Images - IUCN

Images - IUCN

Images - IUCN

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Images</strong>:<br />

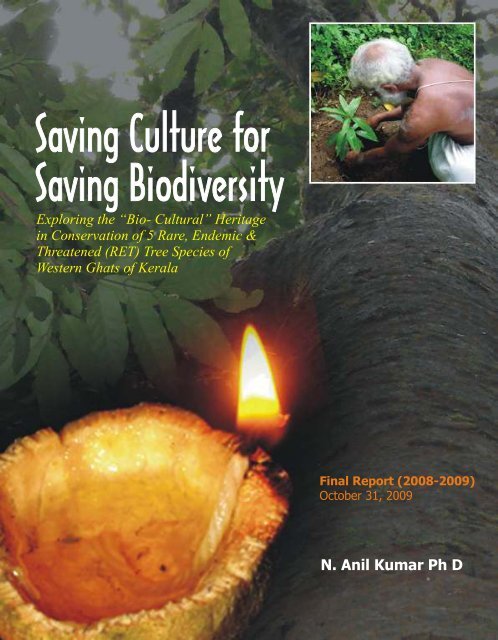

Front Cover: Backdrop: habit of Dysoxylum malabaricum, an majestic tree<br />

Traditional lamp lighted on Marotty (Hydnocarpus pentandra) fruit shell. A custom, which still<br />

followed by Hindu community<br />

A Brahmin priest planting a tree (inset)<br />

Front Inner: Seed of Wild Nutmeg (Myristica malabarica) with aril<br />

Back Inner: Leaves of Wild Cinnamon (Cinnamomum malabatrum) heaped in front of Aattukal temple<br />

Back: Fumigation with White Dammar (Vateria indica)- a normal process during holy functions.

On the occasion of planting a tree sapling of Myristica malabarica<br />

along with Shri. Jairam Ramesh, the Hon'ble Minister for Environment<br />

and Forests, Govt. Of India.<br />

Exploring the “Bio- Cultural” Heritage<br />

in Conservation of 5 Rare, Endemic &<br />

Threatened (RET) Tree Species of<br />

Western Ghats of Kerala<br />

Alcoa Foundation's<br />

Practitioner Fellowship Programme 2008<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong>, Gland<br />

Switzerland<br />

Final Report (2008-2009)<br />

October 31, 2009<br />

N. Anil Kumar Ph D<br />

M S SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION<br />

Community Agrobiodiversity Centre,<br />

Puthurvayal P.O., Kalpetta,<br />

Wayanad- 673 121, Kerala, INDIA

i<br />

01<br />

04<br />

07<br />

10<br />

12<br />

22<br />

27<br />

ii<br />

iii<br />

iv<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Summary<br />

Introduction<br />

Profile of the study site<br />

Ethnic diversity<br />

Methodology<br />

Bio-cultural value of the species studied<br />

Benefits from the study<br />

Conclusions & the steps ahead<br />

Annexures<br />

References<br />

Acronyms used

Acknowledgement<br />

I thank Alcoa Foundation and<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong> for conferring me with<br />

the Conservation Practitioner<br />

Fellowship and the support<br />

extended to carry out this study.<br />

I had detailed discussions with<br />

Dr. Jeffrey Mc Neely, Chief<br />

Scientist of <strong>IUCN</strong> and Dr.<br />

Gonzalo Oviedo, Senior<br />

Advisor for Social Policy of<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong> for finalizing the<br />

research idea and the<br />

methodology for this study. I<br />

am grateful to them for their<br />

brilliant suggestions and help.<br />

My sincere thanks are due to<br />

Prof. M. S. Swaminathan,<br />

Chairman of MSSRF for his<br />

encouragement to take up this<br />

fellowship and study. The<br />

assistance of Mr. K.G. Anish,<br />

Mr. Mithunlal, Dr. E.<br />

Unnikrishnan, Ms. Smitha, Ms.<br />

Sujana and Ms. Sreevidhya in<br />

various stages of this study and<br />

report finalisation is gratefully<br />

acknowledged here. There were<br />

several men and women from<br />

different communities shared<br />

with me their knowledge and<br />

information of the species<br />

studied under this project. I<br />

record my heartfelt thanks to all<br />

of them. Finally, few words of<br />

appreciation towards Ms. Price<br />

Wendy of <strong>IUCN</strong> and Ms.<br />

Burton Caitlin of Alcoa<br />

Foundation for their meticulous<br />

way of monitoring this work,<br />

and my fellow colleagues of the<br />

Practitioner Fellowship<br />

programme for their moral<br />

support and well wishes for this<br />

study.

