Issue 27 - Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art

Issue 27 - Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art

Issue 27 - Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TRANSLATION SECTION<br />

TRY COAST TO COAST<br />

t VOICES IN FICTION<br />

RVIEW WITH LISA SHEA<br />

!ATORS ON THEIR CRAFT<br />

WINTER 1996-97<br />

I<br />

«... I<br />

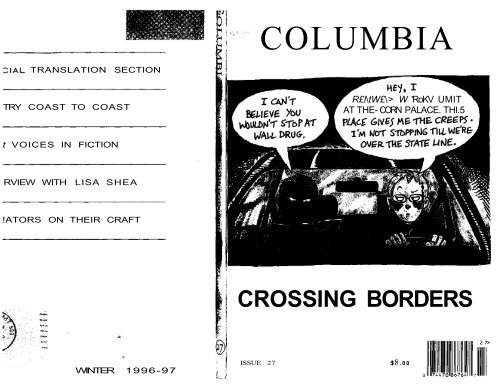

COLUMBIA<br />

R£l\tW£\> W 'RoKV UMIT<br />

AT THE- CORN PALACE. THl.5<br />

CROSSING BORDERS<br />

ISSUE <strong>27</strong> .00<br />

7>

COLUMBIA<br />

A <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Literature</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Art</strong>

Editor-in-Chief<br />

LORI SODBRLIND<br />

Executive Editor<br />

JENNIFER LUCAS<br />

Poetry Editors<br />

JENNIFER FRANKLIN<br />

ELIZABETH STEIN<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Directors<br />

REBECCA D'ALISE<br />

AURORA WEST<br />

Graphic Design<br />

BRYANT PALMER<br />

Managing Editor<br />

GREGORY COWLES<br />

Prose Editor<br />

KEN FOSTER<br />

Asst. Prose Editor<br />

ELIZABETH HICKEY<br />

Circulation Manager<br />

KEVIN ROTH<br />

Editorial Board<br />

GREGORY DONOVAN, STEVE GLAZER, MARTHA GUILD, MYRONN HARDY,<br />

DAVID SEMANKI, SAM SHORES, AMY SILNA, TRACY SMITH, AND RAEVUKOVICH.<br />

Editor's note: This issue <strong>of</strong> COLUMBIA: A JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND ART<br />

presents the winners <strong>of</strong> our annual Winter Competition in poetry <strong>and</strong> prose. The<br />

selection was made from an unprecedented volume <strong>of</strong> highly competitive sub-<br />

missions. The work <strong>of</strong> prose winner Jason Brown <strong>and</strong> poetry winner Michelle<br />

Mitchell-Foust appears in a special section. Poetry judge Linda Gregg's most recent<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> poems, published in 1994 by Gray Wolf Press, is called Chosen By the<br />

Lion. Prose judge A.M. Homes's latest novel, The End <strong>of</strong> Alice, was published by<br />

Charles Scribner's Sons.<br />

COLUMBIA: A JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND ART is a not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it literary journal<br />

publishing fiction, poetry, <strong>and</strong> nonfiction by new <strong>and</strong> established writers. It is edited<br />

<strong>and</strong> produced semiannually by the students <strong>of</strong> the Graduate Writing Division <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Columbia</strong> University School <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Art</strong>s <strong>and</strong> published at 404 Dodge Hall, <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

University, New York, NY, 100<strong>27</strong>. Annual subscriptions are available at $15.00.<br />

Unsolicited manuscripts must be accompanied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope.<br />

1 1996 COLUMBIA: A JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND ART<br />

Don't forget to drive with your high beams on.<br />

—JAN MEISSNER

The Editors would like to thank those who made this issue possible.<br />

For Financial Support:<br />

JOHN L. BLAND<br />

JACKSON BRYER<br />

MORTIMER LEVITT<br />

ELIZABETH OSBORNE<br />

NICK SCHAFFZIN<br />

SIRI VON REIS<br />

JOANNE WOODWARD NEWMAN<br />

For Advisement <strong>and</strong> Creative Support: ALICE QUINN<br />

For Benefit Readings: MARY GAITSKILL AND DAVID LEHMAN<br />

For Design Assistance: JOHN EMERSON<br />

For Fundraising: MIKE MCGREGOR AND SOPHIE HOPKINS<br />

Front cover courtesy <strong>of</strong> ALISON BECHDEL, from "DYKES TO WATCH OUT FOR."<br />

Cartoon by EDWARD KOREN reprinted with permission from THE NEW YORKER.<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Fiction<br />

MICHAEL S. MANLEY<br />

JAN MEISSNER<br />

SHEILA KOHLER<br />

ELIZABETH GRAVER<br />

JOSH HARMON<br />

SPECIAL SECTION<br />

Translation<br />

LlLIANA URSU<br />

KOBO ABE<br />

GWYNETH LEWIS<br />

Poetry FROM THE EAST<br />

ELIZABETH MACKLIN<br />

A History <strong>of</strong> Broken Laws 8<br />

Placedo Junction 15<br />

On the Money 25<br />

A Place Not There 141<br />

Saved From the World 150<br />

Ancient <strong>and</strong> Beautiful as the Mist<br />

Diana's Shadow<br />

Evening After Evening<br />

Blues<br />

From the Angel's Window<br />

Unforgetting<br />

Spring Circumstance<br />

Way <strong>of</strong> the Stars<br />

The Key to Mystery<br />

Number IX<br />

Heirophany<br />

Comic Tunnel, Dialogue <strong>of</strong> Body <strong>and</strong> Soul<br />

H<strong>and</strong><br />

Whose coat is that jacket?<br />

Whose hat is that cap?<br />

The Secret Note You Were<br />

39<br />

40<br />

40<br />

4i<br />

42<br />

43<br />

43<br />

44<br />

46<br />

47<br />

48<br />

49<br />

50<br />

58<br />

H<strong>and</strong>ed by Lorca 70

ELIZABETH MACKLIN<br />

SAMN STOCKWELL<br />

DAVID LEHMAN<br />

LESLEA NEWMAN<br />

TERESE SVOBODA<br />

WILLIAM LOGAN<br />

JUDITH BAUMEL<br />

CHARLES NORTH<br />

SUSAN WHEELER<br />

JEAN MONAHAN<br />

MARIE HOWE<br />

LAURIE SHECK<br />

Poetry FROM THE WEST<br />

LINDA BIERDS<br />

KAY RYAN<br />

JAMES REISS<br />

NANCE VAN WINCKLE<br />

KIM ADDONIZIO<br />

DANIEL TOBIN<br />

NIN ANDREWS<br />

SCOTT C. CAIRNS<br />

BETH GYLYS<br />

NATALIE KUSZ<br />

The Sadness <strong>of</strong> Not Knowing<br />

Perihelion<br />

When a Woman Loves a Man<br />

The Return <strong>of</strong> Buddy<br />

Still Life With Buddy<br />

At the Castle<br />

Thunderstorm<br />

Slugs<br />

Hot<br />

As Moonlight Becomes You<br />

Oldest Psalter<br />

Sleeping Sister<br />

The Concert<br />

Late Morning<br />

The First Gate<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the Last Days<br />

White Light<br />

Black Night<br />

The Harbor Boats<br />

The Breaking-Aways<br />

Shawl: Dorothy Wordsworth at Eighty<br />

Weakness <strong>and</strong> Doubt<br />

Failure<br />

Drops in the Bucket<br />

Lowl<strong>and</strong> Level<br />

Cutting Lentils<br />

Prayer<br />

At the Egyptian Exhibit<br />

How You Lost Your Red Hat<br />

Yahweh's Image<br />

How I Was<br />

After Bedtime<br />

7 1<br />

7 2<br />

73<br />

76<br />

77<br />

78<br />

80<br />

81<br />

82<br />

83<br />

84<br />

85<br />

86<br />

88<br />

89<br />

90<br />

9i<br />

93<br />

95<br />

106<br />

108<br />

no<br />

in<br />

112<br />

"3<br />

114<br />

"5<br />

116<br />

117<br />

118<br />

119<br />

120<br />

NATALIE KUSZ Letter to David, My Father's Best Friend 121<br />

Essay<br />

TOM PERROTTA Bumping Into Klaus:<br />

A Cold War Encounter 122<br />

<strong>Art</strong><br />

an interview with curators<br />

BRONWYN KEENAN <strong>and</strong> MEG LINTON<br />

Comics <strong>and</strong> Cartoons<br />

LESLIE STERNBERGH<br />

JAMES ROMBERGER, MARGUERITE VAN COOK<br />

ALISON BECHDEL<br />

EDWARD KOREN<br />

BRUCE ERIC KAPLAN<br />

Interview<br />

with novelist LISA SHEA <strong>and</strong> screenwriter JAMES BOSLEY 173<br />

Winter Competition<br />

MICHELLE MITCHELL-FOUST<br />

JASON BROWN<br />

97<br />

164<br />

166<br />

168<br />

170<br />

172<br />

Five Songs for a Psalmist 185<br />

Halloween 189

MICHAEL S. MANLEY<br />

A History <strong>of</strong> Broken Laws<br />

Speeding<br />

THE FIRST DAY OF SUMMER, the three <strong>of</strong> us decide to drive up<br />

to Chicago in Johnson's car. Johnson is hung over <strong>and</strong> refuses to<br />

drive. He sits in the front seat with his eyes shut tight. MJ <strong>and</strong> I<br />

put the top down, she gets in behind Johnson, <strong>and</strong> we're gone.<br />

