Sunday 30 October 2011 - London Symphony Orchestra

Sunday 30 October 2011 - London Symphony Orchestra

Sunday 30 October 2011 - London Symphony Orchestra

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

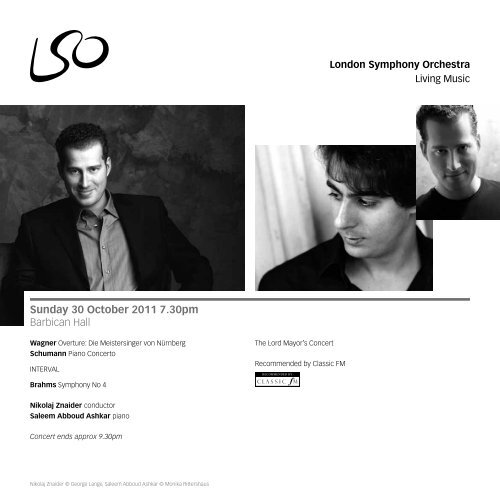

<strong>Sunday</strong> <strong>30</strong> <strong>October</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Wagner Overture: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg<br />

Schumann Piano Concerto<br />

INteRvAL<br />

Brahms <strong>Symphony</strong> No 4<br />

Nikolaj Znaider conductor<br />

Saleem Abboud Ashkar piano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Nikolaj Znaider © George Lange, Saleem Abboud Ashkar © Monika Rittershaus<br />

the Lord Mayor’s Concert<br />

Recommended by Classic FM<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music

Welcome News<br />

Welcome to this evening’s concert at the Barbican. It is a delight<br />

to welcome Nikolaj Znaider to conduct the LSO for the first time in<br />

<strong>London</strong>, following a highly successful conducting debut with the<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> in Bucharest in September. He will be joined this evening<br />

by pianist Saleem Abboud Ashkar, also making his LSO debut.<br />

Nikolaj will join us again later this season, as soloist, to play<br />

Bartók’s violin Concerto No 2 on 8 May 2012.<br />

this evening, the LSO is joined by Lord Mayor, Alderman Michael<br />

Bear, and members of the Common Council of the City of <strong>London</strong><br />

Corporation. the LSO is deeply grateful for their continued support.<br />

I would also like to take the opportunity to thank our media partner<br />

Classic FM for continuing to be a strong advocate of the LSO.<br />

I hope you enjoy the concert and that you can join us for our<br />

next two performances which form part of a weekend-long<br />

celebration of French heroine Joan of Arc’s 600th birthday with<br />

conductor Marin Alsop.<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

LSO Backstage Pass – for our teenage audiences<br />

If you’re aged 12–18, join our free ‘LSO Backstage Pass’ teens<br />

scheme and take advantage of cheap tickets, pre-concert events<br />

and exclusive chances to meet the LSO players. Before tonight’s<br />

concert there was a free talk introducing this evening’s music and<br />

what it’s like to play in the <strong>Orchestra</strong>, plus a sneak peak backstage.<br />

Find out more at lso.co.uk/backstagepass<br />

The LSO’s <strong>2011</strong> New York tour<br />

earlier this month the <strong>Orchestra</strong> took up a week-long residency in<br />

New York’s Lincoln Center. Under the baton of Sir Colin Davis,<br />

Nikolaj Znaider performed Sibelius’ violin Concerto on 19 <strong>October</strong>,<br />

and on 21 <strong>October</strong> Sir Colin Davis led the <strong>Orchestra</strong> in Beethoven’s<br />

Missa Solemnis with the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Chorus.<br />

Finally, on <strong>Sunday</strong> 23 <strong>October</strong>, Gianandrea Noseda conducted<br />

Britten’s War Requiem with soloists Ian Bostridge and Simon<br />

Keenlyside in the wake of rave reviews for their <strong>London</strong> performances<br />

