Antioxidant activities in tropical marine macroalgae - CINVESTAV ...

Antioxidant activities in tropical marine macroalgae - CINVESTAV ...

Antioxidant activities in tropical marine macroalgae - CINVESTAV ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

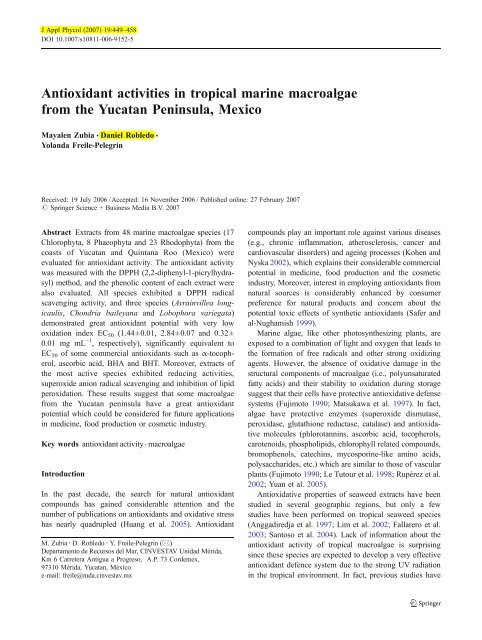

J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

DOI 10.1007/s10811-006-9152-5<br />

<strong>Antioxidant</strong> <strong>activities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>tropical</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>macroalgae</strong><br />

from the Yucatan Pen<strong>in</strong>sula, Mexico<br />

Mayalen Zubia & Daniel Robledo &<br />

Yolanda Freile-Pelegr<strong>in</strong><br />

Received: 19 July 2006 /Accepted: 16 November 2006 / Published onl<strong>in</strong>e: 27 February 2007<br />

# Spr<strong>in</strong>ger Science + Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Media B.V. 2007<br />

Abstract Extracts from 48 mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>macroalgae</strong> species (17<br />

Chlorophyta, 8 Phaeophyta and 23 Rhodophyta) from the<br />

coasts of Yucatan and Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo (Mexico) were<br />

evaluated for antioxidant activity. The antioxidant activity<br />

was measured with the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrasyl)<br />

method, and the phenolic content of each extract were<br />

also evaluated. All species exhibited a DPPH radical<br />

scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity, and three species (Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis,<br />

Chondria baileyana and Lobophora variegata)<br />

demonstrated great antioxidant potential with very low<br />

oxidation <strong>in</strong>dex EC 50 (1.44±0.01, 2.84±0.07 and 0.32±<br />

0.01 mg mL −1 , respectively), significantly equivalent to<br />

EC50 of some commercial antioxidants such as α-tocopherol,<br />

ascorbic acid, BHA and BHT. Moreover, extracts of<br />

the most active species exhibited reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activities</strong>,<br />

superoxide anion radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>hibition of lipid<br />

peroxidation. These results suggest that some <strong>macroalgae</strong><br />

from the Yucatan pen<strong>in</strong>sula have a great antioxidant<br />

potential which could be considered for future applications<br />

<strong>in</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e, food production or cosmetic <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

Key words antioxidant activity . <strong>macroalgae</strong><br />

Introduction<br />

In the past decade, the search for natural antioxidant<br />

compounds has ga<strong>in</strong>ed considerable attention and the<br />

number of publications on antioxidants and oxidative stress<br />

has nearly quadrupled (Huang et al. 2005). <strong>Antioxidant</strong><br />

M. Zubia : D. Robledo : Y. Freile-Pelegr<strong>in</strong> (*)<br />

Departamento de Recursos del Mar, <strong>CINVESTAV</strong> Unidad Mérida,<br />

Km 6 Carretera Antigua a Progreso, A.P. 73 Cordemex,<br />

97310 Mérida, Yucatan, México<br />

e-mail: freile@mda.c<strong>in</strong>vestav.mx<br />

compounds play an important role aga<strong>in</strong>st various diseases<br />

(e.g., chronic <strong>in</strong>flammation, atherosclerosis, cancer and<br />

cardiovascular disorders) and age<strong>in</strong>g processes (Kohen and<br />

Nyska 2002), which expla<strong>in</strong>s their considerable commercial<br />

potential <strong>in</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e, food production and the cosmetic<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry. Moreover, <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> employ<strong>in</strong>g antioxidants from<br />

natural sources is considerably enhanced by consumer<br />

preference for natural products and concern about the<br />

potential toxic effects of synthetic antioxidants (Safer and<br />

al-Nughamish 1999).<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e algae, like other photosynthesiz<strong>in</strong>g plants, are<br />

exposed to a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of light and oxygen that leads to<br />

the formation of free radicals and other strong oxidiz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

agents. However, the absence of oxidative damage <strong>in</strong> the<br />

structural components of <strong>macroalgae</strong> (i.e., polyunsaturated<br />

fatty acids) and their stability to oxidation dur<strong>in</strong>g storage<br />

suggest that their cells have protective antioxidative defense<br />

systems (Fujimoto 1990; Matsukawa et al. 1997). In fact,<br />

algae have protective enzymes (superoxide dismutase,<br />

peroxidase, glutathione reductase, catalase) and antioxidative<br />

molecules (phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s, ascorbic acid, tocopherols,<br />

carotenoids, phospholipids, chlorophyll related compounds,<br />

bromophenols, catech<strong>in</strong>s, mycospor<strong>in</strong>e-like am<strong>in</strong>o acids,<br />

polysaccharides, etc.) which are similar to those of vascular<br />

plants (Fujimoto 1990; Le Tutour et al. 1998; Rupérez et al.<br />

2002; Yuan et al. 2005).<br />

Antioxidative properties of seaweed extracts have been<br />

studied <strong>in</strong> several geographic regions, but only a few<br />

studies have been performed on <strong>tropical</strong> seaweed species<br />

(Anggadiredja et al. 1997; Lim et al. 2002; Fallarero et al.<br />

2003; Santoso et al. 2004). Lack of <strong>in</strong>formation about the<br />

antioxidant activity of <strong>tropical</strong> <strong>macroalgae</strong> is surpris<strong>in</strong>g<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce these species are expected to develop a very effective<br />

antioxidant defence system due to the strong UV radiation<br />

<strong>in</strong> the <strong>tropical</strong> environment. In fact, previous studies have

