Sunday 10 June 2012 - London Symphony Orchestra

Sunday 10 June 2012 - London Symphony Orchestra

Sunday 10 June 2012 - London Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

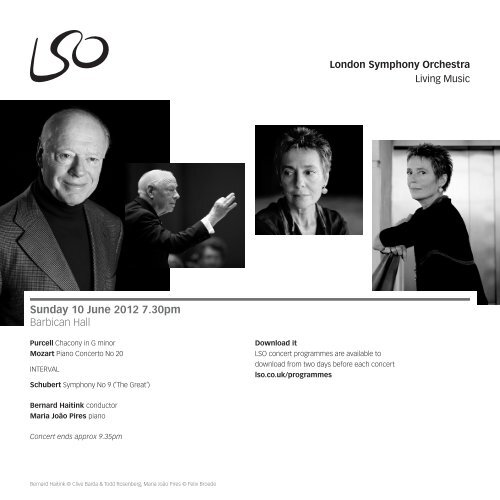

<strong>Sunday</strong> <strong>10</strong> <strong>June</strong> <strong>2012</strong> 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Purcell Chacony in G minor<br />

Mozart Piano Concerto No 20<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Schubert <strong>Symphony</strong> No 9 (‘The Great’)<br />

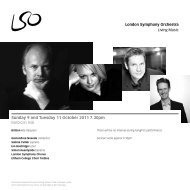

Bernard Haitink conductor<br />

Maria João Pires piano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.35pm<br />

Bernard Haitink © Clive Barda & Todd Rosenberg, Maria João Pires © Felix Broede<br />

Download it<br />

LSO concert programmes are available to<br />

download from two days before each concert<br />

lso.co.uk/programmes<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music

Welcome News<br />

Welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at the Barbican, the first of two<br />

concerts which reunite conductor Bernard Haitink with pianist Maria<br />

João Pires, who last performed with the <strong>Orchestra</strong> in <strong>June</strong> 2011.<br />

Bernard Haitink has a rich history with the LSO and is one of the<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>’s most loved guest conductors. Into the <strong>2012</strong>/13 season,<br />

the LSO looks forward to working with Haitink to present works by<br />

Britten, Mozart, Beethoven and Bruckner across three concerts in<br />

February 2013 (see page 5 for more details). Maria João Pires has<br />

had a highly successful season across Europe and will be joining<br />

Bernard Haitink on tour with the <strong>Orchestra</strong> to perform tonight’s<br />

programme, and the programme for 14 <strong>June</strong>, at Salle Pleyel in Paris<br />

on 17 and 18 <strong>June</strong>.<br />

I hope you enjoy tonight’s concert and can join us for our next<br />

performance on Thursday 14 <strong>June</strong> when Bernard Haitink and<br />

Maria João Pires will join forces once more for Mozart’s Piano<br />

Concerto No 23, alongside Purcell’s Funeral Music for Queen Mary<br />

and Bruckner’s lyrical <strong>Symphony</strong> No 7.<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

Sir Colin Davis awarded Order of the Dannebrog<br />

Congratulations to LSO President Sir Colin Davis, who was bestowed<br />

with a Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog on Friday 25 May.<br />

The decoration is presented to those who make a special contribution<br />

to the public, the arts and sciences in Denmark, and is one of the<br />

oldest orders in existence. Sir Colin Davis was honoured this for his<br />

recordings of Nielsen’s symphonies, recorded with the LSO in 2011.<br />

The award was presented at a ceremony at the Danish Embassy<br />

hosted by the Danish Ambassador, Ms Anne Hedensted Steffensen.<br />

lso.co.uk<br />

City of <strong>London</strong> Festival<br />

The City is alive with culture this summer and the LSO is delighted<br />

to be taking part in a highlight of the City’s cultural calendar: the<br />

50th anniversary of the City of <strong>London</strong> Festival (24 <strong>June</strong> to 27 July).<br />

The LSO’s contribution comes in the form of two performances<br />

of Berlioz’s Requiem at St Paul’s Cathedral under Sir Colin Davis<br />

(Monday 25 and Tuesday 26 <strong>June</strong>). In addition, there is also an<br />

independent four-day Celebrate the City event, Four Days in the<br />

Square Mile from 21 to 24 <strong>June</strong>.<br />

colf.org and visitthecity.co.uk/culture<strong>2012</strong><br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