When we hit the Interstate, I keep the car in the left lane <strong>and</strong> pass<br />

everything on the road. A trucker honks at MJ, her long, bare legs<br />

propped up in the back seat. Johnson holds the sides <strong>of</strong> his head<br />

<strong>and</strong> opens his eyes. "I'm giving up drinking," he says. "And I'm<br />

going to take up jogging." I laugh at him. "No, really," he says. "I<br />

feel miserable." MJ leans forward <strong>and</strong> coos "Poor baby," I think.<br />

Johnson <strong>and</strong> I have been yelling over the wind, <strong>and</strong> whatever she<br />

says she says directly into his ear. She reaches over the seat <strong>and</strong><br />

begins to rub his temples. He lays his head back. I stomp down<br />

on the accelerator <strong>and</strong> MJ is thrown back, her black hair flowing<br />

over the seat like a Jolly Roger flag. We rocket past RV's, semis <strong>and</strong><br />

a State Police station, punch-drunk from the sun <strong>and</strong> wind,<br />

howling.<br />

Theft<br />

Johnson works as an orderly at St. Joe's. MJ is a maid at the<br />

TraveLodge. I don't have a job, really, though my half <strong>of</strong> the six<br />

hundred a month Johnson <strong>and</strong> I pay for rent does come out <strong>of</strong><br />

hard work. First, I invested in- a heavy-duty bolt cutter.<br />

At night, when MJ <strong>and</strong> I go for walks around campus, she tells<br />

me about her brother who plays AA baseball or her Scientologist<br />

aunt who's living in a car, <strong>and</strong> I take notes. Her birthday is in<br />

September. She does not like my bright yellow tee-shirt. She<br />

thinks Johnson is a little boy, easily h<strong>and</strong>led. "You're the best<br />

listener I've ever met, Parker." I shrug. "No, really. Most guys<br />

never just let you talk." She has been high twice in her life.<br />

Drunk twice. The next time I go shopping for clothes, she wants<br />

to go with me.<br />

Bikes get ab<strong>and</strong>oned. They get forgotten. MJ <strong>and</strong> I have a<br />

running joke about which ones look good to steal. In the early<br />

morning, I go back out. My bolt cutter cuts chains <strong>and</strong> cables like<br />

paper. I am careful: one bike per week, <strong>and</strong> only machines I can<br />

ride away on. The guy who sells shrimp out <strong>of</strong> a refrigerated truck<br />

in parking lots around town gives me fifteen dollars a bike. He<br />

tucks them behind bags <strong>of</strong> seafood <strong>and</strong> they're never seen again.<br />

"My brother's thinking <strong>of</strong> leaving the game. It's not at all<br />

what he thought it would be," MJ tells me. "One night they got<br />

paid out <strong>of</strong> a van in the parking lot. Half the team got checks <strong>and</strong><br />

the rest got rolled coins <strong>and</strong> singles from the concessionaires' trays.<br />

And I guess women with baseball player fetishes are pretty much<br />

mythical. Hey, how about that yellow one over there? It's been<br />

sitting there a couple <strong>of</strong> days." I point. That one? MJ grabs my<br />

wrist, lifts my arm up to the streetlight. "Open your fist. My God,<br />

Parker, you have perfect h<strong>and</strong>s. I'm not kidding. They're positively<br />

statuesque. I want to draw these h<strong>and</strong>s sometime." Thank you, I<br />

say. Will this be a nude session, or should I wear gloves? "Just don't<br />

scar them up."<br />

I turn the cash into bulk computer disks <strong>and</strong> copy pirated<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware onto them with a disk duplicator that runs all night in my<br />

bedroom. I print out a few hundred labels, give the package to<br />

Amol, who ships them to his brothers in Saudi Arabia. Amol<br />

cracks a new program, gives it to me with my stack <strong>of</strong> twenties.<br />

MJ tells me how many towels, blankets, Bibles <strong>and</strong> rolls <strong>of</strong><br />

toilet paper disappear from the TraveLodge. Johnson tries to top

IO<br />

her with broken locks on pill cabinets <strong>and</strong> a vanished hospital bed.<br />

I tell them to trust no one.<br />

Sl<strong>and</strong>er<br />

I leave town for three days, <strong>and</strong> when I come back there are<br />

two bottles <strong>of</strong> MJ's insulin in the refrigerator. Johnson comes in<br />

from his afternoon jog. "Yeah," he says. "MJ's been staying here<br />

the last couple nights." He raises his eyebrows. You bastard, I say<br />

to him, though I can't keep the perverse smile <strong>of</strong>f my face.<br />

Johnson spreads himself face down on our couch. "You would not<br />

believe the shit I've learned about her, Parker," he says into the<br />

cushions. He rolls over. His eyes hold an expression <strong>of</strong> exhausted<br />

wonder. "She likes to be tied up, man." Yeah, sure. "I'm not<br />

kidding. And get this: she likes doing it outside, too. We had this<br />

totally weird conversation at dinner last night." It's bullshit, I tell<br />

him. She's just trying to get a rise out <strong>of</strong> him. She likes to tell<br />

stories to do that. Johnson sits up <strong>and</strong> wipes the sweat <strong>of</strong>f his face<br />

with his shirt. "Man, I have confirmed the tied up part."<br />

When MJ arrives later, I excuse myself <strong>and</strong> go to my room to<br />

do my work. All night, whenever I need to go to the kitchen or<br />

bathroom, I tiptoe down the hall past Johnson's room. Most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

noise I know is in my head, <strong>and</strong> if I concentrate, if I'm quiet<br />

enough, I won't be able to hear a thing.<br />

Voyeurism<br />

I walk into my bedroom one night <strong>and</strong> before I turn on the<br />

lights I see a naked woman in a window across the street. It is<br />

eleven o'clock, <strong>and</strong> I figure she's getting ready for bed. She walks<br />

back <strong>and</strong> forth in front <strong>of</strong> the window for several minutes, her<br />

breasts <strong>and</strong> bare shoulders perfectly visible. She has a fan running<br />

in the window <strong>and</strong> I realize she must think that because she<br />

cannot see through it from her side, no one can see through it<br />

from the other side either. I focus on my own window, trying to<br />

figure out why it would work the way it does <strong>and</strong> not the way she<br />

expects, <strong>and</strong> by the time I think to look up again, she's turned out<br />

the lights. For the next few nights at eleven o'clock, as Johnson<br />

<strong>and</strong> MJ settle in next to each other on the couch to watch a movie<br />

on TV, I retire to my room <strong>and</strong> watch the woman across the street.<br />

One evening I watch her playwith a ferret, nuzzling its long, furry<br />

body between her breasts, lifting it up to her face to talk to it. I<br />

believe I have seen everything. A few nights later I see her <strong>and</strong><br />

another woman hold each other for several minutes before the<br />

lights go out. I think for a moment I will tell Johnson about this,<br />

but then I remember his claims about MJ, <strong>and</strong> I decide to keep this<br />

to myself. One night when MJ <strong>and</strong> Johnson are over at her place,<br />

a storm blows up. At eleven o'clock the woman across the street<br />

is not home. Her window is dark. There is lightning, <strong>and</strong> for a<br />

moment I see my own reflection in my window: short, dark,<br />

slightly overweight. Johnson is tall <strong>and</strong> athletic <strong>and</strong> looks good<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ing next to MJ. The thunder rolls <strong>and</strong> the disk duplicator<br />

chatters in the dark behind me.<br />

V<strong>and</strong>alism<br />

Two blocks away they're tearing down a row <strong>of</strong> houses. MJ<br />

<strong>and</strong> I watched them rip away chunks <strong>of</strong> building with a huge, steel<br />

claw on the end <strong>of</strong> a digging machine. Walls tore <strong>and</strong> bricks<br />

crumbled, all <strong>of</strong> it sounding like a billion str<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> dried spaghetti<br />

breaking. They sprayed down the piles <strong>of</strong> debris with a fire hose.<br />

They left two small brick houses st<strong>and</strong>ing, one <strong>of</strong> them with a<br />

dozen leaded-glass windows. Salvageable. MJ thinks she can make<br />

end tables out <strong>of</strong> them. Several times during our walk she stops<br />