450 J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

demonstrated that UV radiation <strong>in</strong>duces the promotion of<br />

antioxidant defense <strong>in</strong> <strong>macroalgae</strong> (Aguilera et al. 2002;<br />

Bischof et al. 2002).IntheGulfofMexicoandCaribbean<br />

coast of Yucatan and Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo, there are numerous species<br />

of<strong>macroalgae</strong>exposedtohighsolar irradiation and some of<br />

them have never been studied for their antioxidant <strong>activities</strong>.<br />

The present study evaluated the antioxidative potential<br />

of 48 species of <strong>macroalgae</strong> from the coasts of Yucatan and<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo (Mexico) by measur<strong>in</strong>g the 2,2-diphenyl-1picrylhydrasyl<br />

(DPPH) radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity and total<br />

content of phenolic compounds <strong>in</strong> alcoholic extracts.<br />

<strong>Antioxidant</strong> <strong>activities</strong> have been attributed to various<br />

reactions and mechanisms: prevention of cha<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation,<br />

b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of transition metal ion catalysts, reductive capacity,<br />

radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g, etc. (Frankel and Meyer 2000; Huang<br />

et al. 2005). Therefore, <strong>in</strong> order to better understand the<br />

antioxidant processes <strong>in</strong>volved, the specific antioxidative<br />

<strong>activities</strong> of the most active extracts were also characterized,<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g different biochemical methods: reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity,<br />

superoxide anion scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity and <strong>in</strong>hibition of<br />

lipid peroxidation.<br />

Materials and methods<br />

Collection and preparation of algal extracts<br />

Forty-eight species of <strong>macroalgae</strong> were collected from the<br />

Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean coast of Yucatan and<br />

Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo (Fig. 1) between October 2005 and February<br />

2006. Once harvested, <strong>macroalgae</strong> were stored <strong>in</strong> plastic<br />

Fig. 1 Map of Yucatan pen<strong>in</strong>sula <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g the collect<strong>in</strong>g sites <strong>in</strong><br />

Yucatan (1 Telchac; 2 Dzilam de Bravo) and Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo (3 Cancún;<br />

4 Playa del Carmen; 5 Tulum) coasts<br />

bags and placed on ice for transport to the laboratory.<br />

Voucher specimens of all species were pressed and stored <strong>in</strong><br />

4% formol for identification accord<strong>in</strong>g to Wynne (2005).<br />

Samples were washed thoroughly with fresh water to<br />

remove salts, sand and epiphytes, and stored at −20°C.<br />

Entire plants of each <strong>macroalgae</strong> were lyophilized and<br />

milled <strong>in</strong>to powder before extraction. Lyophilized samples<br />

(5 g) were extracted twice with 75 mL of dichloromethanol:<br />

methanol (2:1) dur<strong>in</strong>g 20 h. Extracts were comb<strong>in</strong>ed,<br />

filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to 10 mL,<br />

and stored at −20°C.<br />

Determ<strong>in</strong>ation of phenolic content<br />

Total content of phenolic compounds of algal extracts was<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed spectrophotometrically us<strong>in</strong>g Fol<strong>in</strong>-Ciocalteu<br />

reagent accord<strong>in</strong>g to the method described <strong>in</strong> Lim et al.<br />

(2002). First, extracts (0.3 mL) were diluted with methanol<br />

(2.7 mL). Aliquots of the diluted extracts (0.1 mL) were<br />

transferred <strong>in</strong>to the test tubes; 2.9 mL of distilled water<br />

and 0.5 mL of Fol<strong>in</strong>-Ciocalteu reagent were added. After<br />

10 m<strong>in</strong>, 1.5 mL of 20% sodium carbonate solution was<br />

added and the mixture was mixed thoroughly and allowed<br />

to stand at room temperature <strong>in</strong> the dark for 1 h. Absorbance<br />

was measured at 725 nm and total content of<br />

phenolic compounds was calculated based on a standard<br />

curve of phlorogluc<strong>in</strong>ol and expressed <strong>in</strong> % of dry<br />

weight.<br />

DPPH radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrasyl) radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<br />

activity was determ<strong>in</strong>ed accord<strong>in</strong>g to the method of Brand-<br />

Williams et al. (1995). Briefly, 100 μL of each extract at<br />

various dilutions (pure, 0.5, 0.25, etc., depend<strong>in</strong>g on the<br />

activity of each extract) were mixed with 3.9 mL of a DPPH<br />

solution (25 mg L −1 ) prepared daily. Due to color <strong>in</strong>tensity<br />

of the extracts, it was necessary to prepare a blank of 100 μL<br />

of each extract at various dilutions added to 3.9 mL of<br />

methanol. The reaction was complete after 2 h <strong>in</strong> the dark at<br />

room temperature, and the absorbance was read at 515 nm.<br />

DPPH versus absorbance was calculated by l<strong>in</strong>ear regression<br />

(n=8; r=0.99): [DPPH]=36.76 (Abs+0.0044). These<br />

values were plotted aga<strong>in</strong>st percentage of DPPH (% DPPH)<br />

to estimate 50% reduction of its <strong>in</strong>itial value (EC50;<br />

efficient concentration, also called oxidation <strong>in</strong>dex). Every<br />

sample was done <strong>in</strong> triplicate and mean values were<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed to calculated the EC50. Positive controls such as<br />

ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene)<br />

and BHA (butylated hydroxyanisole) were also<br />

measured, and the means of the EC50 of each control were<br />

calculated from five measurements.