Summary<br />

y research that facilitated through<br />

Alcoa-<strong>IUCN</strong> practitioner fellowship<br />

Mprogramme- 2008 was conducted at<br />

the M S Swaminathan Research<br />

Foundation's Community<br />

Agrobiodiversity Centre in Kerala, India.<br />

By the fellowship research, which took<br />

nearly a year, I have attempted to<br />

establish the link between cultural and<br />

ethnic role of local society in<br />

conservation and sustainable utilization<br />

of five high- value tree species that are<br />

threatened, rare and endemic to the<br />

Western Ghats of India. All the five<br />

species are in <strong>IUCN</strong> threatened<br />

category. The analysis of the data<br />

revealed that the local community men<br />

and women play a key role in<br />

conservation of these species as they<br />

use them in different ways, often<br />

related to their ancient traditions,<br />

customs and belief- system and also in<br />

their livelihood options.<br />

The study brought out all the five<br />

species have spiritual, cultural and<br />

many socio-economic values. It is clear<br />

from the study that such a collective<br />

valuation act as a driver for<br />

conservation of these species. For<br />

instance, the cultural importance of<br />

'white dammar' that extracted from the<br />

species, Vateria indica is attributed to<br />

its utility role in all types of the Hindu<br />

pooja, especially that for the blessings<br />

of God Siva. Many communities in<br />

Kerala use it to fumigate for the<br />

blessings of God and the ancestoral<br />

spirits. The saffron colour sourced from<br />

the seeds of Myristica malabarica is the<br />

characteristic colour of Hindu culture of<br />

whole of India. Likewise, people believe<br />

Marotti oil from Hydnocarpus pentandra<br />

keeps away the evil spirits from home.<br />

It is the most transparent oil, which<br />

creates a spiritual atmosphere<br />

according to local beliefs. The oil has<br />

proven utility in treating leprosy.<br />

A few lessons were learned from this<br />

study. The first lesson I have derived is<br />

that a 'C ' approach can holistically<br />

4<br />

address the issue of conservation. The<br />

study helped me to found that many of<br />

the issues in conservation and<br />

sustainable use of biodiversity can be<br />

achieved through a 'C ' continuum. The<br />

4<br />

C comprises Conservation, which<br />

4<br />

includes enhancement & sustainable<br />

use of biodiversity and comprises in<br />

situ, on farm and ex situ conservation;<br />

Cultivation that promotes low external<br />

input, sustainable farming based on<br />

organic principles; Consumption that<br />

covers sustainable utilization through<br />

conservation and cultivation of life<br />

saving crops, Commerce that create an<br />

economic stake in conservation for<br />

serving simultaneously the causes of<br />

conservation as well as the livelihood<br />

security. The Cultural diversity that<br />

create a spiritual stake in conservation<br />

is an over arching domain. It is<br />

however, noted that there is conflict<br />

exists between linking the dimensions<br />

of commerce and cultural diversity<br />

together. The C approach coupled with<br />

4<br />

a well knitted management plan will be<br />

a highly useful strategy for<br />

revitalization of the cultural traditions,<br />

conservation and sustainable<br />

management of biodiversity.<br />

A second lesson I learned was that<br />

conservation of maximum possible<br />

number of tree species that are<br />

preferred by the communities will help<br />

local communities to address the issue<br />

of climate change. The fellowship<br />

helped me to raise a large number of<br />

seedlings of the selected five species<br />

and contributed to a 50,000 Rare,<br />

Endemic and Threatened plant ('RET')<br />

tree planting campaign of MSSRF by<br />

supplying over 7100 seedlings.<br />

Hundreds of seedlings of these species<br />

are in survivals now in many of the<br />

forest plantations and wild preserved<br />

areas of Wayanad and adjoining<br />

regions.<br />

This fellowship has really increased my<br />

motivation in Human Cultural and<br />

Linguistic Diversity work in species rich<br />

developing countries. Before I accepted<br />

this fellowship, I had very little<br />

knowledge on the co-evolution of -<br />

cultural, spiritual, linguistic and<br />

biological diversities- in the world and<br />

revitalization of the cultural and<br />

lingustic diversity of India. Incidently<br />

my country is with the largest number<br />

of endangered languages of the world.<br />

There is so much has to be done to<br />

save the dying languages and the<br />

dying diversities.<br />

This experience, I am glad to say that<br />

has given me so much enthusiasm and<br />

confidence in working in the area of<br />

conservation. I sincerely thank Alcoa<br />

Foundation and <strong>IUCN</strong> for enabling me<br />

to undertake this short but unique study<br />

and thereby building my conservation<br />

capability. This capability I am sure<br />

would help me to improve my<br />

profession better and better....<br />

N. Anil Kumar<br />

31-10-200

INTRODUCTION<br />

India is one of the 10 top IBCD-RICH countries<br />

of the world. The culture, ethnicity, languages,<br />

biodiversity of India are the oldest and unique, and<br />

with amazing functional attributes. The every- day<br />

life of tribal and rural communities of this country<br />

revolves around these diversities. The South,<br />

North, and Northeast region of India have their<br />

own distinct cultures and almost every state has<br />

carved out its own cultural niche. There is hardly<br />

any culture in the world that is as varied and unique<br />

as India. India is home to some of the most<br />

ancient civilizations, including four major world<br />

religions, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and<br />

Sikhism. Indian religions have deep historical roots<br />

that are recollected by contemporary Indians. The<br />

religious culture going back at least 4500 years has<br />

come down only in the form of religious texts. The<br />

religious beliefs play a dominant part in the history<br />

of Indian religion and these beliefs are at least<br />

10,000 years old.<br />

In a country like India, with its complex<br />

geophysical and cultural characteristics and<br />

traditions, the distributional pattern of religious and<br />

ethnic communities, particularly Scheduled Tribes is<br />

varied. (Hrusikesh etal., 2002) The Indian Society is<br />

not as simple as it looks from the outside. India has<br />

a large tribal population, , totaling of 84.3 million<br />

(8.2%) (Census Report 2001) in 427 tribal<br />

communities (Chandraprakash Kala, 2005). Tribals<br />

01<br />

Sacred grove

are called as Atavika or Adivasi, in general, and are<br />

forest dwellers or forest dependant communities.<br />

The collective knowledge of these communities<br />

about the biodiversity around them is called Ethno<br />

biological knowledge, and it is very ancient in India.<br />

It describes how people of a particular culture and<br />

region make use of indigenous plants and animals.<br />

Ethno biological knowledge that accumulated over<br />

generations help people protect their health and<br />

nutrition and mange their habitats (Laird, 2002).<br />

The possibility that traditional knowledge may be<br />

rapidly and widely lost in response to the growing<br />

economic strength of India has become a major<br />

concern of scholars and policy makers. This<br />

concern emerges from the presumed link between<br />

traditional knowledge, the religious beliefs, cultural<br />

and social attributes of human societies have<br />

substantial influence on biodiversity conservation.<br />

In India, there are biological species closely<br />

interlinked with religious and other ancient<br />

traditions. The recent thrust on biodiversity<br />

conservation and sustainable utilization has<br />

generated interest from the part of conservation<br />

experts and policy makers on the importance of<br />

traditional use of the resources. But, there is no<br />

clear strategic plan exist on how to protect such<br />

knowledge and culture to help conservation of<br />

biodiversity on a long term basis, particularly in<br />

view of rapidly changing culture and life style of<br />

people of India. The traditional uses that are built<br />

up from generations of knowledge and experiences<br />

often proved to be authentic to believe and<br />

followed upon to emulate a strategy for sustainable<br />

conservation methods.<br />

In the Indian wisdom, a tree had been positioned<br />

above all those values that nature bestowed on to<br />

humans. Indian traditional wisdom show practical<br />

and technical uses for tree management in a given<br />

rural landscape and also offers a glimpse of forms<br />

of social and cultural representations concerning<br />

trees. In the ancient Hindu scripture in India, trees<br />

02

are described as an extra terrestrial having its roots<br />

in underworld and branches in heaven. The Hindu<br />

scripture says that the trees unite and connect<br />

beings of all kinds in the world.<br />

In Kerala, there are religiously, socially and<br />

culturally specific tree species once managed in<br />

outside forest landscapes. But many of such wild<br />

tree species have been declined considerably<br />

because of the impacts of modernization. Now<br />

many of them, which are endemic to the forest<br />

environment of Western Ghats are threatened with<br />

the danger of extinction. Trees have played an<br />

important role in Kerala's mythologies and<br />

religions, and have been given deep and sacred<br />

meanings throughout the ages. Keralites, observe<br />

the growth and death of trees, the elasticity of their<br />

branches, the sensitiveness and the annual decay<br />

and revival of their foliage, as powerful symbols of<br />

growth, decay and resurrection. Trees form an<br />

integral part of the culture and heritage of the<br />

people of Kerala.<br />

The present study was for understanding the role<br />

of culture in conserving such tree species, which<br />

are threatened with the fate of extinction. 5 taxa<br />

were selected, viz. Vateria indica Linn, commonly<br />

known as white dammar tree growing in evergreen,<br />

semi-evergreen forests. The resin extracted from<br />

the bark is used as natural incense; Myristica<br />

malabarica Lam. generally known as Malabar Wild<br />

Nutmeg occasionally found in evergreen forests of<br />

Western Ghats, the aril used generally as adulterant<br />

or substitute for nutmeg; Hydnocarpus pentandra<br />

(Buch.-ham.) Oken which is an evergreen tree with<br />

buttressed trunk, commercially known as<br />

Chaulmoogra. The oil extracted from the seeds<br />

have wide application in Indian tradition and<br />

culture; Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd.; a species of<br />

white cedar tree, and Cinnamomum malabatrum (N.<br />

Burm.) Bl, the wild cinnamon.<br />

This report describes the collective efforts of<br />

Alcoa- <strong>IUCN</strong> and MSSRF in conservation of these<br />

species.<br />

03

PROFILE OF<br />

THE STUDY STUDY<br />

SITE<br />

The study location was Wayanad- Nilambur- Silent<br />

Valley region of the Western Ghat part of Kerala<br />

state. It is a region of tribal culture and human<br />

diversity with intensive agricultural land use,<br />

particularly for plantation crops like coffee,<br />

cardamom, pepper, rubber and tea.<br />

04

Wayanad<br />

Wayanad is a picturesque mountainous plateau with<br />

geographical extent of 2131 sq km. The district is<br />

situated at a height ranging from 700 to 2100 m<br />

above mean sea level and lies between north<br />

latitudes 11° 26' 28" and 11° 58' 22" and east<br />

longitudes 75° 46' 38" and 76° 26' 11”. The name<br />

Wayanad, is believed has been derived from the<br />

expression 'Vayal nadu' - the village of paddy fields.<br />

Wayanad, has a total human population of 7,<br />

80,167 comprising about 17% of tribal<br />

communities (Census Report 2001). Wayanad is<br />

considered to be one of the earliest human<br />

settlement areas in Kerala as evidenced by the<br />

historical monuments and other pre-historic<br />

documents.<br />

The district is characterised by cultivation of<br />

perennial plantation crops and spices. The major<br />

plantation crops include coffee, tea, pepper,<br />

cardamom and rubber. Coffee based farming<br />

system is a notable feature of Wayanad. The district<br />

enjoys tropical humid climate with an average<br />

annual precipitation of 3000mm. Wayanad hills are<br />

contiguous to the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu and<br />