<strong>and</strong> models with her arms the complex arrangement <strong>of</strong> mannequin<br />

pieces she'll need for the table legs.<br />

At two in the morning I climb over the orange plastic fence<br />

surrounding the demolition <strong>and</strong> jog across the mud <strong>and</strong> shattered<br />

bricks to the shadows between the remaining houses. One window<br />

is ajar, <strong>and</strong> with just a little prying with a crowbar, the wood frame<br />

creaks away. I catch the heavy glass pane in one h<strong>and</strong>, somehow<br />

balance it as I dodge the falling wood, <strong>and</strong> set the window in the<br />

mud. I catch my breath, listen for cars. I put the window outside<br />

the orange fence, lean it against a trash can, then head back for<br />

another.<br />

None <strong>of</strong> the other windows will swing open. I see then that<br />

one corner <strong>of</strong> the house has already been knocked once with the

12<br />

giant claw <strong>and</strong> the walls have shifted, jamming the windows tight.<br />

The window I got isn't big enough to make a large table, <strong>and</strong> MJ<br />

won't want to make just one end table. She already knows where<br />

they'll go in her apartment. I kick the brick chips at my feet, cuss,<br />

then swing the crowbar into the row <strong>of</strong>windows. Glass flies <strong>and</strong><br />

lead seams bend <strong>and</strong> break. If we can't have them, no one can. I<br />

circle the house, giving each window five sharp bashes with the<br />

crowbar. My skin is hot. My h<strong>and</strong>s tingle from the impact. I bark<br />

Shit! Fucker! Shit! with each swing, then run to the other house<br />

<strong>and</strong> begin breaking its windows, too.<br />

I am st<strong>and</strong>ing on the front porch when I see the police car<br />

coming, a spotlight sweeping over the demolished side <strong>of</strong> the<br />

street. I jump <strong>of</strong>f <strong>and</strong> run behind the first house. The spotlight<br />

flashes on my legs. I dive over the thick trunk <strong>of</strong> tree they've torn<br />

down, l<strong>and</strong> in a pile <strong>of</strong> branches. My h<strong>and</strong> scrapes against the<br />

trunk <strong>and</strong> I feel warm blood well up on my knuckles. The crowbar<br />

jabs my hip. I do not breathe, do not flinch. An ant crawls across<br />

my face. I listen to the blood pound in my ears, watch the clouds<br />

pass overhead, lit up by the city lights. I wait for the cops to find<br />

me stupidly frozen behind this tree trunk, but they never come. I<br />

count to three hundred, then poke my head up. I'm safe. I climb<br />

back over the fence, find the windowpane <strong>and</strong> head toward home.<br />

In an alleyway I stop under a lightpole <strong>and</strong> look the window<br />

over. It has been spray-painted almost solid red. One glass square is<br />

missing, two others are cracked. It's worthless. I tuck the window<br />

under my arm like a large book, turn left instead <strong>of</strong> right at the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> the alley. I walk to a nearby parking garage, carry the window<br />

to the top level, st<strong>and</strong> at the edge <strong>and</strong> hurl the thing into the street.<br />

It tumbles for two seconds, spinning slowly, like a giant nine <strong>of</strong><br />

diamonds flicked into the air, then l<strong>and</strong>s flat on the center stripe.<br />

A belly flop. A metallic clap. Glass scatters across both lanes. I think<br />

what torture it would be to walk through it barefoot. It would<br />

sting worse than my bleeding h<strong>and</strong>. The frame is a twisted thing.<br />

No one sees this but me. I do not go home until almost sunrise.<br />

Excessive Noise<br />

MJ slams the door to Johnson's room, storms down the hall,<br />

slams our front door as she leaves. They have been arguing for an<br />

hour. She wants to go with him to his brother's wedding. He<br />

wants to go alone. I know why: one <strong>of</strong> the bridesmaids is a highschool<br />

girlfriend he still sees when he visits his parents. I wait<br />

fifteen minutes. Johnson doesn't leave his room. I go outside <strong>and</strong><br />

walk down the block to the park bench where MJ is sitting. I sit<br />

down next to her. Trouble in paradise? I say. "He can be such an<br />

asshole," MJ says. "He says he's 'not ready' for me to meet his<br />

parents." She has not been crying. I love her for that. I can smell<br />

her sweat. I want to put my h<strong>and</strong>s on her face. You ought to live<br />

with him, I say. You think he's a jerk about this, you ought to go<br />

grocery shopping with him. He likes crunchy peanut butter, for<br />

Christ's sake. MJ laughs. She leans back. "You know, all he <strong>and</strong> I<br />

do is watch movies, eat out <strong>and</strong> fuck." She st<strong>and</strong>s up <strong>and</strong> brushes<br />

the seat <strong>of</strong> her pants. "I'm going back in. Coming?" I shake my<br />

head no <strong>and</strong> watch her walk back up the block. I sit <strong>and</strong> watch<br />

traffic go by, the sky go orange with sunset, <strong>and</strong> wonder what role<br />

it is that I have been assigned. I wonder if my face has started to<br />

lose its features, or if I am fading into invisibility. I head back to<br />

the apartment, climb the stairs to the third floor. At the door, I<br />

hear sounds that have become as familiar to me as the purr <strong>of</strong> my<br />

computer. Sounds I hear from down the hall almost every night.<br />

I open the door. A flash <strong>of</strong> Johnson leaning over MJ on the couch,<br />

<strong>of</strong> h<strong>and</strong>s moving under clothing, <strong>and</strong> I slam the door closed again.<br />

Murder<br />

I am driving home after the seafood trucker pays me <strong>and</strong> I<br />

stop at an ab<strong>and</strong>oned feed mill near some railroad tracks. I drive<br />

by it all the time. The building is boarded up <strong>and</strong> surrounded by<br />

weeds as tall as I am. Spray-painted graffiti covers most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

bricks. EVAN + JUDY COUGARS RULE JESUS SAVES I<br />

look through a gap in the boards. Inside, the building is empty,<br />

dusty <strong>and</strong> undisturbed. No one comes here. There are no other<br />

buildings for at least a half-mile. This is how it works: while<br />

Johnson is on his evening jog, I hit him with my car. I know just<br />

the stretch <strong>of</strong> highway. I come at him from the other direction,<br />

cross the center line <strong>and</strong> clip him with the front bumper. The look

o<br />

a:<br />

ID u.<br />

O<br />

>-<br />

IT<br />

0<br />

in<br />

on his face is priceless; it's the look he had when he found the<br />

moldy potato salad in the refrigerator, his tongue sticking out as<br />

he says bleck. I tie him up in the back seat, bring him to this<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>oned building. "Burning Down the House" plays from his<br />

tape player's headphones the entire way over. Thump him on the<br />

head again if the car didn't kill him. Pour lime over his body, nail<br />

the boards back in place. Take the tape player. I will have to<br />

steal a car so mine isn't recognized, but the way the summer is<br />

progressing, that's not a surprise. MJ will be frantic <strong>and</strong> I will have<br />

to console her. I'll have to wait for one <strong>of</strong> the nights when he<br />

doesn't go jogging until after dark. MJ will want to solve his<br />

disappearance herself. Nancy Drew, bondage queen. I leave to go<br />

home <strong>and</strong> feel my plans unraveling as I weave them.<br />

Perjury<br />

The message on our answering machine is from Donna, the<br />

bridesmaid. She's coming to visit, taking Johnson up on his longst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer <strong>of</strong> a place to sleep whenever she wants. The purr<br />

she affects for that part <strong>of</strong> the message makes me want to laugh.<br />

She will arrive tonight, at about midnight. I let the machine erase<br />

the message. When Johnson comes home for lunch, he asks if<br />

there were any calls for him. No, I say. While he is eating, he finally<br />

asks me, "Parker, does it bother you I'm doing MJ? I know you<br />

guys are friends <strong>and</strong> all." I shake my head. No, I'm OK with it.<br />

No big deal.<br />

JAN MEISSNER<br />

Placedo Junction<br />

WHERE WE LIVED, "Where to tonight?" didn't have many answers.<br />

Home was a mud field, an oil camp where derricks were trees <strong>and</strong><br />

the miles between houses meant talk to your own self for someone<br />

to talk to.<br />

Mother said how many days you managed to get through sane<br />

in that heat was a mark <strong>of</strong> how strong you were getting to be. Or<br />

worn down.<br />

Nothing had a shine in Placedo. Nothing but Earl's, that is, a<br />

roadhouse whose neon made nighttime a darkness you needn't be<br />

lonely because <strong>of</strong>.<br />

Earl's unopened was dank <strong>and</strong> boarded <strong>and</strong> shuttered but<br />

Earl's with the lights on was where you wanted to be. If you'd<br />

never been farther than just up the road or done more than get<br />

through a day, then "Earl's" blinking red in a circle <strong>of</strong> bloodcolored<br />

gravel caused your heart to beat faster.<br />

Pulling into Earl's meant Mother checked her lips in the<br />

mirror on the back <strong>of</strong> the visor, said "Look at who's talking," when<br />

Eugene told her it looked as if who she cared how she looked to<br />

was some man other than that sweet-faced husb<strong>and</strong> who'd driven<br />

her there.

