<br />

(sometimes Blum only used parts of a shot) with its respective take from Vertov’s film to<br />

Odinnadcatyj, Im Schatten der Maschine<br />

determine the exact number of frames. We can safely say that Blum compiled 129.6 feet of<br />

Vertov’s film in his own film, which equals – at 20 frames per second – about 103 seconds.<br />

The ending of In the Shadow of the Machine consists of an additional 39 rapidly edited<br />

shots. Almost all of these images refer to Vertov’s film as we know it – sometimes they are<br />

identical to The Eleventh Year, and sometimes they are variations on familiar shots. We may<br />

therefore assume that parts of the lost ending of The Eleventh Year have been preserved in<br />

Blum’s compilation. According to Blum, he used 282 feet from The Eleventh Year – a claim<br />

which cannot be verified, even when adding the alleged ending. Was Blum simply mistaken?<br />

Or does the length specification refer to the entire length of the reel from which he<br />

‘borrowed’ the original? So far, we have only identified a single take as stemming from<br />

The Eleventh Year, which as such does not exist in the film anymore. Some questions will<br />

remain unanswered.<br />

Adelheid Heftberger, Aleksandr Derjabin<br />

The ROM section on Disc 2 contains an extended version of this article as well as some<br />

original documents of the “Blum affair”.

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 18<br />

Odinnadcatyj © Lev Manovich

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 20<br />

Plakate zu / Posters for Šestaja čast’ mira und / and<br />

Odinnadcatyj, <strong>Österreichisches</strong> <strong>Filmmuseum</strong>

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 22<br />

Die Musik<br />

Michael Nyman ist einer der prominentesten zeitgenössischen Komponisten Großbritanniens.<br />

In den späten 1960er Jahren prägte er als Musikkritiker den Begriff „Minimalismus“, der<br />

seither als Genrebezeichnung für seine eigenen Kompositionen verwendet wird. Sein Œuvre<br />

umfasst Opern und Streichquartette, Filmkompositionen und Orchesterwerke; 1976 gründete<br />

er die Campiello Band, aus der später die Michael Nyman Band hervorging. Neben seiner<br />

Tätigkeit als Komponist tritt er als Performer, Dirigent, Bandleader, Pianist, Autor, Musik -<br />

wissenschaftler und, seit kurzem, auch als Fotograf und Filmemacher in Erscheinung.<br />

Seit mehr als drei Jahrzehnten wird Michael Nyman für seine Filmkompositionen geschätzt,<br />

darunter die stilbildenden Soundtracks für die Filme von Peter Greenaway (wie etwa The<br />

Draughtsman’s Contract und The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover ), für Jane Campions<br />

The Piano, den Science-Fiction-Film Gattaca sowie für Filme von Michael Winterbottom<br />

und Neil Jordan.<br />

2002 komponierte Nyman einen neuen Soundtrack für Dziga Vertovs Stummfilm Der Mann<br />

mit der Kamera, den die Michael Nyman Band auch für eine DVD einspielte. Seit 2006<br />

arbeitet er intensiv mit dem Österreichischen <strong>Filmmuseum</strong> und der dort bewahrten Vertov-<br />

Sammlung. Das Resultat dieser Zusammenarbeit sind neue Kom positionen zu Vertovs<br />

Kinopravda 21, Ein Sechstel der Erde sowie Das Elfte Jahr. Die Musik zu letzterem wurde<br />

im August 2009 bei »pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar uraufgeführt.<br />

The Music<br />

As one of Britain’s most innovative and celebrated composers, Michael Nyman’s work encompasses<br />

operas and string quartets, film soundtracks and orchestral concertos. Far more than<br />

merely a composer, he’s also a performer, conductor, bandleader, pianist, author, musi -<br />

cologist and now a photographer and filmmaker. Nyman first made his mark on the musical<br />

world in the late 1960s, when he invented the term ‘minimalism.’ His reputation is built<br />

upon an enviable body of work written for a wide variety of ensembles including not only<br />

his own band, but also symphony orchestra, choir and string quartet. He has also written<br />

widely for the stage, and he has provided ballet music for a number of the world’s most<br />

distinguished choreographers. In 1976 he formed his own ensemble, the Campiello Band<br />