J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458 451<br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity of the extracts was evaluated accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to the method of Oyaizu (1986) <strong>in</strong> Yen and Chen (1995).<br />

This assay measures the total antioxidant capacity of an<br />

extract evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the redox potentials of the compounds.<br />

Extract samples (0.5 mL) at two different concentrations<br />

(0.1 and 0.5 mg mL −1 ) were mixed with phosphate buffer<br />

(1.25 mL, 0.2 M, pH 6.6) and potassium ferricyanide (K3Fe<br />

(CN)6; 1.25 mL, 1%) and <strong>in</strong>cubated at 50°C for 20 m<strong>in</strong>,<br />

cooled and mixed with 1.25 mL of trichloroacetic acid<br />

(10%), and 1.25 mL of this mixture was transferred to other<br />

test tubes <strong>in</strong> which distilled water (1.25 mL) and<br />

FeCl 3.6H 2O (0.25 mL, 0.1%) were added. The mixture<br />

was centrifuged and kept at room temperature for 10 m<strong>in</strong><br />

before read<strong>in</strong>g the absorbance at 700 nm. Every sample and<br />

positive controls (ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, BHT and<br />

BHA) were done <strong>in</strong> triplicate.<br />

Superoxide anion radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

Superoxide anion is one of the most effective free radical,<br />

implicated <strong>in</strong> cell damage as precursors of ma<strong>in</strong>ly reactive<br />

oxygen species, contribut<strong>in</strong>g to the pathological process of<br />

many diseases. The superoxide anion scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity of<br />

the extracts was determ<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g a non enzymatic system<br />

described <strong>in</strong> Lim et al. (2002). All reagents were prepared<br />

with Tris-HCl buffer (16 mM, pH 8.0). In the test tubes,<br />

1 mL of 234 μM NADH, 1 mL of 150 μM nitroblue<br />

tetrazolium (NBT) and 0.2 mL of the seaweed extracts at<br />

three concentrations (0.1, 0.5 and 1 mg mL −1 ) were mixed<br />

together with 0.8 mL of 37.5 μM phenaz<strong>in</strong>e methosulfate<br />

(PMS); after 5 m<strong>in</strong> the absorbance was measured at<br />

560 nm. The same mixture without sample extract was<br />

used as control, and blanks for each extract were prepared<br />

without PMS. Every sample and positive controls (acid<br />

ascorbic, α-tocopherol and BHT) were done <strong>in</strong> triplicate.<br />

Inhibition of lipid oxidation<br />

Oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids <strong>in</strong> biological membranes<br />

leads to the formation of lipid radicals and destruction of<br />

lipid membranes. <strong>Antioxidant</strong>s can disrupt the free-radical<br />

cha<strong>in</strong> reaction by donat<strong>in</strong>g their hydrogen to fatty acids<br />

radicals to term<strong>in</strong>ate cha<strong>in</strong> reaction. The ferric thiocyanate<br />

(FTC) method of Larrauri et al. (1996) <strong>in</strong> Sanchez-Moreno<br />

et al. (1999) used a l<strong>in</strong>oleic acid model to evaluate <strong>in</strong>hibition<br />

of lipid oxidation. Sample extracts (0.5 mL, 0.5 mg mL −1 )<br />

were mixed with an emulsion of 2.51% l<strong>in</strong>oleic acid <strong>in</strong><br />

absolute ethanol (0.5 mL), 0.05 M phosphate buffer pH 7<br />

(1 mL) and distilled water (0.5 mL) <strong>in</strong> a screw capped tube,<br />

shaken and <strong>in</strong>cubated <strong>in</strong> an oven at 40°C <strong>in</strong> the dark. The<br />

same mixture without sample extract was used as control. At<br />

different time <strong>in</strong>tervals (0–10 days), 0.1 mL of each tube was<br />

transferred to the other tube where 9.7 mL of 75% ethanol<br />

and 0.1 mL of 30% ammonium thiocyanate together with<br />

0.1 mL of 0.02 M ferrous chloride <strong>in</strong> 3.5% hydrochloric acid<br />

were added; after 3 m<strong>in</strong>, the absorbance was measured at<br />

500 nm. Every sample and positive controls (α-tocopherol,<br />

BHT and BHA) were done <strong>in</strong> triplicate.<br />

Statistical analysis<br />

All statistical analyses were performed with Statistica 6<br />

software. Data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk’s<br />

test) and subjected to Bartlett’s test to verify the homogeneity<br />

of variances groups. One-way analysis of variance<br />

(ANOVA) was used to compare antioxidant activity<br />

between extracts after transformation of data if necessary<br />

and post-hoc test (Tukey HSD) was performed when data<br />

showed significant differences (p

452 J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

Table 1 Phenolic content of the species collected <strong>in</strong> Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo 1 and the Yucatan 2 coasts of Mexico<br />

Species Locality Phenolic content (% dry wt)<br />

Chlorophyta<br />

Acetabularia schenckii K. Möbius Cancun 1<br />

Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis (Kütz<strong>in</strong>g) G. Murray & Boodle Puerto Morelos 1<br />

Caulerpa ashmeadii Harvey Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Caulerpa cupressoides (H. West <strong>in</strong> Vahl) C. Agardh Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Caulerpa paspaloides (Bory de Sa<strong>in</strong>t-V<strong>in</strong>cent) Greville Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Caulerpa prolifera (Forsskål) J.V. Lamouroux Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Caulerpa sertularioides (S.G. Gmel<strong>in</strong>) M. Howe Tulum 1<br />

Caulerpa taxifolia (H. West <strong>in</strong> Vahl) C. Agardh Tulum 1<br />

Cladophora prolifera (Roth) Kütz<strong>in</strong>g Playa de Carmen 1<br />

Cladophora vagabunda (L<strong>in</strong>naeus) Hoek Cancun 1<br />

Codium decorticatum (Woodward) M. Howe Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Enteromorpha <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>alis (L<strong>in</strong>naeus) Nees Cancun 1<br />

Halimeda monile (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux Telchac 2<br />

Halimeda tuna (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux Telchac 2<br />

Penicillus dumetosus (J.V. Lamouroux) Bla<strong>in</strong>ville Telchac 2<br />

