19 November programme - London Symphony Orchestra

19 November programme - London Symphony Orchestra

19 November programme - London Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

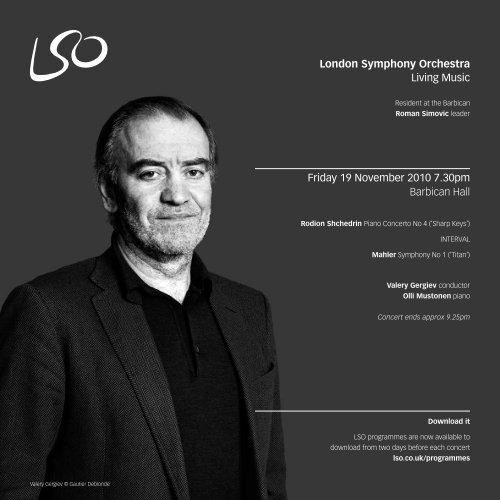

Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

Roman Simovic leader<br />

Friday <strong>19</strong> <strong>November</strong> 2010 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Piano Concerto No 4 (‘Sharp Keys’)<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Titan’)<br />

Valery Gergiev conductor<br />

Olli Mustonen piano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.25pm<br />

Download it<br />

LSO <strong>programme</strong>s are now available to<br />

download from two days before each concert<br />

lso.co.uk/<strong>programme</strong>s

Welcome News<br />

A warm welcome to the Barbican for this evening’s LSO concert which<br />

is dedicated to Maurice Murphy, the LSO’s extraordinary, and much<br />

loved, Principal Trumpet from <strong>19</strong>77–2007.<br />

Tonight, LSO Principal Conductor Valery Gergiev returns to continue<br />

his exploration of the music of fellow Russian Rodion Shchedrin.<br />

We presented Piano Concerto No 5 in September in the LSO’s<br />

season opening concert, and tonight we welcome Finnish pianist<br />

Olli Mustonen to perform the Piano Concerto No 4 (‘Sharp Keys’).<br />

In 2011 Gergiev turns to the music of two more of his countrymen,<br />

Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky. He begins a year-long Tchaikovsky<br />

symphonies cycle with the LSO on 18 January, pairing these with<br />

Shostakovich violin concertos performed by the young Armenian<br />

violinist Sergey Khachatryan making his debut with the LSO, and with<br />

Leonidas Kavakos, making a welcome return in March.<br />

Tomorrow morning the LSO and Gergiev leave on tour to Japan for a<br />

fortnight, where they will perform <strong>programme</strong>s of Mahler and Sibelius<br />

in Tokyo, Osaka and a number of other cities. I hope you can join us<br />

for the <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s return to the Barbican on 5 December when we<br />

see a different side to Mahler.<br />

Tonight’s concert features Mahler’s First <strong>Symphony</strong> – an appropriate<br />

tribute to Maurice Murphy’s memorable performances with the LSO,<br />

and to the great tradition of British brass playing which he championed.<br />

Kathryn McDowell LSO Managing Director<br />

2 Welcome & News<br />

Donatella Flick Conducting Competition – 2010 winner<br />

Congratulations to Clemens Schuldt, winner of the 2010 final of the<br />

Donatella Flick Conducting Competition, held at the Barbican on<br />

4 <strong>November</strong>. As a key part of his prize, 27-year-old German conductor<br />

Clemens will become Assistant Conductor of the LSO for the next two<br />

years. He was awarded the prize by HRH The Duke of Kent, Donatella<br />

Flick and a distinguished international jury. In the final, he conducted<br />

the LSO in Johann Strauss’s Overture to Die Fledermaus and Wagner’s<br />

Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde.<br />

www.conducting.org<br />

LSO String Experience Scheme<br />

Congratulations also to the 20 young string players who have been<br />

selected from recent auditions to take part in the 2010/11 LSO<br />

String Experience Scheme. The Scheme enables string students<br />

from <strong>London</strong> music conservatoires to gain professional experience<br />

by playing in rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. Participants are<br />

treated as professional ‘extra’ players and are paid for their work in<br />

line with LSO section players. We are very grateful to the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and to Charles and Pascale Clark for their generous<br />

support of the Scheme.<br />

lso.co.uk/stringexperience<br />

Music’s better shared!<br />

There’s never been a better time to bring all your friends to<br />

an LSO concert. Groups of 10+ receive a 20% discount on<br />

all tickets, plus a host of additional benefits.<br />

Call the dedicated Group Booking line on 020 7382 7211,<br />

visit lso.co.uk/groups or email groups@barbican.org.uk<br />

The LSO is delighted to welcome the following groups tonight:<br />

Gerrards Cross Community Association<br />

King Edward VI Grammar School, Chelmsford<br />

Mariinsky Theatre Trust<br />

MAURICE<br />

MURPHY<br />

<strong>19</strong>35–2010<br />

LSO Principal Trumpet: <strong>19</strong>77–2007<br />

A tribute by LSO Chairman<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Maurice Murphy was a truly extraordinary<br />

