Generation XXX

Generation XXX

Generation XXX

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

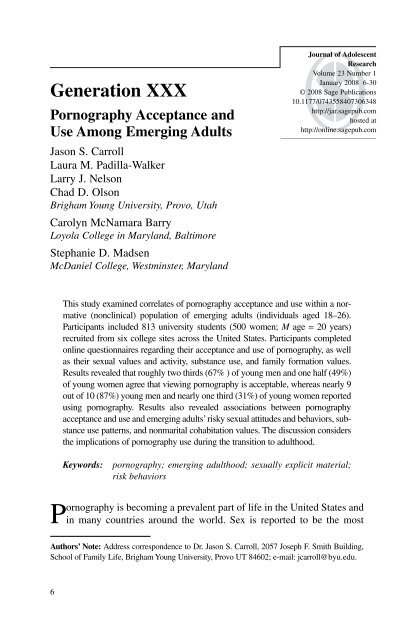

<strong>Generation</strong> <strong>XXX</strong><br />

Pornography Acceptance and<br />

Use Among Emerging Adults<br />

Jason S. Carroll<br />

Laura M. Padilla-Walker<br />

Larry J. Nelson<br />

Chad D. Olson<br />

Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah<br />

Carolyn McNamara Barry<br />

Loyola College in Maryland, Baltimore<br />

Stephanie D. Madsen<br />

McDaniel College, Westminster, Maryland<br />

Journal of Adolescent<br />

Research<br />

Volume 23 Number 1<br />

January 2008 6-30<br />

© 2008 Sage Publications<br />

10.1177/0743558407306348<br />

http://jar.sagepub.com<br />

hosted at<br />

http://online.sagepub.com<br />

This study examined correlates of pornography acceptance and use within a normative<br />

(nonclinical) population of emerging adults (individuals aged 18–26).<br />

Participants included 813 university students (500 women; M age = 20 years)<br />

recruited from six college sites across the United States. Participants completed<br />

online questionnaires regarding their acceptance and use of pornography, as well<br />

as their sexual values and activity, substance use, and family formation values.<br />

Results revealed that roughly two thirds (67% ) of young men and one half (49%)<br />

of young women agree that viewing pornography is acceptable, whereas nearly 9<br />

out of 10 (87%) young men and nearly one third (31%) of young women reported<br />

using pornography. Results also revealed associations between pornography<br />

acceptance and use and emerging adults’risky sexual attitudes and behaviors, substance<br />

use patterns, and nonmarital cohabitation values. The discussion considers<br />

the implications of pornography use during the transition to adulthood.<br />

Keywords: pornography; emerging adulthood; sexually explicit material;<br />

risk behaviors<br />

Pornography is becoming a prevalent part of life in the United States and<br />

in many countries around the world. Sex is reported to be the most<br />

Authors’ Note: Address correspondence to Dr. Jason S. Carroll, 2057 Joseph F. Smith Building,<br />

School of Family Life, Brigham Young University, Provo UT 84602; e-mail: jcarroll@byu.edu.<br />

6

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 7<br />

frequently searched topic on the Internet (Cooper, Delmonico, & Burg,<br />

2000), with pornographic search-engine requests totaling approximately 68<br />

million per day (25% of total search-engine requests). Although exact<br />

figures are difficult to ascertain, recent reports estimate that approximately<br />

40 million adults in the United States regularly visit Internet pornography<br />

sites; in terms of economic impact, the pornography industry annually generates<br />

an estimated $100 billion dollars worldwide, with over $13 billion in<br />

revenue from the United States (Ropelato, 2007).<br />

The proliferation of pornography in the current lives of Americans is<br />

undoubtedly linked to the changing technological context of modern<br />

society. The extensive availability of personal computers (beginning in<br />

1982–1985), the subsequent widespread access to the Internet (beginning in<br />

1995), and the advent of pay-per-view home movies (beginning in 1990–1995)<br />

have changed the technological context for accessing pornography (Buzzell,<br />

2005a). Cooper and colleagues (2000) suggest that these technological<br />

advances have created a “triple-A engine” that fuels an increased trend of<br />

pornography consumption, referring to the increased accessibility (millions<br />

of pornographic websites are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week), affordability<br />

(competition on the Internet keeps prices low, and there are a host of<br />

ways to get free pornography), and anonymity of sexually explicit materials<br />

(in the privacy of one’s own home, people perceive their accessing of pornography<br />

to be anonymous). These technological changes make questions about<br />

pornography particularly relevant to young people, who are coming of age in<br />

a context where computers and Internet access are ubiquitous in households<br />

and college campuses across America. Emerging adulthood (18–25 years)<br />

may be a time of particular interest because it is a period that is characterized<br />

by exploration in the areas of sexuality, romantic relationships, identity, and<br />

values, as well increased participation in risk behaviors (Arnett, 2006).<br />

Despite the documented increase of pornography during the last decade<br />

and its near-mainstream status in American culture, little attention has been<br />

given to the topic in leading research journals. For example, a targeted database<br />

search (using the PsychInfo database) of the top five adolescent journals,<br />

the top five developmental journals, and the top five family journals since 1995<br />

reveals that only one article has been published reporting on a study where<br />

pornography was a primary focus (Cameron et al., 2005) and only two articles<br />

where pornography was investigated as an issue of minor or secondary interest<br />

(Wang, Bianchi, & Raley, 2005; Young-Ho, 2001). Given this lack of attention<br />

in leading journals, little is known about the correlates and outcomes of<br />

pornography use in regard to individual development and family formation<br />

patterns. There is a growing literature on pornography in specialty journals

8 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

that address sexuality and the clinical treatment of sexual disorders, but<br />

these studies typically utilize nonnormative samples and rarely address core<br />

developmental processes and outcomes.<br />

For this project, pornography was defined as media used or intended to<br />

increase sexual arousal. Such material generally portrays images of nudity and<br />

depictions of sexual behaviors. Researchers have labeled this class of media<br />

using terms such as sexually explicit materials (Goodson, McCormick, & Evans,<br />

2001), erotica (Zillmann, 1994), and online sexual activity (Cooper et al., 2000).<br />

The purpose of this study was to examine levels of pornography use and<br />

acceptance among a normative sample of emerging adults (aged 18 to 26) in<br />

the United States and to compare usage rates across age cohorts within this<br />

developmental period. Analyses were conducted to investigate how patterns of<br />

pornography acceptance and use were associated with emerging adults’ sexual<br />

attitudes and behaviors, substance use patterns, and family formation values.<br />

These dependent variables were selected to investigate issues of importance to<br />

current functioning during emerging adulthood and future family formation.<br />

Pornography Literature<br />

A review of the scholarly research addressing pornography reveals a<br />

diverse literature that spans nearly 50 years. However, much of this literature<br />

is dated, in that it predates the current technological context of pornography<br />

(Buzzell, 2005a). Also, much of the existing literature is of limited<br />

use for our purposes here because it focuses on issues related to criminology<br />

and the clinical treatment of sexual compulsions rather than use among<br />

normative populations. Beginning as early as the 1970s and 1980s, scholars<br />

have investigated potential links between pornography and criminal<br />

behaviors such as violence and aggression (Allen, D’Alessio, & Brezgel,<br />

1995), sexual offenses (Bauserman, 1996), and child pornography (Quayle<br />

& Taylor, 2003). Although meta-analytic studies have frequently documented<br />

a link between pornography exposure and increased criminal and<br />

deviant behavior (Allen et al., 1995; Oddone-Paolucci, Genuis, & Violato,<br />

2000), inconsistent findings and limitations in the research have created<br />

divergent perspectives and an ongoing debate among scholars about the<br />

effects of pornography exposure on the subsequent behavior of individuals.<br />

Clinical research on pornography has increased in recent years as mental<br />

health professionals across disciplines have reported a marked increase<br />

in the number of clients seeking treatment for sexually addictive problems<br />

related to pornography (Mitchell, Becker-Blease, & Finkelhor, 2005).

