Container shipping: Successful turnaround - Deutsche Bank Research

Container shipping: Successful turnaround - Deutsche Bank Research

Container shipping: Successful turnaround - Deutsche Bank Research

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

International topics Current Issues<br />

March 28, 2011<br />

Author<br />

Eric Heymann<br />

+49 69 910-31730<br />

eric.heymann@db.com<br />

Editor<br />

Tobias Just<br />

Technical Assistants<br />

Sabine Kaiser<br />

Sabine Berger<br />

<strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> <strong>Research</strong><br />

Frankfurt am Main<br />

Germany<br />

Internet: www.dbresearch.com<br />

E-mail: marketing.dbr@db.com<br />

Fax: +49 69 910-31877<br />

Managing Director<br />

Thomas Mayer<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong>:<br />

<strong>Successful</strong> <strong>turnaround</strong><br />

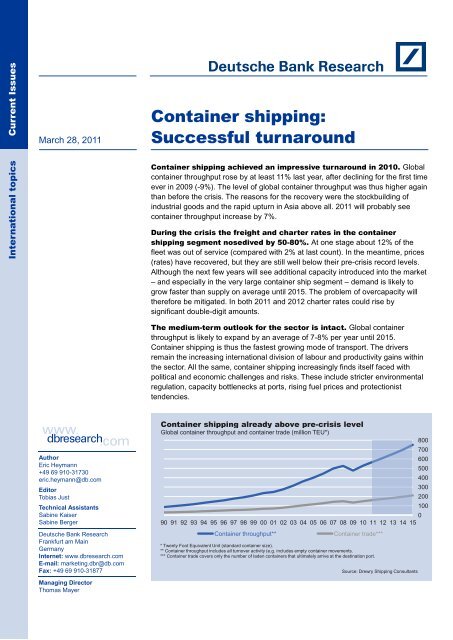

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> achieved an impressive <strong>turnaround</strong> in 2010. Global<br />

container throughput rose by at least 11% last year, after declining for the first time<br />

ever in 2009 (-9%). The level of global container throughput was thus higher again<br />

than before the crisis. The reasons for the recovery were the stockbuilding of<br />

industrial goods and the rapid upturn in Asia above all. 2011 will probably see<br />

container throughput increase by 7%.<br />

During the crisis the freight and charter rates in the container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> segment nosedived by 50-80%. At one stage about 12% of the<br />

fleet was out of service (compared with 2% at last count). In the meantime, prices<br />

(rates) have recovered, but they are still well below their pre-crisis record levels.<br />

Although the next few years will see additional capacity introduced into the market<br />

– and especially in the very large container ship segment – demand is likely to<br />

grow faster than supply on average until 2015. The problem of overcapacity will<br />

therefore be mitigated. In both 2011 and 2012 charter rates could rise by<br />

significant double-digit amounts.<br />

The medium-term outlook for the sector is intact. Global container<br />

throughput is likely to expand by an average of 7-8% per year until 2015.<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> is thus the fastest growing mode of transport. The drivers<br />

remain the increasing international division of labour and productivity gains within<br />

the sector. All the same, container <strong>shipping</strong> increasingly finds itself faced with<br />

political and economic challenges and risks. These include stricter environmental<br />

regulation, capacity bottlenecks at ports, rising fuel prices and protectionist<br />

tendencies.<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> already above pre-crisis level<br />

Global container throughput and container trade (million TEU*)<br />

0<br />

90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15<br />

<strong>Container</strong> throughput** <strong>Container</strong> trade***<br />

* Twenty Foot Equivalent Unit (standard container size).<br />

** <strong>Container</strong> throughput includes all turnover activity (e.g. includes empty container movements.<br />

*** <strong>Container</strong> trade covers only the number of laden containers that ultimately arrive at the destination port.<br />

Source: Drewry Shipping Consultants<br />

800<br />

700<br />

600<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> has<br />

recovered from recession<br />

Global container throughput, % yoy<br />

91 93 95 97 99 01 03 05 07 09<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