As part of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>2012</strong> celebrations, the LSO will also perform<br />

in three special concerts in association with the Barbican, the first<br />

with South American singer-songwriter Gilberto Gil and conductor<br />

François-Xavier Roth (4 July), then on 21 July award-winning composer<br />

and producer Nitin Sawhney will conduct the <strong>Orchestra</strong> in his newly<br />

written score for Hitchcock’s film The Lodger, and finally on 25 and<br />

26 July jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis joins Sir Simon Rattle and the<br />

LSO with Jazz at Lincoln Center <strong>Orchestra</strong> for two concerts featuring<br />

the UK premiere of Marsalis’ Swing <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

lso.co.uk/whatson<br />

2 Welcome & News Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik

Henry Purcell (1659–95) arr Benjamin Britten<br />

Chacony in G minor (date unknown)<br />

‘Chacony’ is an idiosyncratic English spelling of the French<br />

‘Chaconne’, the term applied to a triple-time dance movement in<br />

which a short bass-line theme or chord progression is repeated a<br />

number of times while other instruments or voices spin variations<br />

over the top. The practice – whether applied to a ‘ciacona’ or other<br />

popular basses such as the bergamasca or a follia – had its origins<br />

in improvised dance music, but found its way into many genres<br />

of instrumental music during the 16th and 17th centuries, from<br />

Elizabethan keyboard pieces to Italian violin sonatas, to the orchestral<br />

chaconnes which traditionally appeared towards the end of French<br />

operas. This last is perhaps the most pertinent model for a piece like<br />

Purcell’s G minor Chacony for three (probably solo) violins and basso<br />

continuo, though it is not known exactly when and why he composed it.<br />

Purcell’s own assessment of composing ‘upon a ground’ (as the<br />

English called it) was that it was ‘a very easie thing to do, and requires<br />

but little Judgement’, but that rather belies the evidence of such well-<br />

known examples as ‘Dido’s Lament’ from the opera Dido and Aeneas<br />

or the song ‘Music for a while’ that he was a master of the genre,<br />

able to balance with perfect naturalness the competing demands<br />

of variational freedom and repetitive continuity. Yet the Chacony is<br />

more than just an exercise in craftsmanship; with its elegant minor-<br />

key melancholy and typically rich Purcellian inner part-writing, it is a<br />

powerfully affecting snapshot of its composer’s artistic personality.<br />

Benjamin Britten, one of the 20th century’s most influential lovers of<br />

Purcell, admired it for its ‘mixture of clarity, brilliance, tenderness and<br />

strangeness’ and made his sympathetic realisation of it for modern<br />

string orchestra in 1948.<br />

Programme Note © Lindsay Kemp<br />

Lindsay Kemp is a senior producer for BBC Radio 3, Artistic Director<br />

of the Lufthansa Festival of Baroque Music, and a regular contributor<br />

to Gramophone magazine.<br />

Henry Purcell (1659–95)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Henry Purcell was born, married, fathered six children of whom only<br />

two made it past infancy, and died just a stone’s throw away from<br />

Westminster Abbey.<br />

Following his father’s death in 1664, Purcell was placed in the care of<br />

his uncle, Thomas Purcell, who was a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal<br />

where Purcell duly became a chorister until his voice broke in 1673.<br />

Purcell received tuition from John Blow, who later passed on his office<br />

as organist of Westminster Abbey to Purcell in 1679, a position which<br />

Purcell also held in conjunction with being organist at the Chapel Royal<br />

from 1682. Purcell is thought to have been composing from just nine<br />

years of age but his earliest certified work was an ode for the King’s<br />

birthday in 1670. Purcell quickly developed a reputation for his choral<br />

works, most notably the anthems I was glad and My heart is inditing<br />

for the coronation of James II in 1685 and Come ye Sons of Art, a<br />

gloriously elaborate birthday ode for Queen Mary. Purcell’s Te Deum<br />

and Jubilate Deo were written for St Cecilia’s Day in 1693 and was the<br />

first English Te Deum ever composed with orchestral accompaniment.<br />

Purcell also had a long-standing association with the theatre,<br />

composing music for The Fairy-Queen (an adaptation of Shakespeare’s<br />

A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and by far his most famous dramatic<br />