(now the Michael Nyman Band) and over three decades and more, the group has been<br />

the laboratory for much of his inventive and experimental compositional work.<br />

For more than 30 years, he had also enjoyed a highly successful career as a film<br />

composer. His most notable scores number a dozen Peter Greenaway films, including<br />

such classics as The Draughtsman’s Contract and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover;<br />

Neil Jordan’s The End Of The Affair; several Michael Winterbottom features including<br />

Wonderland and A Cock And Bull Story; the Hollywood blockbuster Gattaca and his music<br />

for Jane Campion’s 1993 film The Piano. In 2002 he composed and recorded (with the<br />

Michael Nyman Band) a new score for Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (released<br />

on DVD by the BFI) and since 2006 he has been working closely with the Austrian Film<br />

Museum’s Vertov collection composing and performing music for Vertov’s Kinopravda 21,<br />

A Sixth Part of the World and The Eleventh Year, the latter of which was premiered live at<br />

»pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar (Germany) in August 2009.<br />

www.michaelnyman.com<br />

www.mnrecords.com<br />

© Kunstfest Weimar/Maik Schuck

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 24<br />

Odinnadcatyj<br />

Gabrielle Lester . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Violin<br />

Catherine Thompson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Violin<br />

Catherine Musker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Viola<br />

Anthony Hinnigan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Cello<br />

Martin Elliott . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bass guitar<br />

Simon Haram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Soprano sax<br />

David Roach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Alto sax<br />

Andrew Findon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Baritone sax, flute, piccolo<br />

Steve Sidwell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Trumpet<br />

David Lee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . French horn<br />

Nigel Barr . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bass trombone<br />

David Arch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Piano<br />

Paul Spong . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Orchestral contractor<br />

Michael Nyman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Musical Director<br />

Engineer: Austin Ince<br />

Assisted by: Mat Bartram<br />

Produced by: Michael Nyman and Austin Ince<br />

Recorded at: Angel Studios London on 15, 16, 17 October 2009<br />

Mixed, edited and mastered by:<br />

Austin Ince at Angel Studios London on 3 and 4 November 2009<br />

Šestaja čast mira<br />

Gabrielle Lester . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Violin<br />

Catherine Thompson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Violin<br />

Catherine Musker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Viola<br />

James Boyd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . viola<br />

Anthony Hinnigan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Cello<br />

Martin Elliott . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bass guitar<br />

Simon Haram. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Soprano sax<br />

David Roach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Alto sax<br />

Andrew Findon. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Baritone sax, flute, piccolo<br />

Jamie Talbot. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Baritone saxophone<br />

Rob Buckland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Baritone sax<br />

Anna Noakes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Flute and piccolo<br />

Steve Sidwell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Trumpet<br />

Nigel Gomm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Trumpet<br />

David Lee. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . French horn<br />

Nigel Barr . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bass trombone<br />

Andrew Vinter and Simon Chamberlain . . . Piano<br />

Paul Spong . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Orchestral contractor<br />

Michael Nyman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Musical Director<br />

Engineer: Austin Ince<br />

Assisted by: Mat Bartram<br />

Produced by: Michael Nyman and Austin Ince<br />

Recorded at Angel Studios London on 17 October and 3 & 9 November 2009<br />

Mixed, edited and mastered by: Austin Ince at Angel Studios London on 14 November 2009 © Kunstfest Weimar/Maik Schuck

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 26<br />

Technische Anmerkungen<br />

Michael Loebenstein<br />

Die vorliegende Doppel-Edition von Dziga Vertovs Filmen stellt editorisch wie technisch eine<br />

beträchtliche Anstrengung dar. DVD-Editionen sind unserer Ansicht nach ein „Apparat“ zum<br />

Filmereignis – mittels digitaler Technologien werden „Abschriften“ des ursprünglich für den<br />

Kinoraum gedachten und mittels analoger Filmtechnologie hergestellten Werkes einer breiten<br />

Öffentlichkeit zugänglich gemacht. Zugleich vermittelt der digitale Gegenstand DVD auch<br />

