annual report 2011 - Office for Research - Northwestern University

annual report 2011 - Office for Research - Northwestern University

annual report 2011 - Office for Research - Northwestern University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

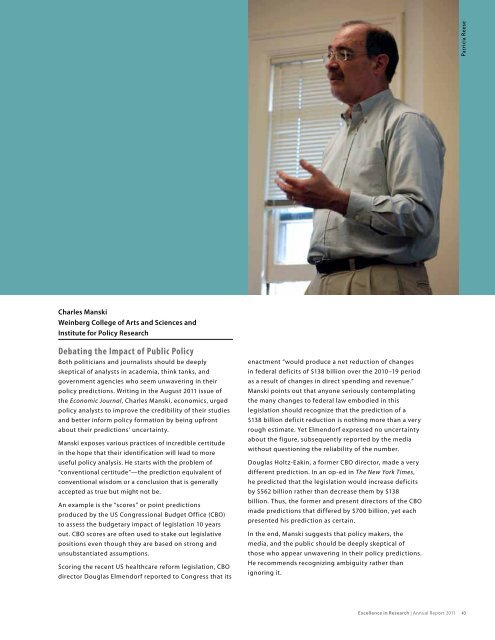

Charles Manski<br />

Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and<br />

Institute <strong>for</strong> Policy <strong>Research</strong><br />

Debating the Impact of Public Policy<br />

Both politicians and journalists should be deeply<br />

skeptical of analysts in academia, think tanks, and<br />

government agencies who seem unwavering in their<br />

policy predictions. Writing in the August <strong>2011</strong> issue of<br />

the Economic Journal, Charles Manski, economics, urged<br />

policy analysts to improve the credibility of their studies<br />

and better in<strong>for</strong>m policy <strong>for</strong>mation by being upfront<br />

about their predictions’ uncertainty.<br />

Manski exposes various practices of incredible certitude<br />

in the hope that their identification will lead to more<br />

useful policy analysis. He starts with the problem of<br />

“conventional certitude”—the prediction equivalent of<br />

conventional wisdom or a conclusion that is generally<br />

accepted as true but might not be.<br />

An example is the “scores” or point predictions<br />

produced by the US Congressional Budget <strong>Office</strong> (CBO)<br />

to assess the budgetary impact of legislation 10 years<br />

out. CBO scores are often used to stake out legislative<br />

positions even though they are based on strong and<br />

unsubstantiated assumptions.<br />

Scoring the recent US healthcare re<strong>for</strong>m legislation, CBO<br />

director Douglas Elmendorf <strong>report</strong>ed to Congress that its<br />

enactment “would produce a net reduction of changes<br />

in federal deficits of $138 billion over the 2010–19 period<br />

as a result of changes in direct spending and revenue.”<br />

Manski points out that anyone seriously contemplating<br />

the many changes to federal law embodied in this<br />

legislation should recognize that the prediction of a<br />

$138 billion deficit reduction is nothing more than a very<br />

rough estimate. Yet Elmendorf expressed no uncertainty<br />

about the figure, subsequently <strong>report</strong>ed by the media<br />

without questioning the reliability of the number.<br />

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a <strong>for</strong>mer CBO director, made a very<br />

different prediction. In an op-ed in The New York Times,<br />

he predicted that the legislation would increase deficits<br />

by $562 billion rather than decrease them by $138<br />

billion. Thus, the <strong>for</strong>mer and present directors of the CBO<br />

made predictions that differed by $700 billion, yet each<br />

presented his prediction as certain.<br />

In the end, Manski suggests that policy makers, the<br />

media, and the public should be deeply skeptical of<br />

those who appear unwavering in their policy predictions.<br />

He recommends recognizing ambiguity rather than<br />

ignoring it.<br />

Patricia Reese<br />

Excellence in <strong>Research</strong> | Annual Report <strong>2011</strong> 43