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 9<br />

Using clinical samples, this line of research has begun to identify potential links<br />

between pornography compulsion and individual problems (Philaretou,<br />

Mahfouz, & Allen, 2005) and potential couple dynamics (R. M. Bergner &<br />

Bridges, 2002). Although criminal and clinical research studies examine a<br />

number of unique questions, they are typically based on nonnormative<br />

samples with existing disorders and are fairly limited in scope, in that they<br />

address only extremes of pornography addiction, psychopathology, and<br />

criminal behavior. We focus our review here on research that has been done<br />

with normative samples and that addresses correlates and outcomes of<br />

pornography use and acceptance among emerging adults.<br />

A small number of studies have examined pornography use in the general<br />

population (Cooper, Delmonico, Griffin-Shelly, & Mathy, 2004; Cooper et al.,<br />

2000; Cooper, Galbreath, & Becker, 2004; Cooper, Putnam, Planchon, &<br />

Boies, 1999) and have found that pornography use is highest among individuals<br />

aged 18–25 (Buzzell, 2005b). Research conducted to date suggests that<br />

approximately 50% of college students report viewing pornography on the<br />

Internet (Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2001). Goodson and colleagues (2001)<br />

examined Internet pornography use among 506 college students and found<br />

that 56% of men and 35% of women reported using the Internet for sex-related<br />

information. Boies (2002) examined Internet pornography use among 1,100<br />

university students and found that 72% of men and 24% of women reported<br />

using the Internet to view pornography, with 11% of users viewing sexually<br />

explicit materials once a week or more. Furthermore, those who reported<br />

greater exposure to pornography were more likely to be sexually experienced,<br />

report lower sexual anxiety, and have a higher number of sexual partners<br />

(Morrison, Harriman, Morrison, Bearden, & Ellis, 2004).<br />

In addressing the question of what motivates college students to participate<br />

in pornography use on the Internet, Goodson et al. (2001) found that<br />

30% of users reported accessing sexually explicit materials on the Internet<br />

out of curiosity, 19% to become sexually aroused, and 13% as a means of<br />

enhancing their offline sexual encounters. Boies (2002) found that a majority<br />

(82%) reported that viewing sexually explicit material online was sexually<br />

arousing, 40% reported that it satisfied curiosity, and 63% reported that<br />

they learned new sexual techniques. Although there is a disparity between<br />

the primary motivations for pornography use between these two studies, it<br />

is clear that becoming sexually aroused and fulfilling curiosity are salient<br />

motivations for Internet pornography use among emerging adults. Research<br />

also suggests that emerging adults’ use of sexually explicit materials online<br />

is primarily a solitary activity, with 35% of users reporting the use of<br />

Internet pornography while alone, 18% with offline partners, and 15% in a

10 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

group context (Goodson et al., 2001). This finding is further supported by<br />

research suggesting that 83% of young men and 55% of young women<br />

reported masturbating while viewing pornography (Boies, 2002).<br />

Although men of all ages overwhelmingly report greater pornography<br />

use than do women, Boies (2002) found that in younger samples, women<br />

viewed pornographic material at a higher proportion to males (3:1) than in<br />

older samples (6:1). Furthermore, Goodson et al. (2001) examined the emotional<br />

correlates of pornography use among college students and found few<br />

gender differences in reports of arousal in response to sexually explicit<br />

materials. Goodson and colleagues suggested that the use of sexually<br />

explicit material on the Internet is a valued activity for women and provides<br />

a safe medium through which women can explore their sexuality.<br />

Focus of the Study<br />

Existing studies provide some insight into the pornography patterns of<br />

emerging adults and some of the reasons behind their use of pornography,<br />

but there continue to be unanswered questions regarding how pornography<br />

might be associated with salient developmental features of emerging adulthood.<br />

For example, there is little research examining correlates of pornography<br />

use with variables other than sexual attitudes and behaviors, such as<br />

substance use and family formation values. Given that emerging adults<br />

appear to be using pornography as much or more than any other age group<br />

and may also have more aspects of their lives in transition than do other age<br />

groups (Arnett, 2006), it is important to understand how pornography use<br />

during this developmental period might be related to other values and<br />

behaviors that are important for positive development.<br />

This study was designed to examine how pornography use and acceptance<br />

are associated with emerging adults’ sexual attitudes and behaviors, substance<br />

use patterns, and family formation values. Dependent variables were selected<br />

to investigate issues of importance to current functioning during emerging<br />

adulthood and future family formation. For example, family scholars have<br />

found certain premarital behaviors, such as permissive sexuality (Heaton,<br />

2002; Kahn & London, 1991; Larson & Holman, 1994; Teachman, 2003)<br />

and nonmarital cohabitation (DeMaris & Rao, 1992; Dush, Cohan, &<br />

Amato, 2003; Kline et al., 2004), to be associated with less marital stability<br />

in future marriages. Conversely, sexuality (Lefkowitz & Gillen, 2006)<br />

and substance use patterns (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006) are more<br />

commonly examined arenas of exploration and experimentation during

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 11<br />

emerging adulthood. This study was designed to address two primary<br />

research questions:<br />

Question 1: What are the levels of acceptance and use of pornography among<br />

emerging adults, and how do these patterns vary across age cohorts within this<br />

developmental period?<br />

Question 2: To what extent are levels of pornography acceptance and use associated<br />

with sexuality, substance use, and family formation patterns in emerging adulthood?<br />

Furthermore, this study was designed to address five limitations that<br />

exist in pornography research to date:<br />

Limitation 1: Findings suggest that the use of one medium of media to access<br />

pornography (i.e., the Internet) is highly correlated with the use of other forms<br />

of pornography use, such as reading pornographic magazines and viewing<br />

videotapes (Goodson et al., 2001) as well as going to offline public venues to<br />

view pornographic entertainment (Boies, 2002). Thus, focusing solely on<br />

Internet pornography likely results in an underestimation of the frequency of<br />

pornography use among emerging adults, especially when considering that adolescents<br />

and emerging adults report using offline pornography more frequently<br />

than online pornography (Boies, 2002; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005). Thus, the current<br />

study examined overall pornography use across media in an attempt to<br />

obtain a more accurate understanding of the frequency of pornography use.<br />

Limitation 2: Our review of the literature revealed that results are mixed in regard<br />

to the frequency of pornography use (ranging from 40%–90%) and the correlates<br />

of this behavior among emerging adults. These inconsistencies are likely the<br />

result of (a) past researchers not examining men and women separately in their<br />

analyses and (b) their utilizing small samples, typically recruited from a single<br />

university location. In an attempt to obtain a more representative sample, data<br />

from the current study were gathered from six geographically diverse universities<br />

across the United States, and all analyses were separately computed for<br />

emerging adult men and women.<br />

Limitation 3: Scholars examining correlates of pornography use have rarely controlled<br />

for other variables that may be affecting the relationship between pornography<br />

use and other behaviors, thereby posing a threat to the validity of the<br />

findings and to the inferences made from them. For example, although scholars<br />

have explored links between religiosity and pornography use (Goodson,<br />

McCormick, & Evans, 2000), studies rarely control for religiosity when investigating<br />

the affects of pornography. Without these control variables, scholars<br />

cannot rule out plausible alternative explanations for their findings. Controlled<br />

analyses are particularly needed when examining links between pornography<br />

use and risk behavior or sexual activity because the observed relation may be<br />

due to a third variable, such as impulsivity (see Peter & Valkenburg, 2006) or

12 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

relationship status (A. J. Bergner, Bergner, & Hesson-Mcinnis, 2003). To minimize<br />

the likelihood of identifying spurious correlations, all analyses in this study controlled<br />

for the religiosity, impulsivity, age, and relationship status of the participants.<br />