-10<br />

Source: Drewry 1<br />

World trade and container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> closely correlated<br />

x-axis: world trade, % yoy<br />

y-axis: container throughput, % yoy<br />

20<br />

R² = 0.73<br />

15<br />

10<br />

-10<br />

-15<br />

-20 -10 0 10 20<br />

Sources: CPB Netherlands, Drewry, DB <strong>Research</strong> 2<br />

The biggest container ports<br />

in the world: Asia dominant<br />

<strong>Container</strong> throughput (million TEU)<br />

Singapore<br />

Shanghai<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Shenzhen<br />

Busan<br />

Guangzhou<br />

Dubai Ports<br />

Ningbo<br />

Qingdao<br />

Rotterdam<br />

Tianjin<br />

Kaohsiung<br />

Port Kelang<br />

Antwerp<br />

Hamburg<br />

Los Angeles<br />

Tanjung Pelepas<br />

Long Beach<br />

Xiamen<br />

Laem Chabang<br />

5<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

0 10 20 30<br />

2000 2009<br />

Source: Hafen Hamburg<br />

3<br />

Current Issues<br />

2009 sees global container throughput sink for the first<br />

time<br />

The global recession of 2008/09 hit the global container <strong>shipping</strong><br />

business hard. Global container throughput fell for the first time in<br />

the annals of the sector in 2009, contracting by over 9%, according<br />

to Drewry Shipping Consultants (Drewry). Prices (freight and charter<br />

rates) fell by between 50% and 80%. At its height some 12% of the<br />

fleet (based on lot capacity in TEU 1 ) was laid up, which means that<br />

at one stage about 600 ships had been taken out of service.<br />

According to information from Germany’s Verband <strong>Deutsche</strong>r<br />

Reeder (VDR), international <strong>shipping</strong> lines suffered losses of USD<br />

20 bn in 2009. The reasons for these losses are obvious: the global<br />

economic crisis was marked by a slump in trading activities and<br />

investment. This had a knock-on effect on container <strong>shipping</strong> since<br />

the fortunes of the sector are very closely correlated with global<br />

trade developments. 2<br />

From a regional standpoint it was the European and North American<br />

ports that were particularly hard hit by the recession. In 2009<br />

container throughput contracted by more than 16% at northern<br />

European ports and by over 13% in North America. The biggest<br />

decline of around 36% was posted by the eastern European ports<br />

(Baltic area, Black Sea, eastern Mediterranean) that are small by<br />

international standards. Several routes were completely suspended<br />

at these ports during the crisis. The decline in 2009 is, however, put<br />

into perspective by the fact that the eastern European ports had<br />

posted the highest growth rates for many years prior to the<br />

recession. Of the world’s 30 biggest ports Hamburg suffered the<br />

biggest decline at 28%. The deep slump in German external trade<br />

was one major reason. On top of this, several feeder services 3 from<br />

Hamburg to the Baltic area were temporarily suspended or transferred<br />

to competing ports (e.g. Rotterdam).<br />

Asian ports were less affected by the crisis as the economic<br />

environment there was much more favourable than in Europe and<br />

the US. In both the Far East and South Asia the decrease in<br />

container throughput in 2009 was about 8%; in the Middle East the<br />

decline was a mere 2%. Several Asian ports even managed to grow<br />

their container throughput in the crisis year of 2009 (e.g. Khor<br />

Fakkan in the United Arab Emirates: +30% to 2.8 m TEU).<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> enjoys multiple advantages<br />

Before the slump in container throughput in 2009 the sector posted<br />

very high growth rates. Between 1990 and 2008, for instance, global<br />

container throughput rose by an annual average rate of more than<br />

10%. The discrepancy between the 2009 figure and the prior longterm<br />

performance highlights the scale of the crisis.<br />

The reasons for the historically very high growth in container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> include the increasing international division of labour and<br />

the growing liberalisation of world trade (e.g. China’s WTO<br />

accession in 2001). Furthermore, the share of goods that are ideal<br />

for <strong>shipping</strong> via container (semis and finished products) has risen<br />

steadily over the last few years, and advances in container<br />

technology allow more and more goods to be transported via<br />

1<br />

TEU stands for Twenty Foot Equivalent Unit and is the usual standard container<br />

size.<br />

2<br />

<strong>Container</strong> throughput invariably grows faster than world trade: between 1991 and<br />