Penicillus pyriformis A. Gepp & E.S. Gepp Telchac 2<br />

Udotea conglut<strong>in</strong>ata (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Phaeophyta<br />

Dictyota cervicornis Kütz<strong>in</strong>g Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Dictyota ciliolata Sonder ex Kütz<strong>in</strong>g Tulum 1<br />

Dictyota crenulata J. Agardh Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Lobophora variegata (J.V. Lamouroux) Womersley ex E.C. Oliveira Telchac 2<br />

Pad<strong>in</strong>a gymnospora (Kütz<strong>in</strong>g) Sonder Playa de Carmen 1<br />

Sargassum pteropleuron Grunow Telchac 2<br />

Sargassum ramifolium Kütz<strong>in</strong>g Telchac 2<br />

Turb<strong>in</strong>aria tricostata E.S. Barton Tulum 1<br />

Rhodophyta<br />

Acanthophora spicifera (M. Vahl) Børgesen Telchac 2<br />

Bryothamnion triquetrum (S.G. Gmel<strong>in</strong>) M. Howe Tulum 1<br />

Ceramium nitens (C. Agardh) J. Agardh Tulum 1<br />

Champia salicornioides Harvey Cancun 1<br />

Chondria atropurpurea Harvey Tulum 1<br />

Chondria baileyana (Montagne) Harvey Cancun 1<br />

Chondrophycus papillosus (C. Agardh) Garbary & J.T. Harper Tulum 1<br />

Chondrophycus poiteaui (J.V. Lamouroux) K.W. Nam Puerto Morelos 1<br />

Digenea simplex (Wulfen) C. Agardh Telchac 2<br />

Eucheuma isiforme (C. Agardh) J. Agardh Telchac 2<br />

Gracilaria bursa-pastoris (S.G. Gmel<strong>in</strong>) P.C. Silva Telchac 2<br />

Gracilaria caudata J. Agardh Telchac 2<br />

Gracilaria cornea J. Agardh Telchac 2<br />

Gracilaria cyl<strong>in</strong>drica Børgesen Telchac 2<br />

Gracilaria tikvahiae McLachlan Telchac 2<br />

Gracilariopsis tenuifrons (C.J. Bird & E.C. Oliveira) Fredericq & Hommersand Playa de Carmen 1<br />

Halymenia floresii (Clemente & Rubio) C. Agardh Telchac 2<br />

Heterosiphonia gibbesii (Harvey) Falkenberg Playa de Carmen 1<br />

Hypnea sp<strong>in</strong>ella (C. Agardh) Kütz<strong>in</strong>g Playa de Carmen 1<br />

Laurencia <strong>in</strong>tricata J.V. Lamouroux Dzilam de Bravo 2<br />

Laurencia obtusa (Hudson) J.V. Lamouroux Tulum 1<br />

Liagora ceranoides J.V. Lamouroux Tulum 1<br />

Nemalion helm<strong>in</strong>thoides (Velley) Batters Playa de Carmen 1<br />

0.76±0.05<br />

3.36±0.05<br />

1.42±0.11<br />

4.36±0.31<br />

4.26±0.21<br />

8.13±0.52<br />

6.48±0.17<br />

6.60±0.23<br />

1.95±0.12<br />

1.02±0.08<br />

0.54±0.04<br />

1.42±0.11<br />

0.47±0.00<br />

1.70±0.02<br />

2.24±0.06<br />

1.35±0.16<br />

2.04±0.21<br />

5.55±0.23<br />

5.53±0.09<br />

1.99±0.06<br />

29.18±0.32<br />

5.58±0.30<br />

0.76±0.04<br />

0.95±0.10<br />

1.05±0.08<br />

1.19±0.09<br />

1.55±0.21<br />

1.92±0.07<br />

2.64±0.33<br />

3.21±0.40<br />

7.30±0.29<br />

1.34±0.17<br />

1.77±0.10<br />

0.64±0.08<br />

0.36±0.08<br />

0.38±0.01<br />

0.34±0.03<br />

0.50±0.12<br />

0.41±0.03<br />

0.36±0.02<br />

2.04±0.13<br />

1.03±0.08<br />

3.45±0.36<br />

0.67±0.06<br />

2.51±0.10<br />

4.17±0.12<br />

0.90±0.10<br />

1.87±0.03

J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458 453<br />

Fig. 2 DPPH radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<br />

activity expressed <strong>in</strong> oxidation<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex EC 50 given <strong>in</strong> mg<br />

mL −1 (mean ± SD; n=3) for<br />

Chlorophyta extracts and controls<br />

(ascorbic acid, BHA, BHT<br />

and α-tocopherol). Bars represent<br />

standard deviations. Significant<br />

differences are <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

by different letters as determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by Tukey HSD test<br />

(p

454 J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

Fig. 4 DPPH radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<br />

activity expressed <strong>in</strong> oxidation<br />

<strong>in</strong>dex EC 50 given <strong>in</strong> mg<br />

mL −1 (mean ± SD; n=3) for<br />

Rhodophyta extracts and controls<br />

(ascorbic acid, BHA, BHT<br />

and α-tocopherol). Bars represent<br />

standard deviations. Significant<br />

differences are <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

by different letters as determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by Tukey HSD test<br />

(p

J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458 455<br />

The most active species of Phaeophyta <strong>in</strong> our study<br />

(Lobophora variegata, Pad<strong>in</strong>a gymnospora and Dictyota<br />

cervicornis) belong to the same family, the Dictyotaceae,<br />

which has been extensively studied for its wide variety of<br />

bioactive compounds (e.g., terpenoids and acetogen<strong>in</strong>s) that<br />

conferred a very effective antiherbivore defense system and<br />

various biological <strong>activities</strong> (Ballant<strong>in</strong>e et al. 1987; Duran<br />

et al. 1997; Amsler and Fairhead 2006). In previous studies,<br />

low antioxidant <strong>activities</strong> have been measured <strong>in</strong> other<br />

species of Dictyotaceae (Yan et al. 1998; Santoso et al.<br />

2004; Cavas and Yurdakoc 2005), except <strong>in</strong> Spatoglossum<br />

pacificum (Matsukawa et al. 1997).<br />

The genus Sargassum also exhibited relatively high DPPH<br />

radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activities</strong> with an oxidation <strong>in</strong>dex EC 50<br />

rang<strong>in</strong>gfrom6.64to7.14mgmL −1 . The genus Sargassum has<br />

been studied extensively show<strong>in</strong>g high antioxidant potential<br />