Bandhipur in Karnataka, forming a vast land, rich<br />

in biodiversity.<br />

Wayanad is part of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve,<br />

which is one of the biologically rich mega<br />

biodiversity spots of the world. Countless floral<br />

and faunal diversity of greater ecological and<br />

economic importance is getting harboured in the<br />

wild and cultivated landscapes of the district. The<br />

ethnic communities in the district once wholly<br />

depended up on the greens for their health care<br />

system. The onslaught of modernity and the<br />

admixture of population diversity led to the<br />

erosion of ethnic cultural identity and tucked them<br />

away to marginal domain. The tribal communities<br />

of Wayanad district have vast knowledge on those<br />

“uncultivated” but useful plant diversity. Many such<br />

wild biodiversity are in their dietary items. These<br />

include both floral and faunal components and are<br />

generally known as “Ethnic food.”<br />

The district used to be a habitat for wide genetic<br />

diversity of traditional landraces of cultivated food<br />

crops and plantation crops. About 100 rice varieties<br />

were grown in the district suiting to the land<br />

classification and geo-climatic peculiarities. The rice<br />

genetic diversity of the district is known for its<br />

specialty rice varieties having aromatic and<br />

medicinal properties. The rice genetic base of<br />

Wayanad has now narrowed down to around 15-20<br />

rice varieties. One variety of special significance is<br />

Navara rice known for its medicinal value and used<br />

extensively by Ayurvedic practitioners for treating<br />

some aspects of rheumatic complaints. 20 odd<br />

pepper varieties and host of pulse varieties are a<br />

few to highlight. Vegetable and tuber crops occupy<br />

a prominent place in edible crop diversity of the<br />

district.<br />

Wayanad is also known for its medicinal plant<br />

wealth and the indigenous communities who have<br />

profound knowledge on the usage of such plants.<br />

Medicinal plants and other minor forest produces<br />

are now largely traded in local market.<br />

Topographical peculiarities and favorable climate<br />

enrich the potential of mass cultivation of<br />

medicinal and aromatic plants in the district. There<br />

are various species of plants with medicinal uses<br />

cultivated as cash crops or food crops in this area,<br />

Navara being a typical example.<br />

Nilambur<br />

Nilambur in the Malappuram district of Kerala is<br />

famous for its forests, especially its wildlife habitats,<br />

rivers, waterfalls and teak plantations. The name<br />

"Nilambur" means 'Place of Nilimba' (a Sanskrit<br />

word for Bamboo). Nilambur is famous for its<br />

bamboos. It is situated close to the Nilgiris range<br />

of the Western Ghats on the banks of the Chaliyar<br />

River. The town of Nilambur is famous for the<br />

Nilambur Vettekkoru Makan Paattu held every year<br />

in the Nilambur Kovilakom Temple. Nilambur is<br />

also home to the oldest teak plantation in the<br />

world, called Conolly's Plot. It is claimed that the<br />

world's tallest or biggest teak tree is in the<br />

Nilambur Teak Preserve. Cholanaikka are the<br />

dominant tribe in the interior forests of Nilambur<br />

area.<br />

05

Silent Valley<br />

Silent valley is extremely fragile, a unique preserve<br />

of wet evergreen forests lying above the equator<br />

and the forest strip which causes the summer rains<br />

in Kerala. The local name for the park is Sairandhri<br />

vanam (the forest in the valley) which is also one of<br />

the last representatives of tropical evergreen forests<br />

in India. The core of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve<br />

is the Silent Valley National Park. Despite its name,<br />

the Silent Valley (the clamour of Cicadas is<br />

conspicuously absent here) echoes with the sounds<br />

of teeming wildlife. The denizens of this sprawling<br />

habitat of endangered virgin tropical forests<br />

include rare birds, deer and tiger. The park which is<br />

remote has difficult terrain and is surrounded with<br />

Attappadi Reserve Forests in the east, and vested<br />

forests of the Palghat and Nilambur divisions in the<br />

west and south. In the North, the park is an<br />

extension of the Nilgiri Forests. There is no record<br />

the valley has ever been settled, but the Muduga<br />

and Irula tribal people are indigenous to the area<br />

and do live in the adjacent valley of Attappady<br />

Reserved Forest. The Kurumbar community<br />

occupy the highest range outside the park<br />

bordering on the Nilgiris. Many of the Muduga and<br />

Irula now work as day laborers. Some of them<br />

work for the Forest Department in the park as<br />

forest guards and visitor guides.<br />

06

ETHNIC DIVERSITY<br />

Wayanad- Nilambur- Silent Valley Region-<br />

A hotspot for ethnic diversity and culture<br />

The dominant tribal groups of the region are,<br />

Kurichiya, Kuruma, Paniya, Adiya, Kattunaikka,<br />

Cholanaikka and Muduga with other minor<br />

communities namely, Koombaranmar, Kadar, Pulayar,<br />

Mannan, Kuravar, Malayan and Thachanadan Moopan.<br />

The predominant agricultural communities are,<br />

Kurichiya, Kuruma and Wayanadan Chetty. Apart from<br />

tribals Jains, Tamil Brahmins, Hindus, Muslims and<br />

Christian communities are also the inhabitants of<br />

the district.<br />

The tribal communities of the region have vast<br />

knowledge on those “uncultivated” but useful<br />

plants. For example, the Paniya community uses a<br />

large number of plant and small animal diversity,<br />

which includes 72 species of leafy vegetables, 25<br />

species of mushrooms, 19 species of tubers, 48<br />

In Kerala there are 34 different ethnic groups with a total population of 2,61,475 (1.03% only) as<br />

per 2001 Census Report (Hrishikesh et al., 2002) .Cultural exuberances of the tribes of Kerala are<br />

rightly being highlighted in diverse aspects. House building, rituals, norms bore resemblance to the<br />

tradition and ethnicity of the tribal culture. Many of the tribes of Kerala build their settlements in the<br />

forest grounds and the mountains. Due to the rugged topography of the region, the tribes of Kerala<br />

were remained undisturbed by any kind of foreign invasion, which helped them to maintain their<br />