Wissen über einen bestimmten Autor und seine Arbeit: Veröffentlichungen wie jene in<br />

der Edition <strong>Filmmuseum</strong> dienen auch dazu, wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse aufzubereiten,<br />

die im Zusammenspiel zwischen Archiven, Museen, der Kunst und den Wissenschaften<br />

produziert werden.<br />

Die Filme Dziga Vertovs sind dabei eine spezielle Herausforderung. Zum einen antizipiert<br />

der Filmemacher und Theoretiker in vielen seiner Methoden digitale Verfahren. Zum anderen<br />

sind die von ihm erhaltenen Filme geprägt von der Idee eines „Kino-Auges“, das eben<br />

nicht nur filmt, sondern sich auch erst in der analogen Projektion, im Kinosaal, im<br />

Rhythmus der Flügelblende und in gleißendem 35mm-Schwarzweiß entfaltet. Nicht zuletzt<br />

zeugen die Filme auch von der zerstörerischen Kraft der Entropie, der das ursprüngliche<br />

Material unterworfen ist: Sie sind zum Teil stark beschädigt und vermutlich unvollständig<br />

überliefert.<br />

Im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts Digital Formalism konnten Vertovs Langfilme erstmals<br />

vollständig digitalisiert und Kader für Kader analysiert werden. Die Resultate dieser interdisziplinären<br />

Recherche finden Sie sowohl im Video-Feature Vertov in Blum auf Disc 2 als<br />

auch in den interaktiven Demonstrationen und Recherche-Dossiers im ROM-Bereich der<br />

Disc. In beiden Features liegt der Film Odinnadcatyj (beziehungsweise die Ausschnitte<br />

daraus) kadergenau digitalisiert vor. Vertovs Filme wurden, wie zur Zeit des Stummfilms<br />

üblich, mit variabler Geschwindigkeit gedreht und mit einer niedrigeren Bildfrequenz als<br />

den auf Video und im TV üblichen 25 Bildern/Sekunde wiedergegeben. Um eine exakte<br />

Wiedergabe jedes Bilds ohne zusätzlich erzeugte, interpolierte Kader zu gewährleisten, wird<br />

Vertovs Material im wissenschaftlichen Apparat der DVD also subjektiv zu schnell abgespielt.<br />

Für eine DVD-Edition der Filme selbst ist dies jedoch kein gangbarer Weg. Technisch<br />

haben wir versucht, einen Mittelweg zwischen Werktreue und editorischer Praxis zu finden.<br />

Um die Analyse im Projekt Digital Formalism zu optimieren, aber auch die Qualität des DVD-<br />

Release zu garantieren, wurden Šestaja čast’ mira und Odinnadcatyj mit Unterstützung von<br />

ZDF / ARTE in HD-Auflösung (1920 1080 Pixel) mit 25 Bildern/Sekunde auf HDCam transferiert.<br />

Als Quelle dienten die Sicherungspositive der Filme, die dem Österreichischen <strong>Filmmuseum</strong><br />

in den späten 1960er Jahren vom Gosfilmofond (Moskau) übergeben wurden, und die eine<br />

erstaunliche Bildqualität aufweisen. Anschließend wurde digital vor allem jene Bildkorrektur<br />

durchgeführt, die bei der ‚Live-Vorführung‘ in einer Cinematheque vom Vorführer übernommen<br />

wird: Der Bildstand, der aufgrund unterschiedlicher Schrumpfung und Beschädigungen<br />

des Streifens sowie durch analoge Kopierfehler uneinheitlich ist, wurde angepasst. Weiters<br />

wurden wenige Kader lange Reste „falschen“ Materials (Spring titel-Reste, einkopierte<br />