output, Dido and Aeneas, as well as incidental music for Shakespeare’s<br />

The Tempest and Robert Howard’s The Indian Queen, for which<br />

Purcell’s younger brother Daniel completed much of the music for<br />

the final act after Purcell’s death.<br />

Purcell died a successful and wealthy, albeit young, man in 1695.<br />

Many theories have circulated around the circumstances of his death<br />

but the most prevalent are that he either caught a chill after finding<br />

himself locked out of the house by his wife or that he contracted<br />

tuberculosis. Purcell was buried adjacent to the organ in Westminster<br />

Abbey where his epitaph reads, ‘Here lyes Henry Purcell Esq, who left<br />

this life and is gone to that blessed place where only his harmony can<br />

be exceeded’.<br />

Programme Notes<br />

3

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91)<br />

Piano Concerto No 20 in D minor, K466 (1785)<br />

1 Allegro<br />

2 Romance<br />

3 Rondo: Allegro assai<br />

Maria João Pires piano<br />

The decade which Mozart spent in Vienna from 1781 until his death<br />

was when he truly found his own voice as a composer, and nowhere<br />

is this new maturity and individuality better shown than in his piano<br />

concertos of the period. Altogether he wrote 17 of them while in the<br />

Imperial capital, mostly for himself to play at the public and private<br />

concerts which helped provide him with financial support, and as such<br />

they were the works with which he was most closely associated by his<br />

audiences. More importantly, it was with them that he established the<br />

piano concerto for the first time as a sophisticated means of personal<br />

expression rather than a vehicle for polite public display.<br />

The high-point in the series came with the five concertos composed<br />

in the period of just over a year from the beginning of 1785. K466 –<br />

completed and first performed in February 1785 – is chronologically<br />

at the head of this group, but musically speaking it also stands out<br />

in many ways. The composer’s father Leopold, visiting Vienna at the<br />

time, heard the premiere, and a little over a year later was organising<br />

a performance by a local pianist back in Salzburg. He later described<br />

the occasion in a letter to his daughter: ‘Marchand played it from<br />

the score, and [Michael, brother of Joseph] Haydn turned over the<br />

pages for him, and at the same time had the pleasure of seeing with<br />

what art it is composed, how delightfully the parts are interwoven<br />

and what a difficult concerto it is. We rehearsed it in the morning and<br />

had to practise the rondo three times before the orchestra could<br />

manage it’. One can well imagine the impression the piece made in<br />

the composer’s home town; there can be few clearer demonstrations<br />

of how far he had left Salzburg behind. D minor is a relatively unusual<br />

key for Mozart, and therefore a significant one. Later he would use it<br />

both for Don Giovanni’s damnation scene and for the Requiem, and<br />

there is something of the same grim familiarity with the dark side,<br />

a glimpse of the grave it seems, in the first movement of this concerto.<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

The opening orchestral section contrasts brooding menace with<br />

outbursts of passion, presenting along the way most of the melodic<br />

material that will serve the rest of the movement. Even so, it is with a<br />

new theme, lyrical but searching and restless, that the piano enters;<br />

this is quickly brushed aside by the orchestra, but the soloist does not<br />

give it up easily, later using it to lead the orchestra through several<br />

different keys in the central development section. The movement<br />

ends sombrely, pianissimo.<br />

The slow second movement, in B-flat major, is entitled ‘Romance’,<br />

a vague term used in Mozart’s day to suggest something of a song-<br />

like quality. In fact this is a rondo, in which three appearances of the<br />

soloist’s artless opening theme are separated by differing episodes,<br />

the first a drawn-out melody for the piano floating aristocratically<br />

over gently throbbing support from the strings, and the second a<br />

stormy minor-key eruption of piano triplets, shadowed all the way by<br />

sustained woodwind chords. Storminess returns in the finale, though<br />

this time one senses that it is of a more theatrical kind than in the<br />

first movement. This is another rondo, and although the main theme<br />

is fiery and angular, much happens in the course of the movement to<br />

lighten the mood, culminating after the cadenza in a turn to D major<br />

for the concerto’s final pages. A purely conventional ‘happy ending’<br />

to send the audience away smiling? Perhaps so, but the gentle<br />

debunking indulged in by the horns and trumpets just before the end<br />

suggests that Mozart knew precisely what he was doing.<br />

Programme Note © Lindsay Kemp<br />

Music’s better shared!<br />

The LSO offers great benefits for groups of <strong>10</strong>+ including 20% off<br />

standard ticket prices, priority booking, free interval hot drinks and,<br />

for bigger groups, the chance of a private interval reception.<br />

To reserve tickets, call the dedicated Group Booking line on<br />

020 7382 7211. If you have general queries, please call LSO Groups<br />

Rep Fabienne Morris on 020 7382 2522. Tonight we welcome:<br />

Shirley Arber & Friends, Classical Partners, Farnham U3a<br />

Concert Club, Faversham Music Club, Dan Petersen &<br />

Friends, Redbridge & District U3a and Frances Sell & Friends

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Born in Salzburg on 27 January 1756, Mozart began to pick out<br />

tunes on his father’s keyboard before his fourth birthday. His first<br />

compositions, an Andante and Allegro for keyboard, were written<br />

down in the early months of 1761; later that year, the boy performed<br />

in public for the first time at the University of Salzburg. Mozart’s<br />

ambitious father, Leopold, court composer and Vice-Kapellmeister<br />

to the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, recognised the money-making<br />