at the Barbican. LSO Principal Flute Gareth Davies has been closely<br />

following the progress of the tour in his blog.<br />

lsoontour.wordpress.com<br />

Nikolaj Znaider and Sir Colin Davis in conversation<br />

at LSO St Luke’s, Monday 31 <strong>October</strong> 11am<br />

tomorrow morning at LSO St Luke’s, Nikolaj Znaider will be in<br />

conversation with his conducting mentor, Sir Colin Davis,<br />

sharing their experiences of working on stage as part of<br />

Centre for <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

Watch live and submit your questions online at<br />

facebook.com/londonsymphonyorchestra<br />

2 Welcome & News Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik

Richard Wagner (1813–1883)<br />

Overture: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868)<br />

First performed in Munich in 1868, Die Meistersinger von Nürmberg<br />

is Wagner’s only mature comedy; it is also a vast and – dramatically<br />

and musically – a super-enriched work and indeed one of the longest<br />

operas ever composed. It was a success from the first, and continues<br />

to hold a regular place in the repertory, even if its association with<br />

German Nationalism at various points has besmirched its reputation.<br />

Despite that, in its wisdom and rich humanity of characterisation<br />

it can provide one of the most life-affirming experiences the<br />

theatre has to offer.<br />

Unusually for Wagner, the action takes place in a specific period<br />

and location: the German city of Nuremberg in the mid-16th century.<br />

there prospers the guild of Mastersingers, its members local artisans<br />

and merchants who create art – specifically songs – as a central<br />

activity of their lives and according to strict, time-honoured rules.<br />

Into this intensely traditional community bursts the unruly knight<br />

Walther von Stolzing, who wants to win the hand of eva as the<br />

prize in a forthcoming singing contest. Supported by the local<br />

cobbler-poet Hans Sachs (one of the opera’s genuine historical<br />

figures), but opposed by the pernickety town-clerk Beckmesser,<br />

in the final scene Walther is able to defeat his rival with his inspired<br />

‘Prize Song’ and thus claim his bride.<br />

Wagner first drafted the scenario in 1845, though it was not until<br />

Tristan und Isolde was finished that he began to set Act One to<br />

music in 1863; the whole opera was completed four years later.<br />

Yet, amazingly, so sure was he of its musical content that he had<br />

already composed the overture and conducted its premiere in 1862.<br />

Its main themes represent the Mastersingers and their cheeky young<br />

apprentices, as well as Walther’s ‘Prize Song’, with Wagner bringing<br />

them all together at the close in a stunning display of counterpoint.<br />

Programme Note © George Hall<br />

George Hall writes widely on classical music, including for<br />

The Guardian, BBC Music Magazine and Opera.<br />

Richard Wagner<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Richard Wagner was born on 22 May 1813 in Leipzig. His musical<br />

talent was encouraged at Leipzig’s Nicolaischule and through<br />

lessons with Christian Gottlieb Müller. In 1829 he completed his first<br />

instrumental compositions, enrolling briefly as a music student at<br />

Leipzig University two years later. Wagner married the actress Minna<br />

Planer in November 1836, the couple moving from Riga to Paris<br />

in 1839 to escape Wagner’s creditors and living there in extreme<br />

poverty. Here he completed Rienzi and created The Flying Dutchman.<br />

Rienzi proved a big success at its Dresden premiere in <strong>October</strong> 1842,<br />

establishing Wagner’s reputation.<br />

In the 1850s, he began composing his monumental cycle of four<br />

Nibelung operas, also completing his ground-breaking opera<br />

Tristan und Isolde. His financial difficulties were removed in 1864<br />

by the teenage King Ludwig II, a dedicated Wagnerite who<br />

commissioned Der Ring des Nibelungen. Wagner’s comic masterpiece,<br />

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg was premiered on Ludwig’s<br />

command; the King later funded the building of a new theatre at<br />

Bayreuth for the sole performance of Wagner’s works.<br />

For the remaining years of his life, Wagner worked on establishing<br />

the Bayreuth Festival and composing Parsifal, written specifically for<br />

Bayreuth. He died in venice on 13 February 1883, suffering a heart<br />

attack after an impassioned row with his second wife, Cosima.<br />

According to Wagnerian legend, there has been more written about<br />

the composer than anybody other than Napoleon and Jesus Christ.<br />

Although the claim is inaccurate, it is typical of the myths that have<br />

become attached to Wagner’s life and works. the vast scale of his<br />

creative output, its revolutionary influence on the development of<br />

Western music and the controversial nature of many of his views<br />

ensured the development of strong, even fanatical, support both<br />

for and against Wagner.<br />

Programme Notes<br />

3

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)<br />

Piano Concerto in A minor Op 54 (1841–1845)<br />

1 Allegro affettuoso<br />

2 Intermezzo grazioso –<br />

3 Allegro vivace<br />

Saleem Abboud Ashkar piano<br />

One of the most impressive features of Schumann’s only Piano<br />

Concerto is its remarkable organic unity. So many ideas in this richly<br />

imaginative work stem in one way or another from the lovely first<br />

movement melody (wind, then solo piano) that follows the concerto’s<br />

arresting opening. So it comes as quite a surprise to discover that<br />

the concerto was actually written in two separate instalments, and<br />

at two very different times in Schumann’s life. the first movement<br />

was originally written as a self-sufficient Fantasie for Piano and<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> in 1841 – the year that also saw the composition of the<br />

First <strong>Symphony</strong>, the original version of the Fourth, and the orchestral<br />