© Interactive Media Systems Group, TU Wien<br />

Überblendzeichen) und mitkopierte Klebestellen mittels Software von Adobe und Apple<br />

entfernt. Ein großes Problem stellte am Ende die Herstellung der „korrekten“ Laufgeschwin -<br />

digkeit dar: Ein groteskes Defizit der neuen digitalen Audio visionen – von DVD über BluRay<br />

bis zum Digitalen Kino – ist ihr Unvermögen, variable Bildfrequenzen zuzulassen. Um auf<br />

das Äquivalent von 18 oder 20 Bildern pro Sekunde zu kommen, müssen von der Software<br />

in jeder Sekunde 5–7 zusätzliche Bilder errechnet werden. Diese duplicate frames bzw.<br />

interpolated frames sind nicht nur Bilder, die der Autor nie gemacht hat; sie produzieren<br />

auch digitale „Artefakte“ (in diesem Fall sind damit „Fehler“ gemeint), die den Filmeindruck<br />

beeinträchtigen.<br />

Nun leben wir in keiner perfekten Welt; das Ziel war vor allem, dem Eindruck von Vertovs<br />

Filmen keinen Abbruch zu tun. Gewählt wurde letztlich, nach einer Vielzahl von Experi -<br />

menten in Wien (Alexandra Braschel) und München, wo Christian Ketels die Postproduktion<br />

von Šestaja čast’ mira besorgte, eine Mischform aus frame duplication (jeder dritte bis<br />

fünfte Kader wird dupliziert) und frame blending (alle fünf Kader wird aus zwei benach -<br />

barten Bildern ein neues, überblendetes Bild produziert). Einstellung für Einstellung wurde<br />

– je nach Bewegungsgrad der Szene – zwischen blending und duplication abgewogen.<br />

Bis die Unterhaltungsindustrie die Forderung der internationalen Filmarchive nach einem<br />

Bildfrequenz-agnostischen digitalen Standard anerkennt, bleibt dies die einzige Möglichkeit.

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 28<br />

© Interactive Media Systems Group, TU Wien<br />

Technical notes<br />

Michael Loebenstein<br />

This DVD publication of two films by Dziga Vertov represents a major editorial and technical<br />

undertaking. In our opinion, the DVD medium is an “apparatus” that does not supplant<br />

but complements the actual film experience – a means of making available digital “transcriptions”<br />

of filmic works which were originally intended for the cinema and created<br />

via analog technology. In addition, the digital contents of a DVD can communicate infor -<br />

mation about a specific author and his or her films. Publications like those in the Edition<br />

<strong>Filmmuseum</strong> series disseminate the results of scholarly work, stemming from an interplay<br />

of archives, museums, art and science.<br />

In this context, the films of Dziga Vertov pose a special kind of challenge. On the one<br />

hand, the filmmaker and theorist anticipated digital processes in many of his chosen methods.<br />

On the other hand, Vertov’s surviving films were formed from the idea of a “Kino Eye”<br />

which not only records images but also reveals itself primarily in analog projection, in the<br />

cinema, in the rhythm of the shutter blade and the glistening 35mm black and white celluloid.<br />

Not least, the films testify to the destructive force of entropy to which the original<br />

material is subject: they have been handed down to us in partly damaged or incomplete<br />

form.<br />

As part of the research project Digital Formalism, Vertov’s feature films could, for the<br />

first time, be digitised and analysed frame-by-frame in their entirety. The results of this<br />

interdisciplinary research can be seen both in the supplementary video feature, Vertov<br />

in Blum, and the interactive demonstrations and research dossiers available in the ROM section<br />

on Disc 2. In both cases, excerpts from the film Odinnadcatyj are digitally represented<br />

frame-for-frame. As was customary during the silent period, Vertov shot his films at varying<br />

speeds, and the films were projected at a frame rate below that of the European video and<br />

television standard of 25 frames per second. For study purposes, however, it is necessary<br />

to ensure that each frame is reproduced exactly, without creating additional interpolated<br />

frames. This means that the film speed in the research sections will appear as “too fast”.<br />

For a DVD edition of the actual films, this is not an acceptable solution. We have<br />

therefore attempted to define a technical half way point between remaining true to the<br />

original and exercising editorial practice. In order to better facilitate the analyses for<br />

the “Digital Formalism” project, and at the same time guarantee the quality of the DVD<br />

release, Šestaja čast’ mira and Odinnadcatyj were transferred to HDCAM in HD-resolution<br />

(1920 1080 pixels) at 25 frames per second. The positive prints given to the Austrian Film<br />