originality intact till in the recent past.<br />

species of fruits and nuts, 36 kinds of native fishes,<br />

8 kinds of crabs and 5 types of wild honey.<br />

The ritualistic ethos of the rural population of the<br />

region is more entwined with agriculture. Each of<br />

the ethnic community has their own culture of<br />

adoration. Putharikayattal a ritual to remark the<br />

harvest of paddy is invariably observed by all<br />

communities in the region. This is to mark the first<br />

rice harvest of the season. Uchal, another festival<br />

observed by tribal communities Kurichiya and<br />

Kuruma, which is related to planting of seeds and a<br />

myth enshrouded with a deity and stored harvested<br />

rice grains where during these periods processing<br />

paddy is forbidden. Rituals also had been in use<br />

(abuse) for instance Kambala Natti- the paddy<br />

transplanting ceremony which is largely promoted<br />

by the landlords to exploit the maximum hard work<br />

of the labour. The workers would be given drinks<br />

and male members of the paniya community will<br />

07

stay on paddy field fringes blowing their traditional<br />

musical instrument (Cheeni) and beating their<br />

musical drums (Thudi). The music and drum<br />

beatings would enthuse them to unleash their<br />

maximum energy and toil from dawn to dusk in the<br />

field. Thulappathu a hunting ceremony observed<br />

by the Kurichya community is an exemplary<br />

instance of current day buzz word sustainable<br />

harvest. Mattalkrishi is custom of agriculture<br />

brought in by the settlers. During the early<br />

migration period they had experienced shortage of<br />

labour to complete the agricultural operation in a<br />

time bound manner. To tide over the crisis of<br />

labour shortage each of the family member come<br />

together to complete the works of each family and<br />

next on subsequent days. This ad hoc mechanism<br />

nurtured collectiveness among farming community.<br />

Such a host of 'rustic' cultures are the entitlements<br />

of the region.<br />

The Communities focused<br />

The study has focused mainly on Kattunaikka,<br />

Paniya Cholanaikkan, Muduga and Kurichya tribes.<br />

Also data collection from other tribes of Wayanad,<br />

Nilambur and Silent Valley has been used to<br />

understand the traditions of conservation of the<br />

selected five tree species.<br />

Kattunaikka<br />

The Kattunaikkan community is one of the most<br />

primitive tribes of South India and found in<br />

Wayanad, Kozhikode and Malappuram districts in<br />

Kerala. They are also called Cholanaikkan, in the<br />

interior forests of Nilambur area and<br />

Pathinaickans, in the plains of Malappuram district.<br />

As their name denote, the Kattunaikkan are the<br />

kings of the jungle engaged in the collection and<br />

Kattunaikka<br />

Kurichiya<br />

gathering of forest produces. They are also known<br />

as Then Kurumar since they collect then (honey)<br />

from the forest and have all the physical features of<br />

a hill tribe. They worship their ancestors, along with<br />

worshipping Hindu deities, animals and birds, trees,<br />

rocky hillocks and snakes. Kattunaikka are firm<br />

believers in black magic and sorcery. They speak a<br />

mixture of all Dravidian languages -the Kattunaikka<br />

dialect, which is but more close to the language,<br />

Kandada. They are non-vegetarian in food habit<br />

and eat a diverse variety of meat. Food gathering,<br />

hunting, fishing and trapping of birds and animals<br />

are the traditional occupation.<br />

Kurichiya<br />

The Kurichiya are an agricultural tribal community<br />

with very rich food habits and hygiene. They are<br />

matrilineal and live in joint families, under the<br />

control of their chieftain called 'Pittan'. The<br />

members of the extended family work together and<br />

put their earnings in the same purse. The Kurichiya<br />

prefer cross-cousin marriage to any other marriage<br />

alliances. They do not practice polyandry. Their<br />

social control mechanism was most efficient,<br />

offenders being excommunicated. Many of the<br />

excommunicated Kurichiya are now educationally<br />

and economically better compared to the traditional<br />

Kurichiya men and women. Recorded history of<br />

Kurichiya tribe is available since the 18th century.<br />

During olden times, this land was ruled by the Rajas<br />

of the Veda tribe. In later days of British<br />

imperialism, the king Kerala Varma Pazhassi Rajah<br />

of Kottayam had to severely contest the<br />

colonialists, tremendously failing in his attempt.<br />

The Kurichiya tribe is equipped with an incredible<br />

martial tradition. In fact, it was this tribe who<br />

represented the army of Pazhassi Rajah, who<br />

battled hostilities with the British forces in a<br />

08

Paniya<br />

number of combats. The descendants of those<br />

warriors are still known to be professional archers.<br />

Paniya<br />

A vast majority of tribal people in Kerala state hail<br />

from the Paniya sect. Paniya inhabit in the regions<br />

of Wayanad and the neighboring parts of Kannur<br />

and Malappuram. As bonded labourers, the Paniya<br />

were once sold along with plantations by the<br />

landlords. They were also employed as professional<br />

coffee thieves by higher castes. The name 'Paniyan'<br />

means 'worker' as they were supposed to have been<br />

the workers of non - tribes. Monogamy appears to<br />

be the general rule among the Paniya. In marriage<br />

bride price is practiced like many other tribal<br />

communities. Widow re-marriage is allowed. They<br />

do not practice pre-puberty marriage. They have<br />

only a crude idea of religion. Their major deity is<br />

called 'Kali'. Paniya also worship Banyan tree and<br />

hesitate to cut such trees as they believe if it is<br />

done so they fall sick.<br />

Cholanaikkan<br />

The Cholanaikkans are one of the most primitive<br />

tribes in South India, numbering only 360 in 1991.<br />

They are called Cholanaikkan because they inhabit<br />

in the interior forests 'chola' or 'shoals' means deep<br />

ever green forest, and 'naikkan' means King. They<br />

are said to be migrated from Mysore forests. They<br />

are one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer tribes<br />

of South India, living in the Silent Valley National<br />

Park (Kerala). They speak the Cholanaikkan<br />

language, but around half of them have a basic<br />

knowledge of Malayalam. The Cholanaikka habitats<br />

are seen in the Karulai and Chunkathara forest<br />

ranges near Nilambur. They were leading a<br />

secluded life with very limited contact to the main<br />

Wayanadan Chetty<br />

stream. The Cholanaikka call themselves as<br />

'Malanaikan' or 'Sholanaikan'. They are generally of<br />

short stature with well built sturdy bodies. The<br />

complexion varies from dark to light brown. The<br />

faces are round or oval with depressed nasal root,<br />

their bridge being medium and the profile straight,<br />

lips are thin to the medium, hair tends to be curly.<br />

They live in rock shelters called 'Kallulai' or in open<br />

campsites made of leaves. They are found in<br />

groups consisting of 2 to 7 primary families. Each<br />

group is called a 'Chemmam'. The Cholanaikans are<br />

very particular in observing the rules framed by<br />

their ancestors for the purpose of maintaining the<br />

territories under the Chemmam. The Chemmams are<br />

found widely scattered in the forest ranges. They<br />

subsist on food gathering, hunting and minor forest<br />

produce collection. Their livelihood is totally<br />

depended on the forest. The collection and selling<br />

of minor forest produce is the major source of<br />

income. There are still many customs, practices and<br />

taboos prevailing among the Cholanaikans.<br />

Wayanadan Chetty<br />

Chetty community of Wayanad district commonly<br />

known by the name Wayanadan chetty is<br />

predominantly a farming community Most of them<br />

are land owners and having better lives than tribal<br />

communities. They follow a harmonious life style<br />

with the local environment share many traditions<br />

and culture that revere nature and natural<br />

agricultural resources comparable to the tribal<br />

communities of the region. The community is<br />

highly religious and believes in nature and animism<br />

worship. Earlier given to nature worship, gradually<br />

they have adopted deities and beliefs of Hindus<br />

who migrated to Wayanad from other districts of<br />

Kerala. (Mathew, 2008)<br />

09

The major objective of the research was to understand the bio-cultural heritage with reference to<br />

the tree (specifically the 5 species selected) human interaction that can be observed within the<br />

dynamic ecosystem in which the communities and these species co-exist. The major<br />

methodologies and tools followed were semi-structured interviews, questionnaire surveys,<br />

personal observations, transect walks and focus group discussions.<br />

METHODOLOGY<br />

The fellow was assisted by two research assistants<br />

in two different occasions and a group of four to<br />

five tribal members in helping him for the<br />

knowledge documentation and collection of seed<br />

materials.<br />

There were a number of locations inhabited with<br />

both Hindu tribal communities (Kurichiya, Muduga,<br />

Paniya, Cholanaikka and Kattunaikka ) and Hindu<br />

non-tribal communities were selected for the<br />

study. These communities are highly rich in<br />

traditional customs. Tribal communities were<br />

experienced in managing natural resources in a<br />

sustainable way as part of their customs. The<br />

central point of the observation was, what role do<br />

the five tree species play in their life? The approach<br />

and methodology adopted for the study are as<br />

follows.<br />

Literature Survey<br />

As an initial step of research, taxonomic account<br />

of all the 5 species collected. In order to<br />

understand the distribution of the species, visits<br />

were made to herbaria like Calicut University<br />

Herbarium (CALI), Kerala Forest Research<br />

10

Institute (KFRI), and Botanical Survey of India<br />

Herbarium, Coimbatore (MH).<br />

Secondary data collection was carried out from the<br />

various organizations in Kerala state like<br />

Directorate of Scheduled tribes development,<br />

Tribal extension offices in Palakkad, Malappuram<br />

and Wayanad, Kerala Forest Department, District<br />

Panchayath, NGOs working in tribal area. The<br />

preliminary information was supplemented with<br />

the maximum available secondary data gathered<br />

through literature survey (Faulks, 1958; Ford, 1978;<br />

Jain 1981; Varghese, 1996; WWF, 1997; Jain, 2004;<br />

Maffi, 2004; Sasidharan, 2004; Anil Kumar et al.,<br />

2009)<br />

Field Work<br />

This work is the result of personal observations<br />

and interviews made after carefully planned field<br />

work during April 2008- May 2009. 21 Colonies of<br />

Kattunaikka, 4 colonies of Kurichya in Wayanad<br />

district, 12 colonies of Muduga in Silent Valley and<br />

8 colonies of Cholonaikka in Nilambur visited and<br />

semi-structured interviews were carried out using<br />

questionnaire (Annexure 1). An album having<br />

detailed, and good quality photographs of the 5<br />

trees were also used to show for their easier<br />

identification.<br />

Informants were included men, women, children,<br />

youth, middle-aged and old people among tribes<br />

(Annexure 2). 10 key informants were selected<br />

from the first category and detailed information<br />

regarding the five tree species pertain to uses such<br />

as domestic, medicinal, commercial and religious<br />

practices were collected. The non-tribal Hindus like<br />

Nair, Thiyya, Brahmin, Wayanadan Chetty were also<br />

interviewed. (Annexure 3). Many Kaavu (Sacred<br />

groves) and temples in various locations of Kerala<br />

were visited for the data collection.<br />

Flowering and non-flowering twigs of the 5 species<br />

were collected with maximum variables from each<br />

location. Seed materials (that are usually vulnerable<br />

to get washed off in the rain) of these species were<br />

gathered from the trees that found near forest<br />

fringes to raise nursery at station and country level.<br />

Seeds were germinated in the nursery conditions at<br />

CAbC, MSSRF which showed all the species have<br />

above 50% germination rate. (See the table and<br />

figure below)<br />

Fig. 1<br />

Percentage of seed germination of the targeted species<br />

100<br />

0<br />

87.15<br />

69.09<br />

50.87<br />

84.89 86.32<br />

No. Name of the species Number of Number of<br />

Seeds tried seedlings raised<br />

1 Vateria indica Linn. 1586 1369<br />

2 Myristica malabarica Lam. 1410 1197<br />

3 Hydnocarpus pentandra (Buch.-ham.) Oken 2300 1589<br />

4 Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. ex Hiern 2467 1255<br />