Overture, Scherzo and Finale. Schumann’s long-thwarted marriage<br />

to the brilliant concert pianist Clara Wieck the previous year had<br />

released a torrent of creativity: the first years of their life together<br />

saw the production of some of his finest pieces, often composed<br />

at breathtaking speed.<br />

then, in 1844, after Schumann and Clara had returned from a<br />

concert tour of Russia, Schumann experienced a crippling mental<br />

breakdown, followed by a terrible plunge into depression. At the end<br />

of the year he and Clara moved to Dresden with their two children,<br />

where gradually Schumann’s spirits began to recover. For a long<br />

time Schumann was unable to compose, but by the end of 1845<br />

he completed his <strong>Symphony</strong> No 2, a work which bears powerful<br />

witness to his struggles to regain health and stability. And before he<br />

started the symphony, Schumann added two more movements to<br />

the Fantasie, thus creating his Piano Concerto. How long the ideas for<br />

these two movements had been incubating in his mind is impossible<br />

to say, but it is certain that the act of putting them to paper was a<br />

major step forward on his road to psychological recovery. the result<br />

was one of Schumann’s most daring and romantically delightful<br />

works. It is easy to single out innovatory elements: the piano’s striking,<br />

downward-plunging opening gesture – after a single incisive chord<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

from the full orchestra – is unlike the beginning of any concerto<br />

before. It clearly left a strong impression on the Norwegian composer<br />

edvard Grieg, who began his famous Piano Concerto (also in A minor)<br />

with a strikingly similar gesture. And although Schumann’s first<br />

movement appears to be full of melodic ideas, most of these derive<br />

directly from the original wind-piano tune – so much so that the<br />

movement has been described as ’monothematic’ – also very unusual<br />

for an early 19th-century concerto.<br />

But it is the dream-like quality Schumann brings to this kind of<br />

intricate thematic development that is most original. the piano writing<br />

may be challenging, but the real challenge is to the player’s poetic<br />

imagination rather than his or her virtuosity. even the first movement’s<br />

solo cadenza is more like a meditation than a bravura display.<br />

In general the relationship between the piano and the orchestra<br />

is neither as one-sided nor as competitive as in most romantic<br />

concertos. tender intimacy is much more typical. A couple of years<br />

before he began the first movement, Schumann had written of his<br />

hope that a new kind of ’genius’ might soon emerge: one ’who will<br />

show us in a newer and more brilliant way how orchestra and piano<br />

may be combined, how the soloist, dominant at the keyboard, may<br />

unfold the wealth of his instrument and his art, while the orchestra,<br />

no longer a mere spectator, may interweave its manifold facets into<br />

the scene’. In the Piano Concerto he fulfilled his own prophecy.<br />

the chamber music-like intimacy continues through the gentle<br />

Intermezzo Schumann placed as the concerto’s second movement –<br />

and again the way in which one motif seems to unfold from another<br />

is achieved with great subtlety and ingenuity. Just before the end<br />

of the movement comes a wonderful inspiration. Clarinets and<br />

bassoons recall the seminal first phrase of the first movement’s<br />

original melody – first in the major key, then in the minor – while the<br />

piano adds magical liquid figurations (as though dreamily recalling the<br />

concerto’s arresting opening). then the finale launches suddenly into<br />

an exhilarating, seemingly unstoppable waltz momentum. It is hard<br />

to believe that the man who wrote this gloriously alive dance music<br />

was at the time emerging from chronic depression. the ending in<br />

particular sounds like an outpouring of the purest joy.

Robert Schumann<br />

Composer Profile<br />

the youngest son of a Saxon bookseller, Robert Schumann was<br />

encouraged by his father to study music. Soon after his tenth birthday<br />

in 1820, young Robert began taking piano lessons in his home town<br />

of Zwickau. Although Schumann enrolled as a law student at Leipzig<br />

University in 1828, music remained an overriding passion and he<br />

continued to study piano with Friedrich Wieck. the early death of<br />

his father and two of his three brothers influenced Schumann’s<br />

appreciation of the world’s suffering, intensified further by his<br />

readings of Romantic poets such as Novalis, Byron and Hölderlin<br />

and his own experiments as poet and playwright.<br />

Schumann composed a number of songs in his youth, but it was not<br />

until he fell in love with and became secretly engaged to the teenage<br />

Clara Wieck in September 1837 that he seriously began to exploit<br />

his song-writing gift. Besides welcoming the financial return that<br />

published lieder [songs] could deliver, Schumann was also able to<br />

preserve his intense feelings for Clara in the richly expressive medium<br />

of song. the personal nature of Schumann’s art even influenced his<br />

choice of certain themes, with the notes A – B – e – G – G enshrined<br />

as the theme of one set of piano variations in tribute to his friend<br />

Countess Meta von Abegg. Schumann also developed his skills as a<br />

composer of symphonies and concertos during his years in Leipzig.<br />

Four years after their marriage in September 1840, the Schumanns<br />

moved to Dresden where Robert completed his C major <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