Museum by Gosfilmofond of Russia in the late 1960s – exhibiting very good picture quality<br />

– served as sources for the transfers. The major digital “correction” is an equivalent to what<br />

the projectionist would do during a “live” archival screening: adjusting the unsteady frame<br />

line of the image (the result of varying degrees of shrinkage or damage to the material and<br />

of analogue copying errors). Furthermore, “defects” of only a few frames in length (such<br />

as remaining flash titles and reel change-over marks) were eliminated using Adobe and<br />

Apple software.<br />

Achieving the “correct” frame rate posed a particularly challenging problem. The most<br />

bizarre deficiency of new digital audiovisual media, from DVD or Blu-Ray to Digital Cinema,<br />

is their inability to accommodate variable frame rates. To achieve the equivalent of 18 or<br />

20 frames per second, 5 to 7 additional frames must be generated electronically. These<br />

“duplicate” or “interpolated” frames are images that were never created by the author –<br />

and they produce digital “artefacts” (meaning “errors”, in this case) which compromise<br />

the film effect.<br />

We do not live in a perfect world; the effort boils down to ensuring that we do not<br />

detract from the effect of Vertov’s films. Ultimately, after numerous experiments made by<br />

Alexandra Braschel in Vienna and by Christian Ketels, who carried out the post-production<br />

work on Šestaja čast’ mira in Munich, we chose a hybrid of “frame duplication” (where<br />

every third to fifth frame is reproduced) and “frame blending” (where the additional frames<br />

are created by combining two adjacent frames). By carefully analysing the degree of movement<br />

within the image in each shot, we ascertained which of the two methods would be<br />

preferable for that particular shot. Until the entertainment industry acknowledges the cry<br />

of the International Federation of Film Archives for a frame rate agnostic digital standard,<br />

this procedure remains the only possibility.<br />

Über den ROM-Bereich / About the ROM features<br />

Disc 2 enthält einen computernutzbaren ROM-Bereich mit zum Teil interaktiven Materialien<br />

zu Odinnadcatyj und dem Projekt Digital Formalism. Um diese Features zu nutzen, be -<br />

nötigen Sie einen Webbrowser sowie eine neuere Version des Adobe Flash Plugins und<br />

das Quick Time Plugin. Zum Starten öffnen Sie die Datei INDEX.HTM im Ordner ‚ROM‘ auf der<br />

DVD. Eine Internetverbindung ist nicht zwingend nötig, aber nützlich, um zusätzliche<br />

Inhalte auf verlinkten Webseiten zu betrachten.<br />

Disc 2 contains additional documents and interactive applications which can be accessed<br />

and explored on a computer. The ‘ROM’ folder on the disc’s root level contains an intro -<br />

duction to research done on Odinnadcatyj in the context of the project Digital Formalism.<br />

To access this feature please open INDEX.HTM in your computer’s web browser. The latest<br />

version of the Adobe Flash plugin and Quick Time player must be installed. An active<br />

internet connection is not mandatory but recommended to explore external links.

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 30<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira<br />

Ein Sechstel der Erde / A Sixth Part of the World<br />

Sowjetunion 1926 / Soviet Union 1926<br />

Regie / Directed by: Dziga Vertov<br />

Assistentin und Schnitt / Assistant and editor: Elizaveta Svilova<br />

Hauptkamera / Director of Photography: Michail Kaufman<br />

Kamera / Camera team: I. Beljakov, S. Benderskij, P. Zotov, N. Konstantinov,<br />