0<br />

H uzD<br />

"3<br />

0<br />

Q<br />

16<br />

Mother just laughed. She said slicked-back hair <strong>and</strong> python<br />

boots so high in the heel my father had to stoop when he danced<br />

took the How-do-I-look? prize.<br />

They did like to dance, <strong>and</strong> I liked to watch them on a<br />

Saturday night, Eugene looking bored <strong>and</strong> tight <strong>and</strong> Mother looking<br />

dazed from how she had to wait for signs from Eugene s h<strong>and</strong>s, my<br />

father being a slow smooth dancer with a snakelike style that made<br />

it seem his feet were hardly moving. But they were.<br />

Mother wore slippers that had to be kicked <strong>of</strong>f to dance in,<br />

open-toed, low-vamped red things her younger sister Lona asked<br />

to borrow <strong>and</strong> her older sister Martha called "sin shoes."<br />

There wasn't much sin in Placedo. Martha said a woman was<br />

a fool to be tempted, everyone watching to see if she was, when<br />

she was, <strong>and</strong> by whom.<br />

Earl's made it hard not to be. "That long-backed oil field<br />

worker at the end <strong>of</strong> the bar," Lona said,"the one with a plain gold<br />

b<strong>and</strong> stuffed down in the bottom <strong>of</strong> his pocket <strong>and</strong> 'No place to<br />

go but back home' in his eyes? The one who was lifting his glass<br />

up <strong>and</strong> smiling at you? That oil field worker looked a whole lot<br />

better than a book on a couch <strong>and</strong> a ceiling you knew every<br />

corrugated inch <strong>of</strong>."<br />

Lona said romance was just a h<strong>and</strong>ful <strong>of</strong> dimes, some cowboy<br />

with just enough paycheck to buy you a beer, just enough style to<br />

roll you a smoke <strong>and</strong> light it on the side <strong>of</strong> his thumb, a rodeo rider<br />

in a h<strong>and</strong>-tooled belt that read "Sonny," on his way up to Austin<br />

who wanted to know what a sweet thing like you could be doing<br />

in a bad place like Earl's.<br />

It wasn't really that bad. Smoke <strong>and</strong> drink <strong>and</strong> the perfume <strong>of</strong><br />

women with men they didn't belong with made Earl's <strong>of</strong>flimits to<br />

some <strong>and</strong> a magnet to others. Mother said the women looked<br />

lovely because <strong>of</strong> how wanted they were hoping to be <strong>and</strong> the<br />

men looked better than they usually did.<br />

Martha didn't buy it. She said nights you reached out <strong>and</strong><br />

steadied yourself at the bar, nights Earl helped you into your truck<br />

<strong>and</strong> pointed which direction your home was, added your name to<br />

that pact Earl had signed with the devil when he opened a road-<br />

house. She said Mother <strong>and</strong> Eugene shouldn't take their daughter<br />

to a place where the stories-swere lies <strong>and</strong> the smoke wasn't only<br />

tobacco.<br />

Eugene <strong>and</strong> Mother got angry. Eugene said Earl was a friend<br />

who gave a man credit when he didn't have any money <strong>and</strong> held<br />

out a Zippo for a woman when nobody noticed that she needed<br />

a light. Mother said taking her daughter to Earl's was a damned<br />

sight better than leaving her alone with a dog on a chain for a<br />

friend <strong>and</strong> protection. She said, "Thank God for something at the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> the day, even if all that something happens to be is a roadhouse<br />

called Earl's."<br />

Martha took it back. She had to since all that she had in this<br />

life was her family. Mother said Martha unloved was a genuine<br />

waste but Lona unloved was just one more roughneck with<br />

cellophane flowers <strong>and</strong> a box full <strong>of</strong> c<strong>and</strong>y <strong>and</strong> a grin on his face<br />

delayed by an engine burned out from how fast he'd been driving<br />

there to give her those things.<br />

Long bare legs hiked up on the dash <strong>of</strong> a truck pulled over in<br />

the dark—you could make a bet were Lona's. And somebody's<br />

husb<strong>and</strong> was with her. Or a boy raised to be sinless who wasn't<br />

anymore. No one was not good enough. Mother said if Lona<br />

couldn't love you then nobody could. "All it takes is a match held<br />

out to her Lucky. A Stetson lifted up above a genuine smile."<br />

On a bad day, Lona said women love men <strong>and</strong> men let them.<br />

Good days, close in the evening <strong>and</strong> kind in the morning, a goodbye<br />

kiss she wouldn't be able to say wasn't love was enough.<br />

It had to be enough. Mother said you never got used to no<br />

sound in Placedo, to no one knocking on your door but a stranger,<br />

the driver <strong>of</strong> a car left idling who was looking for some place<br />

you'd never heard <strong>of</strong>, a stranger you'd gladly give a glass <strong>of</strong> iced tea<br />

to <strong>and</strong> directions, if you could, <strong>and</strong> a s<strong>and</strong>wich <strong>and</strong> a chair in the<br />

shade <strong>and</strong> your own life story, if that stranger was willing to listen.<br />

In the place where we lived, small pleasures were worth what<br />

in some other place greater pleasures would have been. Some big<br />

place like Houston. Or Nuevo Laredo.<br />

My father used to go to Nuevo Laredo. But he didn't go by<br />

the time that I knew him. And if he did, he wouldn't take his wife

18<br />

or his daughter. He said north <strong>of</strong> the border was always much<br />

safer than south. Over the border meant you had to watch what<br />

you ate <strong>and</strong> take care where you ate it if a hard rubber tube down<br />

your throat <strong>and</strong> a case <strong>of</strong> the shakes <strong>and</strong> the sweats on a narrow<br />

white cot in the critical ward at the Holy Mary convent clinic<br />

wasn't quite your notion <strong>of</strong> a good time night on the town.<br />

But if ptomaine didn't matter, if sober was something you<br />

weren't able to recall what it felt like to be <strong>and</strong> your taste buds<br />

were fried from the smoke <strong>and</strong> the weed <strong>and</strong> the worms at the<br />

bottom <strong>of</strong> too many bottles <strong>of</strong>Tomo Tequila, then my father<br />

had a long list <strong>of</strong> late-night places he said he'd be pleased to<br />

recommend—<strong>and</strong> you could say that he sent you—dives with a<br />

room overhead you could rent for an hour—for whatever<br />

reason—back street cantinas where the man behind the bar cut<br />

first class anjeo with grain <strong>and</strong> spiced his tamales so a patron never<br />

guessed there was greyhound mixed with the beef.<br />

Eugene said, that dog you laid down the bulk <strong>of</strong> your paycheck<br />

on just a few weeks ago at the dog track, that one-time<br />

first-place runner that had given up sprinting for loping on<br />

arthritic haunches might well be the meat <strong>of</strong> a red-hot tamale you<br />

were peeling the corn husk back on—that is, if you ate in those<br />

places Eugene recommended.<br />

Higher aspirations in Nuevo Laredo were a gold tipped<br />

Havana boated over from Cuba <strong>and</strong> a shot <strong>of</strong> Jalisco mescal from<br />

the wild blue agave to wash down a plate <strong>of</strong> frijoles borrachos.<br />

But you had to have luck with frijoles borrachos. Not much<br />

business made a cantina owner cut costs, made a cook scrape back<br />

in the pot what another man left in his plate, some cowboy with<br />

serious appetite loss <strong>and</strong> loose gray skin <strong>and</strong> a cough he hadn't<br />

been able to kick so that whoever bought his portion <strong>of</strong> chili <strong>and</strong><br />

beans got a little bit more than he paid for. Or more than a little.<br />

Eugene said not even Jesus in fourteen carat on a chain around<br />

your neck, not even the foot <strong>of</strong> a rabbit you'd tied to the b<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

your Stetson made a difference when things stopped going your<br />

way in Nuevo Laredo.<br />

Whether it was dog or it was King Ranch grain-fed beef in<br />

your enchiladas mole depended on whether the run you were on<br />

was a good one or not. S<strong>and</strong>bagged cold in an alley with your<br />

pockets turned out <strong>and</strong> yo-etr belt <strong>and</strong> boots stripped <strong>of</strong>f meant<br />

luck wasn't yours anymore. But the nails <strong>of</strong> a perfumed cantina<br />

dancer sunk into the curve <strong>of</strong> your spine as she whispered,<br />