Limitation 4: Much of the existing literature on pornography use is limited in value<br />

because the researchers measured usage patterns with personally defined<br />

response codes (e.g., never, seldom, sometimes, often) rather than temporally<br />

based response codes that provide actual frequencies of use (e.g., weekly, every<br />

other day, daily). To better ascertain frequency patterns, this study measured<br />

pornography use with a temporally based response pattern.<br />

Limitation 5: Finally, many pornography studies only look at patterns of pornography<br />

use but do not simultaneously investigate rates of acceptance of pornography,<br />

whether personally used or not. Studying values related to pornography<br />

may be a critical addition to the literature, in that it allows scholars to look at<br />

how widely accepted pornography use is among certain developmental cohorts<br />

and to identify the degree to which this behavior is condoned or condemned by<br />

one’s peers. The study of values related to pornography may be particularly beneficial<br />

in the study of couple formation patterns where men’s and women’s usage<br />

patterns may differ, but acceptance or nonacceptance of a partner’s behavior may<br />

have implications for relationship dynamics and quality.<br />

Participants<br />

Method<br />

The participants for this study were selected from an ongoing study of<br />

emerging adults and their parents, entitled Project READY (Researching<br />

Emerging Adults’ Developmental Years). This project is a collaborative multisite<br />

study that is being conducted by a consortium of developmental and<br />

family scholars. The sample that was utilized in the current study consisted<br />

of 813 undergraduate and graduate students (500 women, 313 men) recruited<br />

from six college sites across the country: a small private liberal arts college<br />

and a medium-sized religious university on the East Coast, two large<br />

Midwestern public universities, a large religious university in the intermountain<br />

West, and a large public university on the West Coast. Participants ranged<br />

in age from 18 to 26, with the mean age being 20.0 years (SD = 1.84).<br />

Overall, 79% of the participants were European American, 4% were African<br />

American, 9% were Asian American, 3% were Latino American, and 5%<br />

indicated that they were “mixed/biracial” or of an other ethnicity. Furthermore,<br />

96% reported that their sexual preference was heterosexual, 2%<br />

reported a homosexual preference, and another 2% reported a bisexual preference.<br />

Study participants reported a variety of religious affiliations: Roman

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 13<br />

Catholic, 35.1%; conservative Christian, 16.6%; liberal Christian, 16.0%;<br />

Latter-day Saint (Mormon), 2.9%; other faiths (e.g., Jewish, Greek Orthodox,<br />

Muslim), 3.2%; atheist/agnostic, 7.9%; and no affiliation, 9.5%. All of the participants<br />

were unmarried (6.3% cohabiting with a partner in an intimate relationship),<br />

and 90% reported living outside their parents’ home in an<br />

apartment, house, or dormitory.<br />

Procedure<br />

Participants completed the Project READY questionnaire via the Internet<br />

(see http://www.projectready.net). The use of an online data collection protocol<br />

facilitated unified data collection across multiple university sites and<br />

allowed for the survey to be administered to emerging adults and their parents,<br />

who were living in separate locations throughout the country (parent data were<br />

not used in the current study). Participants were recruited through faculty<br />

announcement of the study in undergraduate and graduate courses. Professors<br />

at the various universities were provided with a handout to give to their<br />

students that had a brief explanation of the study, as well as directions for<br />

accessing the online survey. Interested students then accessed the study Web<br />

site with a location-specific recruitment code. Informed consent was obtained<br />

online, and only after consent was given could the participants begin the questionnaires.<br />

Each participant was asked to complete a survey battery of 448<br />

items. Sections of the survey addressed areas such as background information,<br />

family-of-origin experiences, self-perceptions, personality traits, values, risk<br />

behaviors, dating behaviors, prosocial behaviors, and religiosity. The survey<br />

also assessed attitudes and behaviors pertaining to couple formation, such as<br />

cohabitation, sexuality, and interpersonal competencies. Most participants<br />

were offered course credit or extra credit for their participation. In some cases<br />

(approximately 5%), participants were offered small monetary compensation<br />

(i.e., $10–$20 gift certificates) for their participation.<br />

Measures<br />

For the current study, we examined associations between emerging<br />

adults’ reports of their acceptance and use of pornography and their attitudes<br />

and behaviors related to potential risk behaviors (i.e., sexuality and<br />

substance use) and family formation values.<br />

Pornography acceptance and use. Two items were used to measure participants’<br />

levels of acceptance and use of pornography. Acceptance of

14 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

pornography was measured by asking respondents how much they agreed<br />

with the statement “Viewing pornographic material (such as magazines,<br />

movies, and/or Internet sites) is an acceptable way to express one’s sexuality.”<br />

Responses were recorded on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (very<br />

strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). To assess pornography use,<br />

emerging adults were asked the question, “How frequently do you view<br />

pornographic material (such as magazines, movies, and/or Internet sites)?”<br />

Responses for this item were measured on a 6-point scale ranging from 0<br />

to 5 (0 = none, 1 = once a month or less, 2 = 2 or 3 days a month, 3 = 1 or<br />

2 days a week, 4 = 3 to 5 days a week, 5 = everyday or almost everyday).<br />

Risk behaviors. Emerging adults’ sexual permissiveness was measured<br />

using a two-item scale assessing how much participants agreed or disagreed<br />

with sexual value statements on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (very<br />

strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). These statements related to<br />

their personal sexual ethics regarding premarital sexual relations (“It is all<br />

right for a man and woman to have sexual relations before marriage”) and<br />

uncommitted sexual relations (“It is all right for two people to get together<br />

for sex and not necessarily expect anything further”). Preliminary analyses<br />

found that this scale had strong internal consistency (emerging adult men,<br />

α=.84; emerging adult women, α=.84) and that, on average, emerging<br />

adult men (M = 3.92, SD = 1.36) reported higher levels of sexual permissiveness<br />

than did emerging adult women (M = 3.51, SD = 1.35).<br />

Participants’ agreement with extramarital sexuality was assessed with a single<br />

item (“It is all right for a married person to have sexual relations with<br />

someone other than his/her spouse”): emerging adult men, M = 1.36, SD =<br />

.78; emerging adult women, M = 1.22, SD = .67. Two items were used to<br />

assess participants’ sexual behavior. Open-response questions asked emerging<br />

adults to report the number of sexual partners that they have had in their<br />

lifetime (emerging adult men, M = 3.10, SD = 6.17; emerging adult women,<br />

M = 2.51, SD = 4.01) and within the last 12 months (emerging adult men,<br />

M = 1.19, SD = 1.70; emerging adult women, M = .97, SD = 1.29).<br />

Emerging adults reported their frequency of substance use using a fiveitem<br />

scale assessing alcohol consumption, binge drinking (i.e., drinking 4<br />

or 5 drinks or more in one occasion), cigarette smoking, marijuana use, and<br />

their use of other illegal drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin, crystal meth, mushrooms).<br />

Responses were reported using a 6-point scale ranging from 0 to 5<br />

(0 = none, 1 = once a month or less, 2 = 2 or 3 days a month, 3 = 1 or 2<br />

days a week, 4 = 3 to 5 days a week, 5 = everyday or almost everyday).<br />

Preliminary analyses found that this scale had good internal consistency

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 15<br />

(emerging adult men, α=.76; emerging adult women, α=.76) and that, on<br />

average, emerging adult men (M = 1.19, SD = .96) reported higher levels of<br />

substance use than did emerging adult women (M = .86, SD = .76).<br />

Family formation values. Emerging adults’ values regarding family formation<br />

practices were assessed in the areas of nonmarital cohabitation and childbearing,<br />

marriage ideals, and views of parenting. Participants’ endorsement of<br />

cohabitation was measured using a six-item scale measured on a 6-point scale<br />

ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Value statements<br />

included in this scale included “It is all right for a couple to live together<br />

without planning to get married,” “It is all right for an unmarried couple to live<br />

together as long as they have plans to marry,” “Living together before marriage<br />

will improve a couple’s chances of remaining happily married,” “A couple will<br />

likely be happier in their marriage if they live together first,” “It is a good idea<br />

for a couple to live together before getting married as a way of ‘trying out’ their<br />

relationship,” and “Living together first is a good way of testing how workable<br />

a couple’s marriage would be.” Preliminary analyses found that this scale had<br />

very strong internal consistency (emerging adult men, α=.94; emerging adult<br />

women, α=.93) and that, on average, emerging adult men (M = 3.75, SD =<br />

1.21) reported higher levels of endorsement of cohabitation than did emerging<br />

adult women (M = 3.39, SD = 1.17). Participant’s agreement with out-of-wedlock<br />

childbirth was assessed with a single item (“I would personally consider<br />

having a child out-of-wedlock”) measured on a 6-point scale ranging from 1<br />

(very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Preliminary analyses found<br />

that, on average, emerging adult men (M = 2.24, SD = 1.23) and women (M =<br />

2.13, SD = 1.20) hold similar views on this approach to family formation.<br />

Carroll and colleagues (2007) have proposed that emerging adults develop<br />

a marital horizon, or marriage philosophy, that comprises at least three interconnected<br />

factors—marital importance, desired marital timing, and criteria for<br />

marriage readiness. Three items measured on a 6-point scale ranging from 1<br />

(very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree) were used to measure participants’<br />

ideals for marriage in these three domains. One measured participants’<br />

agreement to value statements regarding marital importance (“Being<br />

married is a very important goal for me”), emerging adult men, M = 3.77,<br />

SD = 1.31; emerging adult women, M = 3.44, SD = 1.35. The next assessed<br />

participant’s desired age for marriage (“What is the ideal age (in years) for an<br />

individual to get married?”), emerging adult men, M = 25.4 years old, SD =<br />

2.12; emerging adult women, M = 24.8 years old, SD = 1.83. A third item<br />

assessed desires for spousal independence in marital finances (“In marriage,<br />

it is a good idea for each spouse to maintain control over his/her personal

16 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

finances”), emerging adult men, M = 3.78, SD = 1.36; emerging adult<br />

women, M = 3.65, SD = 1.35. A three-item scale using the agreement<br />

responses mentioned previously was used to measure participants’ degree<br />

of child-centeredness, or positive appraisal of becoming a parent in the<br />

future. The three items were “Having children is a very important goal for<br />

me,” “Being a father and raising children is one of the most fulfilling experiences<br />

a man can have,” and “Being a mother and raising children is one<br />

of the most fulfilling experiences a woman can have.” Preliminary analyses<br />

found that this scale had strong internal consistency (emerging adult men,<br />

α=.86; emerging adult women, α=.84) and that, on average, emerging<br />

adult men (M = 4.83, SD = 1.08) and emerging adult women (M = 4.89,<br />

SD = .91) had similarly high levels of child-centeredness.<br />

Results<br />

The analyses for this study were conducted in a sequential format to test<br />

the two research questions detailed previously. Because of historical gender<br />

differences in the several variables measured—including average median<br />

age at marriage, sexual behaviors, and substance use—analyses were run<br />

separately for emerging adult men and women.<br />

Question 1: What are the levels of acceptance and use of pornography among<br />

emerging adults, and how do these patterns vary across age cohorts within this<br />

developmental period?<br />

Frequency levels of emerging adults’ acceptance and use of pornography<br />

were calculated for men and women (see Table 1). These analyses revealed<br />

that emerging adult men accepted and used pornography more frequently<br />

than did emerging adult women, although these differences were more pronounced<br />

in usage patterns. Two thirds (66.5%) of emerging adult men<br />

reported that they agreed, at some level, that viewing pornography is<br />

acceptable, whereas emerging adult women were evenly split (48.7% agree,<br />

51.3% disagree) on whether viewing pornography was an acceptable way<br />

to express one’s sexuality. With regard to actual usage rates of pornography,<br />

87% of emerging adult men reported using pornography at some level, with<br />

approximately one fifth reporting daily or every-other-day use (i.e., 3 to 5<br />

times a week) and nearly half (48.4%) reporting a weekly or more frequent<br />

use pattern. Women’s usage patterns were markedly different, with about<br />

one third (31%) reporting pornography use at some level. However, the

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 17<br />

majority of emerging adult women using pornography reported a once a<br />

month or less pattern of usage, and only 3.2% of women reported a use pattern<br />

of weekly or more. An intriguing pattern surfaced when the data on<br />

pornography acceptance were transposed on emerging adults’ reported<br />

usage rates of pornography. For emerging adult men, approximately 1 in 5<br />

reported that they used pornography but did not believe that it is an acceptable<br />

behavior, whereas among emerging adult women, approximately 1 in<br />

5 reported that pornography is acceptable, but they did not personally use<br />

pornography.<br />

In the absence of longitudinal data, the best way to ascertain if pornography<br />

usage and acceptance rates vary across emerging adulthood is to compare<br />

usage rates across age cohorts within the developmental period. As such, our<br />

sample was divided into three age cohorts (18- and 19-year-olds, n = 397; 20to<br />

22-year-olds, n = 337; and 23- to 26-year-olds, n = 79), and MANCOVA<br />

(multiple analysis of covariance) comparisons were computed on emerging<br />

adult men’s and women’s usage and acceptance rates of pornography. Because<br />

previous research has found that risk behaviors typically peak at about age 22<br />

(Arnett, 2006; Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006), we included a measure of binge<br />

drinking (i.e., the item from the Substance Use Scale) in these age comparisons<br />

to investigate if pornography use followed a similar pattern.<br />

These analyses revealed that for emerging adult men, there were significant<br />

differences between the age cohorts on binge-drinking rates but not on<br />

pornography use or acceptance (MANCOVA: emerging adult men, F = 3.50,<br />

df = 3, p < .05). In particular, emerging adult men followed the expected<br />

pattern, with men aged 23 to 26 reporting significantly less (p < .01) binge<br />

drinking (M = 1.21, SD = 1.26) than their younger counterparts (18- and 19year-olds,<br />

M = 1.84, SD = 1.47; 20- to 22-year-olds, M = 1.86, SD = 1.42).<br />

Although slight declines in pornography use and acceptance were found for<br />

men aged 23 to 26, these differences did not reach statistical significance.<br />

Emerging adult women followed a similar pattern (MANCOVA: emerging<br />

adult women, F = 5.08, df = 3, p < .01), with older emerging adults reporting<br />

significantly less (p < .01) binge drinking behavior (23- to 26-year-olds, M =<br />

1.07, SD = 1.10) than younger women (18- and 19-year-olds, M = 1.37, SD =<br />

1.31; 20- to 22-year-olds, M = 1.32, SD = 1.28); however, pornography use<br />

patterns remained steady across the three groups, and a significant increase<br />