and wonderful man who inspired us all.<br />

He inspired us not only when he put his beloved trumpet to his lips<br />

to create that pure, thrilling and golden sound that we all know and love;<br />

but he inspired us also with his very inner being, displaying generosity<br />

of spirit, care, and love to one and all. Maurice was in short a musical<br />

giant, a loving family man, a true gem and everyone’s hero. He was<br />

also extremely modest, often saying ‘I’m just another trumpet player –<br />

I’ve been very lucky’. Well, I think everyone who has met Maurice has<br />

been lucky, to have known this great, humble and special man.<br />

Maurice was born in <strong>London</strong>, however, four years later war broke<br />

out and the family returned to the North of England. There were<br />

many brass bands in the area, so Maurice used to say it was just<br />

‘natural’ that he took up the instrument, which he did when he<br />

was six. He played with his Dad in the West Stanley Salvation Army<br />

Band in County Durham, and by twelve he had won the All Britain<br />

Cornet Championships.<br />

Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik Maurice Murphy 3

Maurice Murphy remembered<br />

Maurice became Principal Cornet with the Fairey Aviation Band and<br />

subsequently received the top job, the highest accolade in the Brass<br />

Band world – Principal Cornet of the Black Dyke Mills Band. His time<br />

there is still remembered with huge affection and admiration, and his<br />

presence remains in Northern brass band folklore and legend.<br />

He started playing with the local orchestras<br />

including the Hallé, the Royal Liverpool<br />

Philharmonic and the BBC Northern (now the<br />

BBC Philharmonic), and also enjoyed gigs in<br />

theatres and dance bands. Yorkshire choral<br />

societies used to stagger their traditional<br />

Christmas performances of Handel’s Messiah<br />

so that Maurice could play ‘The Trumpet Shall<br />

Sound’ in all of them.<br />

Maurice with his father Billy<br />

front second and third from right He joined the BBC Northern and stayed with<br />

Crookhall Band, Oct <strong>19</strong>51<br />

them for 16 years, ignoring various attempts<br />

to lure him down to <strong>London</strong>. Eventually, he accepted a trip to Mexico<br />

with the LSO and was often spotted wandering the Mexico City streets<br />

wearing a sombrero. Consequently he was offered the position of<br />

Principal Trumpet of the LSO which he accepted, little realising that his<br />

first engagement with the <strong>Orchestra</strong> as a member would bring him<br />

worldwide acclaim and international stardom.<br />

John Williams was in town and the LSO was recording the music<br />

for Star Wars. Maurice was cast straight into ‘Opening Titles’ with<br />

its heroic, diamond-sharp fanfares and blistering top Cs. He stamped<br />

his very own imprint and sound on the music, which still takes your<br />

breath away over three decades later, and instantly he gained<br />

legendary status. John Williams, ‘The Governor’ as Maurice called<br />

him, was over the moon with the performance and returned for<br />

many more films with Maurice’s sound very much in mind as he<br />

put pen to paper. Maurice alone was responsible for Hollywood<br />

bringing major film scores to be recorded here in Britain, benefiting<br />

thousands of UK musicians.<br />

Maurice was a totally natural player. He would amaze his colleagues<br />

by walking onto the stage without having warmed up or played a note,<br />

and produce an immaculate Mahler Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>. He also had the<br />

unique ability to lift the <strong>Orchestra</strong> single-handedly and to stimulate it<br />

to greater things. Sir Colin Davis remembers an especially exhausted<br />

LSO playing Sibelius on a Russian tour: ‘We needed a lift from<br />

somewhere’, he said, ‘I looked at Maurice who gave me a big smile,<br />

picked up the LSO and made me a present of it’.<br />

But the part of Maurice’s make-up I shall always remember him most<br />

for was his care and concern for his fellow man. He loved, protected<br />

and cared for his section like no other.<br />

On one occasion we were in Chicago and there was an icy blizzard<br />

blowing. Outside <strong>Symphony</strong> Hall a tuba player was busking. Maurice<br />