5 Cinnamomum malabatrum (N. Burm.) Bl. 2000 1743<br />

11

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF<br />

THE SPECIES STUDIED<br />

Proctectd tree of vateria indica in front of a temple<br />

12

Cinnamomum malabatrum (N. Burm.) Bl.<br />

Wild Cinnamon<br />

Botanical Name : Cinnamomum malabatrum (N. Burm.) Bl.<br />

Family : Lauraceae<br />

Synonyms : Laurus malabatrum Burm. f., Cinnamomum iners sensu Gamble<br />

Malayalam Name : Karuppa, Vayana<br />

Hindi Name : Jangli darchini<br />

Tamil Name : Kattukaruvappattai<br />

Kannada Name : Adavi lavangapatte<br />

Large trees, grow up to 20 m height. Bark smooth<br />

or slightly longitudinally cracked, brown in colour<br />

and aromatic. Leaves are opposite or sub-opposite,<br />

oblong, elliptic or sub-obovate- elliptic. Flowers are<br />

small, bisexual, many, pale or greenish white in lax<br />

terminal panicles. Fruits berry.<br />

Cinnamon - botanically known as Cinnamomum<br />

verum is a native species of Sri Lanka and is<br />

endemic to that region. This species has been<br />

introduced long back to India in the wet areas of<br />

southern region and successfully established there<br />

in the homesteads. The southern region of India,<br />

especially Western Ghats holds several species of<br />

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF THE SPECIES SPECIES STUDIED<br />

STUDIED<br />

Cinnamomum in wild and some of them are in close<br />

resemblance with that of Cinnamomum verum or the<br />

true Cinnamon. The common example is<br />

Cinnamomum malabatrum or wild cinnamon. The wild<br />

cinnamons of this region are widely used to<br />

adulterate the cultivated cinnamon and also as an<br />

important raw material for the Agarbathy industry.<br />

Karuppa or Cinnamomum malabatrum is a widely<br />

exploited wild species for the purpose of its<br />

commercially valuable bark. This species endemic<br />

to the Western Ghats and is now in a critically<br />

dangerous condition. The species Cinnamomum<br />

malabatrum is exclusively endemic to the southern<br />

13

Western Ghats and is more confined to the Nilgiris,<br />

Silent Valley-Kodagu area (Nayar M.P., 1996). The<br />

Nilgiris -Silent Valley, Kodagu area covers 12800 sq.<br />

km hold about 150 endemic species. Some other<br />

endemic species of Cinnamomum occurring in this<br />

area are: Cinnamomum walaiwarnese, C. heyneanum, C.<br />

filipedicellatum, C. keralense, C. macrocarpum, C.<br />

riparium, C. travancoricum and C. wightii.<br />

Cultural, Medicinal and Economic Value<br />

The aromatic leaves are used to make a special kind<br />

of leafy bowl for preparing a traditional food item<br />

'Therali” for the blessing of the Goddess<br />

“Bhadrakali”. Another delicious food “Ada” is also<br />

prepared in the leaves of this species. Fumigation<br />

of flower is an important ritual in tribal customs.<br />

Number of individuals using Cinnamomum<br />

malabathrum for various purposes<br />

8<br />

2<br />

Tribes using Cinnamomum malabatrum<br />

for various purpose (in %)<br />

1<br />

4<br />

Number of individuals using Cinnamomum<br />

malabathrum for various purposes<br />

8<br />

2<br />

1<br />

4<br />

20<br />

20<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

Comercial uses<br />

Religious practices<br />

Not used<br />

The plant is used by the Kani Tribe in<br />

Agasthyamala region for alleviating stomach pain,<br />

digestion problems as well as for treating wounds,<br />

fever, intestinal worms, headaches and menstrual<br />

problems. The aromatic bark of the tree is much<br />

extracted for medicinal purposes. The bark is<br />

known to be astringent, laxative, stimulant, and<br />

carminative, antispasmodic. Bark is used as a<br />

flavouring agent in medicine (Krishnamurthy,<br />

1993). Bark is also used as condiment. Oil from<br />

leaves called “clove oil” is used against teeth ache,<br />

headache and rheumatism. Muduga people used the<br />

leaves for teeth cleaning.<br />

The highly aromatic bark and leaves of the species<br />

are widely exploited for the commercial extraction<br />

of volatile oils used in perfumery industry. The<br />

bark is also used to make inscent sticks. The<br />

immature fruits are used as a raw material in paint<br />

industries. Bark is used for the preparation of<br />

match boxes (Nair and Nair, 1985). Flower is used<br />

for fumigation.<br />

Conservation efforts<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Cinnamomum malabatrum flowers during December -<br />

March Medicinal and mature uses fruits are during June- August.<br />

The seeds are dispersed mainly by birds away to<br />

distance Comercial where they uses germinate in rainy season. For<br />

artificial regeneration of C. malabatrum, ripen fruits<br />

collected Religious and they practices are to be soaked in water for 12-<br />

24 hrs Not before used sowing. In the nursery, seeds are<br />

either broadcast sown or dibbled in manured beds<br />

watered regularly. The seedlings can be pricked out<br />

in to polythene bags when they are six months old.<br />

The percentage of germination of C. malabatrum as<br />

per above method was 87.15 % (Fig.1). 1743<br />

seedlings were raised and distributed.<br />

14

Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. ex Hiern<br />

White Cedar<br />

Botanical Name : Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. ex Hiern<br />