(p < .01) in the acceptance of pornography was identified between women<br />

aged 23 to 26 (M = 3.63, SD = 1.20) and women aged 18 or 19 (M = 3.05,<br />

SD = 1.29). It is interesting to note that although gender differences in pornography<br />

use remain consistent across the three age cohorts, increases in the<br />

acceptance of pornography among older emerging adult women place men’s

18 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

Table 1<br />

Acceptance and Use of Pornography Among<br />

Emerging Adults (in Percentages)<br />

Emerging Adult Emerging Adult<br />

Men (n = 313) Women (n = 500)<br />

Pornography acceptance a<br />

Very strongly disagree 8.0 14.5<br />

Strongly disagree 7.4 11.3<br />

Disagree 18.0 25.5<br />

Agree 45.3 39.0<br />

Strongly agree 9.6 6.3<br />

Very strongly agree 11.6 3.4<br />

Pornography use b<br />

None 13.9 69.0<br />

Once a month or less 16.8 20.7<br />

2 or 3 days a month 21.0 7.1<br />

1 or 2 days a week 27.1 2.2<br />

3 to 5 days a week 16.1 .8<br />

Everyday or almost every day 5.2 .2<br />

a. “Viewing pornographic material (such as magazines, movies, and/or Internet sites) is an<br />

acceptable way to express one’s sexuality.”<br />

b. “During the past 12 months, on how many days did you view pornographic material (such<br />

as magazines, movies, and/or Internet sites)?”<br />

and women’s acceptance of pornography at the same level by the time that<br />

they reach their mid twenties.<br />

Question 2: To what extent are levels of pornography acceptance and use associated with<br />

sexuality, substance use, and family formation patterns in emerging adulthood?<br />

Three types of analyses were used to investigate the study’s second<br />

research question. First, partial correlations were calculated to determine<br />

the direction and strength of the associations between the pornography<br />

items and the other study variables. Next, to examine specifically how<br />

pornography use was related to salient features of emerging adulthood, we<br />

ran a series of group comparison analyses. For emerging adult men, we ran<br />

a series of MANCOVAs with five pornography use groups: Group A, never<br />

use (none); Group B, seldom use (once a month or less); Group C, monthly<br />

use (2 or 3 days a month); Group D, weekly use (1 or 2 days a week); and<br />

Group E, daily use (3 to 5 days a week or everyday or almost everyday).<br />

Because of the relatively low usage rates among women, we ran ANOVA

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 19<br />

Table 2<br />

Correlations Between Pornography Variables and Control Variables<br />

Emerging Adult Emerging Adult<br />

Men (n = 313) Women (n = 500)<br />

Pornography Pornography Pornography Pornography<br />

Control Variables acceptance use acceptance use<br />

Age .02 .06 .13 ** .08<br />

Current dating status a .01 –.02 .11 ** .18 ***<br />

Religiosity b –.39 *** –.30 *** –.44 *** –.20 ***<br />

Impulsivity c .22 *** –.19 *** .06 .04<br />

a. Current dating status: 1 = not dating at all, 2 = casual/occasional dating, 3 = have a<br />

boy/girlfriend (in an exclusive relationship), 4 = engaged, or committed to marry.<br />

b. Religiosity (“My religious faith is extremely important to me”): 1 = very strongly disagree,<br />

2 = strongly disagree, 3 = disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree, 6 = very strongly disagree.<br />

c. Impulsivity (two-item scale; emerging adult men, α=.77; emerging adult women, α=.68;<br />

“Fight with others/lose temper,” “Easily irritated or mad”): 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes,<br />

4 = often, 5 = very often.<br />

** p < .01. *** p < .001.<br />

comparisons between two groups: nonusers (Group A) and users (Group B)<br />

of pornography. We also calculated subgroup frequencies on the behavior<br />

items to further examine patterns of sexuality and substance use. Preliminary<br />

analyses revealed that age, current dating status, religiosity, and impulsivity<br />

were all correlated to some degree with pornography use and acceptance,<br />

with religiosity and impulsivity related to men’s pornography patterns and<br />

with religiosity, current dating status, and age related to women’s pornography<br />

patterns (see Table 2). To increase confidence that the associations<br />

identified between study variables were related to study hypotheses and not<br />

due to spurious correlations, we included items measuring age, current dating<br />

status, religiosity, and impulsivity as control variables in all partial correlation<br />

and group comparison analyses.<br />

Risk behaviors. As noted in Table 3, pornography use was found to be<br />

significantly related with emerging adult men’s sexual values and behaviors.<br />

Partial correlation analyses revealed a small but significant connection<br />

between pornography use and number of lifetime sexual partners among<br />

emerging adult men and their acceptance of extramarital sexual behavior.<br />

Also, the more that men accepted and used pornography, the more likely<br />

they were to be accepting of premarital and casual sexual behavior. Group<br />

comparisons revealed that the most distinctive sexual values were found

Table 3<br />

Correlations and Group Comparisons Between Pornography Variables and Emerging Adult Factors<br />

20<br />

Emerging Adult Men (n = 313) Emerging Adult Women (n = 500)<br />

Pornography Use Pornography Use<br />

None Seldom Monthly Weekly Daily No Yes<br />

Accept (r) Use (r) (= a) (= b) (= c) (= d) (= e) Accept (r) Use (r) (= a) (= b)<br />

Sexual values<br />

Sexual permissiveness .61*** .34*** 2.64bcde 3.59ade 3.92ae 4.23ab 4.68abc .55*** .15** 3.23b 4.12a Extramarital sexuality .08 .15** 1.07e 1.27 1.34 1.50 1.45a .13** .05 1.20 1.24<br />

Sexual behavior: With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse?<br />

“With how many . . .” .09 .11* 1.30e 2.37e 4.25 1.96 5.28ab .19*** .17*** 1.89b 3.75a None 58.1% 28.8 23.1 41.7 22.7 46.4 22.9<br />

3 or more partners 9.3% 25.0 33.4 25.0 40.9 26.9 46.4<br />

With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months?<br />

“With how many . . .” .02 .06 .63ce 1.04 1.14 1.26 .15 .22*** .09* .85b 1.22a None 67.4% 30.8 27.7 46.4 28.8 50.6 24.2<br />

3 or more partners 2.3% 9.6 15.4 9.5 22.7 7.7 11.1<br />

Substance use<br />

Substance Use Scale .15* .20*** .35bcde 1.14a 1.42a 1.30a 1.38a .28*** .16*** .77b 1.08a Alcohol use<br />

None 51.2% 19.2 3.1 13.1 7.6 22.4 8.5<br />

Weekly or more 18.6% 46.2 69.2 60.7 60.6 38.8 47.1<br />

Binge drinking<br />

None 69.8% 26.9 15.4 27.4 22.7 46.2 24.8<br />

Weekly or more 11.6% 32.7 49.2 46.4 51.5 22.9 29.4<br />

Note: Controlling for age, dating status, religiosity, and impulsivity. Alphabetic superscripts indicate significant group mean differences at the p < .05 level.<br />

