Predictors of Bullying and Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence

Predictors of Bullying and Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence

Predictors of Bullying and Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

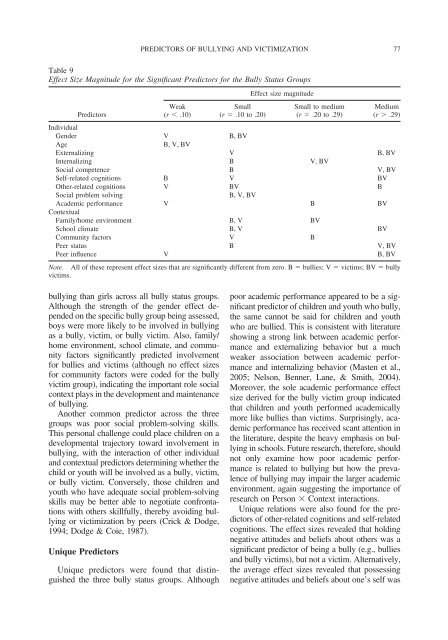

Table 9<br />

Effect Size Magnitude for the Significant <strong>Predictors</strong> for the Bully Status Groups<br />

<strong>Predictors</strong><br />

bully<strong>in</strong>g than girls across all bully status groups.<br />

Although the strength <strong>of</strong> the gender effect depended<br />

on the specific bully group be<strong>in</strong>g assessed,<br />

boys were more likely to be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> bully<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as a bully, victim, or bully victim. Also, family/<br />

home environment, school climate, <strong>and</strong> community<br />

factors significantly predicted <strong>in</strong>volvement<br />

for bullies <strong>and</strong> victims (although no effect sizes<br />

for community factors were coded for the bully<br />

victim group), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g the important role social<br />

context plays <strong>in</strong> the development <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance<br />

<strong>of</strong> bully<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Another common predictor across the three<br />

groups was poor social problem-solv<strong>in</strong>g skills.<br />

This personal challenge could place children on a<br />

developmental trajectory toward <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong><br />

bully<strong>in</strong>g, with the <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong> other <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

<strong>and</strong> contextual predictors determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whether the<br />

child or youth will be <strong>in</strong>volved as a bully, victim,<br />

or bully victim. Conversely, those children <strong>and</strong><br />

youth who have adequate social problem-solv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

skills may be better able to negotiate confrontations<br />

with others skillfully, thereby avoid<strong>in</strong>g bully<strong>in</strong>g<br />

or victimization by peers (Crick & Dodge,<br />

1994; Dodge & Coie, 1987).<br />

Unique <strong>Predictors</strong><br />

Unique predictors were found that dist<strong>in</strong>guished<br />

the three bully status groups. Although<br />

PREDICTORS OF BULLYING AND VICTIMIZATION<br />

Weak<br />

(r .10)<br />

Small<br />

(r .10 to .20)<br />

Effect size magnitude<br />

Small to medium<br />

(r .20 to .29)<br />

Medium<br />

(r .29)<br />

Individual<br />

Gender V B, BV<br />

Age B, V, BV<br />

Externaliz<strong>in</strong>g V B, BV<br />

Internaliz<strong>in</strong>g B V, BV<br />

Social competence B V, BV<br />

Self-related cognitions B V BV<br />

Other-related cognitions V BV B<br />

Social problem solv<strong>in</strong>g B, V, BV<br />

Academic performance<br />

Contextual<br />

V B BV<br />

Family/home environment B, V BV<br />

School climate B, V BV<br />

Community factors V B<br />

Peer status B V, BV<br />

Peer <strong>in</strong>fluence V B, BV<br />

Note. All <strong>of</strong> these represent effect sizes that are significantly different from zero. B bullies; V victims; BV bully<br />

victims.<br />

poor academic performance appeared to be a significant<br />

predictor <strong>of</strong> children <strong>and</strong> youth who bully,<br />

the same cannot be said for children <strong>and</strong> youth<br />

who are bullied. This is consistent with literature<br />

show<strong>in</strong>g a strong l<strong>in</strong>k between academic performance<br />

<strong>and</strong> externaliz<strong>in</strong>g behavior but a much<br />

weaker association between academic performance<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternaliz<strong>in</strong>g behavior (Masten et al.,<br />

2005; Nelson, Benner, Lane, & Smith, 2004).<br />

Moreover, the sole academic performance effect<br />

size derived for the bully victim group <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

that children <strong>and</strong> youth performed academically<br />

more like bullies than victims. Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, academic<br />

performance has received scant attention <strong>in</strong><br />

the literature, despite the heavy emphasis on bully<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> schools. Future research, therefore, should<br />

not only exam<strong>in</strong>e how poor academic performance<br />

is related to bully<strong>in</strong>g but how the prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> bully<strong>in</strong>g may impair the larger academic<br />

environment, aga<strong>in</strong> suggest<strong>in</strong>g the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

research on Person Context <strong>in</strong>teractions.<br />

Unique relations were also found for the predictors<br />

<strong>of</strong> other-related cognitions <strong>and</strong> self-related<br />

cognitions. The effect sizes revealed that hold<strong>in</strong>g<br />

negative attitudes <strong>and</strong> beliefs about others was a<br />

significant predictor <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g a bully (e.g., bullies<br />

<strong>and</strong> bully victims), but not a victim. Alternatively,<br />

the average effect sizes revealed that possess<strong>in</strong>g<br />

negative attitudes <strong>and</strong> beliefs about one’s self was<br />

77