potential of his precocious son and pupil, embarking on a series of<br />

tours to the major courts and capital cities of Europe.<br />

In 1777 Wolfgang, now 21 and frustrated with life as a musician-in-<br />

service at Salzburg, left home, visiting the court at Mannheim on<br />

the way to Paris. The Parisian public gave the former child prodigy a<br />

lukewarm reception, and he struggled to make money by teaching<br />

and composing new pieces for wealthy patrons. A failed love affair<br />

and the death of his mother prompted Mozart to return to Salzburg,<br />

where he accepted the post of Court and Cathedral Organist.<br />

In 1780 he was commissioned to write an opera, Idomeneo, for the<br />

Bavarian court in Munich, where he was treated with great respect.<br />

The servility demanded by his Salzburg employer finally provoked<br />

Mozart to resign in 1781 and move to Vienna in search of a more<br />

suitable position, fame and fortune. In the last decade of his life, he<br />

produced a series of masterpieces in all the principal genres of music,<br />

including the operas The Marriage of Figaro (1785), Don Giovanni<br />

(1787), Così fan tutte and The Magic Flute, the Symphonies Nos 40<br />

and 41 (‘Jupiter’), a series of piano concertos, a clarinet quintet and<br />

the Requiem, left incomplete at his death on 5 December 1791.<br />

Composer Profile © Andrew Stewart<br />

INTERVAL: 20 minutes<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Bernard Haitink & Maria João Pires<br />

this season and next with the LSO<br />

Thu 14 Jun <strong>2012</strong><br />

Purcell arr Steven Stucky<br />

Funeral Music for Queen Mary<br />

Mozart Piano Concerto No 23<br />

Bruckner <strong>Symphony</strong> No 7<br />

Bernard Haitink conductor<br />

Maria João Pires piano<br />

Supported by LSO Patrons<br />

Box Office<br />

020 7638 8891 (bkg fee)<br />

lso.co.uk (reduced bkg fee)<br />

Tue 12 Feb 2013<br />

Britten Four Sea Interludes<br />

Mozart Piano Concerto No 21<br />

Beethoven <strong>Symphony</strong> No 7<br />

Bernard Haitink conductor<br />

Maria João Pires piano<br />

Sun 17 & Thu 21 Feb 2013<br />

Mozart Piano Concerto No 17<br />

Bruckner <strong>Symphony</strong> No 9<br />

Bernard Haitink conductor<br />

Maria João Pires piano<br />

21 Feb supported by LSO Premier<br />

Programme Notes<br />

5

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 9 in C major (‘The Great’) D944 (1825, rev 1826)<br />

1 Andante – Allegro ma non troppo<br />

2 Andante con moto<br />

3 Scherzo: Allegro vivace<br />

4 Finale: Allegro vivace<br />

It is not clear when people first began referring to Schubert’s last<br />

completed symphony as the ‘Great C major’. Apparently the tag was<br />

first applied to differentiate it from the ‘little’ C major symphony,<br />

known as ‘No 6’, which Schubert wrote in 1817–18. But the nickname<br />

is well deserved: apart from Mozart’s ‘Jupiter’ it is the great <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

in C. Not only is it conceived on a huge scale, its sophistication and<br />

formal mastery are as impressive as its vitality, imaginative range and<br />

the infectious memorability of its main themes.<br />

That mastery is all the more impressive when one considers that it<br />

was only the year before he began work on the score that Schubert<br />

had declared his intention in a letter ‘to pave my way to grand<br />

symphony’. That same year, 1824, Schubert had also heard the<br />

premiere of Beethoven’s ‘Choral’ Ninth – a big influence to digest,<br />

one might have thought, and yet Schubert’s response to that<br />

challenge is confident and utterly original. Indeed Schubert clearly<br />

felt so sure of himself that he was able to invoke Beethoven’s Ninth<br />

without fear of comparison: the woodwind figures at the beginning of<br />

the development section of Schubert’s finale contain an unmistakable<br />

reference to a phrase from Beethoven’s famous ‘Ode to Joy’ theme.<br />

Almost certainly the C major <strong>Symphony</strong>’s vigour and assurance reflect<br />

something of Schubert’s mood in the summer of 1825, when he made<br />

a long walking tour with friends in Upper Austria. At one point in that<br />

extended holiday the party stayed at the house of Anton Ottenwalt,<br />

brother-in-law of Schubert’s close friend Josef von Spaun. Ottenwalt<br />

wrote that ‘Schubert looks so well and strong, is so bright and relaxed,<br />

so genial and communicative, that one cannot but be sincerely<br />

delighted’. In the next sentence, Ottenwalt reports that Schubert<br />

‘had been working on a symphony … which is to be performed in<br />

Vienna this winter’. For Ottenwalt there was clearly a connection<br />

between Schubert’s state of mind and his current musical fertility.<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