2008 it expanded by 50% more than world trade.<br />

3<br />

Feeder services operate between the larger and smaller ports within a region.<br />

2 March 28, 2011

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong>: <strong>Successful</strong> <strong>turnaround</strong><br />

Asia least affected by the<br />

crisis<br />

<strong>Container</strong> throughput by region based on<br />

biggest ports, 2005=100<br />

140<br />

80<br />

05 06 07 08 09<br />

3.6<br />

Europe Asia<br />

North America<br />

Exports by major trading<br />

nations continue rising<br />

% yoy<br />

CN JP DE US<br />

3.6<br />

5.2<br />

2009 2010 2011<br />

Asia commands large share<br />

of container trade<br />

Individual routes as % of container trade,<br />

2009<br />

28.6<br />

13.4<br />

32.8<br />

12.7<br />

120<br />

100<br />

Sources: Hafen Hamburg, DB <strong>Research</strong> 4<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

-10<br />

-20<br />

-30<br />

Trans-Pacific Europe-Far East<br />

Intra-Asia Intra-Europe<br />

Transatlantic Far East-Middle East<br />

Other<br />

0<br />

Source: DB <strong>Research</strong> 5<br />

Source: Drewry 6<br />

container (e.g. containers for refrigerated goods or liquids). In<br />

addition, container ships possess specific advantages over<br />

traditional general cargo freighters: shorter loading and unloading<br />

times reduce <strong>turnaround</strong> times in the port, which cuts costs. Also,<br />

the options for onward conveyance via other modes of transport are<br />

better with containers than with general cargo. Ever bigger and<br />

faster ships have enabled constant productivity gains, although the<br />

increase in capacity over recent years has cranked up the price<br />

pressure in the sector (see page 5). Extensive investment in port<br />

infrastructure has been and remains essential for fast growth.<br />

Especially in Asia a very large number of container terminals have<br />

been expanded or built from scratch in the last few years. 4 As a<br />

result the containerisation level, that is the proportion of cargo<br />

shipped in containers, has risen worldwide and exceeds 90% at<br />

most of the big ports (Hamburg: 97%; 1990: 69%).<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> celebrates an impressive comeback<br />

Global container <strong>shipping</strong> has managed a complete <strong>turnaround</strong><br />

following the crisis. Global container throughput probably rose by at<br />

least 11% in 2010 (final figures are not yet available). This means<br />

that the record level of 2008 has been bettered again. The key factor<br />

in this recovery was the stockbuilding by the industrial sector and<br />

the swift economic recovery in many countries that was often driven<br />

by external trade. Particularly the upturn in Asia (real GDP ex Japan<br />

2010: +9%) helped to get container <strong>shipping</strong> back on a growth track.<br />

The world’s leading exporter, China, boosted its shipments by more<br />

than 30% in 2010 (2009: -16%). Other Asian economies, too,<br />

bolstered the sector. Overall, container throughput in Asia probably<br />

increased by at least 13% in 2010, whereas North America (+9%)<br />

and Western Europe (+7%) are likely to have achieved only belowaverage<br />

growth (Hamburg: +12.7%).<br />

Asia setting the pace<br />

The focus of the global container <strong>shipping</strong> sector has been steadily<br />

shifting towards Asia in any case over recent years. Some 70% of<br />

global container throughput is handled by ports in Asia. In 2009 nine<br />

out of the ten biggest container ports in the world were in Asia (in<br />

the year 2000 the figure was just five). China is the dominant force<br />

in this respect, being home to six of the current top 10 ports.<br />

Looking at container trade by <strong>shipping</strong> route reveals that at least<br />

one port in Asia is involved in around 80% of all movements. Intra-<br />

Asian routes with a share of one-third are by far the most important<br />

(2007: just 23%). This illustrates that global container <strong>shipping</strong> not<br />

only benefits from the manufacturing in Asia (China) of consumer<br />

goods for western Europe or the US, but that in addition the trade<br />

links and the international division of labour between Asian countries<br />

have also increased significantly. There are individual ports that are<br />

highly specialised in the pure transhipment of containers, thus<br />

operating primarily as hubs for global and regional container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> and handling relatively little local traffic. Overall, besides<br />