Family : Meliaceae<br />

English Name : White cedar<br />

Malayalam Name : Vella akil<br />

Tamil Name : Vellayagil<br />

Kannada Name : Bilibudlige<br />

Large trees up to 40 m height, rough greyish-yellow<br />

bark and inner bark creamy yellow. Leaves alternate<br />

or sub opposite, abruptly pinnate with angular<br />

rachis. Leaflets alternate, opposite or sub opposite,<br />

elliptic-oblong, entire, puberulous when young,<br />

rounded at base, acuminate at apex. Flowers are<br />

bisexual, greenish yellow. Fruits are capsule. Seeds<br />

stored at wet bags for artificial regeneration (FRI,<br />

1981).<br />

Cultural, Medicinal and Economic Value<br />

Vellakil is a constituent of “ashtagandha”, which<br />

produce a fragrant smell. Wood is used for the<br />

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF THE SPECIES STUDIED<br />

production of inscent sticks. It is also used in the<br />

absence of sandal. But there is no Sandal wood tree<br />

in a forest in which there is Vellakil (Nair and Nair,<br />

1985). Vellakil is used to fumigate the “Yaga”- an<br />

offering to God and “Homa” centers. Fumigation<br />

of Dysoxylum malabaricum is very important in the<br />

'Oorukoottam” or Kurichiya country. This tree is<br />

mainly seen on dense forests and sacred groves. In<br />

ancient times no one was ready to exploit the<br />

sacred groves as part of the custom, because of<br />

that these trees are still protected.<br />

Decoction of wood is useful in arthritis, anorexia,<br />

cardiac debility, expelling intestinal worms,<br />

15

inflammation, leprosy & rheumatism (Kumar,<br />

2005). Wood oil is used in treating ear and eye<br />

disease (Jain an d Dafilips, 1991). In Sidha, the plant<br />

is known as Agil and is used as a substitute for<br />

Aquilaria malaccensis (Kumar, 2005).<br />

Number of individuals using Dysoxylum<br />

malabaricum for various purposes<br />

Number of individuals using Dysoxylum<br />

20%<br />

malabaricum for various purposes<br />

16<br />

53.34<br />

16<br />

Tribes using Dysoxylum malabaricum<br />

for various purpose (in %)<br />

3<br />

4<br />

6<br />

1<br />

3<br />

10%<br />

4<br />

13.33<br />

6<br />

1<br />

0.03%<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Medicinal us es<br />

Comercial us es<br />

Religious practices<br />

Not us ed<br />

The timber of white cedar tree is highly reputed.<br />

The wood is an important constituent in the<br />

perfumery and ply wood industry. The wood is also<br />

used for making motor truck bodies, furniture,<br />

carts, railway carriages toys and textile wooden<br />

accessories like bobbins (Gopimani1991) (Jain, S.K,<br />

Dafilips A Robert 1991). It is also good for<br />

cooperage especially tight cooperages and for the<br />

frame work of carts and carriages.<br />

Conservation efforts<br />

Dysoxylum<br />

Domestic<br />

malabaricum<br />

purposes<br />

flowers during February<br />

April and mature fruits ripens during June July.<br />

The Medicinal tree regenerates uses naturally from the seeds<br />

contained<br />

Comercial<br />

in<br />

us<br />

the<br />

es<br />

fallen fruits, unless removed or<br />

destroyed by wild animals, which is quite prevalent<br />

(Nair, Religious 2000). practices Seeds of D. malabaricum were<br />

collected<br />

Not us ed<br />

during June-July from ripened fruits and<br />

sown in nursery beds made of sand and soil in the<br />

ratio of 3:1 and it was noted within 70 days,<br />

germination was completed. The seedlings, which<br />

attained 30-35 cm, by the next rainy season were<br />

field planted. The percentage of germination of C.<br />

malabatrum as per above method was 50.87 % (Fig.<br />

1). 1255 seedlings were raised and distributed.<br />

16

Hydnocarpus pentandra (Buch.-ham.) Oken<br />

Chaulmoogra<br />

Botanical Name : Hydnocarpus pentandra (Buch.-ham.) Oken<br />

Family : Flacourtiaceae<br />

English Name : Chaulmoogra<br />

Malayalam Name : Marotti<br />

Tamil Name : Maravetti<br />

Kannada Name : Toratti<br />

Medium sized trees with buttressed trunk up to<br />

15m height. Leaves are simple, alternate, ovate,<br />

elliptic or lanceolate, entire or obscurely serrate,<br />

glabrous. Flowers greenish yellow in solitary or few<br />

flowered, axillary cymes or fascicles. Fruits berry.<br />

Cultural, Medicinal and Economic Value<br />

Marotti is seen in most of the sacred groves of<br />

Kerala. There are believes that presence of Marotti<br />

is the sign of water in the land. Still the tribal<br />

communities in Wayanad consider the presence of<br />

this species as an indicator of water. Seed oil is<br />

used for lightening the lamps in many tribal<br />

communities; they believe that light from Marotti oil<br />

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF THE SPECIES SPECIES STUDIED<br />

STUDIED<br />

will keep away the evil spirits. Marotti oil is the most<br />

transparent oil, which creates a spiritual<br />

atmosphere. Seed coat is used as lamps in their<br />

worships which is long lasting and have a holistic<br />

smell. Kattunaikka use the mature seed for capturing<br />

fishes in the traditional way.<br />

Seed, oil, young leaves and root are used for<br />

medicinal purpose. The seed oil is used for relieving<br />

pains, heals scabby body, leprosy, rheumatism,<br />

chronic skin affections, sprains, ophthalmia, and<br />

removes itching from the affected parts when<br />

smeared with it. Oil mixed with ashes is used treat<br />

wounds on cattle's. According to Ayurveda<br />

consumption of purified seeds will increase the life<br />

17

time of human beings, but the impure plant parts<br />

are toxic. The knowledge on traditional use of seed<br />

oil aganist leprosy is common.<br />

Number of individuals using Hydnocarpus<br />

pentandra for various purposes<br />

13<br />

19<br />

49<br />

23<br />

Number<br />

10.08%<br />

of individuals using Hydnocarpus<br />

pentandra for various purposes<br />

13<br />

19<br />

49<br />

Tribes using Hydnocarpus pentandra<br />

for various purpose (in %)<br />

14.73%<br />

37.98%<br />

23<br />

25<br />

17.83%<br />

25<br />

19.38%<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

Comercial uses<br />

Religious practices<br />

Not used<br />

The kernels weigh 70% of the seed weight yield<br />

63.25% of oil (Krishnamurthy, 1993). The oil used<br />

as an illuminant. Fruits are used as a fish poison by<br />

Muduga and Kattunaikka. Wood is perishable; timber<br />

is only used for furniture purpose. Seed oil is used<br />

for manufacturing soaps.<br />

Conservation efforts<br />

Hydnocaropus pentandra flowers during February-<br />

March Domestic or in July- August purposes and fruits during October-<br />

December mature by March April. The tree is a<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

mostly a riverine species. Fresh seeds were collected<br />

during Comercial March- April, uses sun- dried and sown in the<br />

nursery bed equal part of soil, sand and compost<br />

(1: 1:1). Religious The percentage practices of germination of H.<br />

pentandra<br />

Not<br />

as<br />

used<br />

per above method was 69.09 % (Fig1).<br />

1589 seedlings were raised and distributed.<br />

18

Myristica malabarica Lam.<br />

Wild Nutmeg<br />

Botanical name : Myristica malabarica Lam.<br />

Family : Myristicaceae<br />

Malayalam Name : Kattujathikka, pasupasi, ponnampayin, Patri<br />

English name : Bombay nutmeg<br />

Hindi Name : Van-jayphal<br />

Tamil Name : Pattiri<br />

Telugu Name : Vani<br />

A medium sized tree, grows up to 25m height. Bark<br />

greenish white, red inside with a red exudation.<br />

Branchlets are glabrous. Leaves are simple,<br />

alternate, oblong or elliptic lanceolate, glabrous<br />

above, glacous beneath. Flowers are unisexual,<br />

yellow, axillary in pedunculate, dichasial cymes.<br />

Female flowers are slightly larger than male,<br />

peduncle generally simple with 3 umbelled pedicels<br />

at the apex. Fruit a capsule, oblong, pubescent with<br />

one oblong and obtuse seed. Aril is yellow,<br />

irregularly lobed, extending to the apex of the seed.<br />

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF THE SPECIES SPECIES STUDIED<br />