"Enamorado," meant you had just enough luck left to make it<br />

back over the Cordova Bridge <strong>and</strong> stay on that side <strong>of</strong> the Rio<br />

Gr<strong>and</strong>e del Norte where nothing bad happened.<br />

Eugene said you had to think real hard before crossing that<br />

border again, certified King Ranch steak being bound to be<br />

better than a greyhound tamale you only had a fifty-fifty chance<br />

<strong>of</strong> surviving.<br />

Earl's <strong>of</strong> Placedo was safer, he said, people you'd known all<br />

your life <strong>and</strong> beer that was bottled <strong>and</strong> plates <strong>of</strong> those ribs Earl<br />

swore up <strong>and</strong> down on a bible were cut from the side <strong>of</strong> a top<br />

grade longhorn he guaranteed he knew who the breeder <strong>of</strong> was,<br />

ribs in a sauce that was sweeter or hotter depending on how things<br />

were going with Earl.<br />

Hard times, Earl dumped in Tabasco. Good times, he dumped<br />

in molasses so if you liked it hot, you might find yourself wishing<br />

some small bit <strong>of</strong> trouble would l<strong>and</strong> on his doorstep. Not much.<br />

Just a little, since Earl in a funk that he couldn't pull out <strong>of</strong> was<br />

something you didn't want to see. Not if you'd already seen it.<br />

Not if you'd been around when his wife ran <strong>of</strong>f with his partner<br />

<strong>and</strong> all <strong>of</strong> his Guadeloupe National savings.<br />

Earl in the red, Earl in debt to the Lone Star brewery <strong>and</strong><br />

Southwest Power <strong>and</strong> Light <strong>and</strong> the ranch those prime slabs <strong>of</strong> rib<br />

were trucked down from meant Earl's, as you knew it, was over,<br />

for a time, the juke box strapped to the back <strong>of</strong> a repossess truck<br />

<strong>and</strong> the lights turned <strong>of</strong>f when you got there.<br />

Earl said the only way out <strong>of</strong> a mess like the mess he was in<br />

was through hard work <strong>and</strong> patience <strong>and</strong> acts <strong>of</strong> contrition he<br />

made himself say, Earl being Placedo's only real Catholic, one with<br />

no church to go to since what we had for a church was whatever<br />

preacher on the Gulf Coast Evangelist circuit might set up a tent<br />

in a field <strong>and</strong> stay until cash in the donation basket had piled high<br />

enough to move on.

All the Catholics that Earl ever talked to were crawlers.<br />

Mother explained, when I asked her, that a crawler was a man on<br />

his knees on his way down south to a pilgrimage church that he<br />

had to pass through Placedo to get to, a Mexican mostly, making<br />

his way to a black ash Madonna that was rumored to sew up your<br />

wounds, if you dropped a drop <strong>of</strong> the blood from your knees on<br />

the hem <strong>of</strong> her skirt, a h<strong>and</strong>-embroidered robe that was stiff as a<br />

board from how much blood there was on it.<br />

Earl took a bucket <strong>of</strong> water <strong>and</strong> sprinkled the crawler to cool<br />

him, walked by his side for a bit <strong>of</strong> the way, asking questions if the<br />

crawler spoke English, crossing himself if he didn't.<br />

Mother said that was a sight. Earl Bodel <strong>and</strong> a crawler with a<br />

two-by-four cross tied onto his back. She said it looked frcm a<br />

distance like Earl was out walking his dog so if you'd been driving<br />

that interstate road we were on, <strong>and</strong> you'd come across Earl <strong>and</strong> a<br />

crawler, you probably would have taken your foot <strong>of</strong>f the pedal,<br />

taken your sunglasses <strong>of</strong>f <strong>and</strong> turned your head around to see what<br />

the hell what you'd seen really was.<br />

Earl doing his best to get back on his feet was the roadhouse<br />

locked <strong>and</strong> pads tied onto his knees, not for a crawl but for an all<br />

night burning <strong>of</strong> c<strong>and</strong>les he told us were blessed by a Monterrey<br />

Padre <strong>and</strong> sent through the mails, c<strong>and</strong>les with saints painted on<br />

them, bone-thin Sebastions that were run through with arrows,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a brown-skinned Mary with rhinestone tears glued onto her<br />

cheeks that had streamed one evening, had rolled, Earl swore, in a<br />

copious way, down the pale white beeswax stain <strong>of</strong> her skin, a sign,<br />

according to Earl, that God wanted Earl's back open. Right away.<br />

To make people happy.<br />

Next day, Earl took a loan out <strong>and</strong> opened for business.<br />

Mother said a sign like that must have had a little something<br />

to do with the Tomo Tequila, but Eugene said whatever lifted Earl<br />

Bodel from the dumps was okay by him since the lights turned out<br />

when you pulled up in front meant no place to go <strong>and</strong> no one to<br />

go there with but those with a surname the same as your own.<br />

Nights when Earl's wasn't open, our family had to drive back<br />

home <strong>and</strong> make a party out <strong>of</strong> just who we were, my mother Leda<br />

Marie <strong>and</strong> my father Eugene, me, <strong>and</strong> Aunt Martha <strong>and</strong> Lona.<br />

It wasn't much <strong>of</strong> a party. My father, pitching a ball to<br />

himself in the dark, said a "Brother-in-law argund the place<br />

wouldn't cause any pain—some fellow a fellow could talk to while<br />

Mother was talking with Martha <strong>and</strong> Lona, whispering in a swing<br />

on the porch so a husb<strong>and</strong> felt lonely <strong>and</strong> a daughter had to sit<br />

very close if she wanted to hear all the gossip.<br />

You had to scrounge for your gossip in Placedo Junction.<br />

Small things happened. Mother said awful was better than<br />

nothing at all. Third-h<strong>and</strong> got you through an evening, something<br />

someone in some other town you'd never even been to was said<br />

to have done.<br />

The rest <strong>of</strong> Placedo had Lona to gossip about.<br />

Martha said, "What would they do without Lona?"<br />

Mother said not even half <strong>of</strong> those circulating stories had a<br />

basis in fact.<br />

Lona was Baby to Mother <strong>and</strong> Martha. But Eugene said Lona<br />

wasn't getting any younger.<br />

"Come forty or fifty," he said, "that face, on its way between<br />

lovely <strong>and</strong> gone, won't look quite as good in the flame <strong>of</strong> a Zippo.<br />

Over the hill means out <strong>of</strong> the picture, means no one can see you.<br />

Over the hill means you better find yourself some man to hold<br />

onto, a good man, not one <strong>of</strong> those roughnecks you like to laugh<br />

in the low light <strong>of</strong> Earl's with."<br />

Lona said good was a hard thing to find in Placedo.<br />

Eugene had a damned fine idea where to look, he told her. If<br />

she cared to.<br />

"I'll bet he means Earl's," Mother said. "But behind, not in<br />

front <strong>of</strong> the bar."<br />

Lona just laughed. "Leg to leg on a stool at that bar," she said,<br />

"is a small-time thrill that takes a woman's mind <strong>of</strong>f how lonely<br />

her life would have been without someplace like it. But who'd<br />

•want to live there? Earl's is a roadhouse you go to that you can<br />

come back from. Not stay in. If a woman married Earl, she'd<br />

know every inch <strong>of</strong> Earl's ceiling. Then where would she go to<br />

forget it?"<br />

Eugene said Earl Bodel needed someone to help get his spirits<br />

back up, <strong>and</strong> word had it that a woman he knew named Lona was

in charge <strong>of</strong> the lifted-up-spirits concession in Placedo Texas. At<br />

least among the male population.<br />

Lona kept right on brushing <strong>and</strong> braiding my hair. She told<br />

Eugene that Earl wasn't really her type.<br />

Eugene didn't know there was such a thing, he said, a fellow<br />

who wasn't her type.<br />

My aunt's aim wasn't good <strong>and</strong> she missed Eugene with the<br />

brush when she threw it. But he reached out <strong>and</strong> caught it in the<br />

mitt on his h<strong>and</strong> so that Lona had to chase him down to get it<br />

back, trip him <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> on top <strong>of</strong> his stretched out body <strong>and</strong><br />

pound him, laughing, <strong>and</strong> screaming.<br />

Martha shook her head, She said neighbors, if there'd been<br />

any neighbors to hear us, would have called us heathens for the<br />

sound <strong>of</strong> how raucous we were.<br />

Mother just waited it out. She thought nothing <strong>of</strong> it. She was<br />

used to her sister going after her husb<strong>and</strong>, pinning him down or<br />

backing him up against a wall so that just to get away my father<br />

had to twist Lona's arm behind her back until she begged him for<br />

mercy, until finally, she cried.<br />

That was all that she wanted. Lona had to cross that line now<br />

<strong>and</strong> then between not quite enough <strong>and</strong> a good deal too much,<br />