But one could go further than that. The symphony is dominated<br />

by images of physical movement: the muscular, striding theme of<br />

the first movement; the exuberant waltz-tunes of the Scherzo; the<br />

hurtling vitality of the Finale – even the ‘slow’ second movement<br />

is carried forward by a march-like tread, introduced on the strings<br />

before the oboe sounds the leading melody. It is hard to imagine a<br />

greater contrast with the lyrical, introverted character of the B minor<br />

‘Unfinished’ <strong>Symphony</strong>, composed in much less happy times three<br />

years earlier. It is surely also significant that that productive summer<br />

of 1825 saw the completion of one of Schubert’s most awe-inspiring<br />

songs, a hymn to the God revealed in nature entitled ‘Die Allmacht’<br />

(Omnipotence) – also in C major and, like the finale of the new<br />

symphony, dominated by repeated triplet rhythms. An invigorating<br />

walking regime, a delight in nature, thoughts of God inspired by sublime<br />

landscapes – all of this is implicit in the ‘Great’ C major <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

Despite his excellent spirits and abundant inspiration, Schubert had to<br />

wrestle with the symphony before it arrived at its final form. The score<br />

was extensively revised in 1826, as a result of which it became even<br />

longer than that already ambitious first version. Finally the symphony<br />

was handed over to the Vienna Philharmonic Society; parts were<br />

duly copied, and at some time towards the end of 1826 there was a<br />

run-through by the orchestra. But the hoped-for public performance<br />

did not materialise. According to one account, the symphony was<br />

‘provisionally put aside, because of its length and difficulty’. Schubert<br />

was never to hear the work performed in concert. It wasn’t until March<br />

1839 – eleven years after the composer’s death – that Mendelssohn<br />

conducted it at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. And despite enthusiastic<br />

championship, especially by the composer Robert Schumann –<br />

who made a point of praising its ‘heavenly length’ – it was not widely<br />

recognised as the masterpiece it is until much later. Even well into<br />

the 20th century it was not uncommon for the symphony to be<br />

performed with cuts.<br />

It is obvious from the opening bars that this is to be a symphonic<br />

journey on a grand scale. Two horns, unaccompanied, announce a<br />

quietly majestic tune that is to find echo in many of the symphony’s<br />

later ideas. Instead of providing a conventional classical ‘slow

introduction’ the substantial Andante first section is more in the<br />

nature of a set of free variations on the horns’ melody, building<br />

steadily to a powerful full-orchestral climax, at which the main Allegro<br />

ma non troppo theme (clearly alluding to the horns’ final phrase)<br />

sweeps in. Later, after the gentler second theme (woodwinds),<br />

trombones take another phrase from the horn melody and develop it<br />

in a thrilling long crescendo – one of the passages Schubert added in<br />

his revision of 1826. The first movement concludes with two impressive<br />

restatements of the horn tune in a new, condensed form: the journey<br />

has come full circle, but the perspective has changed radically.<br />

The following Andante con moto leads off at a walking pace – the<br />

kind of measured, almost hypnotic tread one encounters in several<br />

of Schubert’s later songs and chamber works. There are stiller,<br />

reflective, mysterious passages, but it is the march movement that<br />

provokes the movement’s astonishing climax: a huge fff (extremely<br />

loud) dissonance followed by an awe-struck silence – not everything<br />

in this symphony is joyous or good-humoured. The Scherzo is an<br />

elemental symphonic waltz: Schubert was clearly impressed by the<br />

scale of the scherzo of Beethoven’s Ninth, but responded with a<br />

kind of movement that is entirely personal – at no point inhibited by<br />

Beethoven’s gigantic shadow.<br />

For sustained drive and soaring intensity the Finale is unparalleled.<br />

The writer Donald Francis Tovey described the second theme as having<br />

‘the momentum of a planet in its orbit’, but the description could<br />

just as well apply to the movement as a whole. The final crescendo<br />

is electrifying, culminating in massive pounding unison Cs – perhaps<br />

Schubert was thinking of the statue of the Commendatore knocking at<br />

the door in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Whatever the case, it adds a note<br />

of ambiguity to the symphony’s final pages. Joy or terror? As so often<br />

in the later Schubert, the exhilaration also leaves room for doubt.<br />

Programme Note © Stephen Johnson<br />

Stephen Johnson is the author of Bruckner Remembered (Faber). He<br />

also contributes regularly to the BBC Music Magazine, and broadcasts<br />

for BBC Radio 3 (Discovering Music), Radio 4 and the World Service.<br />

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

In childhood, Schubert was taught violin by his schoolmaster father<br />

and piano by his eldest brother. He rapidly became more proficient<br />

than his teachers, and showed considerable musical talent, so<br />

much so that in 1808 he became a member of Vienna’s famous<br />

Imperial Court chapel choir. He was educated at the Imperial City<br />

College, where he received lessons from the composer Salieri. His<br />

father, eager that Franz should qualify as a teacher and work in the<br />

family’s schoolhouse, encouraged the boy to return home in 1814.<br />

Compositions soon began to flow, although teaching duties interrupted<br />

progress. Despite his daily classroom routine, Schubert managed<br />

to compose 145 songs in 1815, together with four stage works, two<br />

symphonies, two Masses and a large number of chamber pieces.<br />

Though the quantity of Schubert’s output is astonishing enough,<br />

it is the quality of his melodic invention and the richness of his<br />

harmonic conception that are the most remarkable features of his<br />

work. He was able to convey dramatic images and deal with powerful<br />

emotions within the space of a few bars, as he so often did in his<br />

songs and chamber works. The public failure of his stage works<br />

and the reactionary attitudes to his music of conservative Viennese<br />

critics did not restrict his creativity, nor his enjoyment of composition;<br />

illness, however, did affect his work and outlook. In 1824 Schubert<br />

was admitted to Vienna’s General Hospital for treatment for syphilis.<br />

Although his condition improved, he suffered side-effects from his<br />

medication, including severe depression. During the final four years<br />

of his life, Schubert’s health declined; meanwhile, he created some<br />

of his finest compositions, chief among which are the song-cycles<br />

Winterreise and Schwanengesang, and the last piano sonatas.<br />

Composer Profile © Andrew Stewart<br />

Programme Notes<br />

7

Bernard Haitink<br />

Conductor<br />

‘On a night such as this,<br />

the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> seems to be<br />

a confederacy of virtuosos’<br />

The Evening Standard on Haitink and the LSO<br />

With an international conducting career<br />

that has spanned more than five and a half<br />

decades, Amsterdam-born Bernard Haitink is<br />

one of today’s most celebrated conductors.<br />

Bernard Haitink was Chief Conductor of the<br />

Royal Concertgebouw <strong>Orchestra</strong> for 27 years<br />

and is now their Conductor Laureate. In<br />

addition, Haitink has previously held posts<br />

as Music Director of the Royal Opera, Covent<br />

Garden, Glyndebourne Festival Opera,<br />

the Dresden Staatskapelle, and Principal<br />

Conductor of the Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and the <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic.<br />

He is Conductor Emeritus of the Boston<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>. He has made frequent<br />

guest appearances with most of the world’s<br />

leading orchestras.<br />

Bernard Haitink began the 2011/12 season<br />

with the Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and<br />

the New York Philharmonic, to which he<br />

returned for the first time in over 30 years.<br />

February <strong>2012</strong> saw the conclusion of a<br />

Beethoven Cycle with the Chamber <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

of Europe in the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam,<br />

and the Salle Pleyel, Paris. Other highlights of<br />

2011/12 included the Christmas Day concert<br />

with the Royal Concertgebouw <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

and engagements with the symphony<br />

orchestra of the Bayerischer Rundfunk and<br />

the Tonhalle <strong>Orchestra</strong>, as well as a three<br />

week residency with the Boston <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

Haitink brings the season to a close with<br />

concerts in <strong>London</strong> and Paris with the <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>, and in the Proms,<br />

Salzburg and Lucerne Festivals with the<br />

Vienna Philharmonic.<br />

Bernard Haitink has recorded widely for Phillips,<br />

Decca and EMI with the Concertgebouw<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic<br />

orchestras and the Boston <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

His discography also includes many opera<br />

recordings with the Royal Opera, Glyndebourne,<br />

the Bavarian Radio <strong>Orchestra</strong> and Dresden<br />

Staatskapelle. Most recently he has recorded<br />

extensively with the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> for LSO Live, including the complete<br />

Brahms and Beethoven symphonies, and with<br />

the Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong> on their Resound<br />

label. Haitink’s recording of Janáček s Jenu˚ fa<br />

with the Royal Opera received a Grammy Award<br />

for best opera recording in 2004, and his<br />

Shostakovich <strong>Symphony</strong> No 4 recording with<br />

the Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong> was awarded a Grammy<br />

for Best <strong>Orchestra</strong>l Performance of 2008.<br />

Bernard Haitink has received many<br />

international awards in recognition of his<br />

services to music, including both an honorary<br />

Knighthood and the Companion of Honour in<br />

the United Kingdom, and the House Order of<br />

Orange-Nassau in the Netherlands. He was<br />

named Musical America’s Musician of the<br />

Year for 2007.<br />

8 The Artists Bernard Haitink © Clive Barda

Maria João Pires<br />

Piano<br />

‘Pires doesn’t pull phrases<br />

about yet her playing has<br />

infinite flexibility ... there was<br />

a real sense of conversation’<br />

The Evening Standard on Pires and the LSO<br />

One of the finest musicians of her generation,<br />

Maria João Pires continues to transfix<br />

audiences with the spotless integrity,<br />

eloquence, and vitality of her art.<br />

She was born on 23 July 1944 in Lisbon and<br />

gave her first public performance in 1948.<br />

In Portugal she studied with Campos Coelho<br />

and Francine Benoit, later continuing her studies<br />

in Germany with Rosl Schmid and Karl Engel.<br />

Since 1970 she has dedicated herself to<br />

reflecting on the influence of art on life,<br />

community and education, and in trying<br />

to develop new ways of implementing<br />

pedagogic theories within society. In the last<br />

<strong>10</strong> years she has held many workshops with<br />

students from all round the world, and has<br />

taken her philosophy and teaching to Japan,<br />

Maria João Pires © Felix Broede<br />

Brazil, Portugal, France, and Switzerland. In<br />

2005 she formed an experimental theatre,<br />

dance and music group, Art Impressions,<br />

and together they have produced two major<br />

projects – Transmissions and Schubertiade.<br />

In <strong>2012</strong>, in addition to her chamber music<br />

recitals with the Brazilian cellist Antonio<br />

Meneses, she appears with all the major<br />

European orchestras under the batons<br />

of Bernard Haitink, Claudio Abbado and<br />

Riccardo Chailly, among others. A frequent<br />

visitor to Japan she returns there in spring<br />

2013 with the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

and Haitink.<br />

Maria João Pires recorded with Erato for<br />

15 years and subsequently, for the last 24<br />

years, with Deutsche Grammophon. Her<br />

large and varied discography covers solo<br />

repertoire, chamber music and concertos.<br />

Her latest recording, of two Mozart concertos<br />

conducted by Claudio Abbado, will be<br />

released in autumn <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

LSO Season 2011/12<br />

Gianandrea Noseda<br />

Beethoven <strong>Symphony</strong> No 5<br />

Thu 21 Jun 7.30pm<br />

Beethoven <strong>Symphony</strong> No 5<br />

Wagner Prelude and Liebestod<br />

from ‘Tristan und Isolde’<br />

Berg Three Fragments from ‘Wozzeck’<br />

Gianandrea Noseda conductor<br />

Angela Denoke soprano<br />

Sponsored by BAT<br />

Recommended by Classic FM<br />

Tickets from £<strong>10</strong><br />

Box Office 020 7638 8891<br />

lso.co.uk<br />

The Artists<br />

9

Sir Colin Davis in <strong>2012</strong>/13<br />

Last few tickets left!<br />

Thu 27 Sep <strong>2012</strong> 7.30pm<br />

85th Birthday Concert<br />

with pianists Radu Lupu and Mitsuko Uchida<br />

Thu 18 Oct <strong>2012</strong> 7.30pm<br />

Beethoven and Elgar<br />

with pianist Simon Trpčeski<br />

Wed 5 Dec <strong>2012</strong> 7.30pm<br />

Queen’s Medal for Music Gala<br />

with violinist Maxim Vengerov<br />

Returns only<br />

Sun 13 Jan 2013 7.30pm<br />

Mozart Requiem<br />

with the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Chorus<br />

Season <strong>2012</strong>/13<br />

Other Best-sellers<br />

Thu 8 Nov <strong>2012</strong> 7.30pm<br />

Music for the Big Screen:<br />

The Best of John Williams<br />

with conductor Frank Strobel<br />

12 Feb 2013 7.30pm<br />

Mozart, Bruckner and Beethoven<br />

with Bernard Haitink and Maria João Pires<br />

Wed 22 May 2013 7.30pm<br />

Valery Gergiev<br />

60th Birthday Gala Concert<br />

with violinist Leonidas Kavakos<br />

Sun 9 Jun 2013 7.30pm<br />

Michael Tilson Thomas<br />

conducts Britten and Shostakovich<br />

with cellist Yo-Yo Ma<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Tickets from £<strong>10</strong><br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

lso.co.uk<br />

020 7638 8891

On stage<br />

First Violins<br />

Roman Simovic Leader<br />

Tomo Keller<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Elizabeth Pigram<br />

Laurent Quenelle<br />

Harriet Rayfield<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Ian Rhodes<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

David Worswick<br />

Second Violins<br />

Evgeny Grach<br />

Thomas Norris<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

Miya Vaisanen<br />

Matthew Gardner<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Andrew Pollock<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Raja Halder<br />

Hazel Mulligan<br />

Violas<br />

Edward Vanderspar<br />

Gillianne Haddow<br />

Malcolm Johnston<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Lander Echevarria<br />

Anna Green<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Heather Wallington<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Cellos<br />

Timothy Hugh<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Minat Lyons<br />

Amanda Truelove<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Colin Paris<br />

Nicholas Worters<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Thomas Goodman<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Flutes<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Siobhan Grealy<br />

Oboes<br />

Christopher Cowie<br />

Michael O’Donnell<br />

Clarinets<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bassoons<br />

Rachel Gough<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Horns<br />

Timothy Jones<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Geremia Iezzi<br />

David McQueen<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philip Cobb<br />

Roderick Franks<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

James Maynard<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players.<br />

The Scheme is supported by:<br />

The Barbers’ Company<br />

The Carpenters’ Company<br />

Charles and Pascale Clark<br />

Fidelio Charitable Trust<br />

The Ironmongers’ Company<br />

Robert and Margaret Lefever<br />

LSO Friends<br />

Musicians Benevolent Fund<br />

The Polonsky Foundation<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor<br />

Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Photography<br />

Mark Harrison, Kevin Leighton,<br />

Bill Robinson, Alberto Venzago,<br />

Nigel Wilkinson<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450<br />

The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

11

Inbox<br />

Your thoughts and comments about recent performances<br />

‘Surprise and inspire’<br />

Selena Lemalu<br />

This programme was like taking<br />

a guided tour of a beautifully<br />

curated exhibition of an iconic<br />

figure’s work but from an<br />

unusual perspective. Instead<br />

of wandering from room to<br />

room taking in images, rich<br />

soundscapes materialised in<br />

the space before us, through<br />

the artistry of the LSO chamber<br />

ensemble. Most exciting to get an<br />

insight into Stravinsky’s creative<br />

process and his influence on the<br />

development of jazz music.<br />

Truly an evening that did ‘surprise<br />

and inspire’.<br />

LSO Chamber <strong>Orchestra</strong> /<br />

Stravinsky Festival,<br />

LSO St Luke’s 17 May<br />

12 Inbox<br />

‘Great stuff LSO’<br />

David Valentine<br />

Sir Colin does it again!<br />

A wonderful night at the<br />

Barbican, an amazing, rarely<br />

heard work, with a superb cast,<br />

choir and orchestra. Lars Woldt’s<br />

performance at short notice was<br />

memorable. Great stuff LSO.<br />

Weber’s Der Freischütz<br />

with Sir Colin Davis<br />

Barbican, 19 & 21 April<br />

Katie Bishop<br />

Hey guys! Have been lucky<br />

enough to see you a few times<br />

and just wanted to thank you for<br />

being so fantastic and bringing<br />

music and life into our hearts!<br />

Bachtrack<br />

Fabulous concert last night at<br />

Barbican from <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>. Stravinsky’s L’Histoire<br />

du Soldat [The Soldier’s Tale]<br />

was wonderful and so fresh and<br />

modern sounding. We noted<br />

Simon Callow’s scrutiny of the<br />

score and enjoyment of the<br />

music as well as giving a riveting<br />

performance!<br />

Barbican, 13 May<br />

facebook.com/<br />

londonsymphonyorchestra<br />

Send us your thoughts on<br />

tonight’s concert<br />

Using a smartphone QR code reader,<br />

scan this barcode to go to our reviews page,<br />

email comment@lso.co.uk, or go to our<br />

facebook or twitter pages<br />

Nathan Madsen<br />

People, the @londonsymphony’s<br />

‘learn the Rite of Spring’s<br />

rhythms’ campaign is <strong>10</strong>0,000<br />

tons of AWESOME.<br />

The Rite of Spring clapping<br />

video made for Trafalgar Square<br />

concert, 12 May<br />

Mike Hill<br />

@londonsymphony Enjoyed<br />

Oedipus Rex – not a work I<br />

knew. Nice that @simonhalsey<br />

got a rousing cheer at the end.<br />

Great evening.<br />

Barbican, 15 May<br />

Chamber <strong>Orchestra</strong> of Europe<br />

@londonsymphony Loved the<br />

Gergiev Rite! Amazing. What a<br />

guy and what a band. Bravo all!<br />

twitter.com/londonsymphony<br />

Please note that the LSO may edit your comments and not all emails will be published.