China there are smaller developing countries and emerging markets<br />

(e.g. Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam) that are also continually<br />

investing in their port capacities.<br />

A cluster analysis underlines that both the biggest and the fastest<br />

growing container ports are located in Asia. The axes of Figure 8<br />

plot the deviations of the world’s 35 biggest container ports from<br />

4 See Heymann, Eric (2006). <strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong>: Overcapacity inevitable despite<br />

increasing demand. <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> <strong>Research</strong>. Current Issues. Frankfurt am Main.<br />

March 28, 2011 3

Many ports operate mainly<br />

as transhipment hubs<br />

Importance of transhipment at selected<br />

ports* (million TEU)<br />

Singapore<br />

Tanjung Pelepas<br />

Guangzhou<br />

Busan<br />

Shanghai<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Dubai Ports<br />

Kaohsiung<br />

Port Kelang<br />

Salalah<br />

Rotterdam<br />

Algeciras<br />

Gioia Tauro<br />

Colombo<br />

Port Said<br />

Marsaxlokk<br />

Lianyungang<br />

Khor Fakkan<br />

Hamburg<br />

Shenzhen<br />

36.7<br />

4.9<br />

6.6<br />

8<br />

95%<br />

49%<br />

45%<br />

21%<br />

25%<br />

45%<br />

53%<br />

59%<br />

98%<br />

30%<br />

95%<br />

95%<br />

74%<br />

90%<br />

96%<br />

71%<br />

90%<br />

29%<br />

11%<br />

0 10 20 30<br />

* Additional figures show transhipment share.<br />

8.8<br />

35<br />

85%<br />

Source: Drewry<br />

German <strong>shipping</strong> lines lead<br />

the container segment<br />

<strong>Container</strong> fleet by nationality of owner, %<br />

DE JP DK CN GR Other<br />

7<br />

Source: VDR 9<br />

Current Issues<br />

average throughput and average growth between 1999 and 2009.<br />

The upper right quadrant thus contains all the ports whose size and<br />

growth are both above the average for the top 35. Six of the seven<br />

ports in this quadrant are to be found in China.<br />

Cluster analysis based on 35 major ports*: China's<br />

ports are big and growing fast<br />

x-axis: Deviation from average container throughput (million TEU)<br />

y-axis: Deviation from average growth rate (percentage points)<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

Tianjin<br />

10<br />

5<br />

Ningbo<br />

Guangzhou<br />

Qingdao<br />

Dubai Ports<br />

Shanghai<br />

Shenzhen<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

-10<br />

-15<br />

Busan<br />

Rotterdam<br />

Kaohsiung<br />

Singapore<br />

Hong Kong<br />

-10 -5 0 5 10 15 20<br />

Asia (ex China) Other China<br />

* For scale reasons the port of Tanjung Pelepas in Malaysia has been omitted; its container throughput<br />

grew between 1999 and 2009 by an annual average of 64%.<br />

German <strong>shipping</strong> lines lead the container sector<br />

Despite Asia’s dominance with regard to the absolute importance of<br />

container ports and <strong>shipping</strong> it is German <strong>shipping</strong> lines that<br />

continue to top the rankings in terms of the container <strong>shipping</strong> fleet.<br />

In 2009 some 35% of the available lot capacity belonged to German<br />

ship owners. German <strong>shipping</strong> companies are hugely important<br />

especially in the operational charter business. According to VDR,<br />

they command two-thirds of the charter market.<br />

Growth to continue in 2011 at a slower pace<br />

The global economy, which has been boosted by dynamic foreign<br />

trade figures and booming investment, will lose momentum in 2011.<br />

Exports by leading trading nations (such as China, Germany and the<br />

US) are likely to expand during the current year by only about half<br />

as much as in 2010; in Japan the export growth rate could even<br />

drop by more than two-thirds. Global container <strong>shipping</strong> will feel the<br />

effects of this economic cooling. For 2011 we expect a rise in<br />

container throughput by some 7%. Intra-Asian transport as well as<br />

shipments into and out of Asia will probably expand faster than<br />

transatlantic traffic for instance. The reasons for this are Asia’s<br />

greater economic dynamism as well as higher investment in the<br />

necessary port infrastructure. <strong>Container</strong> throughput is also set to<br />