In the early 1850s the composer’s health and mental state seriously<br />

declined, perhaps as a consequence of tertiary syphilis. In March<br />

1854 he decided to enter a sanatorium near Bonn, where he died<br />

two years later.<br />

Programme Note and Composer Profile © Stephen Johnson<br />

Stephen Johnson is author of Bruckner Remembered (Faber).<br />

He also contributes regularly to BBC Music Magazine, and broadcasts<br />

for BBC Radio 3 (Discovering Music), Radio 4 and the World Service.<br />

INteRvAL: 20 Minutes<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Season <strong>2011</strong>/12<br />

International Pianists<br />

Mitsuko Uchida<br />

Sun 4 & tue 6 Dec 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Beethoven<br />

Piano Concerto No 4<br />

6 Dec sponsored by Canon europe<br />

Recommended by Classic FM<br />

Sun 11 & tue 13 Dec 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Beethoven<br />

Piano Concerto No 5<br />

Nicolas Hodges<br />

Sun 15 Jan 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Thomas Adès<br />

In Seven Days for Piano &<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

tickets £10 to £35<br />

Box Office<br />

020 7638 8891 (bkg fee)<br />

lso.co.uk (reduced bkg fee)<br />

Nelson Freire<br />

tue 24 Jan 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Debussy<br />

Fantasy for Piano & <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

André Previn<br />

Mon 20 Feb 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Mozart, Previn &<br />

Mendelssohn Piano trios<br />

with Anne-Sophie Mutter and<br />

Daniel Müller-Schott<br />

Part of UBS Soundscapes<br />

Programme Notes<br />

5

Johannes Brahms (1833–97)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 4 in e minor Op 98 (1884–85)<br />

1 Allegro non troppo<br />

2 Andante moderato<br />

3 Allegro giocoso<br />

4 Allegro energico e passionato<br />

Brahms composed his last symphony during the summers of 1884<br />

and 1885, although as so often with his major works he had been<br />

turning over some of the ideas in his mind for many years. Instead<br />

of a premiere in vienna, where the first three symphonies had been<br />

introduced (in 1876, 77 and 83), he chose instead to entrust its first<br />

performance to the small orchestra at the Ducal court of Meiningen<br />

in Germany, where Hans von Bülow had been in charge since 1880<br />

and was soon to be succeeded by the young Richard Strauss. Brahms<br />

himself conducted the symphony’s premiere on 25 <strong>October</strong> 1885,<br />

then the orchestra took it on tour through Germany and Holland,<br />

with Brahms and von Bülow sharing the conducting.<br />

time has softened one aspect of this symphony. We have become<br />

used to music that is so much harsher on the ears that we are at<br />

first struck by its richness of sound, so warm and seductive, and<br />

by its passionate lyricism. It requires an effort of the imagination to<br />

appreciate the impression of austerity and even grittiness that it made<br />

120 years ago. even some of Brahms’ closest friends were dismayed.<br />

His biographer Max Kalbeck, after hearing a performance on two<br />

pianos, advised the composer to publish the finale separately and<br />

scrap the third movement altogether. elisabeth von Herzogenberg<br />

wrote, ‘It seems to me as though this particular work has been too<br />

carefully designed for inspection through a microscope, as though<br />

its charms were not open to just any music-lover, as though it<br />

were a tiny world for the clever and the initiated’. A more balanced<br />

appreciation came from the violinist Joseph Joachim, when in 1886<br />

he told the composer, ‘the thrilling tension of the whole work, the<br />

concentration of feeling, the wonderfully intertwined development<br />

of motifs, even more than the richness and beauty of individual<br />

details, appeal to me so much that I almost think the e minor is<br />

my favourite of the four symphonies’.<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

At times it seems that the essence of Brahms is a constant struggle<br />

between tragic stoicism and romantic lyricism, and the Fourth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> is the most dramatic expression of this conflict. Brahms’<br />