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 21<br />

among the emerging adult men who never used pornography and reported<br />

markedly more conservative sexual values than their pornography using<br />

peers and among men who used pornography on a daily basis who reported<br />

the most liberal sexual values (MANCOVA: emerging adult men, F = 5.99,<br />

df = 5, p < .001). The daily users had, on average, nearly 5 times more lifetime<br />

sexual partners than nonusers had, and the majority of nonusers<br />

reported that they had not had sexual intercourse. Among emerging adult<br />

women, pornography acceptance and use were found to be related to sexual<br />

values and sexual behaviors, with pornography acceptance being a stronger<br />

correlate of these variables than actual pornography use. Significant group<br />

differences were found on all sexual variables (p < .001) except agreement<br />

with extramarital sexual behavior. Emerging adult women who accepted<br />

and used pornography were found to have significantly higher levels of<br />

acceptance of casual sexual behavior and to report higher numbers of<br />

sexual partners within the last 12 months and across their lifetimes.<br />

As noted in Table 3, pornography use and acceptance were also found to<br />

be significantly correlated with emerging adults’ substance use patterns.<br />

Specifically, pornography acceptance and use were correlated significantly<br />

with men’s substance use patterns. Comparisons of subgroup frequencies<br />

revealed that emerging adult men who did not use pornography had<br />

markedly lower levels of drinking and binge drinking than did their counterparts,<br />

who used pornography on a regular basis. Similar but more pronounced<br />

patterns were found among emerging adult women, among whom,<br />

pornography use and acceptance were found to be significantly correlated<br />

with higher substance use. Group comparisons documented that these differences<br />

were statistically significant (p < .01) between emerging adult<br />

women who used pornography and those who did not.<br />

Family formation values. As noted in Table 4, pornography acceptance<br />

was found to be significantly related to young people’s values and approaches<br />

to family formation; however, pornography use patterns had little correlation<br />

with these variables. Emerging adult men and women who were more<br />

accepting of pornography were also more accepting of nonmarital cohabitation,<br />

but only women who accepted pornography were found to be more<br />

likely to consider having a child out of wedlock. No correlations were<br />

found between pornography acceptance and emerging adult men’s and<br />

women’s goals for marriage. However, acceptance of pornography was<br />

found to be significantly correlated with desires for later marriage, financial<br />

independence between spouses within marriage, and lower levels of<br />

child-centeredness for emerging adult men and women. Similar to the

22<br />

Table 4<br />

Correlations and Group Comparisons Between Pornography Variables and Family Formation Values<br />

Emerging Adult Men (n = 313) Emerging Adult Women (n = 500)<br />

Pornography Use Pornography Use<br />

None Seldom Monthly Weekly Daily No Yes<br />

Accept (r) Use (r) (= a) (= b) (= c) (= d) (= e) Accept (r) Use (r) (= a) (= b)<br />

Nonmarital cohabitation and childbearing<br />

Endorsement of .41*** .11 3.11de 3.45d 3.70 4.13ab 4.08a .37*** .04 3.24b 3.71a cohabitation<br />

Out-of-wedlock childbirth .07 .06 1.82 e 2.27 2.19 2.33 2.45a .21*** .05 1.99b 2.42a Marriage and parenting<br />

“Being married is a very .06 –.02 5.08 4.76 4.86 4.52 4.49 –.08 –.03 4.96 4.93<br />

important goal for me.”<br />

Ideal age for marriage .15** .09 24.8e 25.0 25.3 26.0a 25.7 .13** .08 24.7 b 25.1a (in years)<br />

Spousal independence .17*** .03 3.58 3.51 3.70 3.76 3.66 .14*** .01 3.73 3.81<br />

Child-centeredness –.15** .01 5.01 4.86 4.87 4.84 4.81 –.13** –.06 4.97b 4.72a Note: Controlling for age, dating status, religiosity, and impulsivity. Alphabetic superscripts indicate significant group mean differences at the<br />

p < .05 level.<br />

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 23<br />

analyses involving the sexuality and substance use variables, group comparison<br />

analyses revealed that much of the variance in these correlations<br />

was attributed to the more traditional views of nonpornography using men<br />

(MANCOVA: F = 6.20, df = 6, p < .001) and women (four of six comparisons,<br />

p < .001) and their peers who used pornography.<br />

Discussion<br />

The current study examined levels of pornography use and acceptance<br />

among emerging adults in the United States. Comparisons were made<br />

between early (18- and 19-year-olds), middle (20- to 22-year-olds), and late<br />

emerging adults (23- to 26-year-olds). Additional analyses were conducted<br />

to see if patterns of pornography acceptance and use were correlated with<br />

sexual attitudes and behaviors, substance use patterns, and family formation<br />

values among emerging adults. Results suggest that pornography is a<br />

prominent feature of the current emerging adulthood culture. Pornography<br />

use was particularly prevalent among emerging adult men, with nearly half<br />

reporting that they viewed pornography at least weekly and about 1 in 5<br />

reporting that they used pornography daily or every other day. In contrast,<br />

emerging adult women were less accepting and much less likely to use<br />

pornography on a frequent basis. Given the lack of attention to pornography<br />

habits in the leading developmental, adolescent, and family journals,<br />

these findings raise a number of questions for scholars about how intentional<br />

exposure to sexually explicit material may influence the developmental<br />

patterns of the rising generation in the United States. We organize<br />

our discussion of these findings around gender differences in pornography<br />

patterns, perspectives on pornography as young people transition in and out<br />

of emerging adulthood, and considerations of how pornography may influence<br />

couple formation during and after emerging adulthood.<br />

Gender Differences in Pornography Patterns<br />

Perhaps the most notable finding of this study was the marked difference<br />

in pornography use and acceptance among emerging adult men and emerging<br />

adult women in our sample. These results suggest that pornography use<br />

is as common as drinking is among college-age men. It also appears that a<br />

sizable number of emerging adult men “binge” on pornography, with a similar<br />

frequency and intensity that define binge drinking on American college<br />

campuses. In fact, the comparison between pornography use and binge

24 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

drinking may be justified, in that pornography use was found to be moderately<br />

correlated with emerging adult men’s frequency of alcohol consumption<br />

and their rates of binge drinking, even after controlling for a number of<br />

variables that may be thought to contribute to both of these behaviors (e.g.,<br />

impulsivity, religiosity). Emerging adult women were split when it came to<br />

the topic of pornography. About half of emerging adult women were<br />

accepting of pornography use among their peers, but only about 1 in 10<br />

viewed pornography with any regularity. It may be possible that the measures<br />

that were utilized in this study influenced this finding, in that they<br />

assessed visual media of pornography (Internet, magazines, movies) rather<br />

than narrative-based erotica, which may be more appealing to women.<br />

However, even with this consideration, the differences between pornography<br />

use and acceptance among emerging adult men and women form a<br />

notable finding that requires exploration in future research.<br />

Another notable finding of this study was that the acceptance of pornography<br />

was as strongly correlated with emerging adults’ attitudes and behaviors<br />

as their actual pornography use was (or more so). This finding suggests<br />

that pornography should be regarded as much as a value stance or a personal<br />

sexual ethic as it is a behavioral pattern. This may be a particularly<br />

salient finding for emerging adult women who report higher levels of<br />

acceptance than actual use of pornography. Furthermore, pornography<br />

acceptance among women was a stronger correlate with permissive sexuality,<br />

alcohol use, binge drinking, and cigarette smoking than was actual<br />

pornography use. For men, the acceptance of pornography was more highly<br />

correlated with their sexual attitudes and family formation values than was<br />

pornography use. These findings highlight that scholars need to define<br />

pornography in terms of both values and behavior.<br />

Transitions in and out of Emerging Adulthood<br />

In addition to examining the overall usage rates of pornography among<br />

emerging adults, subanalyses were also run to determine if rates of pornography<br />

use differed significantly for early, middle, and late emerging adults.<br />

These analyses identified that the rates of pornography use were relatively<br />

stable across emerging adulthood. These patterns also suggest that pornography<br />

patterns are established during adolescence or are rapidly developed<br />

in emerging adulthood. The much lower levels of reported pornography use<br />

among adolescents (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005) suggest that the latter explanation<br />

is more plausible, but future research is needed to confirm this possibility.<br />

The age pattern found in the current study is notable because it

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 25<br />

varies from the identified pattern of exploratory behaviors during emerging<br />

adulthood, which finds that for the majority of the population, most of these<br />

types of behaviors peak at about age 22 and then decrease from that time forward<br />

(Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006). Thus, pornography use may be largely a<br />

personal pattern that is not as contingent on the peer-centered experimental<br />

context of emerging adulthood as drinking may be. This possibility is supported<br />

by research suggesting that pornography use is largely a solitary activity<br />

(Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2001), and it suggests that the solitary nature<br />

of pornography use may distinguish it from other exploratory behaviors that<br />

are common during emerging adulthood. The solitary pattern of pornography<br />

use may contribute to its being more frequently carried over into young adulthood<br />

than peer-centered experimental behaviors.<br />

A better understanding of how the transition from emerging adulthood<br />

to young adult life influences and is influenced by pornography will help<br />

clarify these processes. A key question in this line of research will be to<br />

identify whether pornography acceptance and use rates remain similar as<br />

emerging adults get older or if they change as young people transition into<br />

adult roles and relationships. For example, our data set included responses<br />

on the pornography acceptance item from 280 fathers and 343 mothers of<br />

the emerging adults sampled for this study. A post hoc frequency analysis<br />

of these responses revealed that only 36.6% of fathers and 20.4% of mothers<br />

agreed at some level that pornography was an acceptable expression of<br />

one’s sexuality. By way of comparison, emerging adults were much more<br />

accepting of pornography than their parents were, with daughters even<br />

reporting more acceptance (48.7%) than their fathers. Longitudinal<br />

research is needed to determine if this pattern reflects a life course trajectory,<br />

with acceptance of pornography decreasing as individuals move into<br />

adulthood, or if this pattern reflects a generational difference, with the rising<br />

generation being more socialized than previous generations toward<br />

pornography across the life span.<br />

Another question that arises from the pornography usage rates identified in<br />

this study is whether there is a link between the high level of habitual use<br />

among men across emerging adulthood and the development of addictive and<br />

compulsive patterns associated with pornography use. At least two alternative<br />

trajectories seem possible. First, it is possible that the high rates of pornography<br />

use among the emerging adult men identified in this study simply<br />

reflect the explorative nature of emerging adulthood and that, similar to<br />

rates of binge drinking and other risk behaviors that peak during the early<br />

twenties (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006), pornography rates will taper off and<br />

have few lasting negative effects on development. A second possibility is that

26 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

for some young men, habitual use of pornography during adolescence and<br />

emerging adulthood will act as the genesis for future problematic behaviors.<br />

Data on binge drinking reflect this type of pattern. Although the majority<br />

of young people who engage in binge drinking during late adolescence<br />

and emerging adulthood do not continue these patterns into adult life, there<br />

is a notable minority (6%–8%) that engage in frequent binge drinking during<br />

college (Brower, 2002), which may linger through life. Cooper and colleagues<br />

(Cooper, Delmonico, et al., 2004; Cooper, Galbreath, et al., 2004)<br />

have developed a typology of pornography use that demonstrates how it<br />

might affect individuals differently. Specifically, they identify three groups<br />

of users of online sexual activity: Recreational users are those who access<br />

online sexual material out of curiosity or for entertainment purposes and are<br />

not typically seen as having problems associated with their online sexual<br />

behavior. At-risk users are those who, if it were not for the availability of<br />

the Internet, may never have developed a problem with online sexuality.<br />

Finally, sexual compulsive users who, because of a propensity for pathological<br />

sexual expression, use the Internet as one forum for their sexual<br />

activities. Therefore, there may be a population of predisposed individuals<br />

for whom early exposure to pornography can lead to compulsive<br />

sexual problems. Thus, future studies should examine links between<br />

common use during adolescence and emerging adulthood and later adult<br />

patterns, including sexual compulsion.<br />

Pornography and Couple Formation<br />

Two findings from this study are of note for research on couple formation<br />

in emerging adulthood and later adult life. First, pornography was not<br />

significantly associated with young people’s goals for marriage and parenthood.<br />

Although pornography users were found to be more accepting of<br />

nonmarital cohabitation than nonpornography users were, both groups<br />

shared a mutually high regard for eventually getting married and becoming<br />

parents. Therefore, pornography use and acceptance should be interpreted<br />

within a framework that examines how these attitudes and behaviors influence<br />

young people’s marital competence and family capacities (Carroll,<br />

Badger, & Yang, 2006). However, it should also be noted that pornography<br />

use was linked to permissive sexuality and nonmarital cohabitation, two<br />

variables that have been found to be associated with less marital stability in<br />

future marriages (Dush, Cohan & Amato, 2003; Heaton, 2002; Kline et al.,<br />

2004). Furthermore, although young people who accept and use pornography<br />

identify marriage and parenthood as important life goals, it is not

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 27<br />

known if pornography influences how young people define marriage. Men<br />

who used pornography and women who accepted pornography were significantly<br />

more likely to accept a married person’s having sexual relations<br />

with someone other than his or her spouse than were their peers who did<br />

not use or accept pornography. It may be that this finding merely reflects<br />

the fact that sexually liberal people who endorse nonmarital sexual activity<br />

are more likely to use pornography as emerging adults. However, future<br />

research should examine if pornography influences people’s views of the<br />

ethos of monogamy, which accompanies traditional views of marriage.<br />

A second finding of note relating to couple formation patterns was the<br />

identified pattern that roughly half of emerging adult women expressed a<br />

disapproving view of pornography whereas nearly 9 out of 10 emerging<br />

adult men reported using pornography to some degree, with nearly half<br />

viewing pornography on a weekly or more frequent basis. This disparity<br />

raises a number of questions about couple formation patterns between men<br />

and women. What happens to men’s and women’s pornography patterns<br />

when they enter serious romantic relationships? Do men decrease or stop<br />

their pornography use when they enter a relationship? Do men continue to<br />

use pornography but do so covertly in an effort to hide their behaviors from<br />

an unaccepting partner? Do women start or increase their use when they<br />

become romantically involved with a man who uses pornography? Does a<br />

new pattern of pornography use arise during the coupling process that shifts<br />

from individual use to couple use? The answers to these developmental<br />

questions are not well understood in the pornography literature to date. In<br />

likelihood, their answers differ from couple to couple, and the patterns that<br />

emerge likely influence future couple dynamics and outcomes.<br />

Limitations and Future Directions<br />

Despite addressing a number of limitations in existing pornography<br />

research, this study has a number of restrictions that should be considered<br />

in interpreting these results. First, the sample consists of only college<br />

students, who may not be representative of the larger population. Indeed,<br />

Cooper et al. (2000) identified college students as a group that is at risk for<br />

cybersex compulsion. However, it is not clear whether this is due to their<br />

age or status as students. Future work is needed using noncollege participants,<br />

to be confident in the generalizability of these findings. Second,<br />

despite the fact that the item assessing pornography use had a temporally<br />

based response code, future research would benefit from more detailed<br />

measurement of pornography use, assessing it separately across different

28 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

contexts (e.g., erotica, Internet pornography use, videos) to determine how<br />

different media of pornography might be differentially related to outcomes.<br />

Third, research would benefit from a more detailed examination of acceptance<br />

of pornography use. The item in the current study assessed general<br />

acceptance, but it is possible that acceptance would vary if participants<br />

responded to a temporally based response code (e.g., “Daily pornography<br />

use is an acceptable way to express one’s sexuality”). This is especially<br />

salient for women, who may perceive their own minimal use of pornography<br />

to be acceptable but who may perceive men’s much higher use as being<br />

less acceptable, particularly, use that is considered habitual. It will also be<br />

important for future research to examine acceptance in various life periods<br />

and among relationship statuses (e.g., dating, engaged, married) because<br />

acceptance of pornography may vary among single, committed, and married<br />

individuals. Finally, because of the cross-sectional nature of the current<br />

data, causal inferences could not be made. The age-related trends in the current<br />

study certainly justify the need for longitudinal data, following individuals<br />

from adolescence to emerging adulthood to later adult life. Despite<br />

these limitations, the current study provides a more complete understanding<br />

of pornography use among a normative (nonclinical) population of<br />

emerging adult college students and raises a number of important questions<br />

for future research, including the importance of examining the impact of<br />

pornography use and acceptance on current functioning during adolescence<br />

and emerging adulthood and on future couple and family formation.<br />

References<br />

Allen, M., D’Alessio, D., & Brezgel, K. (1995). A meta-analysis summarizing the effects<br />

of pornography II: Aggression after exposure. Human Communication Research, 22(2),<br />