grow until 2015 at an annual average rate of 7-8% (see page 7),<br />

according to the latest market forecasts by Drewry.<br />

Fleet capacity determines prices<br />

Sources: ISL, Hafen Hamburg, Drewry, DB <strong>Research</strong> 8<br />

Fleet capacity growth is a decisive factor for pricing in the sector. As<br />

in basically every sector, prices come under more pressure the<br />

greater the increase in supply. The global container <strong>shipping</strong> sector<br />

has been marked by constant growth in the size of the fleet in recent<br />

years. This has primarily been a consequence of the boom in<br />

demand. Since there is a relatively long period between the placing<br />

of an order for new ships and their delivery – due to the protracted<br />

4 March 28, 2011

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong>: <strong>Successful</strong> <strong>turnaround</strong><br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> fleet<br />

growing constantly<br />

Million TEU<br />

1.6<br />

1.4<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

* Estimate<br />

Charter rates recovered,<br />

but below long-term average<br />

HARPEX* development<br />

2,500<br />

03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10<br />

HARPEX<br />

Average support period<br />

* Aggregate charter rate index<br />

700<br />

600<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10*<br />

Newly built, left Scrapped, left<br />

Fleet, right<br />

2,000<br />

1,500<br />

1,000<br />

500<br />

Sources: Harper Petersen, DB <strong>Research</strong> 11<br />

New ship orders still at<br />

low level<br />

New ship orders in global container<br />

sector<br />

96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10<br />

Lot capacity, million TEU, right<br />

Number of ships, left<br />

0<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

3.5<br />

3.0<br />

2.5<br />

2.0<br />

1.5<br />

1.0<br />

0.5<br />

0.0<br />

Sources: Clarkson <strong>Research</strong> Services, VDR 12<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

Source: Drewry 10<br />

lead times – it is typical for the business that new ships are also<br />

delivered at times when current demand is growing less strongly or<br />

is even shrinking; <strong>shipping</strong> shares this structural feature (“hog<br />

cycle”) with other sectors in which durable goods take a long time to<br />

be produced (e.g. the real estate market, aircraft manufacturing,<br />

parts of the mechanical engineering sector). Cyclical price<br />

fluctuations can become amplified by the considerable time-lag (1 to<br />

3 years) between the placing of an order and delivery of the ship.<br />

The most recent recession is a good example of how large order<br />

backlogs from boom years still have an impact during periods of<br />

crisis and weigh on the earnings situation. Even in crisis-plagued<br />

2009 lot capacity in global container <strong>shipping</strong> grew by 5%. Chinese<br />

shipyards in particular continued to expand their deliveries of<br />

container ships virtually unchecked. The coincidence of falling<br />

supply and rising demand was the main reason for the sector’s huge<br />

drop in rates, which amounted to as much as 80% in the charter<br />

business; this shows the market clout of the liner <strong>shipping</strong><br />

companies compared with that of the charter lines. Smaller<br />

container ships were affected by the decline in part as a result of<br />

renegotiations, such that in many cases debt servicing was no<br />

longer possible; the drop in freight rates for the scheduled lines was<br />

not as high – at up to 50% – due to contracts already in effect.<br />

2009 saw fleet capacity increase, although more than four times as<br />

much capacity was scrapped as in 2008 and although several<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> lines cancelled some of their orders due to the crisis and/or<br />

reached agreement with the shipyards to postpone the delivery of<br />

new ships. Since the container ship fleet as a whole is still very new,<br />

the scope for scrapping is limited; this option is almost only available<br />

for smaller ships (because they are older).<br />

Slow steaming and more laid-up vessels make supply situation<br />

tight<br />

The <strong>shipping</strong> lines reacted to the imbalance between supply and<br />

demand and the resulting plunge in prices by adopting a variety of<br />

measures. Global orders of new container ships fell by more than<br />

90% in 2009. On top of this came the above-mentioned cancelled<br />

orders and postponed deliveries of new ships. All the measures<br />

were insufficient to close the gap between supply and demand in the<br />

short run. There were two other measures that the <strong>shipping</strong> lines<br />