was concerned for the player, thinking he could do himself some<br />

harm, so a spontaneous collection was made from the brass players<br />

and as Maurice was not in the first half he was despatched to give<br />

the tuba player the money. The next time we saw Maurice was at the<br />

interval, his leg and foot heavily bandaged, limping and walking with a<br />

stick! He had handed over the money and then had promptly slipped<br />

over in the icy snow. For the rest of the tour the trumpet section took<br />

it in turns to push Maurice around in a wheelchair, but the cold tuba<br />

player enjoyed his early finish in the warm.<br />

Maurice loved American tours but nowhere more so than Daytona<br />

Beach. The golf courses are sensational there and Maurice had<br />

designed the trumpet box intended to carry his instruments around<br />

the world with space for his golf clubs. It was a joy to watch Maurice<br />

in his element sweetly striking his golf ball far down the fairway.<br />

When Maurice was present, there was always humour and lots of<br />

jokes. We were rehearsing one day in Daytona and all of a sudden<br />

the lights went out and the hall was plunged into darkness. It all went<br />

quiet and Maurice’s voice was heard saying ‘Bad play stops light’.<br />

Maurice thrilled us at the LSO for 30 glorious years and was much<br />

in demand in the freelance world too, where he absolutely loved to<br />

join trumpeters from the jazz and light music world, making many<br />

close friendships.<br />

When the time came for Maurice to retire, nobody wished for that<br />

to happen. It was premature. We all loved him and he was playing<br />

as well as ever, if not better. So every year for seven years he was<br />

asked to stay for another year, with the unanimous backing of the<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> members.<br />

At his final retirement party – and there were many – Maurice was<br />

asked to say a few words. ‘I hate making speeches’, he said, ‘I’d rather<br />

play another Mahler Five’. He intimated he found the travelling harder<br />

and said, ‘Anyway, I thought I would award myself with the DCM<br />

before someone else does’. DCM? ‘Don’t Come Monday’. Little did<br />

Maurice realise that a real award was on the way, a most deserved<br />

MBE in recognition of services to music.<br />

Maurice was never happier than when being with his wife Shirley<br />

and their family, his son Martin and his wife Helen and their son Sam.<br />

It was earlier this year that Maurice and Shirley celebrated their<br />

golden wedding anniversary.<br />

Maurice has touched us all. His memory will live with us forever.<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Maurice Murphy<br />

<strong>19</strong>35 Born in Hammersmith<br />

<strong>19</strong>41 Began studying the cornet<br />

<strong>19</strong>47 Became All England Juvenile Solo Champion<br />

<strong>19</strong>56–61 Solo Cornet with Black Dyke Mills Band<br />

<strong>19</strong>61–76 Principal Trumpet with the BBC Northern<br />

Feb 77 Joined the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> as Principal Trumpet<br />

Mar 77 LSO recorded Star Wars with Maurice Murphy playing solo<br />

trumpet on his first day with the <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Jun 07 Retired from the LSO<br />

2008 Received the Honorary Award of the International Trumpet<br />

Guild, ‘given to those who have made extraordinary<br />

contributions to the art of trumpet playing’<br />

2010 Awarded an MBE in the New Year’s Honours List<br />

4 Maurice Murphy<br />

Photos © Clive Barda, Robert Hill, Anthony Haas<br />

Maurice Murphy 5

Rodion Shchedrin (b <strong>19</strong>32)<br />

Piano Concerto No 4 (‘Sharp Keys’) (<strong>19</strong>91)<br />

1 Sostenuto cantabile – Allegretto – Sostenuto<br />

2 ‘Russian Chimes’ – Allegro<br />

Olli Mustonen piano<br />

Since Prokofiev and Shostakovich the number of front-rank<br />

composers who could also claim to be first-rate concert pianists has<br />

dwindled remarkably, and of the remaining few, hardly any have made<br />

piano music as strong a feature of their output as Rodion Shchedrin.<br />

Trained as a composer under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under<br />

Yakov Flier, he has composed six piano concertos to date, as well as<br />

a substantial body of solo piano works.<br />

In this area Shchedrin has generally shown more affinity for<br />

Prokofiev than for Shostakovich, especially in the concertos, which<br />

at least initially were marked by vivid colours, forceful energy and<br />

total absence of self-doubt. His First Piano Concerto, for instance,<br />

a graduation piece from <strong>19</strong>54, was an extrovert romp that could have<br />

been designed as a tribute to Prokofiev, who had died the previous<br />

year. Twelve years later, the Second Concerto retained that influence,<br />

alongside a playful indulgence in twelve-note techniques. However,<br />

nearly 20 years separate the first three piano concertos, all of which<br />

Shchedrin premiered and recorded with himself as soloist, from the<br />

last three (No 3 was composed in <strong>19</strong>73, No 4 in <strong>19</strong>91 to a commission<br />

from the Steinway Foundation). In this second phase, exhibitionism<br />

gives way to a more private, exploratory tone.<br />

According to the composer, ‘The entire [Fourth Piano Concerto] is<br />

in the sharp keys; there is not a single flat in the score’. This is true,<br />

though the ‘sharp keys’ are rarely heard in anything approaching<br />

their pure form. Rather, the first movement, for instance, is poised<br />

somewhere on the arc between A, E, and B majors. Shchedrin’s<br />

explanation for his compositional conceit is somewhat curious:<br />

‘This is both a conscious self-limitation (my own form of minimalism)<br />

and at the same time a wish to create the richest possible acoustic<br />

atmosphere for my piano soloist – one saturated with overtones’.<br />

Why he should consider sharp keys to contain more overtones than<br />

flat ones remains a mystery.<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