mastery of classical forms creates an internal drama, his controlling<br />

intellect leading the listener from bar to bar with an accumulation<br />

of detail and incident that eventually build up to what is perhaps the<br />

most complete picture we have of the composer’s emotional world.<br />

the first movement’s theme, quietly spreading wider and wider, is in<br />

a continuous state of development from the very beginning, and the<br />

falling thirds which comprise it appear throughout the symphony in<br />

one form or another. the motivic web is in fact more dense than in<br />

the previous symphonies, though since the themes are so distinct<br />

and characterful these cross-references are rarely heard on the<br />

surface, but act as a current running through the entire score at a<br />

subliminal level. the horn calls and dark modal colouring of the slow<br />

movement are essential images of German Romanticism: to Richard<br />

Strauss the movement suggested ‘a funeral procession moving in<br />

silence across moonlit heights’. the third movement (the last to be<br />

composed, and therefore well calculated for its overall effect in the<br />

symphony) is a blaze of major-key energy, dispelling the shadows of<br />

the Andante and setting up high expectations for a finale that will<br />

crown the different areas that the symphony has so far explored.<br />

the first three movements all follow some form of sonata structure.<br />

For the finale, though, Brahms drew on the ancient form of the<br />

passacaglia, or variations on a repeated bass. As early as February<br />

1869 he had written of his fondness for this technique: ‘With a theme<br />

and variations it is really only the bass line which is important to me …<br />

If I use just the melody as the basis for variations, I find it hard to<br />

go beyond the witty or charming, though I may make something<br />

pretty, perhaps developing on a lovely idea. Over a given bass line,<br />

however, I can become truly innovative: I can create new melodies’.<br />

the passacaglia theme of the Fourth <strong>Symphony</strong> is derived (with<br />

alterations) from the final chorus of J S Bach’s Cantata BWv 150,<br />

‘Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich’ (For thee, O Lord, I long), and Brahms<br />

must also have had in mind the extraordinary Chaconne which ends<br />

Bach’s Partita for Solo violin in D minor, which he had arranged for

piano left-hand in 1877. the use of such a repeating pattern means<br />

that there is none of the modulation from key to key which we<br />

expect in a symphonic finale. Instead, Brahms created a scheme<br />

of 32 variations which are firmly anchored in e minor, but display<br />

such ingenuity and variety that there is a sense of headlong forward<br />

movement right up to the final bars.<br />

Programme Note © Andrew Huth<br />

Andrew Huth is a musician, writer and translator who writes<br />

extensively on French, Russian and Eastern European music.<br />

Music’s better shared!<br />

there’s never been a better time to bring all your friends to an<br />

LSO concert. Groups of 10+ receive a 20% discount on all tickets,<br />

plus a host of additional benefits. Call the dedicated Group Booking<br />

Line on 020 7382 7211 visit lso.co.uk/groups or email<br />

groups@barbican.org.uk<br />

On <strong>Sunday</strong> <strong>30</strong> <strong>October</strong> we welcome the Enfield National Trust<br />

Association, Gerrards Cross Community Association,<br />

Kelvedon Hatch Village Society, Ruislip WCA Music Society<br />

and Witham Choral Society.<br />

Johannes Brahms<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Johannes Brahms was born in Hamburg, the son of an impecunious<br />

musician; his mother later opened a haberdashery business to help<br />

lift the family out of poverty. Showing early musical promise he<br />

became a pupil of the distinguished local pianist and composer<br />

eduard Marxsen and supplemented his parents’ meagre income<br />

by playing in the bars and brothels of Hamburg’s infamous red-light<br />

district. In 1853 Brahms presented himself to Robert Schumann in<br />

Düsseldorf, winning unqualified approval from the older composer.<br />

Brahms fell in love with Schumann’s wife, Clara, supporting her after<br />

her husband’s illness and death. the relationship did not develop as<br />

Brahms wished, and he returned to Hamburg; their close friendship,<br />

however, survived. In 1862 Brahms moved to vienna where he found<br />

fame as a conductor, pianist and composer. the Leipzig premiere<br />

of his German Requiem in 1869 proved a triumph, with subsequent<br />

performances establishing Brahms as one of the emerging German<br />

nation’s foremost composers. Following the long-delayed completion<br />

of his First <strong>Symphony</strong> in 1876, he composed in quick succession the<br />

majestic violin Concerto, the two piano Rhapsodies, Op 79, the First<br />

violin Sonata in G major and the Second <strong>Symphony</strong>. His subsequent<br />

association with the much-admired court orchestra in Meiningen<br />

allowed him freedom to experiment and de v el op new ideas, the<br />

relationship crowned by the Fourth <strong>Symphony</strong> of 1884.<br />

In his final years, Brahms composed a series of profound works<br />

for the clarinettist Richard Mühlfeld, and explored matters of life<br />

and death in his Four Serious Songs. He died at his modest lodgings<br />

in vienna in 1897, receiving a hero’s funeral at the city’s central<br />

cemetery three days later.<br />

Profile © Andrew Stewart<br />

Andrew Stewart is a freelance music journalist and writer.<br />

He is the author of The LSO at 90, and contributes to a wide<br />

variety of specialist classical music publications.<br />

Programme Notes<br />

7

Nikolaj Znaider<br />

Conductor<br />

‘A good conductor,<br />

and time might well turn<br />

him into a great one’<br />

the Guardian, March 2010<br />

Nikolaj Znaider is not only celebrated as one<br />

of the foremost violinists of today, but is fast<br />

becoming one of the most versatile artists of<br />

his generation uniting his talents as soloist,<br />

conductor and chamber musician.<br />

this season Nikolaj Znaider was invited by<br />

valery Gergiev to become Principal Guest<br />

Conductor of the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> in<br />

St Petersburg where he will conduct a<br />

production of The Marriage of Figaro and<br />

a number of symphonic concerts. As well<br />

as the LSO, he has been invited to guest<br />

conduct the Royal Concertgebouw <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Munich Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic,<br />

LA Philharmonic, Pittsburgh <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France,<br />

WDR Köln and already has re-invitations to<br />

conduct the Dresden Staatskapelle, Russian<br />

National <strong>Orchestra</strong>, the Hallé, Swedish<br />

Radio <strong>Orchestra</strong> and Gothenburg <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

the <strong>2011</strong>/12 season sees Znaider as Artistin-Residence<br />

with the Dresden Staatskapelle<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>. He will conduct them in concert,<br />

perform violin concertos with Sir Colin Davis<br />

and play a recital.<br />

As a soloist, Znaider is regularly invited to<br />

work with the world’s leading orchestras<br />

and conductors such as Daniel Barenboim,<br />

Sir Colin Davis, valery Gergiev, Lorin Maazel,<br />

Zubin Mehta, Christian thielemann, Mariss<br />

Jansons, Charles Dutoit, Christoph von<br />

Dohnányi, Ivan Fischer and Gustavo Dudamel.<br />

In recital and as a chamber musician he<br />

appears at all the major concert halls. In<br />

the 2008/9 season the LSO presented an<br />

Artist Portrait of Znaider and in the 2012/13<br />

season he will present a Carte Blanche at<br />

the Musikverein in vienna.<br />

An exclusive RCA Red Seal recording<br />

artist, Znaider’s most recent addition to his<br />

discography is the elgar violin Concerto with<br />

Sir Colin Davis and the Dresden Staatskapelle.<br />

His award-winning recordings of the Brahms<br />

and Korngold violin Concertos with the<br />

vienna Philharmonic and valery Gergiev, the<br />

Beethoven and Mendelssohn Concertos with<br />

Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic<br />

and Prokofiev’s Second and Glazunov violin<br />

Concertos with Mariss Jansons and the<br />

Bayerische Rundfunk have been greeted<br />

with great critical acclaim, as was his release<br />

of the complete works for violin and piano<br />

of Johannes Brahms with Yefim Bronfman.<br />

For eMI Classics he has recorded the Mozart<br />

Piano trios with Daniel Barenboim and<br />

the Nielsen and Bruch Concertos with the<br />

<strong>London</strong> Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

Znaider is passionate about the education<br />

of musical talent and was for ten years<br />

Founder and Artistic Director of the Nordic<br />

Music Academy, an annual summer school<br />

whose vision it was to create conscious<br />

and focused musical development based<br />

on quality and commitment.<br />

8 The Artists Nikolaj Znaider © George Lange

Saleem Abboud Ashkar<br />

Piano<br />

‘Ashkar’s rubato lines almost<br />

melted on the ears.’<br />

New Zealand Herald, March <strong>2011</strong><br />

Saleem Abboud Ashkar made his New York<br />

Carnegie Hall debut at the age of 22 and<br />

has since worked with many of the world’s<br />

leading orchestras including the vienna<br />

Philharmonic, Israel Philharmonic, Chicago<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>, La Scala Philharmonic, Leipzig<br />

Gewandhaus, Deutsche <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Berlin, Radio <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> Berlin,<br />

Maggio Musicale, New Zealand <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, Bergen Philharmonic, Mariinsky<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and the <strong>Orchestra</strong> of the Royal<br />

Danish theatre.<br />

He performs regularly with conductors<br />

such as Zubin Mehta, Daniel Barenboim,<br />

Riccardo Muti, Lawrence Foster, Bertrand<br />

de Billy, Philippe Jordan and Ludovic Morlot,<br />

and following a highly successful debut with<br />

Christoph eschenbach and the NDR Hamburg<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, with whom he was immediately<br />

re-invited to work, eschenbach invited Ashkar<br />

Saleem Abboud Ashkar © Monika Rittershaus<br />

to play the Schumann Piano Concerto with<br />

the Düsseldorf <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> in the<br />

Schumann Birthday Concert in June 2010.<br />

Ashkar has toured extensively with Riccardo<br />

Chailly and the Leipzig Gewandhaus<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> performing Mendelssohn’s First<br />

Piano Concerto, including appearances at<br />

the BBC Proms and Lucerne Festivals, in a<br />

tour celebrating the bicentennial anniversary<br />

of the composer’s birth, and Chailly has<br />

re-invited Saleem for concerts and to record<br />

with him for Decca in the 2012/13 season.<br />

Appearances in this and future seasons<br />

include invitations to make debuts with the<br />

Royal Concertgebouw <strong>Orchestra</strong> and the LSO<br />

playing concerts in <strong>London</strong> and Bucharest,<br />

WDR Köln, the Konzerthaus <strong>Orchestra</strong> Berlin,<br />

Danish National <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and National<br />

Arts Centre <strong>Orchestra</strong> Ottawa at the invitation<br />

of Pinchas Zukerman.<br />

A dedicated recitalist and chamber<br />

musician, Ashkar appears regularly in series<br />

at venues such as the Concertgebouw,<br />

Mozarteum Salzburg, Musikverein vienna,<br />

Conservatorio Guiseppe verdi in Milan and<br />

at festivals including Salzburg with the vienna<br />

Philharmonic, the BBC Proms with Leipzig<br />

Gewandhaus <strong>Orchestra</strong>, at tivoli with the<br />

Israel Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta, in<br />

Lucerne, Ravinia, Risor, Menton and the<br />

Ruhr Klavier Festival, collaborating with<br />

artists including Daniel Barenboim,<br />

Nikolaj Znaider and Waltraud Meier.<br />

BBC Radio 3 Lunchtime Concerts<br />

Thursdays at 1pm, LSO St Luke’s<br />

Beethoven Piano Sonatas<br />

A complete retrospective<br />

Thu 3 Nov 1pm<br />

Nicholas Angelich<br />

Sonatas Op 2 No 2, Op 31 No 1<br />

Thu 10 & 17 Nov 1pm<br />

elisabeth Leonskaja<br />

Sonatas Op 13 (‘Pathétique’),<br />

Op 14 No 1, Op 110, Op 49 No 2,<br />

Op 109, Op 111<br />

Thu 24 Nov 1pm<br />

Barry Douglas<br />

Sonatas Op 79,<br />

Op 106 (‘Hammerklavier’)<br />

Tickets £10<br />

lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts<br />

020 7638 8891<br />

The Artists<br />

9

Nikolaj Znaider<br />

on conducting the LSO<br />

‘It is very much about<br />

all of us on stage sharing<br />

our passion for the music<br />

we are performing.’<br />

Nikolaj Znaider is not only celebrated as one of the<br />

foremost violinists of today, but is fast becoming<br />

one of the most versatile artists of his generation<br />

uniting his talents as soloist, chamber musician<br />

and most recently, as a conductor.<br />

Just before the <strong>London</strong> season started Nikolaj Znaider<br />

made his conducting debut with the LSO in Bucharest<br />

and preceding his Barbican concert with the LSO on<br />

<strong>30</strong> <strong>October</strong>, Isla Jeffrey caught up with Nikolaj to<br />

ask him about his experience as a conductor and<br />

plans for the future.<br />

10 Nikolaj Znaider Interview<br />

Was there any particular moment in your life or a particular<br />

piece of music that made you want to start conducting?<br />

there were several but the first instance was when I was studying<br />

the Beethoven symphonies, closely followed by attending a week’s<br />

rehearsals for The Marriage of Figaro.<br />

Do you have a favourite Beethoven symphony?<br />

No! I don’t believe in favourite anything. I wouldn’t want to be<br />

without any of them. Like people, good friends, you wouldn’t want<br />

to miss any one of them.<br />

What did your first professional conducting experience<br />

feel like?<br />

terrifying. Nothing can ever prepare you properly for it. You think you<br />

can look at it from afar and predict how it’s all going to go but you just<br />

can’t. As a violin soloist, I have been standing next to conductors –<br />

very close to them on the stage – for many years, and yet the feeling<br />

that your physical movements can impact in a very real way what<br />

comes out is a totally overwhelming experience. I remember after<br />

my first rehearsal being so exhausted, so overwhelmed that I went<br />

straight to bed. It must have been only 2pm and I didn’t get out of bed<br />

again until the rehearsal the next day!