mainly used to prevent another drop in freight and charter rates:<br />

— Shipping companies relied more heavily on slow steaming, that is<br />

slower speeds and thus longer round-trip times for the ships.<br />

This is not a new “instrument”. Back in 2007/08 speeds were<br />

reduced on many routes as a consequence of rising oil prices. At<br />

that time the priority was achieving significantly lower fuel<br />

consumption by reducing speeds. Even a relatively moderate<br />

reduction in speed from 24 to 20 knots can cut the daily fuel<br />

consumption of, for instance, a container ship with a capacity of<br />

8,000 TEU by 40%. Longer sailing times/delivery times and<br />

higher labour and capital costs can be more than offset by such<br />

cost savings. During the most recent crisis lower fuel<br />

consumption continued to be an important argument. The<br />

possibility to also reduce the efficiency of the fleet (i.e. to have<br />

more ships sailing), had however, become much more important.<br />

— Furthermore, the <strong>shipping</strong> lines felt that the implosion in demand<br />

obliged them to lay up – that is temporarily take out of service – a<br />

larger number of container ships. The companies had to face<br />

March 28, 2011 5

Fuel consumption cut by<br />

slow steaming<br />

Speed-dependent (knots) fuel<br />

consumption, tonnes per day<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

24 20.1 17.3<br />

Ship with lot capacity of 8,000 TEU<br />

Ship with lot capacity of 6,000 TEU<br />

Number of laid-up ships<br />

has dropped sharply<br />

Number of laid-up container ships<br />

worldwide during the crisis<br />

0<br />

08 09 10<br />

Number of ships, right<br />

TEU share of total fleet, %, left<br />

250<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

700<br />

600<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

Source: AXS-Alphaliner, VDR 14<br />

0<br />

Source: Drewry 13<br />

Order books for big ships<br />

well filled<br />

Fleet and orders on hand according to<br />

ship size class (million TEU), July 2010<br />

Up to 1,999 TEU<br />

2,000 to 4,999 TEU<br />

5,000 to 7,999 TEU<br />

8,000 to 9,999 TEU<br />

10,000 TEU and<br />

over<br />

0<br />

0 2 4 6<br />

Existing fleet Order book<br />

Source: Drewry 15<br />

Current Issues<br />

laying-up costs of several thousand dollars per day. At its peak<br />

some 12% of the global container <strong>shipping</strong> fleet was idle.<br />

In the end, the reduced lot capacity has helped average freight and<br />

charter rates to pick up again over the last few months – starting<br />

from a very low base of course. Ultimately, however, the key driver<br />

of the latest price increase was the growing demand for <strong>shipping</strong>.<br />

Overall, the level of charter rates is still low anyway on a long-term<br />

comparison.<br />

Further increase in capacity inevitable …<br />

This means that besides the growth in global demand for container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> services it is primarily the ongoing capacity developments<br />

that are of special significance for the future earnings of the <strong>shipping</strong><br />