Mother said. After that she was fine, except for how heavy the<br />

breathing she did was.<br />

Eugene didn't go back to pitching a ball to himself. My father<br />

hooked the heel <strong>of</strong> his boot on the back <strong>of</strong> Mother's chair <strong>and</strong><br />

rested his h<strong>and</strong>s on her shoulders. Mother said, "What is it,<br />

honey?" since Eugene hardly ever came close on a night when the<br />

sisters were talking.<br />

But he didn't say anything. Nobody did. We all just sat in the<br />

dark with the yard lights <strong>of</strong>f, listening to the pumps in the field<br />

until Martha told Lona it was time to go home <strong>and</strong> let the<br />

B<strong>and</strong>eras side <strong>of</strong> the family grab a little shut-eye.<br />

Eugene checked the air in Marthas tires <strong>and</strong> Mother said,<br />

"Lock all the doors. Don't forget to drive with your high beams<br />

on. Watch out for Lona."<br />

There wasn't any danger. Eugene said, "Nothing to fear" was<br />

the alternate side <strong>of</strong> the "Nothing to do" coin.<br />

After the sisters were gone, it was quiet, so a girl in her bed<br />

got to hear her mother <strong>and</strong>-father in a swing on the porch say<br />

things she might not have heard if they'd known their daughter<br />

wasn't sleeping.<br />

Mother told Eugene that Martha had a hard on for Earl.<br />

When Eugene said, "Bull," Mother swore on the head <strong>of</strong> her<br />

daughter. She'd watched it develop, she said, the blush when Earl's<br />

name was brought into the story, how tongue-tied she was when<br />

she saw him. But Earl wasn't looking at Martha since he was too<br />

busy looking at Lona, watching to see whether Lona might want<br />

anything, a dusted <strong>of</strong>f seat at the bar, or a beer, or a light for a link<br />

in the chain <strong>of</strong> her Luckies. Mother said why Earl couldn't see<br />

Martha was a mystery that she couldn't fathom.<br />

Eugene said it wasn't a mystery. All Mother had to do was<br />

take a look at the two <strong>of</strong> her sisters.<br />

That's when Mother said lovely doesn't matter. And ugly<br />

doesn't either. She said, "One arm withered makes the other arm<br />

stronger."<br />

Eugene didn't know about that, he said, but one thing he did<br />

know. And that was that Martha in a union with Earl was a heartstopping<br />

thought. Sun tea. Limeaid. No smoking <strong>and</strong> the neon<br />

sign <strong>and</strong> the lights turned out before nine so that nowhere to go<br />

would be all she wrote in a town where a nicotine fit was diversion<br />

<strong>and</strong> a man had to make something up just to say something<br />

happened.<br />

What he suggested, he said, if Mother wanted life to go on as<br />

she knew it, was just to forget about sisters <strong>and</strong> give her husb<strong>and</strong><br />

that kiss he'd been wanting all night.<br />

But she wouldn't do it. She said she had Eugene, <strong>and</strong> Lona<br />

had cowboys, but Martha needed someone to be with on nights<br />

when a guard dog asleep on the porch <strong>of</strong> a house you passed in<br />

the dark made you feel it was you locked out <strong>and</strong> not the<br />

neighbors locked in.<br />

Martha, growing up beside Leda <strong>and</strong> Lona, was an unfair<br />

thing, Mother said. Boy after long-backed fired-up boy pulled up<br />

to the yard with a rubber in his wallet he was praying was all that<br />

would st<strong>and</strong> between him <strong>and</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Martha's two sisters. Mother

said all Martha got on those nights was a pat on the back <strong>and</strong> a<br />

"How you doing, Martha," but Leda <strong>and</strong> Lona, in the cab <strong>of</strong> a<br />

truck with the engine turned <strong>of</strong>f <strong>and</strong> the s<strong>of</strong>t white light <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Placedo moon up above, got to see what a tattooed snake looked<br />

like that could strike when a boy flexed the muscle in an arm he<br />

had dared them to put their sweet little fingertips on.<br />

Eugene said he never had heard about the boys with the<br />

snakes on their arms <strong>and</strong> why hadn't Mother told him that story.<br />

She said, "Hush, Eugene." She said if he'd help to fix things<br />

up between Martha <strong>and</strong> Earl, she'd give him that kiss he'd been<br />

wanting.<br />

I couldn't hear anymore after that, except the creak <strong>of</strong> the<br />

swing on the porch <strong>and</strong> what sounded like Eugene's boots coming<br />

<strong>of</strong>f, a rustle <strong>and</strong> a whisper that might have been nothing but a<br />

breeze just over from the coast making noise in the branches <strong>of</strong> a<br />

chinaberry tree.<br />

Everything was quiet, <strong>and</strong> dark where we were, so if you'd<br />

been driving that interstate oil field access road, <strong>and</strong> you'd caught<br />

our house in the beam <strong>of</strong> your headlights, you might not have<br />

known we were there. You probably would have kept on driving.<br />

Right past us. Like most people did. North. Up to Houston. Or<br />

south. To Nuevo Laredo.<br />

SHEILA KOHLER<br />

On the Money<br />

THE WIFE SAYS, "I don't want to discuss it."<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "But you said you would. You promised.<br />

You have to."<br />

The wife says, "I told you I don't want to talk about it. It's my<br />

money, after all. I'll do what I think best."<br />

The wife lifts her glass, lets the stewardess fill it with<br />

champagne, helps herself to another salmon canape. The husb<strong>and</strong><br />

refuses the champagne <strong>and</strong> canapes. He says to the wife, "Alcohol<br />

is not good for jet lag."<br />

The wife says, "Oh, for God's sake, just relax <strong>and</strong> enjoy<br />

yourself for once, can't you?"<br />

He shakes his head, says, "You have to honor a promise. We<br />

agreed on the sum, didn't we?"<br />

The wife says, "I don't have to do exactly what we agreed to.<br />

I have thought it over since then. A person can change her mind.<br />

It's just too much. It's a ridiculous amount <strong>of</strong> money. Besides, I<br />

didn't realize those lawyers would take so much <strong>of</strong> it, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

dreadful real estate man, <strong>and</strong> the taxes. I have never given that<br />

much to anyone. Not even my children."<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "Well, give some money to your children. I<br />

think that you should give more to your children. Why don't you?"

The wife says, "Oh, shut up, won't you," pushes her seat back,<br />

draws the grey duvet up <strong>and</strong> over her chest, <strong>and</strong> pulls her mask<br />

down to cage her eyes.<br />

She spots the caretakers walking through the crowd at the<br />

airport to greet them. They seem smaller than she remembers<br />

them. Gianna is wearing a loose cream sweater. Michelino looks<br />

diminutive, like his name, in well-pressed pleated brown pants <strong>and</strong><br />

a pink cotton shirt. They have the elegance <strong>of</strong> people who live<br />

beside the elegant, dress as the elegant do, but who are not,<br />

ultimately, elegant. The wife thinks the caretakers look young, or<br />

anyway younger than she or her husb<strong>and</strong>, but then, she reminds<br />

herself, the caretakers are younger. She remembers them bringing<br />

out their album <strong>and</strong> showing her their wedding photos during a<br />

dinner at their house. They shake h<strong>and</strong>s with her respectfully. The<br />

caretakers inquire about the trip. The husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> wife say how<br />

they are pleased to have arrived. Michelino says, "I was afraid you<br />

would never come back."<br />

"But we promised," the wife says, <strong>and</strong> Michelino lowers his<br />

respectful gaze <strong>and</strong> looks embarrassed.<br />

They all walk outside into the warm s<strong>of</strong>t air. The wife takes<br />

a big breath. There is that familiar smell <strong>of</strong> some sweet herb she<br />

has never been able to identify.<br />

In the car the husb<strong>and</strong> sits in front with Michelino, the wife<br />

in back with Gianna. The caretakers <strong>of</strong>fer lunch, their car, their<br />

home. The wife says no, they prefer the hotel, which is in town,<br />

so that they will not need a car. They are here for such a short stay,<br />

she says, <strong>and</strong> they have business in the town. They must attend to<br />

it immediately, so that they cannot make lunch. They have to go<br />

to the bank, before it closes. Besides, they have eaten so much on<br />

the plane. They will see the caretakers that evening for dinner,<br />

when they have accomplished their business.<br />

There is a respectful silence in the car. The wife looks out the<br />

window. On one side there is the jagged coast line, the dark rocks,<br />

the smooth sea, the glitter blurred by a faint haze, on the other, the<br />

fields <strong>of</strong> wild juniper, the yellow flowers glistening in the gold<br />

autumnal light. Every year she has come back here, first with one<br />

husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> her children, <strong>and</strong> now with this one. She has been surprised<br />

each time to find it more beautiful than she remembered it.<br />

The wife asks the caretakers about the German couple who<br />

bought their villa. Gianna raises her h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> puts the tips <strong>of</strong> her<br />

fingers together like a money bag in the familiar gesture all Italians<br />

use even when talking on the telephone. She frowns <strong>and</strong> says, "I<br />

don't underst<strong>and</strong> why they let us go. First Michelino <strong>and</strong> then me."<br />