258-283.<br />

Arnett, J. J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In<br />

J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st<br />

century (pp. 3-20). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.<br />

Bauserman, R. (1996). Sexual aggression and pornography: A review of correlation research.<br />

Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18(4), 405-427.<br />

Bergner, A. J., Bergner, R. M., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2003). Romantic partner’s use of<br />

pornography: Its significance for women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 29, 1-14.<br />

Bergner, R. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement<br />

for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex and Marital<br />

Therapy, 28, 193-206.<br />

Boies, S. C. (2002). University students’ uses of and recreations to online sexual information<br />

and entertainment: Links to online and offline sexual behavior. Canadian Journal of<br />

Human Sexuality, 11, 77-89.

Carroll et al. / Pornography and Emerging Adulthood 29<br />

Brower, A. M. (2002). Are college students alcoholics? Journal of American College Health,<br />

50, 253-255.<br />

Buzzell, T. (2005a). Demographic characteristics of persons using pornography in three technological<br />

contexts. Sexuality & Culture, 9, 28-48.<br />

Buzzell, T. (2005b). The effects of sophistication, access, and monitoring on use of pornography<br />

in three technological contexts. Deviant Behavior, 26, 109-132.<br />

Cameron, K. A., Salazar, L. F., Bernhardt, J. M., Burgess-Whitman, N., Wingood, G. M., &<br />

DiClemente, R. J. (2005). Adolescents’ experience with sex on the Web: Results from<br />

online focus groups. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 535-540.<br />

Carroll, J. S., Badger, S., & Yang, C. (2006). The ability to negotiate or the ability to love?<br />

Evaluating the developmental domains of marital competence. Journal of Family Issues,<br />

27(7), 1001-1032.<br />

Carroll, J. S., Willoughby, B., Badger, S., Nelson, L. J., Barry, C. M., & Madsen, S. (2007).<br />

So close yet so far away: The impact of varying marital horizons on emerging adulthood.<br />

Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(3), 219-247.<br />

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., & Burg, R. (2000). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives:<br />

New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 7, 5-29.<br />

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., Griffin-Shelly, E., & Mathy, R. M. (2004). Online sexual activity:<br />

An examination of potentially problematic behaviors. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity,<br />

11, 129-143.<br />

Cooper, A., Galbreath, N., & Becker, M. (2004). Sex on the Internet: Furthering our understanding of<br />

men with on line sexual problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 223-230.<br />

Cooper, A., Putnam, D. E., Planchon, L. A., & Boies, S. C. (1999). Online sexual compulsivity:<br />

Getting tangled in the net. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 6(2), 79-104.<br />

DeMaris, A., & Rao, V. (1992). Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability in the<br />

United States: A reassessment. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(1), 178-190.<br />

Dush, C. M., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. (2003). The relationship between cohabitation and marital<br />

quality and stability: Change across cohorts? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 539-549.<br />

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2000). Sex on the Internet: College students’ emotional<br />

arousal when viewing sexually explicit materials on-line. Journal of Sex Education<br />

and Therapy, 25, 252-260.<br />

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2001). Searching for sexually explicit material on<br />

the Internet: An exploratory study of college students’ behavior and attitudes. Archives of<br />

Sexual Behavior, 30, 101-117.<br />

Heaton, T. B. (2002). Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States.<br />

Journal of Family Issues, 23, 392-409.<br />

Kahn, J. R., & London, K. A. (1991). Premarital sex and the risk of divorce. Journal of<br />

Marriage and the Family, 53, 845-855.<br />

Kline, G. H., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., Olmos-Gallo, P. A., Peters, M. S., Whitton,<br />

S. W., et al. (2004). Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk<br />

for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(2), 311-318.<br />

Larson, J., & Holman, T. B. (1994). Premarital predictors of marital quality and stability.<br />

Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 43(2), 228-237.<br />

Lefkowitz, E. S., & Gillen, M. M. (2006). “Sex is just a normal part of life”: Sexuality in emerging<br />

adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in<br />

the 21st century (pp. 235-255). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.<br />

Mitchell, K. J., Becker-Blease, K. A., & Finkelhor, D. (2005). Inventory of problematic<br />

Internet experiences encountered in clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research<br />

and Practice, 36(5), 498-509.

30 Journal of Adolescent Research<br />

Morrison, T. G., Harriman, R., Morrison, M. A., Bearden, A., & Ellis, S. R. (2004). Correlates<br />

of exposure to sexually explicit material among Canadian post-secondary students.<br />

Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13, 143-156.<br />

Oddone-Paolucci, E., Genuis, M., & Violato, C. (2000). A meta-analysis of the published<br />

research on the effects of pornography. In C. Violato, E. Oddone-Paolucci, & M. Genuis<br />

(Eds.), The changing family and child development (pp. 48-59). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.<br />

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2006). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit material on<br />

the Internet. Communication Research, 33, 178-204.<br />

Philaretou, A. G., Mahfouz, A. Y., & Allen, K. R. (2005). Use of Internet pornography and<br />

men’s well-being. International Journal of Men’s Health, 4, 149-169.<br />

Quayle, E., & Taylor, M. (2003). Model of problematic Internet use in people with sexual<br />

interest in children. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(1), 93-106.<br />

Ropelato, J. (2007). Internet pornography statistics. Retrieved March 27, 2007, from<br />

http://internet-filter-review.toptenreviews.com/internet-pornography-statistics.html<br />

Schulenberg, J. E., & Zarrett, N. R. (2006). Mental health during emerging adulthood:<br />

Continuity and discontinuity in courses, causes, and functions. In J. J. Arnett & J. L.<br />

Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 135-<br />

172). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.<br />

Teachman, J. (2003). Premarital sex, premarital cohabitation and the risk of subsequent marital<br />

dissolution among women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 444-455.<br />

Wang, R., Bianchi, S. M., & Raley, S. B. (2005). Teenagers’ Internet use and family rules: A<br />

research note. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1249-1258.<br />

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2005). Exposure to Internet pornography among children and<br />

adolescents: A national survey. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8, 473-486.<br />

Young-Ho, K. (2001). Korean adolescents’ health risk behaviors and their relationships with<br />

the selected psychological constructs. Journal of Adolescence Health, 29(4), 298-306.<br />

Zillmann, D. (1994). Erotica and family values. In D. Zillmann, B. Jennings, & A. C. Huston<br />

(Eds.), Media, children, and the family: Social scientific psychodynamic, and clinical perspectives<br />

(pp. 199-213). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.<br />

Jason S. Carroll, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham<br />

Young University.<br />

Laura M. Padilla-Walker, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Family Life at<br />

Brigham Young University.<br />

Larry J. Nelson, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham<br />

Young University.<br />

Chad D. Olson, BS, is a graduate student in the Marriage and Family Therapy Program at<br />

Brigham Young University.<br />

Carolyn McNamara Barry, PhD, is an assistant professor of psychology at Loyola College<br />

in Maryland.<br />

Stephanie D. Madsen, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology at McDaniel College.