lines. Further capacity increases can be expected over the short and<br />

medium term. Already over the last few months the number of laidup<br />

ships has fallen dramatically and is currently just around 2% of<br />

the global fleet. With the economy picking up, the market for ship<br />

financing has shaken off the paralysis induced by the months-long<br />

crisis. Around the world, capital is once again flowing into the<br />

financing of container ships. In 2010 more new orders were placed<br />

for container ships after 2009 had brought hardly any new orders;<br />

last year’s orders were still some 40% lower than in 2008.<br />

Overall, the order books still contain a considerable number of<br />

orders placed in the pre-crisis years. Particularly container ships<br />

with a lot capacity of over 10,000 TEU are coming onto the market in<br />

greater numbers, even though it remains to be seen whether they<br />

can also be fully financed. In this segment the ordered capacity in<br />

mid-2010 was equivalent to nearly 400% of the available fleet in this<br />

size category (total fleet: 30%). These ships are ideal for the busy<br />

“expressway” routes, for example, between the Far East and Europe<br />

and North America, and they dock mainly at the big container ports.<br />

… but the likelihood of sufficient rates is higher<br />

All things being equal, the capacity expansion in big container ships<br />

will ramp up price pressure primarily in that segment, but ultimately<br />

across the entire sector. However, most of the big container ships do<br />

not compete directly with smaller ships that mainly provide feeder<br />

services or operate on less busy routes and where the volume of<br />

orders is not nearly so large. In addition, the market entry of ultralarge<br />

ships brings with it the need for smaller feeder vessels. This<br />

makes it very likely that individual routes and certain sizes of ship<br />

will encounter temporary bottlenecks that will probably result in<br />

higher prices.<br />

The friendly economic environment should, however, also allow the<br />

sector as a whole to generate adequate average profits over the<br />

next few years. Also, market observers like Drewry expect that the<br />

demand for container <strong>shipping</strong> will grow faster than the supply of<br />

new capacity over the next few years. And slow steaming is an<br />

option for flexibly adjusting capacity to potentially lower demand.<br />

Slow steaming could even become the rule rather than the<br />

exception for individual <strong>shipping</strong> lines and on particular routes since<br />

many ships have been equipped or refitted accordingly in recent<br />

years. Operating at slower speeds usually also boosts reliability<br />

(meeting delivery deadlines). Of course it is also clear that when<br />

demand rises sharply and rates are high that <strong>shipping</strong> lines will<br />

always seek to increase the number of round-trips per ship.<br />

Overall, the problem of overcapacity has thus eased currently. And<br />

on the demand side, too, the risks are modest at present: we expect<br />

6 March 28, 2011

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong>: <strong>Successful</strong> <strong>turnaround</strong><br />

Supply growing slower than<br />

demand<br />

% yoy, based on TEU<br />

15<br />

08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15<br />

<strong>Container</strong> <strong>shipping</strong> fleet<br />

<strong>Container</strong> throughput<br />

2010: estimates; 2011-2015: forecast<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

-10<br />

-15<br />

Source: Drewry 16<br />

Transhipment share rising<br />

Transhipment as a proportion of<br />

container <strong>shipping</strong><br />

160<br />

120<br />

80<br />

40<br />

0<br />

90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 08 10<br />

Transhipment share, %, right<br />

Transhipment, million TEU, left<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Source: Drewry 17<br />

world trade to grow by 7-8% in both 2011 and 2012. In addition, the<br />

fleet capacity should grow less in both years than the average in the<br />

preceding decade. We have used growth in world trade and fleet<br />

capacity as explanatory variables to forecast the development of the<br />

HARPEX Shipping Index (an aggregate charter rate index) in 2011<br />

and 2012 as part of an econometric model. It forecasts a significant<br />

double-digit increase in this charter rate index in both years. 5<br />

Outlook intact – limiting factors in view<br />

As previously mentioned, the medium-term outlook for container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> remains bright with annual growth in container throughput<br />

expected to average 7-8% until 2015. Going forward, momentum<br />

will continue to be generated by the established stalwarts: the<br />

continuing increase in the international division of labour, rising<br />

incomes and consumption opportunities in many emerging markets<br />

and the thereby initiated trade flows are the most important drivers<br />

on the demand side. Rising incomes in important emerging markets<br />

– above all in China – may also enable the sector to mitigate the<br />

problem of unequal flows and thus reduce the share of empty<br />

container journeys (2009: 21%); this would result in considerable<br />

cost savings. To date, on routes from China to Europe and the US<br />

the share of laden containers is higher than on the return leg.<br />

On the supply side productivity improvements suggest that container<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> will continue to post high growth rates. These include larger<br />

ships (and growing transhipment shares) as well as more efficient<br />

loading and unloading systems at the terminals. In addition, the<br />

containerisation level will increase worldwide; however, the<br />

containerisation level at many ports is already high, which makes a<br />

further increase virtually impossible. Slow steaming cancels out<br />

some of the productivity gains, unless high freight rates make faster<br />

speeds more economically lucrative.<br />

Despite this generally rosy outlook the container <strong>shipping</strong> sector<br />

faces many challenges that may limit its growth potential:<br />

— Maritime <strong>shipping</strong> is becoming the focus of national and<br />

international climate and environmental policy. Discussion is<br />

currently underway about a variety of measures that could<br />

mitigate the negative ecological impact of <strong>shipping</strong> (e.g. CO2 and<br />