<strong>in</strong> vitro (Anggadiredja et al. 1997; Matsukawa et al. 1997;<br />

Yan et al. 1998; Lim et al. 2002; Santoso et al. 2004; Heo<br />

et al. 2005; Kimetal.2005; Parketal.2005; Connan et al.<br />

2006) and <strong>in</strong> vivo (Mori et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2003).<br />

Rhodophyta<br />

All species of Rhodophyta showed antioxidant <strong>activities</strong><br />

with EC 50 from 2.84 to 77.71 mg mL −1 (Fig. 4). Chondria<br />

baileyana had the highest antioxidant activity with the<br />

lowest EC50 (2.84±0.07 mg mL −1 ) significantly equivalent<br />

to EC 50 of all commercial antioxidants tested as well as the<br />

highest phenolic content (7.30±0.29% dry wt) (Table 1).<br />

Chondria atropurpurea also exhibited a relatively high<br />

antioxidant activity (10.43±0.11 mg mL −1 ). In fact, the<br />

genus Chondria is a source of various bioactive compounds<br />

(e.g., terpenoids, novel am<strong>in</strong>o-acids, cyclic polysulfides and<br />

<strong>in</strong>doles) that have shown anthelm<strong>in</strong>tic (Davyt et al. 1998)<br />

and antibiotic <strong>activities</strong> (Ballant<strong>in</strong>e et al. 1987). Chondria<br />

crassicaulis and C. tenuissima have not shown a high<br />

antioxidant activity (Huang and Wang 2004) when compared<br />

to our results, but they were collected <strong>in</strong> temperate<br />

environments.<br />

Various species from the order Ceramiales also exhibited<br />

relatively high DPPH radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activities</strong>: Heterosiphonia<br />

gibbesii (8.15±0.10 mg mL −1 ), Acanthophora<br />

spicifera (12.50±0.24 mg mL −1 ), Bryothamnion triquetrum<br />

(12.89±0.51 mg mL −1 ) and Ceramium nitens (13.89±<br />

0.07 mg mL −1 ). Other studies have shown antioxidant<br />

activity <strong>in</strong> Polysiphonia urceolata and P. morrowii (Fujimoto<br />

1990), Bryothamnion triquetrum (Fallarero et al. 2003),<br />

and Rhodomela confervoides (Huang and Wang 2004). On<br />

the other hand, although the genus Laurencia and<br />

Chondrophycus represent a prolific source of secondary<br />

metabolites (Blunt et al. 2005), their antioxidant activity<br />

was not comparable to other species from the order<br />

Ceramiales. This observation is <strong>in</strong> accordance with<br />

previous studies where Laurencia species have not shown<br />

high antioxidant activity (Anggadiredja et al. 1997; Yan et al.<br />

1998; Takamatsu et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2005). Gracilaria<br />

species exhibited very low antioxidant <strong>activities</strong> (28.94 to<br />

72.51 mg mL −1 ), although Yan et al. (1998) reportedaDPPH<br />

radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity around 40% for G. verrucosa<br />

methanolic extract, though results are not comparable<br />

because of the different methods used.<br />

No discernable pattern of antioxidant activity could be<br />

detected with<strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle algal order or division. It is difficult<br />

to compare the antioxidant activity between all the above<br />

species s<strong>in</strong>ce they were collected at different periods and<br />

localities. In fact, the production of antioxidant compounds,<br />

like phenolics, is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by several factors: extr<strong>in</strong>sic<br />

(herbivory pressure, irradiance, depth, sal<strong>in</strong>ity, nutrients,<br />

etc.), and <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic (type, age and reproductive stage) (see<br />

review <strong>in</strong> Connan et al. 2006). Therefore, antioxidant<br />

activity of seaweeds could be subject to great <strong>in</strong>traspecific<br />

variation, even at very small scales (Connan et al. 2006),<br />

with <strong>in</strong>tra-thallus variations <strong>in</strong> antioxidant activity hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

been shown for Ascophyllum nodosum. Moreover, it is very<br />

difficult to compare <strong>macroalgae</strong> antioxidant <strong>activities</strong> with<br />

other studies because each author used different extraction<br />

protocols, assay methods and units. This is why the use of<br />

the oxidation <strong>in</strong>dex EC 50 represents a valuable tool for<br />

comparisons.<br />

Antioxidative <strong>activities</strong> of the most active species<br />

Our study showed a very strong antioxidant potential <strong>in</strong> three<br />

species of <strong>macroalgae</strong>: Lobophora variegata (0.32±0.01 mg<br />

mL −1 ), Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis (1.44±0.01 mg mL −1 )and<br />

Chondria baileyana (2.84±0.07 mg mL −1 ). In fact, they are<br />

equivalent to the <strong>activities</strong> of some commercial antioxidants.<br />

Moreover, reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activities</strong> of the extracts at two concentrations<br />

(0.1 and 0.5 mg mL −1 ) confirmed the results of the<br />

DPPH method: L. variegata had the greatest reduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

activity, and its activity <strong>in</strong>creased as extract concentration<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased (Fig. 5a). The highest levels of reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

were measured for BHA, ascorbic acid and BHT, but the one<br />

from L. variegata is significantly higher than those of<br />

commercial antioxidant α-tocopherol. Most of the published<br />

studies with <strong>macroalgae</strong> have demonstrated reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