The first movement is dominated by the piano’s rhapsodic roulades,<br />

reminiscent of the trance-like slow movement of Michael Tippett’s<br />

Piano Concerto. A brief spiky dialogue and a soliloquising transition<br />

lead into a central Allegretto that develops into an episode of<br />

toccata-like brilliance, interspersed with more martial figures (marked<br />

‘fanfare-like’). A dismissive downward flourish on the piano concludes<br />

the movement, at the same time as providing the material for the<br />

second movement, headed ‘Russian Chimes’.<br />

Here Shchedrin’s explanation is entirely pertinent: ‘I wanted to include<br />

… the ‘alphabet’ of Ancient Russian change-ringing … Here I have<br />

in mind the ringing of holidays, celebratory, paschal, what in Russian<br />

is so appropriately called by the wonderful word blagovest – Glad<br />

Tidings’. It is in this movement, too, that he realises his intent to make<br />

‘full use of the extreme registers of the piano … so especially bright<br />

and ringing in the Steinway’. The increasingly manic tintinnabulations<br />

eventually give way to a return of the Sostenuto cantabile mood from<br />

the first movement, albeit now carrying a calm version of the ‘Chimes’<br />

theme. The piano then offers a musing postscript before the orchestra<br />

joins in to give the concerto an applause-inviting send-off.<br />

Programme note © David Fanning<br />

David Fanning is Professor of Music at the University of Manchester.<br />

He is an expert on Shostakovich, Nielsen and Soviet music. He is<br />

also a reviewer for the Daily Telegraph, Gramophone Magazine and<br />

BBC Radio 3.<br />

INTERVAL: 20 minutes<br />

Rodion Shchedrin (b <strong>19</strong>32)<br />

The Man<br />

The generation of Soviet composers after Shostakovich produced<br />

charismatic and exotic figures such as Galina Ustvolskaya,<br />

Alfred Schnittke and Sofiya Gubaydulina, whose music was initially<br />

controversial but then gained cult status. At the other end of the<br />

stylistic spectrum it featured highly gifted craftsmen such as<br />

Boris Tishchenko, Boris Tchaikovsky and Mieczysław Weinberg, all<br />

of whom worked more or less within the parameters laid down by<br />

Shostakovich and were highly respected in their heyday but gradually<br />

fell from favour.<br />

Somewhere in between we can locate Rodion Shchedrin – an<br />

individualist with a broader and more consistent appeal, who could<br />

turn himself chameleon-like to virtuoso pranks or to profound<br />

philosophical reflection, to Socialist Realist opera or to folkloristic<br />

Concertos for <strong>Orchestra</strong> (a particular speciality), to technically solid<br />

Preludes and Fugues, to jazz, and, when he chose, even to twelvenote<br />

constructivism.<br />

Trained at the Moscow Conservatoire in the <strong>19</strong>50s, as a composer<br />

under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under Yakov Flier in the early<br />

years of the Post-Stalinist Thaw, Shchedrin was one of<br />

the first to speak out against the constraints of<br />

musical life in the Soviet Union. He went on to play<br />

a significant administrative role in the country’s<br />

musical life, heading the Russian Union of Composers<br />

from <strong>19</strong>73 to <strong>19</strong>90. Married since <strong>19</strong>58 to the star<br />

Soviet ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, he established a<br />

significant power-base from which he was able to promote<br />

not only his own music but also that of others – such as<br />

Schnittke, whose notorious First <strong>Symphony</strong> received its<br />

sensational premiere only thanks to Shchedrin’s support.<br />

An unashamed eclectic, and suspicious of dogma from<br />

either the arch-modernist or arch-traditionalist wings of<br />

Soviet music, Shchedrin occupied a not always comfortable<br />

position, both in his pronouncements and in his creative<br />

work. With one foot in the national-traditional camp and the<br />

other in that of the internationalist-progressives, he was<br />

tagged with the unkind but not unfair label of the USSR’s<br />

Rodion Shchedrin © www.lebrecht.co.uk<br />

‘official modernist’. From <strong>19</strong>92 he established a second home in<br />

Munich, but he still enjoyed official favour in post-Soviet Russia,<br />

adding steadily to his already impressive roster of prizes.<br />

Shchedrin has summed up his artistic credo as follows: ‘I continue to<br />

be convinced that the decisive factor for each composition is intuition.<br />

As soon as composers relinquish their trust in this intuition and rely in<br />

its place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism, aleatoric composition,<br />

minimalism or other methods, things become problematic.’<br />

Programme Notes<br />

7

Gustav Mahler (1860–<strong>19</strong>11)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 in D major (‘Titan’) (1884–88, rev 1893–96)<br />