pollutant emissions). These include emissions trading, efficiency<br />

standards or reducing the sulphur content in fuels. In the end, the<br />

<strong>shipping</strong> lines face higher costs because they will have to invest<br />

in their fleets in order to comply with the new standards. In<br />

addition, the sector’s competitiveness relative to other modes of<br />

transport is declining. In terms of energy consumption per<br />

transported tonne, though, maritime <strong>shipping</strong> remains the most<br />

efficient mode of transport.<br />

— Capacity bottlenecks at the ports (e.g. terminals, inland seaport<br />

traffic) can result in waiting times for container ships as could<br />

often be observed, for instance, on the east coast of the US<br />

before the crisis. Insufficient <strong>shipping</strong> depths also act as a brake<br />

on the sector’s growth. The growing importance of very large<br />

container ships makes a deepening of the waterways/<strong>shipping</strong><br />

lanes necessary at many ports (e.g. in Hamburg). The expansion<br />

5 The short support period does admittedly limit the meaningfulness of the model.<br />

The relevant test statistics are admittedly good and are accompanied by the<br />

respectively “right” sign. The confidence interval is, however, comparatively wide<br />

because of the small number of variables.<br />

March 28, 2011 7

Oil becoming more<br />

expensive<br />

USD<br />

140<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10<br />

Oil price, USD per barrel*, left<br />

Heavy oil, USD per tonne, right<br />

* Monthly average prices for Brent, Dubai and WTI<br />

crude<br />

700<br />

600<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

Sources: HWWI, WEFA 18<br />

Current Issues<br />

of the port infrastructure required by the transport industry often<br />

flounders because of financial limitations or political resistance.<br />

— Fuel and lubricant prices will continue rising, because demand<br />

for oil tends to rise faster than supply.<br />

— During the global recession protectionist ideas experienced a<br />

renaissance in many countries. The danger that the liberalisation<br />

of global trade becomes mired permanently is at least no lower<br />

now than before the crisis.<br />

— The rising number of pirate attacks in several maritime regions<br />

means higher costs for ship owners, for instance for insurance or<br />

for modifying their ships (e.g. installing shelters for the crews).<br />

— The availability of qualified nautical personnel is a medium to<br />

long-term challenge for the sector; personnel costs are set to<br />

rise.<br />

All in all, the sector’s growth prospects are subject to political and<br />

economic challenges. Ultimately, however, global container <strong>shipping</strong><br />

will remain the fastest growing mode of transport over the medium<br />

term.<br />

Eric Heymann (+49 69 910-31730, eric.heymann@db.com)<br />

© Copyright 2011. <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG, DB <strong>Research</strong>, D-60262 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. All rights reserved. When quoting please cite “<strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong><br />

<strong>Research</strong>”.<br />

The above information does not constitute the provision of investment, legal or tax advice. Any views expressed reflect the current views of the author, which do<br />

not necessarily correspond to the opinions of <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG or its affiliates. Opinions expressed may change without notice. Opinions expressed may differ<br />

from views set out in other documents, including research, published by <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong>. The above information is provided for informational purposes only<br />

and without any obligation, whether contractual or otherwise. No warranty or representation is made as to the correctness, completeness and accuracy of the<br />

information given or the assessments made.<br />

In Germany this information is approved and/or communicated by <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG Frankfurt, authorised by Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht.<br />

In the United Kingdom this information is approved and/or communicated by <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG London, a member of the London Stock Exchange regulated by<br />

the Financial Services Authority for the conduct of investment business in the UK. This information is distributed in Hong Kong by <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG, Hong Kong<br />

Branch, in Korea by <strong>Deutsche</strong> Securities Korea Co. and in Singapore by <strong>Deutsche</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> AG, Singapore Branch. In Japan this information is approved and/or<br />

distributed by <strong>Deutsche</strong> Securities Limited, Tokyo Branch. In Australia, retail clients should obtain a copy of a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to any<br />

financial product referred to in this report and consider the PDS before making any decision about whether to acquire the product.<br />

Printed by: HST Offsetdruck Schadt & Tetzlaff GbR, Dieburg<br />

ISSN Print: 1612-314X / ISSN Internet and e-mail: 1612-3158<br />

8 March 28, 2011