"Perhaps they did not want anyone full-time," the wife says.<br />

Gianna says, "It's not as though they lacked for money."<br />

"That's true," the wife says <strong>and</strong> thinks <strong>of</strong> how the Germans<br />

paid in cash.<br />

Gianna says, "They just wanted their own people, I suppose."<br />

The wife sighs <strong>and</strong> shakes her head. Gianna begins to tell the<br />

wife about the changes the Germans have made to the villa, but<br />

the wife lifts a h<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> says, "Don't tell me. I don't want to hear,"<br />

<strong>and</strong> shuts her eyes.<br />

The bank director has very blue eyes, thick black lashes, <strong>and</strong><br />

an intense stare. He smiles at the wife through the glass door. He<br />

has replaced the director she remembers. He opens the door for<br />

her, <strong>and</strong> asks if her husb<strong>and</strong> would like to join them, glancing at<br />

him pacing up <strong>and</strong> down across the green marble floor in the dark<br />

hall. The wife says quickly, "No, no, it's not necessary."<br />

The director says, "I see," <strong>and</strong> ushers the wife into a small,<br />

sound-pro<strong>of</strong> room with orange walls. She sits down. He sits<br />

opposite her behind the big wooden desk. "What can I do for<br />

you?" he asks. She leans forward in her chair <strong>and</strong> says in a low<br />

voice, "I would like half the money in lire <strong>and</strong> the other half in<br />

travellers' cheques."<br />

He nods <strong>and</strong> spreads his fingers. "As you like, Signora." He<br />

makes a call <strong>and</strong> goes out <strong>of</strong> the room for a moment. He comes<br />

back with a pile <strong>of</strong> Italian notes <strong>and</strong> the cheques in a silver plastic<br />

folder. He says, "I thought five hundreds would be easier for you<br />

to sign." She nods her head <strong>and</strong> signs the cheques fast, making her<br />

signature as short as possible. He asks if she would like him to<br />

count the notes. She nods. He starts to count, counting fast in<br />

Italian. She loses count.<br />

<strong>27</strong>

At her request he puts the bills in a brown paper envelope <strong>and</strong><br />

seals it. She puts the envelope <strong>and</strong> the travellers' cheques in a<br />

pocket <strong>of</strong> her h<strong>and</strong>bag.<br />

When she walks out <strong>of</strong> the windowless room, her husb<strong>and</strong><br />

emerges from the shadows. He walks with the quick impatient<br />

steps <strong>of</strong> the doctor who has little time. He, too, always surprises<br />

her when she sees him after even a short absence. She never<br />

remembers how youthful he looks, with the smooth cream skin,<br />

the light freckles she associates with his race, which has always<br />

seemed to her both familiar <strong>and</strong> exotic. Sometimes his skin looks<br />

so smooth she thinks it looks like a mask. He is not tall but slim<br />

with a thick head <strong>of</strong> dark hair, a nose she thinks <strong>of</strong> as aquiline <strong>and</strong><br />

s<strong>of</strong>t, dark, rather close-set eyes. He smiles a crooked smile <strong>and</strong><br />

inquires, "Done?"<br />

"Done," she says, <strong>and</strong> they walk out onto the piazza, arm in<br />

arm. He squeezes her arm <strong>and</strong> says, "Good for you."<br />

The sun does not have the strength <strong>of</strong> summer sun; there is a<br />

s<strong>of</strong>t haze in the air, but the leaves <strong>of</strong> the olive trees are filled with<br />

gold light. A slight breeze nags at the hem <strong>of</strong> her dress. She kisses<br />

the husb<strong>and</strong> on his smooth cheek. She says, "Let's just have a look<br />

at the shops, for a minute, <strong>and</strong> then we'll take a picnic in the<br />

launch to the beach."<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "The shops can wait until later this afternoon.<br />

We ought to check into the hotel now <strong>and</strong> put all this money<br />

away. It's not safe to walk around with so much."<br />

She asks the hotel manager if she might put something in the<br />

safe. He, too, says, "Of course, Signora," <strong>and</strong> ushers her into a small<br />

room with a big blue bowl filled with white lilies. She can smell<br />

their strong, slightly cloying odor.<br />

Her husb<strong>and</strong> waits in the lobby with the luggage while the<br />

hotel manager opens the safe for her <strong>and</strong> takes out the box. The<br />

wife puts the lire in the box <strong>and</strong> takes the key. She keeps the<br />

travellers' cheques in her h<strong>and</strong>bag.<br />

The wife looks around their big white-washed room. She<br />

admires the painted iron bedstead, the armchair covered in bright<br />

yellow linen <strong>and</strong> the embroidered cotton framed on the walls. She<br />

walks out onto the ver<strong>and</strong>a into the sunlight <strong>and</strong> gazes at the pool<br />

below, which is shadowed by palms, purple bougainvillea, <strong>and</strong> pink<br />

<strong>and</strong> white ole<strong>and</strong>er. She says, "It's lovely, so lovely here, isn't it?"<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "You don/t miss the house at all, do you?"<br />

The wife shakes her head. "No, I don't, actually. Funny isn't<br />

it? I have always preferred hotels, anyway. You don't have to make<br />

your bed," she says. She picks up her h<strong>and</strong>bag with the travellers'<br />

cheques, opens <strong>and</strong> closes the drawers <strong>of</strong> the dresser <strong>and</strong> the<br />

cupboard doors. There is nothing that locks. She hunts in her<br />

h<strong>and</strong>bag for a pen. She says, "I ought to write a postcard. Why<br />

don't you wait for me downstairs?"<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "Write the postcard later. We'll miss the<br />

boat."<br />

The wife puts the h<strong>and</strong>bag on the yellow chair by the door<br />

<strong>and</strong> slips on her navy blue swimsuit, her new light blue towelling<br />

shorts, <strong>and</strong> her expensive, gaily-colored, high-heeled s<strong>and</strong>als. She<br />

looks at her slim brown legs in the mirror, ties back her blond hair,<br />

<strong>and</strong> rubs cream into the lines <strong>of</strong> her upper lip.<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> watches her <strong>and</strong> says, "I am glad you are happy."<br />

He picks up the key to the room <strong>and</strong> the basket with the food for<br />

the picnic. The wife picks up her h<strong>and</strong>bag. The husb<strong>and</strong> says,<br />

"Leave your h<strong>and</strong>bag here. You won't need it on the beach."<br />

The wife smiles nervously <strong>and</strong> says, "Oh, I think I'll just take<br />

it along with me."<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "All right, then give it to me," <strong>and</strong> puts the<br />

h<strong>and</strong>bag into the basket with the key to the safe <strong>and</strong> the bottled<br />

water <strong>and</strong> the prosciutto s<strong>and</strong>wiches for the picnic. The wife takes<br />

the basket from her husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> slings it over her shoulder.<br />

They walk across the wide piazza <strong>and</strong> down the steps to the<br />

pier where the small motor launch is waiting in the calm, clear<br />

water. The boat-driver wears starched white shorts <strong>and</strong> a white<br />

shirt <strong>and</strong> clean white shoes. He smiles at them. He has a<br />

mustache <strong>and</strong> a healthy, reddish face. He takes the wife's h<strong>and</strong> to<br />

help her into the launch. She steps unsteadily into it in her high<br />

heels. She turns to take the basket from the husb<strong>and</strong> who passes<br />

it precariously, she thinks, over the water to her. She sways <strong>and</strong><br />

29

then sits down, clutching the basket to her chest. The husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

wife sit closely, side by side, as the launch moves out slowly<br />

through deep blue water. The spray rises in the air. The rocks<br />

glisten. The low scrub glints, grey-green, spotted with yellow<br />

juniper in the mellow autumn light. The wife says, "This is such<br />

fun." She rises <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>s with the basket slung over her shoulder,<br />

next to the boat-driver. The husb<strong>and</strong> takes the basket from her <strong>and</strong><br />

holds it on his lap. The wife speaks to the boat-driver in Italian:<br />

"What beautiful weather. October is the best time <strong>of</strong> year here."<br />

The boat-driver asks, "You are English, I suppose, <strong>and</strong> your<br />

husb<strong>and</strong> is—an American?"<br />

"Yes, an American," the wife replies.<br />

He asks, "Is this your first time here?"<br />

The wife says, "Oh, no. I have been coming here for years. I<br />

used to have a villa, here, but I sold it last year."<br />

The boat-driver says, "You don't have any <strong>of</strong> the headaches in<br />

a hotel."<br />

The wife says, "Absolutely. I was tied to the villa. There was<br />

always something I had to do to keep it up. I had to pay caretakers<br />

all year round."<br />

The boat-driver opens the throttle <strong>and</strong> says, "This is more<br />

amusing." The spray rises in the air as the launch speeds through<br />

the water <strong>and</strong> bumps over the wide white wake <strong>of</strong> another boat.<br />