Cultural, Medicinal and Economic Value<br />

In ancient times saffron colour is extracted from<br />

the seeds of Myristica malabarica. Saffron is one of<br />

the characteristic colour of the Hindu culture. Seed<br />

coat is used as food. Seed and aril are used as<br />

medicine. Aril is used as medicine for stomach pain.<br />

Fat from the seed is used as an embrocation in<br />

rheumatism, myalgia, vata, sprains, sores and pain.<br />

The aril of the seed is cooling, febrifuge and<br />

expectorant and is useful in vitiated conditions of<br />

cough, fever, bronchitis and burning sensations. Fat<br />

19

is mixed with little oil and applied to persistent<br />

ulcers.<br />

Number of individuals using Myristica malabarica<br />

for various purposes<br />

0% 0<br />

11<br />

er of individuals using Myristica malabarica<br />

for various purposes<br />

0<br />

11<br />

19<br />

26.19%<br />

3<br />

Tribes using Myristica malabarica<br />

for various purpose (in %)<br />

9<br />

19<br />

45.24%<br />

3<br />

7.14%<br />

9<br />

21.43%<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

Comercial us es<br />

Religious practices<br />

Not us ed<br />

The aril is commonly called as ponnampu (golden<br />

flowers) and the tree “ponnampayin”. Ponnampu has<br />

its own economic value as a raw drug, but it is more<br />

remunerative for the merchants when it is used as<br />

an adulterant for the Myristica fragrans- the<br />

commercial Nutmeg. The bark of the tree yields<br />

gum also. Seed kernels contain a resin, which is<br />

phenolic in nature and can be used an antioxidant<br />

for the protection oils and fats against rancidity. Fat<br />

is used as an illuminant by Kurichiya. Muduga<br />

community Domestic use the seed purposes oil as fuel. Wood is used in<br />

building constructions, tea boxes, match boxes,<br />

splints and Medicinal for light furniture. uses<br />

Comercial us es<br />

Conservation efforts<br />

Religious practices<br />

Myristica malabarica flowers mostly during February<br />

March and Not fruits us ed ripen by December - January. In<br />

natural conditions, the seeds dispersed germinate<br />

during rains. In the nursery, seeds were sown in the<br />

bed of sand and farm soil (3:1) and watered<br />

regularly. The percentage of germination of M.<br />

malabarica was 84.89% (Fig 1).There are about 1197<br />

seedlings raised and distributed of this species.<br />

20

Vateria indica Linn.<br />

White Dammar Tree<br />

Botanical Name : Vateria indica Linn.<br />

Family : Dipterocarpaceae<br />

Malayalam Name : Vellappayin, telli, Vella kundirikkam<br />

English Name : Indian Copal tree<br />

Hindi Name : saphed dammar<br />

Tamil Name : Painimaram<br />

Telugu name : Dupadamaru<br />

Large trees, reaching up to 40 m height. Trunk is<br />

smooth, grayish white bark. Branchlets are hoary<br />

stellate-pubescent. Leaves are simple, oblong or<br />

elliptic-oblong, glabrous. Flowers are bisexual,<br />

white, fragrant in long terminal or lateral<br />

corymbose panicles. Fruits are pale brown capsule.<br />

Cultural, Medicinal and Economic Value<br />

Vellappayin is the source of “vella kundirikkam”<br />

(white Dammar) which is an oleo-resin extracted by<br />

wounding the bark towards the beginning of dry<br />

season. Vella kundirikkam have high importance in<br />

BIO-CULTURAL VALUE OF THE SPECIES SPECIES STUDIED<br />

STUDIED<br />

customs of all the communities studied as well as<br />

others.<br />

Burning of white Dammar purifies the<br />

surroundings and this is an essential part of all type<br />

of the Hindu poojas especially for the blessings of<br />

God Siva. Muduga of Silent Valley use to fumigate<br />

White Dammar for the blessings of their God.<br />

Kattunaikka used this as “vella pantham” before the<br />

Goddess “Kali” and also in the rituals connected<br />

with Sabarimala pilgrims. On the time of traditional<br />

customs, they fumigate Vella pantham with honey.<br />

White Dammar is considered as the representative<br />

21

tree for the star “moolam”. Hindu communities<br />

believed that the persons whom born in Moolam<br />

star must worship the tree for their progress. Dried<br />

seed of Vateria indica is used to fumigate with<br />

turmeric in spiritual events. Furit shell is used for<br />

the purpose as lamps by Kattunaikka and the<br />

dammar for warding off evil spirits.<br />

Resin is reported to be a tonic, depurative,<br />

carminative, expectorant and an effective pain<br />

reliever. It is used widely for fumigation and to heal<br />

chronic wounds. Also it is used to cure throat<br />

troubles, chronic bronchitis, urethrorrhea, anaemia,<br />

haemorrhoids, hemicrania, piles, diarrhoea,<br />

rheumatism, tubercular glands, gonorrhea and<br />

ulcers. The resin is applied as an effective remedy<br />

for joint pain, arthritis and headache. Resin acts<br />

against dysentery and obesity. It has got a bitter<br />

Number of individuals using Vateria indica for<br />

various purposes<br />

17<br />

18.89%<br />

Tribes using Vateria indica<br />

for various purpose (in %)<br />

6<br />

20<br />

Number of individuals using Vateria indica for<br />

various purposes<br />

17<br />

44<br />

48.89%<br />

44<br />

6<br />

6.67%<br />

20<br />

3<br />

22.22%<br />

3<br />

3.33%<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

Comercial uses<br />

Religious practices<br />

Not used<br />

taste, seethe veerya (cold dominated therapeutic<br />

action), and snigdha properties (able to provide<br />

soothing effect). Fumigation is recommended for<br />

fever, jaundice, and for viral infections. Seed oil is<br />

used against rheumatism and neuralgia. Bark is an<br />

alexipharmic, used in Ayurvedic preparations. Fruit<br />

shell is also used for tanning. In Kalarippayattu- the<br />

traditional martial arts of Kerala, the resin is used<br />

in a preparation of 'Marmagulika' which is used for<br />

the treatment of muscles fractures of and in<br />

preparation of body massage oil.<br />

Timber is normally not strong, but it is said by<br />

chemical treatment quality can be increased. Tribal<br />

people used the timber for the preparation of<br />

houses. Timber is commonly used by plywood<br />

industry (Kumar, 2005) Timber is used for the<br />

preparation of tea chests, coffins, floorings,<br />

ammunition boxes and oars for sea going vessels.<br />

Resin fumigation is effective against insects and<br />

mosquitoes. The oleoresin mixed with coconut oil<br />

makes an excellent varnish (Nair and Nair 1985).<br />

Dried resin is used for the preparation of inscent<br />

sticks and for paint industry. Seed oil is used for<br />

the preparation of soap (Gopimani 1991).<br />

Domestic purposes<br />

Conservation efforts<br />

Medicinal uses<br />

Vateria indica flowers mostly during February- April<br />

and fruits Comercial mature by July- uses August. The matured<br />

fruits are fallen and regenerated naturally. The<br />

Religious practices<br />

ripened and dispersed fruits containing seeds were<br />

gathered Not during used June- July. Seeds were sown in<br />

polythene bags filled with sand and farm soil (3:1).<br />

The seedlings can be maintained in the nursery till<br />

the next planting season. The percentage of<br />

germination of V. indica as per above method was<br />

86.32 % (Fig 1). There are about 1369 seedlings of<br />

this species raised and distributed.<br />

21

BENEFITS FROM<br />

THE STUDY<br />

This Report has outlined results of an action<br />

research that undertaken for a period of one year<br />

with help of the indigenous and traditional people<br />

of Wayanad-Nilambur-Silent Valley region of<br />

Western Ghats, India. The major objective of this<br />

short- term research was to develop a more<br />

effective approach in conservation of a group of<br />

five plant species that to represent the entire rare,<br />

endemic and threatened tree taxa of the region.<br />

The study had attempted to prove the importance<br />

of ethnic group diversity, cultural diversity, religion<br />

diversity and plant diversity as an effective<br />

mechanism for conservation and adaptation<br />

options of the local communities to manage the<br />

bio-resources in their surroundings. The present<br />

study had also attempted to explore the links<br />

between economic, social and cultural factors<br />

contributing to the sustainable use of plant by<br />

examining the case of the five tree taxa selected.<br />

Three questions were asked in this study viz., (i)<br />

what are the factors and lessons to be learnt from<br />

the local communities in the management of native<br />

tree species, particularly those are rare and/ or<br />

threatened? (ii) what are the best approaches and<br />

strategies that ensure optimum use of the tree<br />

diversity for addressing the issue of climate change?<br />

(iii) what are the research gaps in the subject area<br />

of biodiversity in relation with the fabulous IBCD<br />

Richness of the region?<br />

It is observed that the culture- a trigger for<br />

protection of biodiversity do not operate in<br />

isolation, but in combination with four other<br />

factors and contribute to sustainable management<br />

of bio resources at community level. These are:<br />

conservation of socio-economically and<br />

ecologically valuable species, cultivation through<br />

production and distribution of planting materials<br />

of economically important species at community<br />

level, consumption through creation of awareness<br />

22

and education about the native valuable species and<br />

commercialization at local level to deal with<br />

market involvement of the native species. But, all<br />

these four factors need not work together<br />

simultaneously, rather domination of materialistic<br />

and commercial values and practices, which often<br />

unsustainable in operation in society. This C4<br />

continuum, if done consciously well, by keeping<br />

the protection of IBCD richness in mind, it can<br />

turn out to be an effective approach and strategy<br />

for biodiversity conservation, more so that in<br />

outside protected areas. In rural and tribal areas of<br />

a country like India where multi-lingual, multiethnic<br />

culture dominates, even without any legal or<br />

regulatory mechanism, there is much scope for this<br />

C4 approach as a strategy to “protect and<br />