(Karawita et al. 2005; Kudaetal.2005; Yuanetal.2005;<br />

Senevirathne et al. 2006).<br />

Superoxide anion radical O 2 scaveng<strong>in</strong>g activity of<br />

the extracts are summarized <strong>in</strong> Fig. 5b. Highest values were<br />

for ascorbic acid and L. variegata (71.84% and 70.46% for<br />

1 mg mL −1 , respectively) which confirm the strong<br />

antioxidant activity of L. variegata as was the case with<br />

various species of Phaeophyta (Siriwardhana et al. 2003;<br />

Karawita et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2005; Kuda et al. 2005;<br />

Senevirathne et al. 2006), but only Ecklonia cava compares

456 J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

Fig. 5 <strong>Antioxidant</strong> activity of<br />

A. longicaulis, C. baileyana and<br />

L. variegata extracts compared<br />

to commercial antioxidants<br />

(ascorbic acid, BHA, BHT and<br />

α-tocopherol). a Reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity<br />

(absorbance at 700 nm); b<br />

superoxide anion radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<br />

activity (%). Bars represent<br />

standard deviations.<br />

Significant differences are <strong>in</strong>dicated<br />

by different letters as<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed by Tukey HSD test<br />

(p

J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458 457<br />

the addition of algal extracts or commercial antioxidants<br />

was accompanied by a rapid <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> absorbance that<br />

reached 1.540 <strong>in</strong> 10 days (control). The <strong>in</strong>hibitory effect of<br />

C. baileyana at 0.5 mg mL −1 is equivalent to BHT and<br />

significantly higher than the effects of commercial antioxidants<br />

tested. A. longicaulis also showed <strong>in</strong>hibitory effect of<br />

lipid peroxidation, significantly higher than BHA and αtocopherol.<br />

In this assay, the antioxidant activity of L.<br />

variegata showed the lowest antioxidant activity; nevertheless,<br />

its <strong>in</strong>hibitory effect is equivalent to that of α-tocopherol.<br />

These data are <strong>in</strong> accordance with previous studies that have<br />

demonstrated the <strong>in</strong>hibition of lipid peroxidation by extracts<br />

from Rhodophyta (Athukorala et al. 2003; Yuanetal.2005),<br />

Phaeophyta (Lim et al. 2002; Siriwardhana et al. 2003;<br />

Karawita et al. 2005; Senevirathne et al. 2006) and<br />

Chlorophyta (Cavas and Yurdakoc 2005). Moreover, these<br />

results suggest that antioxidants from C. baileyana and A.<br />

longicaulis are more effective as cha<strong>in</strong> break<strong>in</strong>g molecules<br />

rather than reductors, whereas those of L. variegata have<br />

very good reductive capacity, but low cha<strong>in</strong> break<strong>in</strong>g<br />

capacity. In the future, identification of these molecules will<br />

be helpful to understand the different antioxidant mechanisms<br />

observed <strong>in</strong> this study.<br />

Conclusion<br />

This work represents the largest screen<strong>in</strong>g of antioxidant<br />

activity <strong>in</strong> <strong>tropical</strong> <strong>macroalgae</strong> to date. All species collected<br />

from the coasts of Qu<strong>in</strong>tana Roo and Yucatan showed<br />

antioxidant <strong>activities</strong>, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>tropical</strong> <strong>macroalgae</strong><br />

develop an effective antioxidant defense system which may<br />

reflect an adaptation to high solar radiation. This screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

emphasized the great antioxidant potential (free-radical,<br />

superoxide anion radical scaveng<strong>in</strong>g, reduc<strong>in</strong>g activity, and<br />

<strong>in</strong>hibition of lipid peroxidation) of three species: Lobophora<br />

variegata, Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis and Chondria baileyana.<br />

Identification of the antioxidant compounds of these extracts<br />

will lead to their evaluation <strong>in</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e, food production<br />

and cosmetic <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

Acknowledgments This research was f<strong>in</strong>anced by SAGARPA-<br />

CONACYT (Contract 2002-C01-1057). The authors thank J.L. God<strong>in</strong>ez<br />

for identification of the <strong>macroalgae</strong> species and C. Chávez and M.L.<br />

Zaldivar for technical assistance.<br />

References<br />

Aguilera J, Bischof K, Karsten U, Hanelt D, Wiencke C (2002)<br />

Seasonal variation <strong>in</strong> ecophysiological patterns <strong>in</strong> <strong>macroalgae</strong><br />

from an Arctic fjord. II. Pigment accumulation and biochemical<br />

defense systems aga<strong>in</strong>st light stress. Mar Biol 140:1087–1095<br />

Amsler CD, Fairhead VA (2006) Defensive and sensory chemical<br />

ecology of brown algae. Adv Bot Res 43:1–91<br />

Anggadiredja J, Andyani R, Hayati, Muawanah (1997) <strong>Antioxidant</strong><br />

activity of Sargassum polycystum (Phaeophyta) and Laurencia<br />

obtusa (Rhodophyta) from Seribu Islands. J Appl Phycol 9:477–479<br />

Athukorala Y, Lee KW, Song C, Ahn CB, Sh<strong>in</strong> TS, Cha YJ, Shahidi F,<br />

Jeon YJ (2003) Potential antioxidant activity of mar<strong>in</strong>e red alga<br />

Grateloupia filic<strong>in</strong>a extracts. J Food Lipids 10:251–265<br />

Ballant<strong>in</strong>e DL, Gerwick WH, Velez SM, Alexander E, Guevara P<br />

(1987) Antibiotic activity of lipid-soluble extracts from Caribbean<br />

mar<strong>in</strong>a algae. Hydrobiologia 151/152:463–469<br />

Bischof K, Kräbs G, Wiencke C, Hanelt D (2002) Solar ultraviolet<br />

radiation affects the activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase<br />

and the composition of photosynthetic and<br />

xanthophylls cycle pigments <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tertidal green alga Ulva<br />

lactuca L. Planta 215:502–509<br />

Blunt JW, Copp BR, Munro MHG, Northcote PT, Pr<strong>in</strong>sep MR (2005)<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e natural products. Nat Prod Rep 22:15–61<br />

Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C (1995) Use of a free<br />

radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm-Wiss<br />

U-Technol 28:25–30<br />

Cavas L, Yurdakoc K (2005) A comparative study: assessment of the<br />

antioxidant system <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vasive green alga Caulerpa racemosa<br />

and some macrophytes from the Mediterranean. J Exp Mar Biol<br />

Ecol 321:35–41<br />

Choo KS, Snoeijs P, Pedersen M (2004) Oxidative stress tolerance <strong>in</strong><br />

the filamentous green algae Cladophora glomerata and Enteromorpha<br />

ahlneriana. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 298:111–123<br />

Connan S, Delisle F, Deslandes E, Ar Gall E (2006) Intra-thallus<br />

phlorotann<strong>in</strong> content and antioxidant activity <strong>in</strong> Phaeophyceae of<br />

temperate waters. Bot Mar 49:34–46<br />

Davyt D, Entz W, Fernandez R, Mariezcurrena R, Mombru AW,<br />

Saldaña J, Dom<strong>in</strong>guez L, Coll J, Manta E (1998) A new <strong>in</strong>dole<br />

derivative from the red alga Chondria atropurpurea. Isolation,<br />

Structure determ<strong>in</strong>ation, and anthelm<strong>in</strong>tic activity. J Nat Prod<br />

61:1560–1563<br />

Duran R, Zubia E, Ortega MJ, Salva J (1997) New diterpenoids from<br />

the alga Dictyota dichotoma. Tetrahedron 53:8675–8688<br />

Fallarero A, Loikkanen JJ, Mansito PT, Castañeda O, Vidal A (2003)<br />

Effects of aqueous extracts of Halimeda <strong>in</strong>crassata (Ellis)<br />

Lamouroux and Bryothamnion triquetrum (S.G. Gmel<strong>in</strong>) Howe<br />

on hydrogen peroxide and methyl mercury-<strong>in</strong>duced oxidative<br />

stress <strong>in</strong> GT1-7 mouse hypothalamic immortalized cells. Phytomedic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

10:39–47<br />

Fenical W, Paul VJ (1984) Antimicrobial and cytotoxic terpenoids<br />

from <strong>tropical</strong> green algae of the family Udoteaceae. Hydrobiologia<br />

116/117:135–140<br />

Frankel EN, Meyer AS (2000) The problems of us<strong>in</strong>g one-dimensional<br />

methods to evaluate multifunctional food and biological<br />

antioxidants. J Sci Food Agric 80:1925–1941<br />

Fujimoto K (1990) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> activity of algal extracts. In: Akatsuka<br />

I (ed) Introduction to applied phycology. SPB Academic<br />

Publish<strong>in</strong>g, The Hague, pp 199–208<br />

Hay ME, Duffy JE, Paul VJ, Renaud PE, Fenical W (1990) Specialist<br />

herbivores reduce their susceptibility to predation by feed<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

the chemically defended seaweed Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis.<br />

Limnol Oceanogr 35:1734–1743<br />

Heo SJ, Park EJ, Lee KW, Jeon YJ (2005) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> <strong>activities</strong> of<br />

enzymatic extracts from brown seaweeds. Biores Technol<br />

96:1613–1623<br />

Huang HL, Wang BG (2004) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> capacity and lipophilic<br />

content of seaweeds collected from the Q<strong>in</strong>gdao coastl<strong>in</strong>e. J Agric<br />

Food Chem 52:4993–4997<br />

Huang D, Ou B, Prior L (2005) The chemistry beh<strong>in</strong>d antioxidant<br />

capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem 53:1841–1856<br />

Karawita R, Siriwardhana N, Lee KW, Heo MS, Yeo IK, Lee YD,<br />

Jeon YJ (2005) Reactive oxygen species scaveng<strong>in</strong>g, metal<br />

chelation, reduc<strong>in</strong>g power and lipid peroxidation <strong>in</strong>hibition

458 J Appl Phycol (2007) 19:449–458<br />

properties of different solvent fractions from Hizikia fusiformis.<br />

Food Res Technol 220:363–371<br />

Kim SJ, Woo S, Yun H, Yum S, Choi E, Do JR, Jo JH, Kim D, Lee S,<br />

Lee TK (2005) Total phenolic contents and biological <strong>activities</strong> of<br />

Korean seaweed extracts. Food Sci Biotechnol 14:798–802<br />

Kohen R, Nyska A (2002) Oxidation of biological systems: oxidative<br />

stress phenomena, antioxidants, redox reactions, and method for<br />

their quantification. Toxicol Pathol 30:620–650<br />

Kubanek J, Jensen PR, Keifer PA, Sullards MC, Coll<strong>in</strong>s DO, Fenical<br />

W (2003) Seaweed resistance to microbial attack: a targeted<br />

chemical defense aga<strong>in</strong>st mar<strong>in</strong>e fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA<br />

100(12):6916–6921<br />

Kuda T, Tsunekawa M, Hishi T, Araki Y (2005) <strong>Antioxidant</strong><br />

properties of dried ‘kayamo-nori’, a brown alga Scytosiphon<br />

lomentaria (Scytosiphonales, Phaeophyceae). Food Chem<br />

89:617–622<br />

Le Tutour B, Benslimane F, Gouleau MP, Gouygou JP, Saadan B,<br />

Quemeneur F (1998) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> and pro-oxidant <strong>activities</strong> of the<br />

brown algae, Lam<strong>in</strong>aria digitata, Himanthalia elongata, Fucus<br />

vesiculosus, Fucus serratus and Ascophyllum nodosum. J Appl<br />

Phycol 10:121–129<br />

Lim SN, Cheung PCK, Ooi VEC, Ang PO (2002) Evaluation of<br />

antioxidative activity of extracts from a brown seaweed,<br />

Sargassum siliquastrum. J Agric Food Chem 50:3862–3866<br />

Matsukawa R, Dub<strong>in</strong>sky Z, Kishimoto E, Masaki K, Masuda Y,<br />

Takeuchi T, Chihara M, Yamamoto Y, Niki E, Karube I (1997) A<br />

comparison of screen<strong>in</strong>g methods for antioxidant activity <strong>in</strong><br />