The water splashes the wife's face. She laughs <strong>and</strong> licks the salt<br />

from her lips. Her husb<strong>and</strong> says, "Be careful, darling." The wife<br />

sits down beside him <strong>and</strong> puts her h<strong>and</strong> on the basket.<br />

There is a young English couple with a baby in the launch, as<br />

well as an older woman from Texas who films the rocky coast line,<br />

talking into the microphone on her camera. The young<br />

Englishwoman wears a transparent black robe <strong>and</strong> blood-red<br />

lipstick. She holds her boy on her lap <strong>and</strong> claps his h<strong>and</strong>s together<br />

as they bump over the swell; he laughs. The Englishwoman says,<br />

"I hear there was a kidnapping here last year."<br />

The wife says, "Yes, a little boy was kidnapped."<br />

The husb<strong>and</strong> says, "Terrible business. The kidnappers held<br />

him for months <strong>and</strong> months. They even cut <strong>of</strong>f his ear <strong>and</strong> sent it<br />

to the parents to extort ransom, before finally releasing him."<br />

The Englishwoman clutches the baby to her chest.<br />

The Texan leans across t© tell the wife that she has traveled<br />

widely through Europe <strong>and</strong> Asia <strong>and</strong> Africa. She has seen Victoria<br />

Falls. She has seen so many places she cannot keep them straight.<br />

When everyone gets out <strong>of</strong> the boat <strong>and</strong> walks onto the white<br />

s<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> the small crescent beach, fringed with wild grasses, she<br />

says, "What water is this? Is this the Adriatic or the Atlantic or<br />

what?" The boat-driver says politely, "This is the Mediterranean,<br />

Signora."<br />

Apart from the Texan, the young English couple with the<br />

baby, <strong>and</strong> a man who sleeps, or seems to sleep, on a deckchair in<br />

the sun, they are the only people on the beach. The boat-driver<br />

pulls out the deck chairs so that they face the sun <strong>and</strong> retreats to<br />

the shade <strong>of</strong> a small cane hut up the hill, where he prepares his<br />

lunch. The wife can smell the ragu. It makes her suddenly hungry.<br />

She suggests they eat their prosciutto s<strong>and</strong>wiches, but the husb<strong>and</strong><br />

says he is not hungry yet.<br />

The sun is warm, but there is an occasional cloud that passes<br />

<strong>and</strong> casts a shadow over the beach. The wife stretches out in her<br />

deck chair <strong>and</strong> takes out a book from her basket. She sighs, "This<br />

is the life." She watches the husb<strong>and</strong> walking fast along the edge<br />

<strong>of</strong> the languid sea. It is very quiet: only the slight lapping <strong>of</strong><br />

waves—hardly waves, little ripples—can be heard <strong>and</strong> the faint<br />

stirring <strong>of</strong> the breeze in the long grasses.<br />

The wife slips her finger into her h<strong>and</strong>bag <strong>and</strong> feels for the<br />

thick wad <strong>of</strong> travellers' cheques. For a moment she thinks they are<br />

not there. She has not even taken the time to mark down the<br />

serial numbers. Then she finds them. She feels the sun go behind<br />

a cloud <strong>and</strong> looks up at her husb<strong>and</strong>, whose shadow has fallen<br />

onto her. He says, "Why don't we take a run before we eat—<strong>and</strong><br />

think <strong>of</strong> dinner tonight!"<br />

The wife says, "What about our things? We can't just leave<br />

them here." The husb<strong>and</strong> smiles <strong>and</strong> shakes his head at her.<br />

He says, "Of course we can. No one is going to touch our<br />

things."

"Well, you never know for sure," the wife says <strong>and</strong> looks along<br />

the beach at the young couple playing with their baby <strong>and</strong> the<br />

sleeping man. The Texan has already moved on, taken the boat<br />

back to the hotel. The wife pulls on her running shoes, <strong>and</strong> when<br />

her husb<strong>and</strong> is not looking, quickly slips the travellers' cheques out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the h<strong>and</strong>bag <strong>and</strong> puts them in the pocket <strong>of</strong> her towelling<br />

shorts. The pocket is not quite large enough for them. She covers<br />

them with her h<strong>and</strong>, smiles at the husb<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> begins to walk up<br />

the hill. He runs ahead <strong>of</strong> her along the steep white dust path that<br />

leads up into the scrub-covered hills. She follows, running along<br />

the path in the sun. She sweats <strong>and</strong> finds it difficult to run with<br />

her h<strong>and</strong> on her pocket. She lets it go, now <strong>and</strong> then checking to<br />

see if the money is still there. She stops a moment <strong>and</strong> tries<br />

bending the cheques to fit them better into the pocket but is afraid<br />

<strong>of</strong> damaging them. She thinks <strong>of</strong> pushing them down the front <strong>of</strong><br />

her bathing suit but fears the ink may run.<br />

At the top <strong>of</strong> the hill she looks down at another small white<br />

beach below. The water is completely transparent, a pale turquoise<br />

at the edge, <strong>and</strong> she can see the white s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the even sweep <strong>of</strong><br />

the beach like the smooth arc <strong>of</strong> a bow. Not a breath stirs, not a<br />

leaf moves. No one is in sight; she could be the first person taking<br />

possession <strong>of</strong> the place. She is very hot now <strong>and</strong> sweating heavily.<br />

She runs down the hill to the deserted beach. She takes <strong>of</strong>f the<br />

shorts <strong>and</strong> leaves them on a rock, plunging into the cool water. It<br />

is very salty <strong>and</strong> buoyant. She swims out, turning onto her back<br />

from time to time to keep the shorts in view, then strikes out for<br />

the horizon. When she comes back to the beach, she finds her<br />

husb<strong>and</strong> there, waiting for her in the shade <strong>of</strong> a pine tree. Beside<br />

him lie her shorts with the cheques.<br />

For a moment the wife thinks the sun has simply gone behind<br />

a cloud. Then she realizes it has sunk behind the hills. Under the<br />

arcades the husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> wife walk arm <strong>and</strong> arm in the gathering<br />

gloom. The day has ended early, still <strong>and</strong> calm. There is not a<br />

breath <strong>of</strong> wind. They hear the echo <strong>of</strong> their footsteps on the stone.<br />

In the dim light the wife notices certain cracks in the whitewashed<br />

walls, <strong>and</strong> the colors <strong>of</strong> the paint take on a fake glow. At this season<br />

the place looks what it is, a recent development, ephemeral, in a<br />

perdurable l<strong>and</strong>. They pass the Texan who walks by with her<br />

camera around her neck.--?She waves gaily to them <strong>and</strong> says loudly,<br />

"I am seventy-two, but I am still having fun."<br />

The shops are garishly lit under the arcades <strong>and</strong> filled with<br />

expensive goods. The wife says, "You should at least buy yourself<br />

some shoes."<br />

"No, no, I have enough shoes," the husb<strong>and</strong> replies.<br />

The wife sees an expensive black sweater, tailored at the waist;<br />

a bright red scarf, strewn with flowers; a tie with a pattern <strong>of</strong> blue<br />

boats bobbing on the sea; s<strong>of</strong>t leather shoes in black <strong>and</strong> blue. She<br />

wants everything she sees. She says to the husb<strong>and</strong>, "Meet me<br />

back at the hotel in an hour. I am going to w<strong>and</strong>er around a bit<br />

on my own." She buys everything she has seen, paying with some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the travellers' cheques. When she arrives back in her room, she<br />

slips everything except the tie into her suitcase. When her husb<strong>and</strong><br />

emerges from the shower she gives it to him.<br />

"I'll wear it for the dinner," he says, smiling.<br />

Gianna says, "The glasses are from the villa, Signora. You see<br />

we only use them on special occasions." There are blue wine glasses<br />

from the villa, bottles <strong>of</strong> white wine, frosted with cold, the starched<br />

white tablecloth, <strong>and</strong> pink carnations <strong>and</strong> orange lilies as a center<br />

piece. The wife thinks the colors <strong>of</strong> the flowers clash but murmurs<br />

how festive the table looks. She sees four places set <strong>and</strong> asks about<br />

the caretakers' child. Gianna says they have sent her to her cousins<br />

for the night. "An aperitivo," Michelino says.<br />

They sit on the ver<strong>and</strong>a in wicker chairs <strong>and</strong> stare at the lurid<br />

glare <strong>of</strong> the orange moon on the dark water, <strong>and</strong> the distant lights<br />