1 Langsam. Schleppend [Slow. Dragging] – Immer sehr gemächlich<br />

[Always at a very leisurely pace]<br />

2 Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell [With strong movement,<br />

but not too fast] – Trio: Recht gemächlich [Quite leisurely] –<br />

Tempo primo<br />

3 Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen [Solemn and<br />

measured, without dragging]<br />

4 Stürmisch bewegt [Stormy]<br />

When Gustav Mahler began his First <strong>Symphony</strong> in 1884, ‘modern<br />

music’ meant Wagner, while the standard by which new symphonies<br />

were judged was that of Brahms, the arch ‘classical-romantic’.<br />

In a Brahmsian symphony there was little room for Wagnerian<br />

lush harmonies, or sensational new orchestral colours. In fact the<br />

orchestral forces Brahms employed were basically the same as those<br />

used by Beethoven and Schubert in their symphonies, three-quarters<br />

of a century earlier.<br />

So for audiences brought up on Brahms, hearing Mahler’s First<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> would have been like stepping into a new world. The<br />

opening can still surprise even today: one note, an A, is spread<br />

through almost the entire range of the string section, topped with<br />

ghostly violin harmonics. Other unusual colours follow: distant<br />

trumpet fanfares, high clarinet cuckoo-calls, a plaintive cor anglais,<br />

the bell-like bass notes of the harp. All this would have been startlingly<br />

new in Mahler’s time. And there’s nothing tentative or experimental<br />

about this symphonic debut: at 24, Mahler knows precisely the sound<br />

he wants, and precisely how to get it.<br />

Still, there’s much more to Mahler’s First <strong>Symphony</strong> than innovative<br />

orchestral colours and effects. When the symphony was first<br />

performed it had a title, ‘Titan’ – taken from the once-famous novel by<br />

the German romantic writer Jean Paul (the pen name of Johann Paul<br />

Richter). For Richter the ‘Titan’, the true genius, is a ‘Heaven-Stormer’<br />

(Himmelsstürmer) an obsessive, almost recklessly passionate idealist.<br />

The idea appealed strongly to Mahler, but so too did Richter’s vividly<br />

poetic descriptions of nature. For the premiere, Mahler set out his<br />

version of the Titan theme in an explanatory <strong>programme</strong> note, which<br />

told how the symphony progressed from ‘the awakening of nature<br />

at early dawn’, through youthful happiness and love, to the sardonic<br />

gloom of the funeral march, and then to the finale, subtitled ‘From<br />

Inferno to Paradise’. And it was clear that Mahler’s interest in Richter’s<br />

theme was more than literary. Behind the symphony, he hinted to<br />

friends, was the memory of a love affair that had ended, painfully, at<br />

about the time he began work on the symphony.<br />

But Mahler soon began to lose faith in <strong>programme</strong>s. ‘I would like it<br />

stressed that the symphony is greater than the love affair it is based<br />

on’, he wrote. ‘The real affair became the reason for, but by no means<br />

the true meaning of, the work.’ In later life he could be blunt: when<br />

someone raised the subject at an evening drinks party, Mahler is<br />

said to have leapt to his feet and shouted, ‘Perish all <strong>programme</strong>s!’<br />

But for most listeners, music that is so passionate, dramatic and so<br />

full of the sounds of nature can’t be fully explained in the detached<br />

terms of ‘pure’ musical analysis. Fortunately the First <strong>Symphony</strong> is<br />

full of pointers to possible meanings beyond the notes. The main<br />

theme of the first movement – heard on cellos and basses after the<br />

slow, intensely atmospheric ‘dawn’ introduction – is taken from the<br />

second of Mahler’s four Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (‘Songs<br />