A. Lemberg, N. Strukov, J. Tolčan<br />

Produziert von / Produced by: Goskino (Moskau / Moscow)<br />

Vertrieb / Distributor: Sovkino<br />

Premiere / Première: 19. 10. 1926, Berlin<br />

Originalformat / Original format: 35mm, schwarzweiß / black & white<br />

Länge / Runtime: 73’ (18 Bilder/Sekunde / 18 frames per second)<br />

HD-Transfer vom 35mm-Sicherungspositiv<br />

HD Telecine from the 35mm preservation positive<br />

Odinnadcatyj<br />

Das Elfte Jahr / The Eleventh Year<br />

Sowjetunion 1928 / Soviet Union 1928<br />

Regie / Directed by: Dziga Vertov<br />

Assistentin und Schnitt / Assistant and editor: Elizaveta Svilova<br />

Kamera / Photography by: Michail Kaufman<br />

Labortechniker / Lab technician: I. Kotelnikov<br />

Produziert von / Produced by: VUFKU (Kiew / Kiev)<br />

Premiere / Première: 21. 3. 1928, Kiev<br />

Originalformat / Original format: 35mm, schwarzweiß / black & white<br />

Länge / Runtime: 53’ (20 Bilder/Sekunde / 20 frames per second)<br />

HD-Transfer vom 35mm-Sicherungspositiv<br />

HD Telecine from the 35mm preservation positive<br />

Im Schatten der Maschine. Ein Montagefilm<br />

In the Shadow of the Machine. A Compilation Film<br />

Deutschland 1928 / Germany 1928<br />

Regie / Directed by: Albrecht Viktor Blum, Leo Lania<br />

Produziert von / Produced by: Filmkartell „Weltfilm“ (Berlin)<br />

Vertrieb / Distributor: Prometheus Film (Berlin)<br />

Premiere / Première: 9. 11. 1928, Tauentzien-Palast (Berlin)<br />

Originalformat / Original format: 35mm, schwarzweiß / black & white<br />

Länge / Runtime: 22’ (20 Bilder/Sekunde / 20 frames per second)<br />

Transfer vom 35mm-Sicherungspositiv im Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, Berlin<br />

Telecine from the 35mm preservation positive courtesy of Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, Berlin<br />

Vertov in Blum. Eine Untersuchung<br />

Vertov in Blum. An Investigation<br />

Österreich 2009 / Austria 2009<br />

Konzept / Concept: Adelheid Heftberger, Michael Loebenstein, Georg Wasner<br />

Schnitt / Edited by: Michael Loebenstein, Georg Wasner<br />

Sprecher / Narrated by: Georg Wasner (Deutsch), Kellie Rife (English)<br />

Tonaufnahme / Audio Engineer: Christoph Amann (Amann Studios, Wien)<br />

Mitarbeit / Collaborators: Aleksandr Derjabin, Lev Manovich, Dalibor Mitrovic,<br />

Thomas Tode, Maia Zaharieva, Matthias Zeppelzauer<br />

Originalformat / Original format: DigiBeta PAL, Farbe und schwarzweiß /<br />

Colour and black & white<br />

Länge / Runtime: 14’<br />

Dank an / Thanks to: Ulrich Hauschild, Constanze Lehmann, Thomas Scheider, Nike Wagner<br />

(»pèlerinages«, Weimar); Barbara Lebitsch (Wiener Konzerthaus); Nina Goslar (ZDF/ARTE,<br />

Mainz); Annette Gentz & Matthias Schneider (gentz & schneider musik kultur management,<br />

Berlin); Andrea B. Braidt, Anton Fuxjäger, Klemens Gruber, Stefan Hahn (TFM, Universität<br />

Wien); Christian Breiteneder (TU Wien); Karl Griep, Barbara Schütz (Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv,<br />

Berlin); Hans-Michael Bock, Erika Wottrich (CineGraph, Hamburg); Mark-Paul Meyer<br />

(Nederlands <strong>Filmmuseum</strong>, Amsterdam); Oksana Sarkisova (Budapest); John MacKay<br />

(Yale University, New Haven); Yuri Tsivian (University of Chicago); Paolo Cherchi Usai<br />

(Haghefilm Foundation, Amsterdam); Dieter Pichler (Wien)<br />

Im Schatten der Maschine erscheint mit großzügiger Unterstützung des Bundesarchiv-<br />

Filmarchiv, Berlin / In the Shadow of the Machine is presented courtesy of Bundesarchiv-<br />

Filmarchiv, Berlin.<br />

Die Musik zu Odinnadcatyj ist ein Auftragswerk von »pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar<br />

in Kooperation mit ZDF und ARTE. Die Musik zu Šestaja čast’ mira ist ein Auftragswerk<br />

der Wiener Konzerthausgesellschaft. / The music for Odinnadcatyj was commissioned<br />

by »pèlerinages« Kunstfest Weimar in cooperation with ZDF and ARTE. The music for<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira was co-commissioned by Vienna Konzerthaus.<br />