seaweeds. J Appl Phycol 9:29–35<br />

Mori J, Matsunaga T, Takahashi S, Hasegawa C, Saito H (2003)<br />

Inhibitory activity on lipid peroxidation of extracts from mar<strong>in</strong>e<br />

brown alga. Phytother Res 17:549–551<br />

Nakamura T, Nagayama K, Uchida K, Tanaka R (1996) <strong>Antioxidant</strong><br />

activity of phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s isolated from the brown alga Eisenia<br />

bicyclis. Fish Sci 62:923–926<br />

Oyaizu M (1986) Studies on products of brown<strong>in</strong>g reaction prepared<br />

fromglucoseam<strong>in</strong>e. Jpn J Nutr 44:307–314<br />

Park PJ, Heo SJ, Park EJ, Kim SK, Byun HG, Jeon BT, Jeon YJ<br />

(2005) Reactive oxygen effect of enzymatic extracts from<br />

Sargassum thunbergii. J Agric Food Chem 53:6666–6672<br />

Pavia H, Cerv<strong>in</strong> G, L<strong>in</strong>dgren A, Åberg P (1997) Effects of UV-B<br />

radiation and simulated herbivory on phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the brown<br />

alga Ascophyllum nodosum. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 157:139–146<br />

Ragan MA, Glombitza KW (1986) Phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s, brown algal<br />

polyphenols. In: Round FE, Chapman DJ (eds) Progress <strong>in</strong><br />

phycological research. Biopress, Bristol, pp 129–241<br />

Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G (1997) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> properties<br />

of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci 2:152–158<br />

Robak J, Gryglewski RJ (1988) Flavonoids are scavengers of<br />

superoxide anions. Biochem Pharmacol 37:837–841<br />

Rupérez P, Ahrazem O, Leal JA (2002) Potential antioxidant capacity<br />

of sulphated polysaccharides from the edible mar<strong>in</strong>e brown<br />

seaweed Fucus vesiculosus. J Agric Food Chem 50:840–845<br />

Safer AM, al-Nughamish AJ (1999) Hepatotoxicity <strong>in</strong>duced by the antioxidant<br />

food additive, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), <strong>in</strong> rats: an<br />

electron microscopical study. Histol Histopathol 14:391–406<br />

Sanchez-Moreno C, Larrauri JA, Saura-Calixto F (1999) Free radical<br />

scaveng<strong>in</strong>g capacity and <strong>in</strong>hibition of lipid oxidation of w<strong>in</strong>es,<br />

grape juices and related polyphenolic constituents. Food Res Int<br />

32:407–412<br />

Santoso J, Yoshie-Stark Y, Suzuki T (2004) Anti-oxidant activity of<br />

methanol extracts from Indonesian seaweeds <strong>in</strong> an oil emulsion<br />

model. Fish Sci 70:183–188<br />

Senevirathne M, Kim SK, Siriwardhana N, Ha JH, Lee KW, Jeon YJ<br />

(2006) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> potential of Ecklonia cava on reactive<br />

oxygen species scaveng<strong>in</strong>g, metal chelat<strong>in</strong>g, reduc<strong>in</strong>g power<br />

and lipid peroxidation <strong>in</strong>hibition. Food Sci Tech Int 12:27–38<br />

Siriwardhana N, Lee KW, Kim SH, Ha JH, Jeon YJ (2003)<br />

<strong>Antioxidant</strong> activity of Hizikia fusiformis on reactive oxygen<br />

species scaveng<strong>in</strong>g and lipid peroxidation <strong>in</strong>hibition. Food Sci<br />

Tech Int 9:339–346<br />

Sun HH, Paul VJ, Fenical W (1983) Avra<strong>in</strong>villeol, a brom<strong>in</strong>ated diphenylmethane<br />

derivative with feed<strong>in</strong>g deterrent properties from the <strong>tropical</strong><br />

green alga Avra<strong>in</strong>villea longicaulis. Phytochemistry 22:743–745<br />

Takamatsu S, Hodges TW, Rajbhandari I, Gerwick WH, Hamann MT,<br />

Nagle DG (2003) Mar<strong>in</strong>e natural products as novel antioxidant<br />

prototypes. J Nat Prod 66:605–608<br />

Targett NM, Boettcher AA, Targett TE, Vrolijk NH (1995) Tropical mar<strong>in</strong>e<br />

herbivore assimilation of phenolic-rich plants. Oecologia 103:170–179<br />

Wei Y, Li Z, Hu Y, Xu Z (2003) Inhibition of mouse liver lipid<br />

peroxidation by high molecular weight phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s from<br />

Sargassum kjellmanianum. J Appl Phycol 15:507–511<br />

Wynne MJ (2005) A checklist of benthic mar<strong>in</strong>e algae of the <strong>tropical</strong><br />

andsub<strong>tropical</strong> western Atlantic: second revision. Nova Hewigia<br />

Beih 129:1–152<br />

Yan XJ, Li XC, Zhou CX, Fan X (1996) Prevention of fish oil<br />

rancidity by phlorotann<strong>in</strong>s from Sargassum kjellmanianum. JAppl<br />

Phycol 8:201–203<br />

Yan XJ, Nagata T, Fan X (1998) Antioxidative <strong>activities</strong> <strong>in</strong> some<br />

seaweeds. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 52:253–262<br />

Yen GC, Chen HY (1995) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> activity of various tea<br />

extracts <strong>in</strong> relation to their antimutagenicity. J Agric Food<br />

Chem 43:27–32<br />

Yuan YV, Bone DE, Carr<strong>in</strong>gton MF (2005) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> activity of<br />

dulse (Palmaria palmata) extract evaluated <strong>in</strong> vitro. Food Chem<br />

91:485–494<br />

Zhang P, Omaye ST (2001) <strong>Antioxidant</strong> and prooxidant roles for βcarotene,<br />

α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid <strong>in</strong> human lung cells.<br />

Toxicol In Vitro 15:13–24