of a Wayfarer’), written as a ‘memorial’ to his affair with the singer<br />

Johanna Richter (no relation of the novelist, but the name connection<br />

is striking). In the song, a young man, jilted in love, sets out on a<br />

beautiful spring morning, hoping that nature will help his own heart<br />

to heal. For most of the first movement, Mahler seems to share the<br />

young man’s hope. The ending seems cheerful enough. But at the<br />

heart of the movement comes a darkly mysterious passage, echoing<br />

the ‘dawn’ introduction, but adding sinister new sounds: the low, quiet<br />

growl of a tuba, ominous drum-beats, and a repeated sighing figure<br />

for cellos. For a moment, the music seems to echo the final words<br />

of the song: ‘So will my joy blossom too? No, no; it will never, never<br />

bloom again’.<br />

Dance music dominates the second movement, especially the robust,<br />

earthy vigour of the Ländler (the country cousin of the sophisticated<br />

urban Waltz). There are hints here of another, earlier song, Hans und<br />

Grete, in which gawky young Hans finds a sweetheart at a village<br />

dance – all innocent happiness. But the slower, more reflective Trio<br />

brings more adult expression: nostalgia and, later, sarcasm (shrill high<br />

woodwind). The third movement is in complete contrast. This is an<br />

eerie, sardonic funeral march, partly inspired by a painting by Jacques<br />

Callot, ‘The Huntsman’s Funeral’, in which a procession of animals<br />

carry the hunter to his grave. One by one, the orchestral instruments<br />

enter quietly, playing a famous old nursery tune, Frère Jacques –<br />

which sounds like another interesting name connection, except<br />

that Austrians like Mahler would have known the tune to the words<br />

‘Brother Martin, are you sleeping?’ At the heart of this movement,<br />

Mahler makes a lengthy quotation from the last of the Lieder eines<br />

fahrenden Gesellen. The song tells in soft, gentle tones of how a<br />

young man, stricken with grief at the loss of the girl he loves, finds<br />

consolation in the thought of death. This is the dark heart of the<br />

First <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

But this is not the end of the story. In the finale Mahler strives<br />

onward – in the words of the discarded <strong>programme</strong>, ‘From Inferno<br />

to Paradise’. At first all is turbulence, but when the storm has died<br />

down, strings present an ardent, slower melody – unmistakably a love<br />

theme. There’s a brief memory of the first movement’s ‘dawn’ music,<br />

then the struggle begins again. Eventually massed horns introduce<br />

a new, radiantly hopeful theme, strongly reminiscent of ‘And he shall<br />

reign’ from Handel’s Messiah. More reminiscences and still more<br />

heroic struggles follow, until dark introspection is finally overcome,<br />

and the symphony ends in jubilation. Mahler’s hero has survived to<br />

live, and love, another day.<br />

Programme note © Stephen Johnson<br />

Stephen Johnson is the author of Bruckner Remembered (Faber).<br />

He also contributes regularly to the BBC Music Magazine and<br />

The Guardian, and broadcasts for BBC Radio 3 (Discovering Music),<br />

Radio 4 and the World Service.<br />

Gustav Mahler (1860–<strong>19</strong>11)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Gustav Mahler’s early experiences of music were influenced by the<br />

military bands and folk singers who passed by his father’s inn in<br />

the small town of Iglau (the German name for Jihlava in what is now<br />

the Czech Republic). Besides learning many of their tunes, he also<br />

received formal piano lessons from local musicians and gave his first<br />

recital in 1870. Five years later, he applied for a place at the Vienna<br />

Conservatory where he studied piano, harmony and composition.<br />

After graduation, Mahler supported himself by teaching music and<br />

also completed his first important composition, Das klagende Lied.<br />

He accepted a succession of conducting posts in Kassel, Prague,<br />

Leipzig and Budapest; and the Hamburg State Theatre, where he<br />

served as First Conductor from 1891–97. For the next ten years,<br />

Mahler was Resident Conductor and then Director of the prestigious<br />

Vienna Hofoper.<br />

The demands of both opera conducting and administration meant<br />

that Mahler could only devote the summer months to composition.<br />

Working in the Austrian countryside he completed nine symphonies,<br />

richly Romantic in idiom, often monumental in scale and extraordinarily<br />

eclectic in their range of musical references and styles. He also<br />

composed a series of eloquent, often poignant songs, many themes<br />

from which were reworked in his symphonic scores. An anti-Semitic<br />

campaign against Mahler in the Viennese press threatened his<br />

position at the Hofoper, and in <strong>19</strong>07 he accepted an invitation to<br />

become Principal Conductor of the Metropolitan Opera and later the<br />

New York Philharmonic. In <strong>19</strong>11 he contracted a bacterial infection<br />

and returned to Vienna. When he died a few months before his 51st<br />

birthday, Mahler had just completed part of his Tenth <strong>Symphony</strong> and<br />

was still working on sketches for other movements.<br />

Profile © Andrew Stewart<br />

8 Programme Notes Programme Notes 9

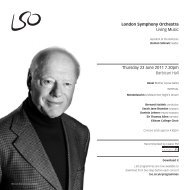

Valery Gergiev<br />

Conductor<br />

Principal Conductor of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> since January 2007, Valery Gergiev<br />

performs regularly with the LSO at the<br />

Barbican, at the Proms and at the Edinburgh<br />

Festival, as well as regular tours of Europe,<br />

North America and Asia. During the 2010/11<br />

season he will lead them in appearances in<br />

Germany, France, Switzerland, Japan and<br />

the USA.<br />

Valery Gergiev is Artistic and General<br />

Director of the Mariinsky Theatre, founder<br />

and Artistic Director of the Stars of the<br />

White Nights Festival and New Horizons<br />

Festival in St Petersburg, the Moscow Easter<br />

Festival, the Gergiev Rotterdam Festival, the<br />

Mikkeli International Festival, and the Red<br />

Sea Festival in Eilat, Israel. He succeeded<br />

Sir Georg Solti as conductor of the World<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> for Peace in <strong>19</strong>98 and leads them<br />