The music of Michael Nyman is published exclusively by Chester Music Ltd/Michael Nyman Ltd

53 VertovSestaja_booklet:ef 14.12.2009 11:42 Uhr Seite 32<br />

Dziga Vertov<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira | Odinnadcatyj<br />

Musik von / Music by Michael Nyman<br />

Šestaja čast’ mira 1926, 73’<br />

Odinnadcatyj 1928, 53’<br />

Im Schatten der Maschine. Ein Montagefilm 1928, 22’<br />

Vertov in Blum. Eine Untersuchung 2009, 14’<br />

ROM-Bereich für Computer-Nutzung (PC und Mac) mit zusätzlichen Materialien zu<br />

Odinnadcatyj /ROM section for PC and Mac with additional materials about Odinnadcatyj<br />

DVD Credits<br />

DVD-Supervision: Michael Loebenstein, mit / with Adelheid Heftberger, Georg Wasner<br />

DVD-Authoring: Ralph Schermbach<br />

Tonbearbeitung / Sound mastering: Gunther Bittmann, Ernst Schillert<br />

Videobearbeitung / Video postproduction: Alexandra Braschel (Golden Girls Filmproduktion,<br />

Wien), Eshna Pur (sernerwerk, Wien), Christian Ketels (cktv&film, München)<br />

Telecine: Karl Kopecek (Synchro Film & Video, Wien),<br />

Willi Willinger (Listo film:video:effects, Wien)<br />

Untertitelung / Subtitles: Titra Film, Wien<br />

Übersetzungen / Translations: Adelheid Heftberger (Extras, Untertitel / Subtitles) Oliver Hanley<br />

(<strong>Booklet</strong>, Untertitel / Subtitles), Natascha Unkart & Kellie Rife (Extra feature, <strong>Booklet</strong>)<br />

ROM-Programmierung / Rom content authoring: Christian Störzer (brainiacs, Wien)<br />

Design & Layout <strong>Booklet</strong>: Gabi Adébisi-Schuster<br />

Layout Inlay: Heiner Gassen<br />

Coverfoto / Cover photo: Odinnadcatyj<br />

Mitarbeit / Contributors: Andrea Glawogger, Richard Hartenberger, Alexander Horwath, Walter<br />

Moser, Florian Wrobel (<strong>Österreichisches</strong> <strong>Filmmuseum</strong>); Vera Kropf, Barbara Vockenhuber,<br />

Barbara Wurm (TFM, Wien); Dalibor Mitrovic, Maia Zaharieva, Matthias Zeppelzauer (TU Wien);<br />

Thomas Tode (Hamburg); Aleksandr Derjabin (Moskau / Moscow); Lev Manovich, Jeremy<br />

Douglass, Sunsern Cheamanunkul (University of California, San Diego); Raphael Barth<br />

(Golden Girls Filmproduktion, Wien); Dominik Hilleke (ZDF/ARTE, Mainz)<br />

Diese DVD wurde im Rahmen von Digital Formalism, einem vom Wiener Wissenschafts-,<br />

Forschungs- und Technologiefonds WWTF geförderten Projekt hergestellt.<br />

Projektpartner: Institut für Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft an der Universität Wien;<br />

Interactive Media Systems Group – Institute of Software Technology and Interactive Systems<br />

an der Technischen Universität Wien; <strong>Österreichisches</strong> <strong>Filmmuseum</strong>. / The production of<br />

this DVD was made possible through Digital Formalism, a research project funded by<br />

WWTF (Vienna). Project partners: TFM – Institute for Theater-, Film-, and Media Studies<br />

(Vienna University); Interactive Media Systems Group – Institute of Software Technology and<br />

Interactive Systems (Vienna University of Technology); The Austrian Film Museum<br />

www.digitalformalism.org<br />

Das <strong>Filmmuseum</strong> wird gefördert durch die Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien<br />

und das Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur.