Did St. Thomas Aquinas Justify the Transition from 'Is' to 'Ought'

Did St. Thomas Aquinas Justify the Transition from 'Is' to 'Ought'

Did St. Thomas Aquinas Justify the Transition from 'Is' to 'Ought'

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

39<br />

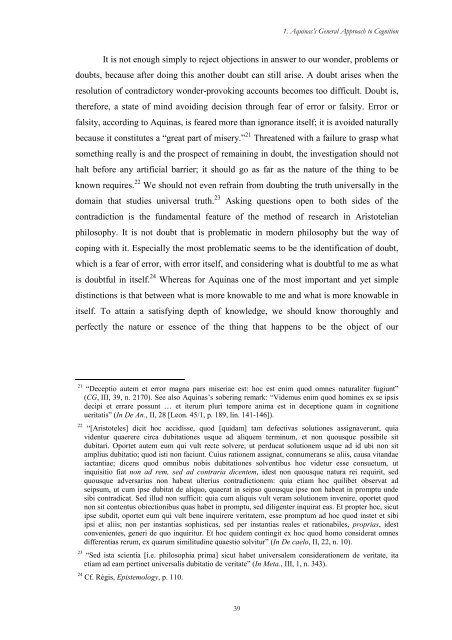

1. <strong>Aquinas</strong>’s General Approach <strong>to</strong> Cognition<br />

It is not enough simply <strong>to</strong> reject objections in answer <strong>to</strong> our wonder, problems or<br />

doubts, because after doing this ano<strong>the</strong>r doubt can still arise. A doubt arises when <strong>the</strong><br />

resolution of contradic<strong>to</strong>ry wonder-provoking accounts becomes <strong>to</strong>o difficult. Doubt is,<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore, a state of mind avoiding decision through fear of error or falsity. Error or<br />

falsity, according <strong>to</strong> <strong>Aquinas</strong>, is feared more than ignorance itself; it is avoided naturally<br />

because it constitutes a “great part of misery.” 21 Threatened with a failure <strong>to</strong> grasp what<br />

something really is and <strong>the</strong> prospect of remaining in doubt, <strong>the</strong> investigation should not<br />

halt before any artificial barrier; it should go as far as <strong>the</strong> nature of <strong>the</strong> thing <strong>to</strong> be<br />

known requires. 22 We should not even refrain <strong>from</strong> doubting <strong>the</strong> truth universally in <strong>the</strong><br />

domain that studies universal truth. 23 Asking questions open <strong>to</strong> both sides of <strong>the</strong><br />

contradiction is <strong>the</strong> fundamental feature of <strong>the</strong> method of research in Aris<strong>to</strong>telian<br />

philosophy. It is not doubt that is problematic in modern philosophy but <strong>the</strong> way of<br />

coping with it. Especially <strong>the</strong> most problematic seems <strong>to</strong> be <strong>the</strong> identification of doubt,<br />

which is a fear of error, with error itself, and considering what is doubtful <strong>to</strong> me as what<br />

is doubtful in itself. 24 Whereas for <strong>Aquinas</strong> one of <strong>the</strong> most important and yet simple<br />

distinctions is that between what is more knowable <strong>to</strong> me and what is more knowable in<br />

itself. To attain a satisfying depth of knowledge, we should know thoroughly and<br />

perfectly <strong>the</strong> nature or essence of <strong>the</strong> thing that happens <strong>to</strong> be <strong>the</strong> object of our<br />

21 “Deceptio autem et error magna pars miseriae est: hoc est enim quod omnes naturaliter fugiunt”<br />

(CG, III, 39, n. 2170). See also <strong>Aquinas</strong>’s sobering remark: “Videmus enim quod homines ex se ipsis<br />

decipi et errare possunt … et iterum pluri tempore anima est in deceptione quam in cognitione<br />

ueritatis” (In De An., II, 28 [Leon. 45/1, p. 189, lin. 141-146]).<br />

22 “[Aris<strong>to</strong>teles] dicit hoc accidisse, quod [quidam] tam defectivas solutiones assignaverunt, quia<br />

videntur quaerere circa dubitationes usque ad aliquem terminum, et non quousque possibile sit<br />

dubitari. Oportet autem eum qui vult recte solvere, ut perducat solutionem usque ad id ubi non sit<br />

amplius dubitatio; quod isti non faciunt. Cuius rationem assignat, connumerans se aliis, causa vitandae<br />

iactantiae; dicens quod omnibus nobis dubitationes solventibus hoc videtur esse consuetum, ut<br />

inquisitio fiat non ad rem, sed ad contraria dicentem, idest non quousque natura rei requirit, sed<br />

quousque adversarius non habeat ulterius contradictionem: quia etiam hoc quilibet observat ad<br />

seipsum, ut cum ipse dubitat de aliquo, quaerat in seipso quousque ipse non habeat in promptu unde<br />

sibi contradicat. Sed illud non sufficit: quia cum aliquis vult veram solutionem invenire, oportet quod<br />

non sit contentus obiectionibus quas habet in promptu, sed diligenter inquirat eas. Et propter hoc, sicut<br />

ipse subdit, oportet eum qui vult bene inquirere veritatem, esse promptum ad hoc quod instet et sibi<br />

ipsi et aliis; non per instantias sophisticas, sed per instantias reales et rationabiles, proprias, idest<br />

convenientes, generi de quo inquiritur. Et hoc quidem contingit ex hoc quod homo considerat omnes<br />

differentias rerum, ex quarum similitudine quaestio solvitur” (In De caelo, II, 22, n. 10).<br />

23 “Sed ista scientia [i.e. philosophia prima] sicut habet universalem considerationem de veritate, ita<br />

etiam ad eam pertinet universalis dubitatio de veritate” (In Meta., III, 1, n. 343).<br />

24 Cf. Régis, Epistemology, p. 110.