this season in concerts in Abu Dhabi.<br />

His inspired leadership of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre since <strong>19</strong>88 has taken the Mariinsky<br />

ensembles to 45 countries and has brought<br />

universal acclaim to this legendary institution,<br />

now in its 227th season. Having opened a<br />

new concert hall in St Petersburg in 2006,<br />

Maestro Gergiev looks forward to the opening<br />

of the new Mariinsky Opera House in the<br />

summer of 2012.<br />

Born in Moscow, Valery Gergiev studied<br />

conducting with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory. Aged 24 he won the Herbert<br />

von Karajan Conductors’ Competition in<br />

Berlin and made his Mariinsky Opera debut<br />

one year later in <strong>19</strong>78 conducting Prokofiev’s<br />

War and Peace. In 2003 he led St Petersburg’s<br />

300th anniversary celebrations, and opened<br />

the Carnegie Hall season with the Mariinsky<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the first Russian conductor to do<br />

so since Tchaikovsky conducted the Hall’s<br />

inaugural concert in 1891.<br />

Now a regular figure in all the world’s major<br />

concert halls, he will lead the LSO and<br />

the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> in a symphonic<br />

Centennial Mahler Cycle in New York in the<br />

2010/11 season. He has led several cycles in<br />

New York including Shostakovich, Stravinsky,<br />

Prokofiev, Berlioz and Richard Wagner’s Ring.<br />

He has also introduced audiences to several<br />

rarely-performed Russian operas.<br />

Valery Gergiev’s many awards include a<br />

Grammy, the Dmitri Shostakovich Award,<br />

the Golden Mask Award, People’s Artist of<br />

Russia Award, the World Economic Forum’s<br />

Crystal Award, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize,<br />

Netherlands’s Knight of the Order of the Dutch<br />

Lion, Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Valencia’s<br />

Silver Medal, the Herbert von Karajan prize and<br />

the French Order of the Legion of Honour.<br />

He has recorded exclusively for Decca<br />

(Universal Classics), and appears also on<br />

the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon<br />

labels. Currently recording for LSO Live, his<br />

releases include Mahler Symphonies Nos<br />

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8, Rachmaninov <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

No 2, Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet and Bartók<br />

Bluebeard’s Castle.<br />

His recordings on the newly formed Mariinsky<br />

Label are Shostakovich The Nose and<br />

Symphonies Nos 1, 2, 11 & 15, Tchaikovsky’s<br />

1812 Overture, Rachmaninov Piano Concerto<br />

No 3 and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini,<br />

Shchedrin The Enchanted Wanderer,<br />

Stravinsky Les Noces and Oedipus Rex,<br />

many of which have won awards including<br />

four Grammy nominations. The most recent<br />

release was Wagner Parsifal (September<br />

2010), featuring René Pape and Gary Lehman.<br />

Valery Gergiev conducts<br />

Tue 18 & Sun 23 Jan 7.30pm<br />

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No 2<br />

with Sergey Khachatryan violin<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1<br />

Wed 2 & Thu 3 Mar 7.30pm<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 9<br />

Wed 23 & Thu 24 Mar 7.30pm<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Lithuanian Saga<br />

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No 1<br />

with Leonidas Kavakos violin<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 2<br />

lso.co.uk (reduced bkg fee)<br />

020 7638 8891 (bkg fee)<br />

Olli Mustonen<br />

Piano<br />

Olli Mustonen occupies a unique position<br />

on today’s music scene. As a pianist, he<br />

has challenged and fascinated audiences<br />

worldwide with his brilliant technique<br />

and startling originality. In his role as a<br />

conductor, he founded the Helsinki Festival<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, and as a composer he forms<br />

part of a distinguished line of musicians<br />

whose vision is expressed as vividly in the<br />

art of interpretation as it is in their own<br />

compositions.<br />

Born in Helsinki, he began studying piano,<br />

harpsichord and composition aged five.<br />

He subsequently studied piano with Eero<br />

Heinonen and composition with Einojuhani<br />

Rautavaara. As a recitalist he has since<br />

played in all the world’s musical capitals,<br />

including Amsterdam, Berlin, <strong>London</strong>,<br />

New York, Tokyo and Vienna.<br />

At the heart of both his piano playing<br />

and conducting is his life as a composer.<br />

Mustonen has a deeply held conviction that<br />

each performance must have the freshness<br />

of a first performance, so that audience and<br />

performer alike encounter the composer as a<br />

living contemporary. His compositions include<br />

works for orchestra, piano concertos, nonets,<br />

solo violin and a song cycle. His tenacious spirit<br />

of discovery leads him to explore many areas of<br />

repertoire beyond the established canon.<br />

As a soloist, Mustonen has worked with many<br />

leading international orchestras, including<br />

the Berlin Philharmonic, Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin,<br />

Cleveland <strong>Orchestra</strong>, <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic,<br />

Los Angeles Philharmonic, Royal<br />

Concertgebouw, Philadelphia <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Philharmonia <strong>Orchestra</strong>, partnering<br />

conductors such as Vladimir Ashkenazy,<br />

Daniel Barenboim, Paavo Berglund, Pierre<br />

Boulez, Myung-Whun Chung, Charles Dutoit,<br />

Christoph Eschenbach, Nikolaus Harnoncourt,<br />

Kurt Masur, Kent Nagano and Jukka-Pekka<br />

Saraste. This season, as well as this evening’s<br />

appearance with the LSO, he also performs<br />

as soloist with the New York Philharmonic<br />

under Esa-Pekka Salonen, Frankfurt Radio<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and the Royal Flemish<br />

Philharmonic.<br />

Increasingly, Olli Mustonen is also making<br />

his mark as a conductor. Recent highlights<br />

include leading the Bern <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, New Jersey <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

and the Queensland <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>;<br />

this season brings engagements with the<br />

Staatskapelle Weimar, West Australian<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and the Melbourne<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>, with whom he<br />

continues his complete cycle of Beethoven<br />

piano concertos as soloist and director.<br />

He also embarks on a recital tour of Italy<br />

with Steven Isserlis in early 2011 and<br />

will finish the season with a recital at the<br />

Edinburgh Festival.<br />

Olli Mustonen’s recording catalogue is<br />

typically broad-ranging and distinctive.<br />

His release on Decca of Preludes by<br />

Shostakovich and Alkan received the Edison<br />

Award and Gramophone Award for the Best<br />

Instrumental Recording. In 2002 Mustonen<br />

signed a recording contract with Ondine.<br />

His releases on the label include Bach and<br />

Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues; a disc<br />

of Sibelius’s piano works; Hindemith and<br />

Sibelius as player-conductor with the Helsinki<br />

Festival <strong>Orchestra</strong>; Mozart violin concertos<br />

with Pekka Kuusisto and Tapiola Sinfonietta;<br />

a selection of Prokofiev’s piano music; and<br />

most recently Rachmaninov Piano Sonata<br />

No 1 and Tchaikovsky The Seasons. He has<br />

just completed recording all the Beethoven<br />

Piano Concertos as soloist/director with the<br />

Tapiola Sinfonietta.<br />

10 The Artists Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

The Artists 11

On stage<br />

First Violins<br />

Roman Simovic Leader<br />

Carmine Lauri<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Nicholas Wright<br />

Nigel Broadbent<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Michael Humphrey<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Laurent Quenelle<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

Hazel Mulligan<br />

Helen Paterson<br />

Alain Petitclerc<br />

Second Violins<br />

David Alberman<br />

Thomas Norris<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

Miya Ichinose<br />

Richard Blayden<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Stephen Rowlinson<br />

Caroline Frenkel<br />

Oriana Kriszten<br />

Roisin Walters<br />

David Worswick<br />

12 The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Violas<br />

Edward Vanderspar<br />

Gillianne Haddow<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Lander Echevarria<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Heather Wallington<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Michelle Bruil<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Fiona Opie<br />

Martin Schaefer<br />

Cellos<br />

Rebecca Gilliver<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Mary Bergin<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Minat Lyons<br />

Amanda Truelove<br />

Penny Driver<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Nicholas Worters<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Matthew Gibson<br />

Thomas Goodman<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Benjamin Griffiths<br />

Nikita Naumov<br />

Flutes<br />

Gareth Davies<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Patricia Moynihan<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Emanuel Abbühl<br />

Joseph Sanders<br />

Fraser MacAulay<br />

Cor Anglais<br />

Christine Pendrill<br />

Clarinets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bass Clarinet<br />

Lorenzo Iosco<br />

E-flat Clarinet<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bassoons<br />

Rachel Gough<br />

Bernardo Verde<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Contra-bassoon<br />

Dominic Morgan<br />

Horns<br />

Timothy Jones<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Estefanía Beceiro Vazquez<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Jeffrey Bryant<br />

Richard Clews<br />

Brendan Thomas<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philip Cobb<br />

Nicholas Betts<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Nigel Gomm<br />

Offstage Trumpets<br />

Christopher Deacon<br />

Edward Hobart<br />

Martin Hurrell<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

Katy Jones<br />

James Maynard<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Tuba<br />

Patrick Harrild<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

Scott Bywater<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

David Jackson<br />

Tom Edwards<br />

Harp<br />

Bryn Lewis<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in <strong>19</strong>92, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

Leah Meredith (first violin),<br />

Mark Lee (second violin) and<br />

Ana Córdova Andrés (double<br />

bass) took part in rehearsals for<br />

tonight’s concert as part of the<br />

LSO String Experience Scheme.<br />

The LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme is generously<br />

supported by the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and Charles<br />

and Pascale Clark.<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450