Has your experience as a violin player influenced your<br />

conducting style or understanding of conducting in any way?<br />

I think it has to have. I would say that it has influenced the way I<br />

conduct. the ideal sound that I hear in my head, and that I try to<br />

recreate as a violinist, is the same in principle as when I hear my ideal<br />

orchestral sound. this way of listening has very much informed the<br />

way I conduct, and the way I listen to the orchestra’s sound.<br />

What would you say is the biggest performing difference<br />

between being a soloist and a conductor?<br />

As a violinist you are directly responsible for the sound, and as a<br />

conductor, indirectly responsible. Aside from that, and this is really<br />

the miraculous discovery I made, there is no difference. It is the<br />

same thing. It is all about sharing the delight in music with others,<br />

being aware of what the musicians with you on stage are doing;<br />

interacting with them and reacting to them. Yes, the function is<br />

different but it’s really all the same thing.<br />

You have described yourself as having ‘Mahleria’.<br />

Are there any other great composers or works you<br />

are looking forward to working on?<br />

Anything Mozart, anything Beethoven, anything that when you return<br />

to it remains our Holy Grail, the things that we can only hope to ever<br />

get near. there’s opera, and I’m looking forward to getting into that.<br />

Something coming up for me in the very near future are the Stravinsky<br />

ballets; they really fascinate me and I haven’t been able to do<br />

anything like that before. In the same way that Mahler didn’t write any<br />

violin concertos, so Mahler was a new performing experience for me,<br />

Stravinsky is something completely different that I can’t wait to sink<br />

my teeth into. Stravinsky did write a violin concerto but it was much<br />

later on and in a completely different style to the early ballets.<br />

Is there a conductor who has influenced or inspired<br />

you the most?<br />

A lot. I really think there is so much to learn if one just opens one’s<br />

eyes. Daniel Barenboim was a huge influence on helping me to think<br />

like a conductor and of course, the person who has meant the most<br />

to me on so many levels, humanly and musically is Sir Colin Davis.<br />

He means so much to me in so many ways. One of the things which<br />

makes my relationship with the LSO special is that we share that great<br />

relationship with Colin.<br />

What are you most looking forward to about your concert<br />

with the LSO on <strong>30</strong> <strong>October</strong>?<br />

Now that I have conducted them already, what I know about them<br />

is that they are all such generous musicians and a music-making<br />

experience with them is truly about love. It is very much about all<br />

of us on stage sharing our passion for the music we are performing.<br />

this <strong>Orchestra</strong> has so much to give, and that is what I am looking<br />

forward to most about being on stage with them.<br />

Coming up with Nikolaj Znaider<br />

Tue 8 May 7.<strong>30</strong>pm<br />

Bartók Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste<br />

Bartók violin Concerto No 2<br />

Szymanowski <strong>Symphony</strong> No 3 (‘Song of the Night’)<br />

with Pierre Boulez conductor<br />

Tickets from £10<br />

Box Office 020 7638 8891 (bkg fee)<br />

lso.co.uk (reduced bkg fee)<br />

Nikolaj Znaider Interview<br />

11

On stage<br />

First Violins<br />

Carmine Lauri Leader<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Sylvain vasseur<br />

Rhys Watkins<br />

David Worswick<br />

Daniel Bhattacharya<br />

Sophie Mather<br />

Hilary Jane Parker<br />

Alina Petrenko<br />

erzsebet Racz<br />

Helena Smart<br />

Second Violins<br />

evgeny Grach<br />

thomas Norris<br />

Miya vaisanen<br />

David Ballesteros<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Raja Halder<br />

William Melvin<br />

Katerina Mitchell<br />

Stephen Rowlinson<br />

Julia Rumley<br />

Samantha Wickramasinghe<br />

12 The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Violas<br />

edward vanderspar<br />

Malcolm Johnston<br />

Regina Beukes<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Anna Green<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert turner<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Melanie Martin<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Fiona Opie<br />

Alistair Scahill<br />

Cellos<br />

David Cohen<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Mary Bergin<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Amanda truelove<br />

Delphine Biron<br />

Judit Berendschot<br />

Penny Driver<br />

Judith Herbert<br />

Double Basses<br />

Anthony Alcock<br />

Colin Paris<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Matthew Gibson<br />

thomas Goodman<br />

David Gordon<br />

Rachel Meerloo<br />

Simo vaisanen<br />

Flutes<br />

Gareth Davies<br />

Julian Sperry<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Steven Hudson<br />

Michael O’Donnell<br />

Clainets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bassoons<br />

Daniel Jemison<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Contra-bassoon<br />

Dominic Morgan<br />

Horns<br />

timothy Jones<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Antonio Geremia Iezzi<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philip Cobb<br />

Christopher Deacon<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Robin totterdell<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

Katy Jones<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Tuba<br />

Patrick Harrild<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

David Jackson<br />

Harp<br />

Karen vaughan<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String experience Scheme<br />

enables young string players<br />

at the start of their careers<br />

to gain work experience<br />

by playing in rehearsals<br />

and concerts with the LSO.<br />

20 students per year from<br />

across the <strong>London</strong> music<br />

conservatoires are selected<br />

to participate. the musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

tonight, Aki Sawa (First violin),<br />

Stephanie edmundson (viola),<br />

Mark Lindley (Cello) all took<br />

part in rehearsals and will be<br />

performing on stage in Brahms<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 4.<br />

the Scheme is supported by:<br />

the Barbers’ Company<br />

the Carpenters’ Company<br />

Charles and Pascale Clark<br />

the Ironmongers’ Company<br />

Robert and Margaret Lefever<br />

LSO Friends<br />

Musicians Benevolent Fund<br />

the Polonsky Foundation<br />

Editor<br />

edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Photography<br />

Mark Harrison, Kevin Leighton,<br />

Bill Robinson, Alberto venzago,<br />

Nigel Wilkinson<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450