encourage customary use of biological resources in<br />

accordance with traditional cultural practices that<br />

are compatible with conservation or sustainable use<br />

of requirements”- the article 10 (c) of CBD. The<br />

study benefitted in strengthening this C4<br />

continuum as described below.<br />

1.Strengthening Conservation<br />

The 2006 <strong>IUCN</strong> Red List of Threatened Species<br />

that includes 350 vascular plant species from India<br />

carries many endangered species in which 203 are<br />

found in the Western Ghats. The once wide spread<br />

'trees of outside forests' in the moist hilly regions<br />

of many parts of Western Ghats are getting<br />

vanished because of logging for wood, agricultural<br />

development, pioneer settlements, drought, and<br />

forest fires. Most of these species could be<br />

multiplied and raised as agro-forestry.<br />

Conservation succeeds only when people<br />

understand the value of it and cooperate in such<br />

efforts whole-heartedly. The present study<br />

attempted to raise awareness of the public and the<br />

leaders of religious institutions like temple, church<br />

and mosque about the 'cultural and biological<br />

richness' of the region and importance of<br />

conservation of such richness and diversity. There<br />

were 7153 seedlings raised in the five species and<br />

contributed to a '50,000 RET Tree Planting<br />

Campaign' under an initiative of M. S.<br />

Swaminathan Research Foundation’s Saving<br />

Endangered Species. Such a Tree planting campaign<br />

that aimed at enhancing the tree diversity in<br />

protected forests and outside forest areas in shade<br />

grown coffee plantations will be a most efficient<br />

and economical way to curb atmospheric carbon to<br />

a greater extend. There is however, the allocation<br />

of resources for research and development of<br />

knowledge and sciences of local communities<br />

about conservation is very inadequate today in this<br />

part of the country. Support to cultural and<br />

community based institutions is required to help<br />

effective practices in community conservation and<br />

23

ural development and in turn to lead more<br />

enlightened public policy.<br />

2.Promoting Cultivation<br />

The Rio Declaration on Environment and<br />

Development calls for all States and all people to<br />

cooperate in the essential task of eradicating<br />

poverty as an indispensable requirement for<br />

sustainable development, in order to decrease the<br />

disparities in standards of living and better meet<br />

the needs of the majority of the people of the<br />

world. Cultivation of culturally, spiritually and<br />

economically important species, if it is promoted in<br />

a sustainable way will be an important step for<br />

income generation and can function as a strong<br />

pillar that promotes conservation at a larger scale.<br />

All the five tree species are not only of RET, but<br />

of major economic importance as the source of<br />

products such as timber, fruits, nuts, resins and<br />

gums for many of the local and forest dwelling<br />

communities. The seedlings raised were distributed<br />

with an objective of promoting agro-forestry in<br />

both public and private lands looking into<br />

conservation of native tree species. Also mooted<br />

plans to establish community seed banks of those<br />

seed bearing RET trees of the region and manage<br />

such banks in line with the joint forest management<br />

mechanism<br />

3.Promoting Consumption<br />

Education is required to promote sustainable<br />

consumption and to influence the local spirituality,<br />

religions and belief systems. Records show, out of<br />

the 319 endemic trees found in Kerala, 133 have<br />

got local names that denote either its specific<br />

usefulness or characteristics helping the species<br />

employed in a diverse manner by the local<br />

communities. MSSRF is involved widely in<br />

educating the decision makers on the need of<br />

sustainable management of resources and where<br />

the need of recognizing the role of local<br />

Nursery of RET plants at CAbC MSSRF<br />

24

communities in revitalization of the conservation<br />

traditions. There was a suggestion from Shri. Jairam<br />

Ramesh, the Hon'ble Minister for Environment<br />

and Forests, Govt of India while he was at<br />

MSSRF-CAbC to set up Vana Vigyan Kendra<br />

(Forest Resource Centre) for the purpose of<br />

grooming the forest dwelling communities to<br />

access sustainable livelihoods in various forest<br />

related occupations, and enhance their knowledge<br />

and skills in conservation, sustainability and<br />

stewardship of forests. This can be achieved by<br />

educating and training the local community men<br />

and women in the fundamental concepts,<br />

knowledge, and skills of forest and biodiversity<br />

sciences. The experience from the study helped to<br />

develop a proposal on this concept, which be<br />

supported by the Ministry of MoEF. The project is<br />

intended to start four such Vana Vigyan Kedras- 2<br />

in Western Ghats and 2 in Eastern Ghats.<br />

4.Promoting Responsible Commerce<br />

This is essentially for building local economies and<br />

for retaining benefits in the local area. An<br />

opportunity in this regard is the trading option of<br />

people in carbon credits because of the nonbinding<br />

commitment of India to the Kyoto<br />

protocol. Carbon credits of RET trees will be a<br />

very significant commercial venture in creating an<br />

economic stake in conservation. The sale of<br />

carbon credits that largely leveraged on RET Trees<br />

will be unique in the world where both<br />

conservation of endangered species and<br />

sequestering of carbon would achieve by a single<br />

attempt. This attempt can help India to increase the<br />

greenery of the country and volume of spot sales<br />

in carbon trading as well as accrue the profit to<br />

domestic project owners. Besides, there is a plan to<br />

attempt on marketing plantation nurseries<br />

of those high timber value RET trees by<br />

organizing supply of quality planting<br />

materials. The income generation<br />

process by commercializing<br />

products such as tree saplings and ecosystem<br />

services without undermining the cultural values<br />

can prove a major improvement option in the lives<br />

of poorest in the intervention site of this project. It<br />

is possible to mobilize the local communities to go<br />

for larger scale planting of the RET trees of the<br />

region.<br />

5.Revitalisation of Cultural traditions<br />

This research was intended to build an example of<br />

concrete action to help people to keep alive the<br />

local traditions of biodiversity conservation and<br />

sustainable utilization. It may also contribute in the<br />

discussions related to endogenous development.<br />

Though the gender perspective on bio-cultural<br />

diversity in different cultures is important, it had<br />

not been attempted in the survey. The<br />

communities, I have worked are those who have<br />

vital traditions, and diversity in culture, ethnicity<br />

25

and language, but simultaneously most of them<br />

experiencing rapid cultural changes and<br />

degradation of their ecosystems. The conservation<br />

tradition, though it was deeply embedded in the<br />

local culture and lifestyle in the past, people now<br />

experience changes, for example in languages,<br />

beliefs, values, rituals and the daily practices. Once<br />

the culture -based knowledge is being subjected to<br />

erosion, it impacts several other domains such as<br />

mainly resource management and utilization<br />

behaviour. I found that the once wide spread 'trees<br />

of outside forests' in the moist hilly regions of<br />

many parts of the study areas are getting vanished<br />

because of logging for wood, agricultural<br />

development, pioneer settlements, drought, and<br />

forest fires. It is understood that this is because of<br />

the limited information on the distribution and<br />

conservation status of the threatened tree species<br />

of outside forest areas. Community and location<br />

specific campaign for revitalization of cultural<br />

ethos and habits is needed to promote conservation<br />

of the RET species. Several steps are in mind to<br />

curve this situation. (See the portion conclusions<br />

and steps ahed)<br />

26

CONCLUSIONS & THE STEPS<br />

AHEAD<br />

My experiences and knowledge have been rich<br />

from the study. A major lesson I have learned was<br />

that the interdependence of cultural, linguistic and<br />

biological diversity at local scale is vital, but<br />

unfortunately no concerted efforts aiming this<br />

strategy as a conservation approach emerge either<br />

from the state, the country or local institutions.<br />

This is mainly due to the lack of the “do how”<br />

knowledge to effectively integrate cultural<br />

dimensions with the mainstream conservation or<br />

sustainable developmental plan. This is the high<br />

time to take more effective actions to promote high<br />

quality tree conservation research and protection of<br />

society from the danger of climate change or<br />

species extinction. In order to continue this kind of<br />

research and action, enough research fellowships<br />

have to be promoted in the major impact areas like<br />

conservation and Bio-cultural diversity. The study<br />

results, have the potential to contribute the national<br />

biodiversity strategy and action plan and achieving<br />

the 2010 -biodiversity targets, specifically to the<br />

issues related to Article 8(j) and related provisions<br />

Along with Dr Julia Marton- Lef’vre, Director General of <strong>IUCN</strong> (third from left) and Dr Jeffrey<br />

Mc.Neely, Chief Scientist of <strong>IUCN</strong> (second from right) and the other Alcoa-<strong>IUCN</strong> 2008<br />

Practitioner Fellows<br />

27

of CBD. The learning also help to contribute<br />

towards effective implementation of some of the<br />

provisions of Indian Biodiversity Act 2002.<br />

In my capacity as the Director of Biodiversity<br />

Programme of MSSRF, I have plans to address the<br />

issue of cultural erosion through dissemination of<br />

the findings of this study as a reliable indicator data<br />

on the positive aspects for developing a suitable<br />

management plan for conservation of 'RET' plant<br />